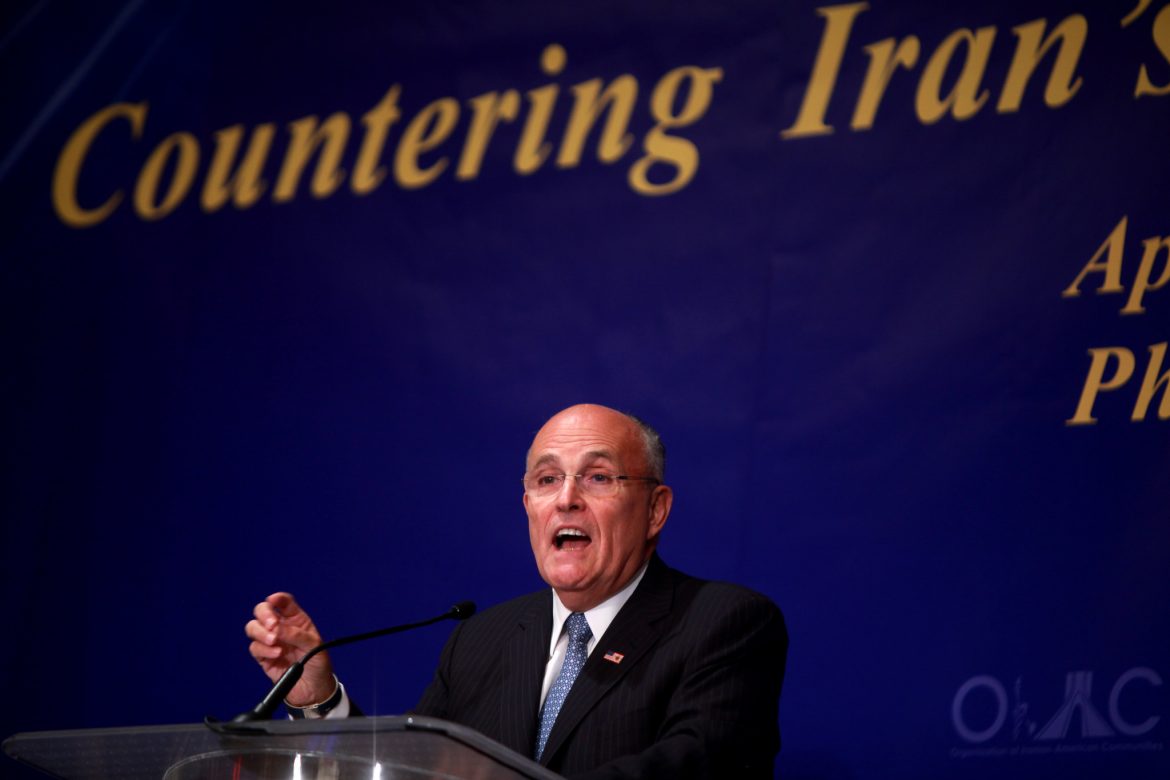

Editor’s note: In November, 2016, when President-elect Trump considered appointing Rudy Giuliani Secretary of State or Attorney General, Jim Sleeper wrote an essay for Foreign Policy magazine warning against giving him any national power or influence. Prescient then, the essay, slightly updated, is even more insightful now.

As Rudy Giuliani’s presidential campaign went from bad to worse in the 2008 Republican primaries, he must have been stung by Joe Biden’s observation then that every one of his sentences “contains a verb, a noun, and 9/11.” Now Rudy’s frantic efforts to discredit Biden’s candidacy are stinging his credibility even more as Donald Trump’s third big lawyer/fixer after Roy Cohn and Michael Cohen.

Having observed and written about Trump’s and Giuliani’s New York from the mid-1980s through Giuliani’s first term as mayor, I have something to say about how his career – as a prosecutor, mayor, operatic “hero” of 9/11, and, then, as a “consultant” of dubious repute – led him to find a fellow-fallen soul mate in Trump. Giuliani’s mind and career tell us as much as the impeachment inquiries are likely to do about why Trump’s presidency is so perverse. It has something to do with how and why extreme characters like Giuliani and Trump rise when millions of people are feeling stressed and dispossessed.

It’s been noted often enough that Giuliani underwent an evolution – or devolution — from the commanding, often brilliantly competent mayor of a great city on 9/11 to the terror-obsessed Rudy of 2008, and then to the crooked Rudy who enriched himself consulting for nations whose weapons purchases from the United States he hoped to oversee as Trump’s secretary of state. Observers haven’t been wholly wrong to assume that 9/11 deranged him: If you had gone through what he did, including attending hundreds of first responders’ funerals and hugging thousands of devastated survivors, afterward, you, too, would be struggling with a strain of post-traumatic stress disorder.

But the fuller truth is that Rudy has been struggling with something like PTSD since long before 9/11 triggered a chronic inability to control it. 9/11 simply unveiled, once and for all, demons that had always motivated his public life and fueled his talents. These psychological deficiencies bear a pretty close resemblance to Trump’s own. They also ought to be disqualifying for leaders of a democracy.

The tails of those demons weren’t readily apparent in Rudy at the start of his public career, when he enjoyed a reputation for being commanding and competent. The late, great muckrakers Jack Newfield and Wayne Barrett thought and wrote highly about him as U.S. Attorney during the late 1980s. Even during the 1993 New York mayoral race, in which he defeated David Dinkins, the city’s first African-American mayor, I tried harder than any other columnist I know of to convince my left-liberal friends and everyone else that Giuliani would probably win. To tell the whole truth, I also thought that he probably should win. New York “liberal’ Democrats’ corruption, sell-outs, and follies of New York Democrats back then had been told well enough by Newfield and Barrett in City for Sale.

In the Daily News, the New Republic, and on cable and network TV, I insisted it had come to this because racial “Rainbow” and welfare-state politics were imploding nationwide, not only thanks to racists, Ronald Reagan, or robber barons. One didn’t need to share all of Giuliani’s “colorblind,” law-and-order,” and free-market presumptions to want big shifts in liberal Democratic paradigms and to see that some of those shifts would require a political battering ram, not a scalpel.

I spent a lot of time with Giuliani during the 1993 campaign and his first year in City Hall. While I criticized him sharply when I thought he was overreaching, I defended much of his record to the end of his tenure — and still would. He forced New York, that great capital of “root cause” explanations for every social problem, to get real about remedies that work, at least for now, in the world as we know it. Giuliani’s successes ranged well beyond the city’s vaunted drop in crime. He also managed to facilitate housing, entrepreneurial, and employment gains for people whose loudest-mouthed advocates called him a racist reactionary. James Chapin, the late democratic-socialist savant, considered Giuliani a “progressive conservative” like Teddy Roosevelt, who’d been New York City’s police commissioner before becoming vice president and president.

Yet it became obvious to me pretty early on that Rudy wouldn’t be able to carry his methods and motives to any national political office or effort of consequence without damaging the country. The first reason was his ever-more-insistent disrespect for the established constraints of political institutions: A man who fought the inherent limits of his mayoral office as fanatically as Giuliani would construe national and federal prerogatives so broadly that he’d make George W. Bush’s notions of “unitary” executive power seem soft.

Even in the 1980s, as an assistant attorney general in the Reagan Justice Department and then as U.S. attorney in New York, Giuliani was imperious and overreaching. He was known for dramatically “perp-walking” Wall Streeters out of their offices even when he didn’t have cases compelling enough to ultimately convict them. In one failed prosecution, he forced the troubled daughter of a state judge, Hortense Gabel, to testify in a corruption trial in which her own mother was charged. The jury was so put off by Giuliani’s tactics that it acquitted all concerned.

At least, as U.S. Attorney, Giuliani served at the pleasure of the president and had to defer to federal judges. Had he ever become President, though as he hoped to do in 2008, or attorney general, as some say he hoped to do after Trump’s election, before that post was given to Jeff Sessions, U.S. Attorneys would have served at his pleasure and he’d have helped pick the judges to whom prosecutors defer. Even as any other kind of Trump cabinet member or close advisor, he’ll have Trump’s ear and very possibly too much influence over a broad range of protocols and picks.

The second and greater problem with Giuliani is his grandiosity, his need to always feel he has come out on top, even if it is in the role of bully. (Sound familiar?) As mayor, Giuliani fielded his closest aides like a fast, sometimes brutal hockey team, micromanaging and bludgeoning city agencies and even agencies that weren’t his, like the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and Board of Education. Some of those agencies deserved the Rudy treatment richly enough to make his bravado thrilling to many of us, though he wasn’t above pandering shamelessly to some Hispanics, orthodox and neoconservative Jews, and other favored constituencies or cutting indefensible deals with crony contractors. (To judge from the reporting of his international security consulting since then, his conflicts of interest as secretary of state would justify the moniker “Crooked Rudy” far more than any of Hillary Clinton’s alleged misdeeds have justified what Trump called her.)

Giuliani was a self-styled Savonarola who disdained even would-be allies in other branches of government. Even the credit that he claimed for transportation, housing, and safety improvements belongs partly and sometimes wholly to predecessors’ decisions and to economic good luck. (As he left office the New York Times noted that on his first day as mayor in 1994, the Dow Jones industrial average had stood at 3,754.09, while on his last day, Dec. 31, 2001, it opened at 10,136.99: “For most of his tenure, the city’s treasury gushed with revenues generated by Wall Street.” Dinkins, by contrast, had had to struggle through the after-effects of the huge crash of 1987.)

Ironically, it was Giuliani’s most heroic moments as mayor that spotlighted his deepest presidential liability. Fred Siegel, author of the Giuliani-touting Prince of the City, posed the problem when he wondered why, after Giuliani’s 1997 mayoral re-election, with the city buoyed by its new safety and economic success, he couldn’t “turn his Churchillian political personality down a few notches.”

That wasn’t a matter of oversight or accident. Giuliani’s 9/11 performance was sublime for the unnerving reason that he’d been rehearsing for it all his adult life and remained trapped in that stage role. When his oldest friend and deputy mayor Peter Powers told me in 1994 that 16-year-old Rudy had started an opera club at Bishop Loughlin Memorial High School in Brooklyn, I didn’t have to connect too many of the dots I was seeing to notice that Giuliani at times acted like an opera fanatic who’s living in a libretto as much as in the real world.

In private, he can contemplate the human comedy with a Machiavellian prince’s supple wit. But when he walks on stage, he tenses up so much that, even though he can strike credibly modulated, lawyerly poses, his efforts to lighten up seem labored. What really drove many of his actions as mayor was a zealot’s graceless division of everyone into friend or foe and his snarling, sometimes histrionic, vilifications of the foes.

Those are operatic emotions, beneath the civic dignity of a great city and its chief magistrate. Commenting just two weeks ago on New York street demonstrations against Trump’s election, Giuliani warned the protesters that they were “breaking Giuliani’s rules. You don’t take my streets. You can have my sidewalks, but you don’t take my streets, because ambulances have to get through there, fire trucks have to get through there.” But they’re not his streets, and emergency vehicles have a much harder time getting through them during any rush hour than they would with only pedestrians in the way.

I’ve known more than a few New Yorkers, Trump among them, who deserved the bullying Rudy treatment. But only on 9/11 did the whole city become as extreme and operatic as the inside of Rudy’s mind. For once, the city rearranged itself into a stage fit for, say, Rossini’s “Le Siège de Corinthe” or some dark, nationalist epic by Verdi or Puccini that ends with bodies strewn all over and the tragic but noble hero grieving for his devastated people and, perhaps, foretelling a new dawn.

It’s unseemly to call New York’s 9/11 agonies “operatic,” but it was Giuliani who called the Metropolitan Opera only a few days after 9/11 and insisted that its performances resume. At the start of one of them, the orchestra struck up a few familiar chords as the curtain rose on the entire cast and the Met’s stagehands, administrators, secretaries, custodians — and Rudy Giuliani, bringing the capacity audience to its feet to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” with unprecedented ardor. Then all gave the mayor what the New Yorker’s Alex Ross called “an ovation worthy of Caruso.”

9/11 seemed to vindicate Giuliani’s style of governance, some of it retroactively. In 1998, many of us had scoffed as he installed protective concrete barriers all around City Hall, citing the dangers of terrorism. After 9/11, he looked less paranoid than prescient, and many of us were humbled. But when he proposed that his term as mayor be extended on an “emergency” basis beyond its lawful end on Jan. 1, 2002 (it wasn’t), that would have been “a barrier too far” — a small but fateful step toward an authoritarian governance that seeks to eliminate enemies but always ends up only generating more.

Even a stopped clock is right twice a day, and Giuliani was right at times, on a grand civic stage with the built-in limits that constrain a mayor. His bull-headed performance as Trump’s fixer gives a pretty clear indication of why Trump himself should never have been elected. Removing them from public life is imperative to the republic’s survival, but that they’ve ascended as high as they have should remind us that a lot of heavier lifting and repairing will be necessary if and when they’re gone.

I recall when Rudy was paid big bucks by Mexico City to advise the city about its crime fighting efforts. I’m pretty certain that in keeping with his comic book personna, Rudy advised them they simply had too many Mexicans there.