I made arrangements to watch a new film about the Holocaust that sounded interesting, Three Minutes—A Lengthening. But then, it operated on me like a surgical procedure: it brought unconscious deep fears to the surface that I didn’t even know I had. It upset me so much that two baby bull snakes and two gigantic Wolf spiders came into the house that night, as if my fear had reverberated down to awaken them in their nests and touch their webs, summoning them up from the depths to come for a visit.

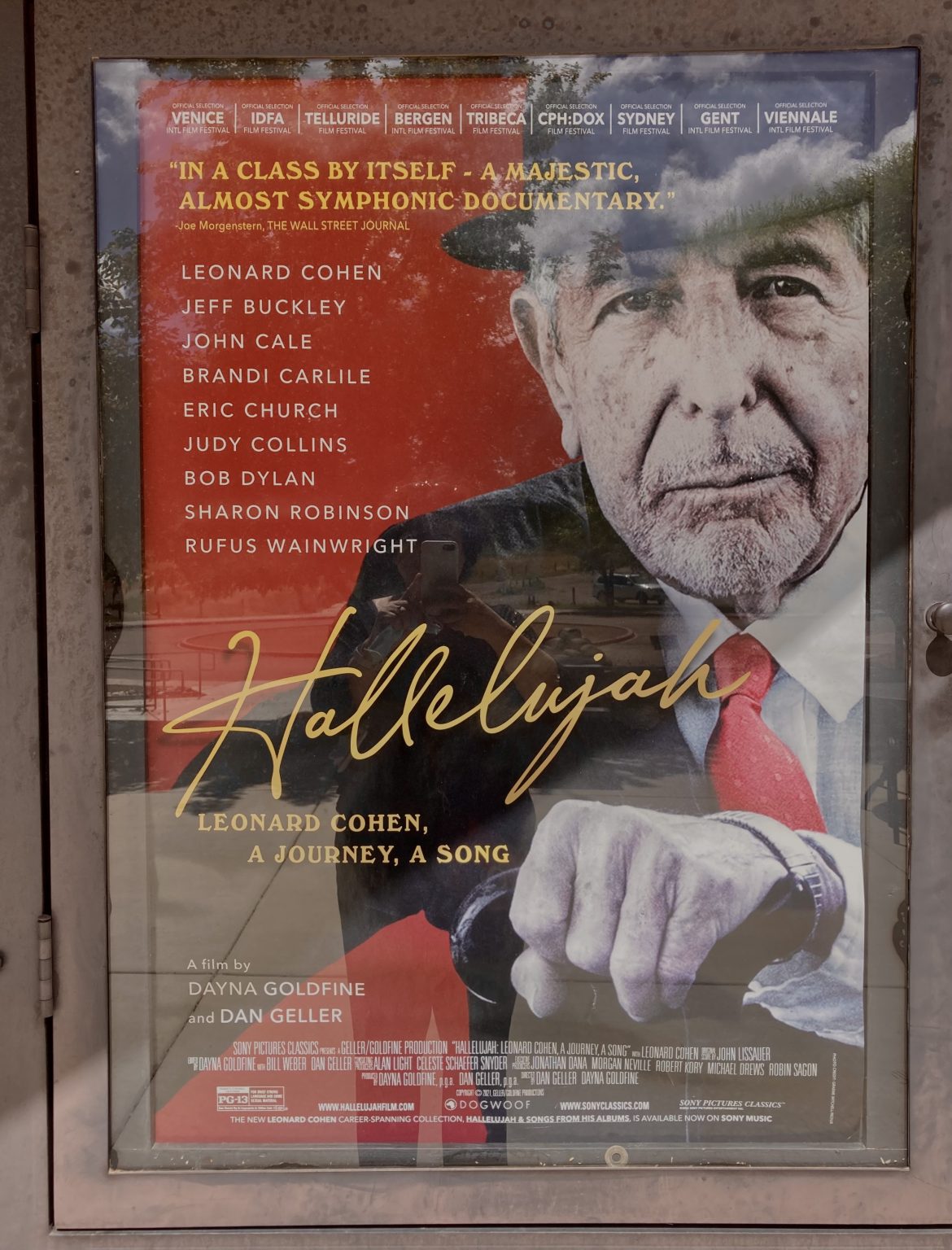

So then I didn’t think I could write about that film and decided instead to view Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song. Currently in limited release in theaters, it will be available for sale on DVD on Oct. 11th.

This film Hallelujah reconnected me to myself. It acted like a key that opened new doors of creativity. But somehow first I had to be broken.

The painful film that I didn’t want to write about, Three Minutes, brings an awareness of the Holocaust without ever actually showing what happened—the film footage was shot just on the edge of what was about to happen.

In 1938 Kodak came out with an amateur version of their 16-millimeter Cine Kodak film camera. Spring-loaded, you popped in a cassette, black and white or color, cranked it up, and it would run for a few minutes. That year, David Kurtz, who had left Poland in the 1890’s, having done well in America, decided to make a grand tour of Europe, and on a side trip, revisited his ancestral village of Nasielsk. He shot 3 minutes of film there.

His grandson Glenn Kurtz went on a hunt for the film 70 years later, and found it, moldering away in his parents’ closet, in 2008, just before it would be lost forever. The old film’s base was dissolving, but because someone had transferred part of it onto VHS tape in the 1980’s, he could see what it was. He sent it to be restored by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, and published a book about its significance, Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film, published byFarrar, Strauss and Giroux in 2014, and heralded as one of the best books of the year by the New Yorker and others. This year, Dutch filmmaker Bianca Stigter, together with her British producer husband Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), released a documentary film based on Kurtz’s book to international acclaim. The film has a curious intensity—it contains no talking heads, just a deep examination of the moments in the footage and each of the faces it documented, narrated by a woman’s voice.

In August of 1938, crowds of happy children mugged for the novel movie camera. They excitedly ran down the street to remain in its eye as the man panned along the houses. Never in their wildest nightmares did they dream of what was to come. In September 1939, Germany swept over Poland and took away and killed almost all the Jewish people living there, the children, the mothers and fathers, in every little town and village. The entire Jewish population of Nasielsk was rounded up, held in the synagogue for three days, and then taken away and deported, mostly to Treblinka.

As I watched this film in a sunny late summer afternoon, I spotted a young girl who stood front and center for the camera in a crowd. I recognized myself, my features, in hers. In that way, in that moment I connected with the reality of what had happened. I was swept into the horror of what was to come, thrown into a time machine eight decades back.

Later, I had a feeling—I looked on a map. The town, Nasielsk, Poland, where David Kurtz was born in about 1880, was 35 miles northeast of Warsaw. Another 35 miles northeast from there, practically the next town over, Raciaz, is where my grandmother was born in the early 1880’s. She left Poland with my great-grandparents when she was five. My mother remembered her writing letters in Yiddish for my great-grandmother to a relative back in Poland. After 1939 they heard nothing.

A girl flips her bobbed hair back and forth, sitting at a window looking out. The film replays this. Then, a blurred screen. A voice narrates what happened then in Nasielsk when the Germans came.

The record of what happened was because Emanuel Ringelblum, a Jewish historian, organized teams in the Warsaw ghetto who wrote down eye-witness testimonies from Jews as they streamed in from the countryside. These oral histories were buried in boxes and three large milk cans in the cellars of buildings. They also contained the only eye-witness account, by an escapee from the death camp of Chelmno in 1942, about the mass extermination in gas vans, which was smuggled out that year to England. Ringelblum and his family later escaped, but were captured and shot in 1944. After the war, boxes and two of the milk cans were found.

Eventually, Kurtz would locate 7 survivors from Nasielsk. They had been children in the film. Today, viewers feel a sense of immediacy, that presence that home movies capture. One survivor said that viewing the film gave him back his childhood. The narrator suggests that for the survivors, the images we are watching are just a token of a whole world they had lost.

Hallelujah

The documentary film, “Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song,” directed by Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine, traces the evolution of his most famous song, “Hallelujah,” through focusing on Cohen as a seeker, a spiritual searcher. At one level, the essence of Judaism is in asking questions.

Watching this film I found myself mysteriously reconnecting to a part of myself that also had been buried a long time. The patina of life’s mundanity was replaced with the deep chords of the soul’s search. After seeing it, I felt good in my heart. And that night, attending a life-drawing class, I drew like I never had been able to draw before— the strokes emanated from inside of me, sweeping through my arm into my fist that held a bit of charcoal against the paper.

Judaism teaches about the paradoxical nature of things – the ineffable, the unknowable, the name of God that cannot be named – and yet, here we are, commanded to sing His praises. And still yet, “Hallelujah” sets you up to go one way, then throws you another. In that very experience, Cohen gives a taste of that paradoxical, contradictory, nature of things. The song begins:

I’ve heard there was a secret chord

that David played to please the Lord

but you don’t really care for music, do you?

It goes like this: the fourth, the fifth

the minor fall, the major lift;

the baffled king composing “Hallelujah.”

About songwriting, Cohen is shown saying, “It is, it is a gift—of course you have to keep your tools, keep your skill in a condition of operation but the real song, where that comes from, no one knows, that is grace, that is a gift, and that is, that is not yours. If I knew where songs came from I would go there more often.”

The film then cuts to his rabbi, Rabbi Finley, who says, “There’s something called the Bat Kol, which in the Torah is the feminine voice of God that extends into people. The Bat Kol arrives. And if you’re in her service, you write down what she says. And then she goes away. So the baffled king is ‘I just wrote this secret chord, I don’t know how I got it, but what I think I did is, I made myself open to the Bat Kol.’”

It took Cohen four years or more to write “Hallelujah,” and he reportedly wrote somewhere between 80 and 180 verses. At one point he found himself banging his head on the floor of his hotel room, despairing of ever finishing it.

Finally, he selected four verses, with the refrain Hallelujah repeated four times between each verse, and recorded it in 1985 on the album Various Positions. It then came as a great shock when the new head of Columbia Records rejected the album and refused to release it.

The film follows the song’s slow torturous rise from this obscurity—Bob Dylan recognized its brilliance and would sing verses of it in concert; John Cale, of Velvet Underground fame, asked Cohen to share more of the verses with him, which he performed in a solo concert in 1991. Then, in 1994, Jeff Buckley recorded it on his album “Grace,” the version that ultimately brought “Hallelujah” into national prominence.

Cohen was a spiritual seeker, but he was also tormented by terrible depressions, which he treated by drinking too much. He retreated to a Zen monastery outside Los Angeles for five years, but apparently, he and the Roshi would drink whiskey at night together there, so it was only later when he went to India and learned another form of meditation there that he finally found respite.

Cohen draws holiness into the world, into the act of love. And this unusual and rare humanity is what draws people to him, to this song, as a safe harbor, a place where we can find ourselves, in our own struggles. He reveals his struggle as an artist—to despair, to fail, to persevere, to keep going. A later verse goes like this:

Now maybe there’s a God above

But all I ever learned from love

is how to shoot at someone who outdrew you.

And it’s no complaint you hear tonight,

and it’s not some pilgrim who’s seen the light

It’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah.

Cohen rarely explained his work. He shared this: ”You look around and you see a world that is impenetrable; that cannot be made sense of. You either raise your fists, or you say ‘Hallelujah.’ I try to do both.”

After seeing the film there were certain things I wanted to learn about Leonard Cohen’s heritage: He was born in Montreal on September 21, 1934. His paternal grandfather came from the city of Suwalki in northeastern Poland in the 1870s; his mother was born in Lithuania. His family was very successful in the clothing business in Montreal. They liked to wear suits.

Here are some other things I learned along the way: Cohen’s parents gave him the Hebrew name Eliezer, meaning, God helps. He was brought up Orthodox, and with the idea that he was a direct descendant of Aaron, the first High Priest. At times throughout his life, he saw himself as a messianic figure, infusing spirituality in the masses. The film shows footage of his concert in Tel Aviv on September 29, 2009, when he gave the Priestly Blessing to the thousands gathered at Ramat Gan Stadium.

I wondered if he ever performed in Poland. He did. He performed in Poland, in 1985. Everyone there wanted him to say something about Solidarity founder Lech Walesa and the political turmoil going on at that time. Before singing Who by Fire, he said to the audience, “When I was a child and I went to synagogue every Saturday morning… And once, in this country, there were thousands of synagogues and thousands of Jewish communities which were wiped out in a few months. In the synagogue which I attended there was a prayer for the government.[…] I sing for everyone. My song has no flag, my song has no party. And I say the prayer, that we said in our synagogue, I say it for the leader of your union and the leader of your party. ‘May the Lord put a spirit, a wisdom and understanding into the hearts of your leaders and into the hearts of all their councilors.’”

I think this approach is helpful. It is forward-looking. It reflects Jewish values. To pray that all will be spiritually guided by wisdom.