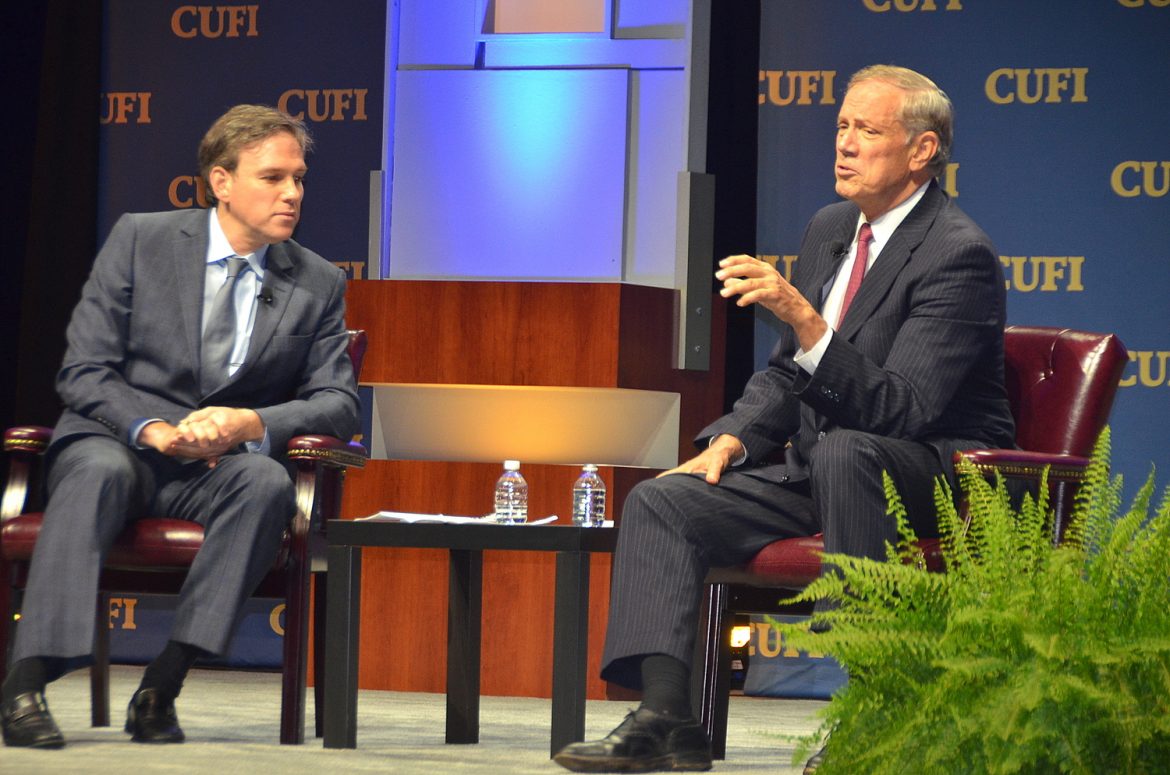

Bret Stephens, then a Wall Street Journal columnist, interviewed former New York Gov. George Pataki on stage at Christians United for Israel’s Washington Summit in 2015. Photo by Maxine Dovere, courtesy of JNS.org.

The Zionist Organization of America’s indulgence of Evangelical Christian Zionist theology, which M. Reza Behman described well here in Tikkun, isn’t just a tactically savvy gambit to attract support for Israel. Whatever this alliance’s actual consequences for Netanyahu government policies, its endorsement, at least nominally, by 40 million American evangelical Christians has ominous implications for Jews’ sense of belonging and security in America — implications that Jewish deal-makers in the ZOA and the American Israel Public Affairs Committee overlook or downplay at their – and the republic’s — peril.

Jews’ expectation of full membership in the early American society of the late 18th century – a fully “enlightened” membership that they hadn’t yet encountered in Europe — began not only with George Washington’s famous letter of 1790 to the Jews of Newport, Rhode Island that affirmed full tolerance of “the stock of Abraham. More surprisingly — and instructively for understanding the Christian-ZOA embrace — acceptance of Jews in America had begun 160 years earlier, when New England Puritans re-interpreted evangelical Christian theology’s certainty that Jews would be “called in” to the Holy Land for Armageddon, where they would either perish in the Rapture of Christ’s second coming or embrace him as the Messiah.

Puritans did assert this. But they also made the somewhat contradictory presumption that New England was the new Zion, because they themselves had superseded the Children of Israel by fleeing “slavery” in England across a sea to establish biblically grounded communities “for the exercise of the Protestant religion, according to the light of their consciences, in the desarts of America,” as the Puritan minister and chronicler Cotton Mather wrote later. But if America was Zion, the new promise land, would the few Jews who lived there at the time really need to go to Palestine for the Second Coming?

Puritan responses were somewhat ambiguous. They didn’t disown or disguise their theological conviction about Jews’ divine destiny, as today’s evangelical Christian leaders — Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, and John Hagee of Christians United for Israel (CUFI) do with supreme hypocrisy, confident of God’s real plan for Jews in the Holy Land.

Early American Puritans left Jews a little more wiggle room, in ways that I happen to have encounter two centuries later, growing up in Longmeadow, MA, an old Puritan town founded in 1690, six miles north of the spot in Enfield, CT, where the great Puritan minister and theologian Jonathan Edwards preached “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” in 1741.

Quite a few of my Longmeadow classmates were lineal descendants of its Puritan founders; the town is the birthplace of Kingman Brewster, Jr., Yale’s president from 1964-73 and a lineal descendant of the Elder William Brewster, the minister on The Mayflower. The family of one of my high school class’ football stars, Will Thayer, had come to Massachusetts in the 1630s, and Will is now a retired minister in the Congregational Church (originally the Puritan church) who spent years working with poor residents of Brooklyn’s beleaguered East New York neighborhood, which I, too, came to know well in writing The Closest of Strangers (which the late historian Christopher Lasch reviewed here in Tikkun in 1990 and re-published as a chapter in his The Revolt of the Elites.)

How had seeds of public obligation like Will Thayer’s and mine been sown in arboreal, somewhat-funereal Longmeadow in the 1950s? Talking with Will and others of my classmates at a high school reunion, I realized that although they weren’t “Puritan,” echoes and remnants of that culture were still with them, and me.

One February morning in 1957, we sat on a classroom floor in the Center School as our 4th-grade teacher, Ethel Smith, read to us, by only wintry light coming through tall windows under charcoal skies, the Rev. John Williams’ The Redeemed Captive Returned Unto Zion, a terrifying account of his and his congregants’ abduction to Canada in 1704 by French and Indian raiders of their Deerfield, MA settlement, 40 miles upriver from us, and of Williams’ return in a prisoner exchange with the Puritan commonwealth years later. His son Stephen eventually became the minister of the Congregational Church not a hundred yards from where we sat as Miss Smith read to us. (In what is surely the strangest coda you’ve ever seen, the future King Abdullah of Jordan was a student at the Deerfield Academy 250 years later. Netanyahu attended Cheltenham High School in Philadelphia before going on to MIT. To see images of both leaders from their high school years, click here.)

On another morning, early in December, 1956, Miss Smith asked me and another boy to stand as she announced that “Jim and Richard are Jewish boys, and they don’t accept our Lord as their savior, and they won’t be celebrating Christmas. But I want you all to know that the Jewish people is a noble and enduring people and that our Lord himself was a Jew. You may sit down now.” Disoriented though I was by that introduction to my schoolmates at age 9, I sensed that Miss Smith meant well in a way that reflected — of all things – some nuances of the evangelical Christian theology that had guided John Williams in Deerfield in 1704 and Jonathan Edwards in 1741. For Miss Smith and descendants of Puritans in the mid-1950s, we Jews had been punished enough by the recent Holocaust; we were no longer ghostly testaments to our own folly in abjuring Christ, but something more like librarians of the Old Testament.

Yale insignia. Image courtesy of Wikimedia.

No matter what Puritans had thought of Jews of their own time (and it wasn’t nice), they’d reverenced ancient Hebrews, whose language they placed on the college seals of Brewster’s Yale and of Dartmouth and Columbia. The Old Testament taught them to ground their salvation-hungry faith in covenanted, earthbound communities of law and worldly work. Even centuries later, some Yankee descendants such as Miss Smith gave us Jews more credit than they gave their fellow-Christian Irish Catholics, such as John F. Kennedy’s clan, whom they accused of corrupting the Protestant-American Zion from Boston.

Let me sketch the somewhat-testy mutual regard between New England Protestants and Jews that would shape the benign American “Judeo-Christian” consensus; then I’ll summarize what each side learned from the other; and then I’ll show why it’s in danger of being destroyed by ugly, opportunistic deal-making among today’s apocalyptic Christian Zionists and strategizing Jewish Zionists.

* * *

For most Americans now, the Hebrew phrases on those college seals and the Old Testament names of many American towns (Canaan, Bethlehem, Sharon, Goshen Lebanon, even Jerusalem) are the only visible remnants of Puritans’ all-but forgotten zeal to Hebraize their Calvinist Christianity in the 17th century. Puritans lost their juridical and ecclesiastical grip on the country centuries ago. And most of today’s American Jews, legatees though they may be of the Hebrew covenant, arrived here too late (and often too lapsed) to seed in religiously Jewish ways the American society that most of them have otherwise so vigorously embraced and engaged.

Yet we need to reckon more deeply right now with the republic’s Hebrew and Christian origins, owing not only to eruptions in the third Abrahamic religion, Islam, but also to the “resurrection” (if I dare use the word) of evangelical Christian theology with the new urgency of Pastor Hagee and others.

Some of these associations do run all the way back to the Puritan settlement: The political idioms of George W. Bush and his neoconservative allies, on the one hand, and Barack Obama and custodians of the civil rights movement, on the other, were staked in Hebraic and Puritan sub-soils that have nourished a distinctively American civic-republican way of life: Harriet Beecher Stowe, daughter of the great preacher Lyman Beecher, a descendant of New England Puritans, wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the novel that galvanized the anti-slavery movement before the City War; Abraham Lincoln read it, and he prosecuted the war in what he came to see as Calvinist terms.

Later in the 19th century, “Social Gospel” crusaders strengthened movements for economic justice: When Theodore Roosevelt challenged the presidency of the latter-day Puritan Woodrow Wilson in 1912, he cried, “We stand at Armageddon” — right here in America — “and we battle for the Lord!”

The historians Perry Miller, Edmund Morgan, John Schaar, Sacvan Bercovitch, and Eric Nelson have shown how American Puritans struggled to ground their Christianity in Hebraic communal discipline as a shield against what they considered the idolatrous corruptions of Rome and the Church of England. William Bradford, first governor of the Plymouth Colony (and my Longmeadow classmate Barbara Hubbard’s ancestor), and Cotton Mather, the sage of Massachusetts Bay and elegist of New England Puritanism, actually learned Hebrew, eager to “purify” their Christianity of its Romish, Latinate encrustations.

Even in 1787, long after Puritanism had lost its iron grip on the country, John Adams, a descendant of Puritans and principal architect and future president of the republic, wrote, “I will insist that the Hebrews have done more to civilize men than any other nation.” He elaborated at some length, averring that he’d insist on its historical truth even were he an atheist.

Adams understood what John Schaar would show in our time—that the Puritans developed a dark genius for balancing Christian spiritual self-absorption with Hebraic social obligation, and personal liberty of conscience and action with public authority. That “balance” sometimes spurred repression, inquisitions, and sectarian hatred. But today’s liberal free-for-all has become an equally dangerous “free-for-none” as our market-mad society has lost its ability to distinguish free spirits from free riders and strong civic tribunes from powers that are intent on compromising them.

Sustaining a republic does require a faith deep enough to stand up to huge concentrations of power. The operative principle, which Puritans got half right, is that while religion can become dangerous in political rulers who impose a state religion, it’s vital to civil society, especially to citizen insurgencies. Whenever faith overreaches, republics falter, but if it disappears completely, they’re lost.

I first learned that one can cherish these old traditions even without believing in them, in 1988, when I became by happenstance the first editor to publish the historian Shalom Goldman discovery, later published in his book God’s Sacred Tongue, that George W. Bush’s great-uncle five generations removed, the Rev. George Bush, was the first teacher of Hebrew at New York University. The Rev. Bush wrote the first American book on Islam, A Life of Mohammed, pronouncing the prophet an imposter, and, more important for our purpose, in 1844 he wrote The Valley of the Vision, or The Dry Bones Revived, interpreting the Old Testament book of Ezekiel to prophesy the return of the Jews to Palestine in a time fast approaching.

I don’t know whether Bush has read his own ancestor’s exegesis, or knows Ezekiel. But Barack Obama certainly does. In his speech on race in Philadelphia during the 2008 campaign, he recalled that at his own Trinity Church in Chicago (a black branch of the Congregational Church, the original church of the New England Puritans), “Ezekiel’s field of dry bones” was one of the “stories—of survival, and freedom, and hope” that “became our story, my story; the blood that had spilled was our blood, the tears our tears.”

Like so many others before him, Obama seemed to believe that the republic must keep weaving into its liberal tapestry the tough, old threads of Abrahamic faith that figured in its beginnings. And now that we’re looking through gaping holes in the neoliberal consensus for old touchstones that are religiously deep, even if not doctrinally resolved, the fate of the republic remains tied fatefully and inextricably to the Puritan claim that the legitimacy of politics depends on the authenticity of its practitioners’ inner beliefs.

The Zionist Organization of America’s alliance with evangelical Christians threatens American civic-republican understandings of Ezekiel like Obama’s because it situates Jews’ destiny wholly in Palestine. Yet the American republic is in deep trouble just now for reasons that Puritans could have parsed with sophistication, even though – or because — they bear some responsibility for its travails. They’d have understood that freedom depends on public virtues and beliefs which a liberal state and “free” markets alone cannot nourish or defend. Somehow, good civic leaders need to be nourished and trained all the more intensively in ways that harness collective responsibility and personal obligation for the common good and even the common wealth.

Puritanism did that. It made ordinary individuals the bearers of a proudly representative republican identity that wealth can’t buy and armies alone can’t defend. Even while cracking beneath the weight of its contradictions in the eighteenth century, it generated a national myth that inspired generations of Americans to integrate personal salvation with social progress and, failing that, to confront glaring but more distant evils such as slavery in the South or terrorism from abroad.

For example, Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement reenacted the Exodus myth in the 1960s, opening the hearts of astonished northern Jews and Protestants whose own ancestors had made history of that same myth in ages past. When, the night before he was assassinated in April 1968, King cried out a line from “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!” that wasn’t just poetry; it was power. Like the Hebrew prophet, who “lives out a myth that may be dead in us and for us, whose fruitfulness cannot be known except by exposing it (and himself) to possible failure,” as political theorist George Shulman puts it, King used speech acts to reintroduce an ancient, sacred past and to make us do a double take on our own emptiness and brutality. So doing, he helped to reenact and shift authority as decisively as Congress did in enacting new civil rights laws.

The historian David Chappell shows memorably in A Stone of Hope that King and other movement activists absorbed and relied on the Puritan-Hebrew synthesis to sustain themselves. Knowing what American Christians and Jews have learned from one another is critical to understanding what we’re missing now, even if we can’t quite recover it. So let me sketch what each side learned from the other but that both sides are in danger of forgetting.

* * *

The constitutive act of Judaism was an unprecedentedly stark separation of spirit from nature that transformed human self-consciousness. It turned the enchantments of natural cycles and sacred physical sites into soaring new aspirations, projected into the vast unknown between human beings and God. That prompted restless yearnings to know and do God’s will on earth.

According to the Bible itself, the sublimity of its great separation of spirit from nature didn’t last long. Like Blaise Pascal, who exclaimed millennia later that “the eternal silence of those infinite spaces terrifies me,” ancient Hebrews fled that silence quickly, indulging in idol worship and, later, kingly arrogance and priestly legalism. Some say that first the prophets, and then exile, purified the Jews and their transnational mission, but Puritans grounded their “errand into the wilderness” only in ancient Hebraism’s sublimity and inflected nationalism, believing that other Christians had succumbed to a hypocritical other–worldliness.

Here, then, is what the founders of American Puritanism drew from Hebraism:

The Making of History. The Hebrew word ivry—related to the Hebrew word for Hebrew—means “he crossed over,” denoting Abraham’s response to God’s command to separate himself from his tribe’s sacred groves and rites. Abraham smashes idols and even prepares to sacrifice his son Isaac to God. His loneliness approaches existential grandeur, but biblical Hebraism, taking its sublimity straight up, turns natural beauty into a metaphor of man’s futility. In the words of the Yom Kippur liturgy, “He is as the fragile potsherd, as the grass that withers, as the flower that fades, as a fleeting shadow, as a passing cloud, as a wind that blows, as the floating dust, yea, and even as a dream that vanishes.”

Where the Hellenism that we know from ancient Greek texts united love and nature in timeless cycles and embraced the world as it is, Judaism forces the imagination away from graven images and toward action for ends that haven’t been attained yet on earth. It finds beauty in the arc of the deed that pursues justice across time.

As the late Yirmiyahu Yovel, the Israeli philosopher, biographer of Spinoza, contributor to Tikkun, and Israeli Army intelligence officer, puts it in Dark Riddle: Hegel, Nietzsche, and the Jews, human subjects began to identify their own purposes with the transformation of a world that wasn’t wholly indifferent to their efforts, but only when they acted through a covenant with the often-hidden God: Abraham’s grandson Jacob wrestled with an angel all night, trying to wrest truth from God, and at dawn the angel renamed him Yisrael, which in Hebrew means, “He wrestles with God.” Many of us wrestle that way even now, seeking something like teleological significance in our deeds. Puritans did that all the time.

Inflected Nationalism. To cope with the vast unknown it opened between man and God and between present and future, the Hebrew religion harnessed the nationalism of a people chosen by a mysterious, irascible interlocutor. “I will make thee a numerous and great nation,” God promises Abraham as he orders him up and out of his past. But Abraham’s nation is sundered from its Promised Land early and often because its territorial claims are contingent on keeping the covenant. This gives the Hebrew a strange new orientation on earth: “The Jewish nation is the nation of time, in a sense which cannot be said of any other nation,” observed the Protestant theologian Paul Tillich:

“It represents the permanent struggle between time and space. . . . It has a tragic fate when considered as a nation of space like every other nation, but as the nation of time, because it is beyond the circle of life and death it is beyond tragedy. The people of time . . . cannot avoid being persecuted because by their very existence they break the claim of the gods of space, who express themselves in will to power, imperialism, injustice, demonic enthusiasm, and tragic self-destruction. The gods of space, who are strong in every human soul, in every race and nation, are afraid of the Lord of Time, history, and justice, are afraid of his prophets and followers.”

From its biblical beginnings, then, this tribe coheres through its unprecedented negation of what’s usually tribal and through its imaginative, sometimes brilliant defiance of what Tillich’s lords of space and power demand. This isn’t the defiance of the world shown by John Bunyan’s pilgrim Christian, who sets out from the City of Destruction in The Pilgrim’s Progress to seek the Celestial City in Heaven. He leaves the world alone and vertically, as it were, abandoning its space in pursuit of life after death. The Jew, by contrast, remains in earthly space but traverses it collectively, on God’s time, thinking not of his own ascent but horizontally, across generations: “In every generation let each man look upon himself as if he came forth out of Egypt,” says the Haggadah of the Passover seder, which celebrates the Exodus. Puritans yoked this earthbound myth to Bunyan’s.

Collective Punishment and Mutual Obligation. The Hebrew narrative depicts its chosen people as sometimes servile and stiff-necked. They fall on their faces before God when thunder sounds or miraculous deliverance comes, but they grumble moments later and worship that golden calf at the very foot of Mount Sinai. They don’t want to serve the Lord of Time as much as they wish to return to the pagan unity of love and nature.

When the people break the covenant, they’re punished collectively, not individually: Jewish tradition (and, later, the Jews’ experience as a vulnerable minority) reinforce an obligation not to get the whole community into trouble by sinning. Personal responsibility is socialized: The Jew “repents not only of his actions, but for the ‘root’ of his actions,” observes the French Protestant philosopher Paul Ricoeur. “Thus the spirit of repentance discovers something beyond our acts, an evil root that is both individual and collective, such as the choice that each would make for all and all for each.” Under certain circumstances, that could be a strong spur to what we now call “social action.”

This fear of collective punishment relies less on personal introspection than on the individual internalizing a common destiny. When Moses presents the law at Sinai, the people respond, “We will do and we will listen,” and later commentators interpret that vow as evidence of Hebraism’s emphasis on fulfilling one’s obligations before indulging any doubts about their provenance.

Hebraism thus abjures not only the Christian pilgrim’s lonely departure from the world but also Hellenism’s inclination to know the world rather than change it. Hellenism imparts to life an “aerial ease,” a “sweetness and light,” according to Matthew Arnold, who, in Culture and Anarchy, contrasted that felicity with Hebraism’s scourging demand for “conduct and obedience, mediated by strictness of conscience” in the fulfillment of its historic mission:

“To walk staunchly by the best light one has, to be strict and sincere with oneself, not to be of the number . . . who say and do not, to be in earnest—this is the discipline by which alone man is enabled to rescue his life from the thralldom of the passing moment. And this discipline has been nowhere so effectively taught as in the school of Hebraism. . . . [T]he intense and convinced energy with which the Hebrew, both of the Old and of the New Testament, threw himself upon his ideal, and which inspired the incomparable definition of the great Christian virtue, Faith—the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen—this energy of faith in its ideal has belonged to Hebraism alone.”

Prophetic Dissent. Covenantal commitment can curdle into priestly conceit and soul-suffocating legalism. That, in turn, can prompt individuals who’ve kept the “true” spirit of Israel’s pact with God to challenge the afflicted society to recover its original purpose. The yearning for such renewal is a wellspring for both Hebraic prophecy and the Puritan jeremiad—not to mention a lever for change.

Most of Christianity treats the biblical prophets only as prefigurations of Christ, who turned the prophetic impulse from this world toward reconciliation with our father in Heaven. Judaism holds out for tikkun olam, the repair of this world.

In Dark Riddle, Yovel adds that Jews tend to think that Christians, fearful of earthly separation from Spirit, “tried to bridge that hiatus by presenting God as a suffering, agonizing man; but thereby it transformed a human need into a theological principle that ends with an illusion” and “(in Maimonides’ view) in a false consolation.” For two millennia, Christians intoned, “My kingdom is not of this world” and claimed that “Baptized in Christ, there is no Jew or Greek,” yet they sat on golden thrones over well-armed states and sacralized national identities that were even more rooted in “blood and soil” than the ancient Hebrews.

That’s exactly what Puritans meant to correct. While Bunyan’s Christian fled his city, the Puritan minister engaged it, with Jeremiads such as Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” in the name of the community’s past and divine mission on earth.

Jews would learn something from this, including new ways to make history within a civic-republican faith that sometimes pits personal honor against the state, as in the American Revolution. Not only has the Christian emphasis on inner renewal and personal witness sustained the republic at times when nationalism and legalism couldn’t; civil-society movements have brought down armed regimes, including in the American South, by joining Christian personal renewal to Hebraic covenantal commitment in nonviolent collective strategies that the Hebrews themselves hadn’t imagined.

I certainly hadn’t imagined it until I encountered that combination one one wintry morning in 1968, my junior year at Yale, when I stopped on my way to class to watch a small, quiet demonstration at which Yale’s theologically Calvinist but politically radical chaplain, William Sloane Coffin Jr., accepted the draft cards of three students who were refusing conscription into the Vietnam War. “The government says we’re criminals,” said one of them, a fine-featured scion of the old republic, his voice shaking a little over his fear, “but we say it is the government that is criminal for waging this war.”

“Believe me,” Coffin responded, “I know what it’s like to wake up in the morning feeling like a sensitive grain of wheat, looking at a millstone.” It was a ray of Calvinist humor, a jaunty defiance of established power in the name of a higher power, of defiance of tyranny as obedience to God, and we grasped at it because we were scared. For all we knew, these guys were about to be arrested on the spot, and we were awed by their example, carrying as we did our own draft cards in our own wallets.

Coffin was there to bless, in an American civic idiom that too few liberals now understand, a courage that too few national-security-state conservatives understand. A few yards away, the names of hundreds of those Yale men who’d perished in wars were inscribed in icy marble under the admonition “Courage disdains fame and wins it.” Now some living Yale men were challenging us to join them in disdaining fame, but with scant prospect of even a memorial’s posthumous regard.

Something in their bearing made them intrepidly “Puritan” in the ways I’ve sketched, and heroically free of anything anti-American, as Rosa Parks had been when she’d refused to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery a dozen years earlier. The dignity in such protests redeemed a corrupt civil society instead of trashing it as inherently damned. Now these Yale students were resisting the government in the name of a society that they, too, were reconstituting by pledging their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor. It was as if the civic spirit had risen from a long slumber and was breathing and walking again, re-moralizing the state and the law.

“The great glory of American democracy is the right to protest for right,” Martin Luther King Jr. said during the 1950s and ‘60s, and the German philosopher Jurgen Habermas marveled at what he called the “constitutional patriotism” of Americans in the civil-rights and anti-Vietnam War movements who confronted the state not in the name of nationalist fantasies of sacred blut und boden, blood and soil, but on behalf of an experiment that would test, as Lincoln put it, whether republics relying on a higher faith and virtue can long endure. I don’t see how “constitutional patriotism” like this can be understood without reference to the Puritan and

Hebraic wellsprings from which King, and others drew the strength to face dogs, fire hoses, and even murder.

Puritans whose theology still influenced Coffin and King believed that while the covenanted community could shelter and guide the individual flame, it hadn’t created it. That came from God, and that conviction could hearten dissenters. While the community too often went so far in judging others that it conducted witch hunts, the depth of Puritan conviction also inspired death-defying dissents, as when Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams accused Puritan elders of valuing power more than faith. (It even inspired fasting and repentance for the Salem witch hunts, one of whose judges, Samuel Sewall, confessed his guilt publicly.) Think, too, of the early abolitionists, many of them Puritan to the core.

Sometimes almost despite itself, then, early Protestant Christianity in America gave to conscientious dissent a legitimacy and strength that Hebraism had not. But Hebraism offset Christian tendencies toward monkish or airy otherworldliness with a moral order grounded concretely in law.

For complex reasons, this creative tension would snap or dissipate, especially after Woodrow Wilson’s war-making left a generation of Americans disillusioned and racing toward a City of

Destruction, which spawned the Great Depression and yet another world war. In the 1920s, the writer Van Wyck Brooks observed that as the old jug of Puritan wine finally cracked, its liquid ran to earth as rank commercialism, and its vapors floated up into airy transcendentalism.

Unlike the Hebrews, earnest legatees of the Puritans even through the 1940s remained obsessed with justifying every political act by the authenticity of the actor’s inner belief. The novelist Henry James reproached “the hard glitter of Israel” that he saw in Jewish immigrants to New York. These Jews were too pushy, not introspective enough. They had merit in performing duties; but did they have inner integrity?

The hypocrisy in Puritans’ sanctimonious scrutiny of the newcomers was captured by George Santayana:

“The old Calvinists . . . had flattered themselves that at least the Lord, if no one else, particularly loved them, that God had sent down Moses and Christ to warn them of the dangers ahead, so that they might run in time out of the burning house, and take all the front seats in the new theater. [They] wanted . . . to find, in some underhanded way, what was the will of God, so as to conform to it and be always on the winning side.”

Puritans also couldn’t reconcile their belief in inscrutable, godly grace with their temptation to regard rewards of material striving as signs of grace. Like Hebrews worshiping a golden calf even while receiving the covenant, they forgot John Winthrop’s warnings against “carnal lures,” by which he meant ostentatious consumption as well as sexual temptations. Puritanism had moved mountains with faith while it was insurgent against greater powers. But its reliance on justification by faith more than by works was always vulnerable, particularly to the demands of an open continent and a dynamic liberalism.

* * *

Fortunately, between the rank commercialism and empty transcendentalism of the 1920s, there came a civic-republican condensation in the middle, a synthesis to which Jewish immigrants brought the skills and aspirations of modernity and their old covenant’s moral rigor. This was staunchly resisted by some latter-day Puritans, who, like John Adams and the Rev. George Bush, admired ancient Hebrews but hoped that restoring the Jews of their own respective times to “Judea” (as “an independent nation”) would help them shed what Adams called “the asperities and peculiarities of their character.”

Yet Jews in America have matched the cultural influence of Miss Smith’s flinty, testy New England Yankees, who had their own asperities and peculiarities. Jews have played pivotal if conflicting roles as carriers of both the ancient Hebraic and modern Enlightenment strains. The best of this vitality was badly needed by a still-Calvinist but faltering and hypocritical American public culture. Ironically, though, most American Jews—arriving long after Adams and Bush had directed their forebears to Palestine—proved only too ready to exchange covenantal baggage for the offerings of a liberal, individualist civil society, even one that, at the time, retained strong Puritan-Hebraic foundations.

History has presented Jews with an arresting irony, however: Even when they have abjured their ancient, revolutionary, and cosmopolitan faith, it still has driven their historical fate. They are passionate about America not only because they’re relieved to have escaped a long nightmare in Europe but also because the old Hebrew faith has figured so decisively in the building of the republic itself. Free of Christian preoccupations with personal salvation—free also, largely, of specific rabbinic constraints—yet still driven by elements of the ancient faith as well as by their more recent historic fate, many Jews embraced a secular civic covenant that entwined personal renewal with public progress.

Although a minority of these new Americans – neoconservatives among them — have let carried Jewish historical scars as fresh wounds that drive them to gratuitously bombastic nationalism and militarism, most American Jews have been keepers of the civic-republican balance of public obligation and inner integrity. Recognizing this, the mid-20th century American Lutheran theologian

Reinhold Niebuhr became philo-Semitic in ways that made a difference. As a young Detroit pastor in the 1920s, he scolded anti-Semitic evangelical Christians for being “un-Christlike.” As a Christian Zionist, he had favored converting Jews instead of persecuting them, but he became the first prominent American Christian theologian to oppose both conversion and persecution. Working to improve race relations while a pastor in Detroit in the 1950s, he is said to have told a colleague that, among the participants in that effort, “two of the best ‘Christians’ are Jews.” In 1966, he told the liberal Catholic journal Commonweal that “the genius of Christianity was rooted in its Hebraic conception of life.”

Anyone who understands Puritanism will also understand why Kingman Brewster, Jr’s honoring of King with an honorary doctorate of laws at Yale’s 1964 commencement was condemned by some alumni who thought King a law-breaker and rabble-rouser. The old tension between temple priests and prophets, between worshipers of the Golden Calf and keepers of the covenant, persisted even in the new Zion that Brewster’s ancestors had founded. It was Southern blacks, descendants of Africans who’d been abducted and plunged into the new Jerusalem as slaves, who knew best what many of the rest of us had forgotten: that the Exodus may unfold only across a lot of wandering in the wilderness, of facing brutal attacks, and of worshipping golden calves. I can’t imagine neoliberals or neo-conservatives facing dogs, fire hoses, or prison on their way to a promised land. But, that’s what it may take to defend and advance a just society in our own time.

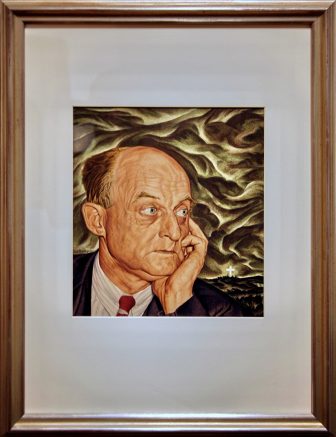

Reinhold Niebuhr, 1948, Gouache on board by Ernest Hamlin Baker. Image courtesy of Cliff/Flickr.

Reworking some of the old Puritan teachings, Reinhold Niebuhr re-interpreted the Gospel of Matthew’s puzzling injunction to Christians to be “wise as serpents” yet “guileless as doves.” Niebuhr warned Americans, as he might have counseled some of today’s Zionist Jews and Christians and even their progressive opponents, to credit the biblical serpent and his kind, “the children of darkness,” with being wise enough to see that selfishness is irrepressible in all humans, but to avoid misusing such “wisdom” to manipulate and discourage those who would lead by wiser example, pursuing tikkun olam by organizing and working for justice and comity.

Niebuhr cautioned the “children of light” to “be armed with the wisdom of the children of darkness but remain free from their malice. They must know the power of self-interest in human society without giving it moral justification.” They mustn’t lose their ability to be guileless as doves when conciliatory and trusting behavior are possible. As Jesus put it, “Be ye as deceivers, yet true.” And as the epitaph on the grave of Kingman Brewster, Jr., that descendant of Puritans, puts it: ”The presumption of innocence is not just a legal concept. In commonplace terms it rests on that generosity of spirit which assumes the best, not the worst, of the stranger.”

Niebuhr also taught that although the children of light have their own darkness, or blind spots, the children of darkness have some light in them that’s struggling to get out but that’s blocked or miscarried by their own gnawing fears and compensatory overconfidence. American descendants of the indomitable ancient Hebrews and intrepid 17th-Century Puritans may take awhile to learn that a society that consumes itself in making war abroad or on its own streets makes itself weak in ways that the would-be warriors tend to ignore: Regimes and populations armed to the teeth quite often lose the wars they fight, and, losing them, they end up seeking scapegoats, even in groups that have tried hard and in good faith to join them.

Learning this difficult lesson in America may require incorporating even while transcending some elements in the old Hebrew and Puritan traditions that I’ve sketched here. To do that well, not recklessly, Americans need to rediscover how Puritan and Hebraic currents combined personal struggles with communal strengths, elevating ordinary individuals to embrace and carry redemptive republican obligations. Although the Puritans were flawed in ways we see only too well, they were wise in ways that today’s enflamed Christian and Jewish Zionists collaborators seem to have forgotten.

The Christian historian William Vance Trollinger, Jr. observes that “Many Jews in the United States and in Israel are willing to swallow their concerns and accept the support of Hagee and other Christian Zionists. Trollinger cites former American Israel Public Affairs Committee researcher Lenny Davis saying, “Sure, these guys give me the heebie-jeebies. But until I see Jesus coming over the hill, I’m in favor of all the friends Israel can get.’ Trollinger warns that “Such thinking might make sense in the political short-term, but enabling such typecasting carries with it significant dangers, given that the prophetic script can change (particularly if Jews do not play their Christian-assigned roles).

It’s time for American Jews to get more than the heebie-jeebies. When New York Times columnist Bret Stephens was editor-in-chief of the neoconservative Jerusalem Post in 2003, he characterized Christian Zionists as “a huge reservoir of support” that Jews would be “stupid to spurn, especially when we don’t have so many friends and allies.” Even as late as 2015, as a columnist for the Wall Street Journal, Stephens agreed to interview American presidential candidates for Pastor Hagee’s Christians United for Israel: (Here’s a photo and account of Stephens doing just that.)

By 2013, he had become so politically correct and protectively censorious on behalf of Zionism that even Jeffrey Goldberg, a staunch Zionist himself (and now the editor of the Atlantic magazine) criticized Stephens for charging that there was an “olfactory element” in Senator Chuck Hagel’s remark to former American Middle East negotiator Aaron David Miller that “the Jewish lobby intimidates a lot of people” on Capitol Hill. Stephens’ suggestion that Hagel might have “a Jewish problem” was roundly discredited by Jewish and Christians who had worked closely with him.

Stephens supported Trump’s moving America’s Israel embassy to Jerusalem and his withdrawal from both the Kyoto and Iran nuclear agreements. But Trump did worry him, and when the Zionist Organization of America invited Steve Bannon to address a conference in 2017 and gave him a standing ovation, Stephens seems to have understood at last that his fancy dancing with ugly, opportunistic deal-making had to stop. “When a right-wing Jewish group such as the ZOA chooses to overlook Bannon’s well-documented links to anti-Semitic white nationalists, it puts itself on a moral par with J.V.P.“ — the “far left Jewish Voice for Peace,” as Stephens characterized an organization whose advisory council includes Tony Kushner, Noam Chomsky, Naomi Klein, and Wallace Shawn.

ZOA members who indulge a Christian Zionist theology that’s even more apocalyptic than that of the Rev. George Bush in 1844 are hollowing out American Jewry’s and the American republic’s fragile foundations. They’re enlarging the frightening civic vacuum into which have swept Glenn Beck, the torch-bearing, anti-Semitic Charlottesville rioters, and the perpetrator Pittsburgh synagogue massacre. If ZOA members really want to ally with today’s Christian Zionist leaders, they leave the United States, as Benjamin Netanyahu left his sojourn in the dubious “Zion” of Philadelphia.

Deeply supportive though I am of Israel’s flourishing — albeit on somewhat more just, confederative terms such as those that Bernard Avishai sketched in the New York Review of Books (and that Netanyahu rejects and thwarts at every turn) — I’ve tried to show here what Jews will lose in America if their support for Israel remains as compromised as that of Zionist deal-makers, both Christian and Jewish, who are squandering the credibility they once had with young Americans of both faiths who cherish but wrestle with the blessings of the American republic. J’accuse.

A bigger concern for American Jews , should be Jews for Trump !

Who called Nazis , Good people about a year or so ago, I guess the KAPO’s just come out when self interest takes over the fellow human being’s !

John F. Kennedy’s clan, whom they accused of corrupting the Protestant-American Zion …

Seeing Derry, the Protestant Jerusalem, has displaced Irish for 400 years I would imagine the Kennedys were quite familiar with Zionism prior to America existing.

Here’s what I don’t understand: you impressively sketch the early history of American Protestant theology and its Jewish-erasure tendencies, and draw a line straight from there to the modern Jewish-erasure movements like the Black Hebrew Israelites and their underlying theology. So why do you act like this is a good thing? It’s brought tremendous pain on American Jews and on Jews worldwide. It has had enormous repercussions in our present-day experience of antisemitism. Why would you treat it as a positive thing that was good for us?

Come with me, and you’ll be, in a world of pure imagination