You Don’t Have to Like Everyone, But You Have to Love Them

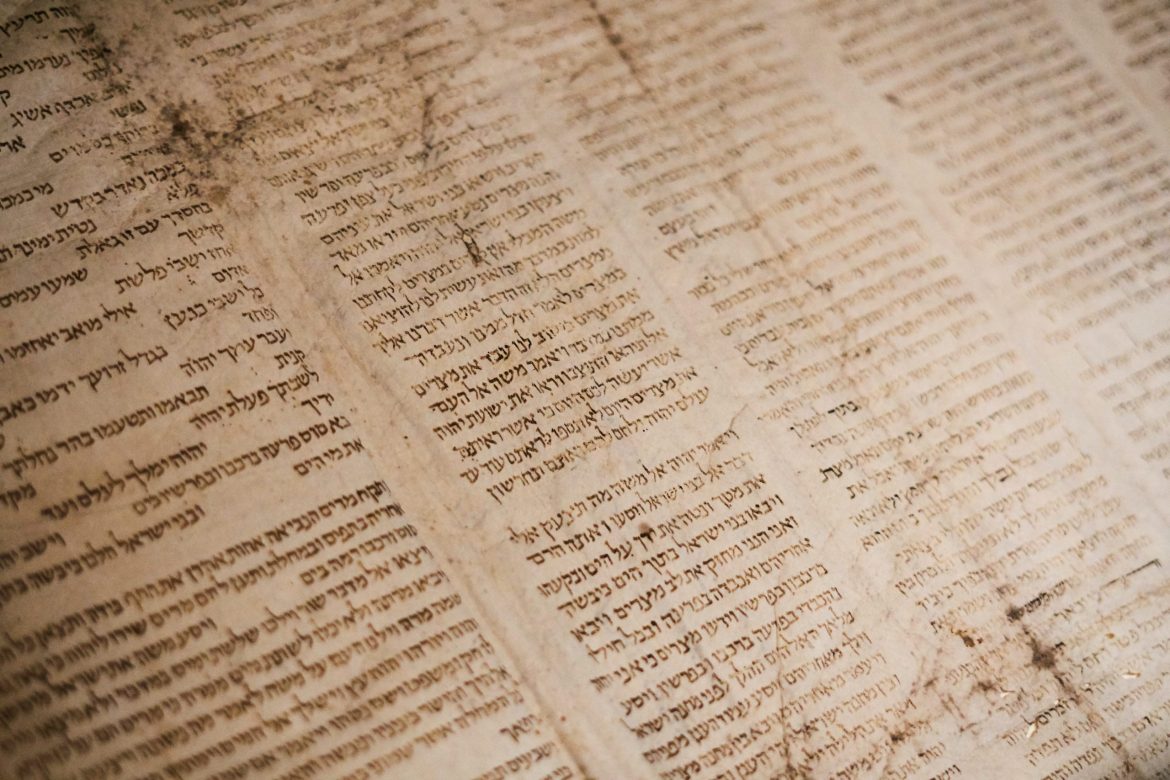

Parashat Vayigash – December 26, 2020

As our neighborhood Black Lives Matter Vigil gathered in the wintry cold, there was not the customary speaker prior to taking our places along Centre Street. Instead, people were asked to bring favorite quotes of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to publicly share. I tucked into the big pocket in my old barn jacket one of my favorite books of Dr. King, his collection of sermons called “Strength to Love.” I had in mind one of his subtler teachings, one that is not carried on his soaring rhetoric, one that I often share, especially with children. It is a teaching not so much about the world, the nation, and society, but about the individual, about ourselves and about our way of interacting with others, particularly with people we might prefer not to engage with. In that way, of course, it does become about the world and about the cosmic interconnection of all life, about how our own individual behavior and ways of engaging with others sends out ripples into the world and becomes an influence either for good or ill.

The essence of Rev. King’s teaching that I had in mind is very simple, and so complex and challenging. It seems almost as a riddle, which is how I present it to children, trying then to resolve what appears to be its paradox, “you don’t have like everyone, but you have to love them.” In a sermon titled, “Loving Your Enemies,” Rev. King gives greater expression and theological underpinning to the tension between liking and loving. Drawing from the Greek, Rev. King speaks of agape as, “understanding and creative, redemptive good will for all (‘men’) people. An overflowing love that seeks nothing in return, agape is the love of God operating in the human heart. At this level, we love (‘men’) people not because we like them, nor because their ways appeal to us, nor even because they possess some type of divine spark; we love every (‘man’) person because God loves (‘him’) them. At this level, we love the person who does an evil deed, although we hate the deed….” As Dr. King contrasts the difference between the romantic love of eros with the love that is agape, it may be similar in Hebrew to the difference between ahava as the love of hearts joined as one, and chesed as loving kindness that is an expression of one’s humanity and that of the other.

Reading Rev. King’s sermon, I thought about Jewish approaches to the same question, of how we respond even to those who would harm us in a way that acknowledges their humanity. It is the great challenge that is planted in the very beginning of Torah, in the sublime and seminal teaching that every person is created b’tzelem elokim/in the image of God (Gen. 1:27). Here, in this noble affirmation of humanity is also planted the painful problem of evil. What happens to the image of God when its bearer does not do it justice, even entirely abusing it through the abuse of other bearers of God’s image, failing to acknowledge either their own humanity or that of others? Yet, because God’s image is planted within every human being without exception, there remains something of the human essence to love. It is that love, I think, which is in part at the root of our horror in the face of vile and violent behavior. Our horror emerges in part in response to that grotesque twisting and violation of the godly image and of all that it means to be human. Our horror in the face of brutality is perhaps an expression of hope, for God protect us if we become numb and fail to be horrified by brutality against anyone. And so too, we are horrified that one can so twist the image of God that has been planted within them.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

As Dr. King draws on Christian sources to teach love of the enemy, so we can look to Jewish sources. In the tension between love and like, as Dr. King draws it out, is a root teaching of nonviolence. Whether in regard to confrontations between collections of people or between individuals, the challenge is to recognize the inherent humanity of the other and to seek points of contact, offering a mirror in which the other might be able to see themself. In the Torah’s way of teaching, we often learn of human behavior and of what we can identify as the ways of nonviolence through stories and situations, challenged to ask what we would do.

There is beautiful teaching to be drawn from the weekly Torah portion that framed that wintry vigil, Parashat Vayigash (Gen. 44:18-47:27). It is a teaching that offers insight into the ways of nonviolence, drawing out the essential dynamic of recognizing the image of God in the other and helping them to do the same. While it plays out through the portion, the essence of the teaching is at the very beginning, vayigash elav yehudah/and Yehudah approached him…. It is the moment when Yehudah steps forward to plead with the viceroy of Egypt on behalf of Binyamin, the youngest son of Ya’akov, the youngest of the brothers, who has been framed for the theft of the royal goblet, now to remain in Egypt as a slave to the viceroy. Not realizing yet that the viceroy is their brother Yosef, whom they had sold into slavery long ago, Yosef does realize that the brothers have surely changed, that their t’shuvah is complete.

As Yehudah begins to plead for the sake of Binyamin, commentators ask what it means that he approached the Viceroy, given that he was already standing right there. In a beautiful commentary that begins with this question, the Or Ha’chaim, a seventeenth century teacher from Morocco, Rabbi Chaim ibn Atar, speaks of a deeper turning that is more than physical. Drawing from Proverbs (27:19), he teaches of a reciprocal approaching of hearts one to another: ka’mayim la’panim la’panim ken lev ha’adam la’adam/as in water, face answers to face; so the heart of one to another…. The Or Ha’chaim teaches that if Yehudah would awaken compassion in the Viceroy, he had to first awaken his own love and compassion for the Viceroy. Only then could he draw Yosef near to him and open Yosef’s heart to receive his words and his effort toward reconciliation. It is a powerful teaching about the dynamics of nonviolence, underscoring that it is not enough to utilize nonviolence only as a strategy. The power of nonviolence lies in heart to heart connection, in seeking to awaken recognition of a common humanity, recognition of the image of God that defines each as a human being. While we cannot like every person, in our love for the humanity of the other we affirm our own humanity and theirs. Having the courage to approach the other, as in water, face answers to face, so the possibility is opened toward rapprochement.

Don’t Turn Off Anger, Channel It

Parashat Vayechi – January 3, 2021

As a child attending summer camp, a large sign on the wall of the dining room continually drew my attention. I was fascinated by this sign and found myself trying to understand it through the time I was in camp and well beyond, continuing to think about it even until today. In large letters, the words on the sign recognized the inevitability of anger, but offered a way of response from within, “Don’t Turn Off Anger, Channel It.” Somehow reassured that it was okay to feel anger, I was not sure what it meant to channel it. Years later, Mister Rogers offered some clarity in the way of practical advice in the moment of anger, sing a song, bang the piano keys, all about finding ways to redirect the powerful emotions seeking resolution. Over time, I came to realize how important it is to talk about anger, not to pretend it isn’t there, to find ways beyond the heat of the moment to talk with the person or people who triggered my own angry feelings.

Smiling at the realization of how it had stayed with me through all these years, I thought about that summer camp sign as I engaged in a conversation with the rabbis about anger. Having already ascertained that God prays, they ask, mai m’tzalei/what does God pray? Perhaps they too had been to my old camp and had seen the sign on the dining room wall and wondered about what it means to channel anger. As much about us as about God, as much about our responses to people as about God’s, so they imagined God’s prayer: May it be My will that My compassion conquer My anger, and that My compassion overcome My strict attributes, and that I respond to My children with the attribute of compassion, and that for their sake I go beyond the strict letter of the law/lifnim m’shurat ha’din (B’rachot 7a).

In the weekly Torah portion Vayechi (Gen. 47:28-50:26), there is a painful reminder of a terrible and terrifying moment of anger, an instance of one of the Torah’s harsh passages, one, as all of them are, that is hard to make our way through. On his deathbed, Ya’akov Avinu, Jacob our father, blesses each of the progenitors of the tribes. We realize quickly that his words are not so much blessings, as they are reflections on the nature and needs of each of his sons. When he speaks to Shimon and Levi together, he harkens back to the horrifying moment (Gen. 34) when they took their swords and slaughtered Sh’chem and Chamor and all of their people; Sh’chem who had raped their sister, Dinah, who it seemed then loved her and sought to marry her; Sh’chem who had agreed to be circumcised, and so convinced all of the other men of his people in facilitating the marriage. We don’t know of Dinah’s own agency, not a word of her insight or desire, only the violent response of her brothers, not clear whether concerned at all for her or only for their own honor. Weak from the circumcision, they were all slaughtered; their city plundered and destroyed, their women and children taken. Certainly unable to channel it, we are told that the events caused Shimon and Levi to burn fiercely with anger/va’yi’char lahem m’od (Gen. 34:7).

At the time of that explosion of anger, Ya’akov was concerned primarily for the wellbeing of his family, worried only that the deeds of these two sons would put the rest of the family in danger as others sought revenge. Now on his deathbed, he is more reflective, more able to see the moral enormity of what Shimon and Levi had done. Speaking to these two, he says: Shimon and Levi are brothers, instruments of violence are their means of acquiring gain…, for in their anger they murdered men…; a curse, therefore, upon their anger, for it is too fierce, and their outrage, because it was too cruel. I will divide them in Ya’akov and scatter them in Israel… (Gen. 59:5-7).

Notably, it is the anger of Shimon and Levi that their father curses, not them. Hope for change is offered, that they might yet learn to channel their anger, to direct their passion and outrage in a more positive way, too fierce, too cruel in the way of slaughter and destruction. That they are scattered in Israel means that they are among us, that they are part of us, of each one and of all of us as a people. It becomes for all of us to consider the way of redirecting their anger and finding other instruments and ways than those of violence for expressing anger and resolving conflict. Scattered among us, perhaps in small doses their anger can become an antidote to our own misdirection of anger and its violent expression.

In a powerfully moving teaching, we learn how the rabbis saw the possibility of channeling such fierce anger, thereby offering a way for all of us to find ways of repair and redirection. They are each given a path of tikun/repair, Shimon to become a teacher of children, and Levi to serve in the Holy Temple and minister to the needs of the spirit, that holy work on behalf of others may awaken a gentler side within themselves. Of Shimon we are told that it was set for him that he shall be a teacher of little children/m’lamed tinokot, and in such a setting he shall teach himself to be moderate in his words and in his deeds, and so shall his anger be repaired/y’tukan al y’dei zeh kaso. Of Levi, we are told that he too shall be given a path to repair, that his service shall only be in the realm of the spiritual/rak ruchani’ut lavad…, and that with God as his portion he shall dwell in houses of study where they engage with Torah, and so shall his anger and wrath find repair/al y’dei zeh y’tukan kaso v’evrato… (Sefer Chochmat Ha’matz’pun).

In their teaching that God prays to overcome anger and give precedence to compassion, and in the way of Shimon and Levi’s repair of anger through service to others, we learn ways to redirect our own anger and channel it to good. Whether or not the rabbis saw the sign that so fascinated me in my old camp dining hall, they too are seeking to answer the question that still comes to me all these years later, rather than turn off anger, how shall we channel it? As the rabbis long ago offered prayer and service as a path to repair, may we seek our own ways of channeling the anger that is ours to redirect. With all the energy of so much anger channeled to good, paths of repair shall open in the world and be the answer to a child’s wondering upon a sign: “Don’t Turn Off Anger, Channel It.”

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.