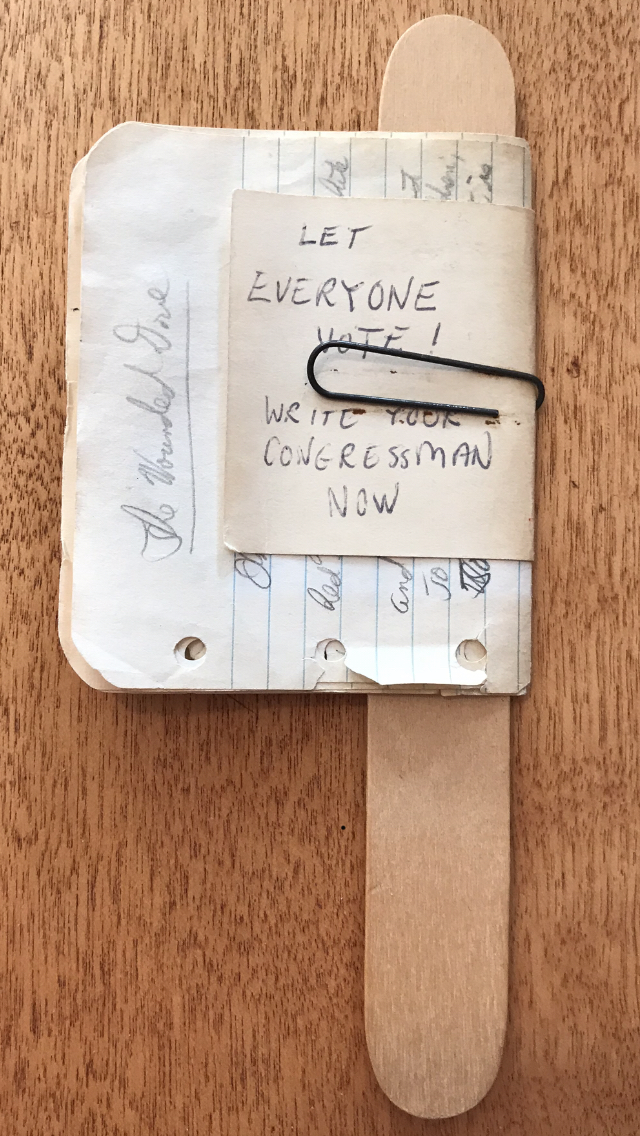

In the current climate of voting rights under attack, particularly galling to me is the cynical chipping away at the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, which built on the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Too young to travel south to help in efforts to register Black voters, I sought other ways to participate in the struggle. A small artifact on a shelf behind my desk tells the story. Appearing as a miniature sign or placard, it is the template for a larger sign to be held in a vigil. Formed of a business card folded around the thin slat of a tongue depressor, the block letters on the back of the card proclaim with urgency: LET EVERYONE VOTE! WRITE YOUR CONGRESSMAN NOW. The business card is that of the Protestant minister with whom I stood in a weekly vigil after school in Winthrop, Massachusetts through the school year following my Bar Mitzvah. We stood in front of the post office as the only federal building in town, the two of us alone, urging passage of what would become the Civil Rights Act.

Innocence was shattered during that year. I heard words I had never heard before, embarrassed to tell my parents, threats and taunts hurled from passing cars, the intent clear if not the meaning of each vile utterance. Barely aware of the words, I was introduced that year to the raw hate that feeds racism and antisemitism. Somehow they knew that I was Jewish, perhaps from a local newspaper article and accompanying photograph about the vigil. “Jew” and its pejorative forms that I had never heard before and the vile N-word joined with lover were for them fitting missiles with which to deliver their hate, words meant to demean entire peoples used as swear words with which to curse individuals. From a place of bewilderment and pain, though with an increasing sense of perseverance and pride, I struggled to understand how people could hate like that. So too, these encounters became lessons in learning to love in response to hate. I learned the role of the lone voice seeking to move others, determined in tone and timbre to retain its own integrity and dignity, not to succumb to the seductively cathartic ways of hate and violence. Here, within the city, the public library and the town hall on the green across the street told of ideals and aspirations, of books and ideas, of civics and civility. Children made their way home from the nearby elementary school, some quizzical, the occasional one even stopping to ask why we were standing there, taking thoughtful note of our presence within the city, most simply delighting in their afterschool freedom. Younger ones walked hand in hand with parents, adults bemused or sullen as they hurried by, children wondering, asking, all inevitably touched by the swirl around them, souls imprinted with the sounds and sights of rage and witness, innocence offering no protection.

As encountered throughout life, from the first peeling away the veil, unraveling the skein of innocence, these are the questions that are meant to challenge us through the lens of Parashat Vayera (Gen. 18:1-22:24), continuing through Torah, and on into life, a portion filled with human triumph and tragedy, and in its midst a paradigm for speaking truth to power. They were questions intuited but unformed then for a young person standing in silent witness, a Torah portion that would become beloved to him, questions pulsating yet in this time – “LET EVERYONE VOTE!” – in all times: questions of justice and decency, questions of moral witness and its limits, of the one and the many, of collective responsibility and accountability, the guilt of leadership and the suffering of innocents. That we are called to act is made clear before Abraham models the way, rising to the call. Of cities consumed by violence and hate, as the text is read by the rabbis, it is the suffering of one young girl brutally tortured for showing kindness to a stranger, she whose cry rises to heaven. Responding to the suffering of one, even as it is one who will bear witness, in a moment of divine soliloquy, God weighs whether to confide in Abraham the contemplated destruction of the cities, needing to see what Abraham’s response will be, whether or not he will intercede, even for the sake of the wicked. This is why God has sought out Abraham, only so that he may command his children and his house after him that they may keep the way of God/v’shamru derech ha’shem — to do righteousness and justice/la’asot tz’dakah u’mishpat… (Gen. 18:19). Meeting the challenge, Abraham boldly steps forward and asks if the Judge of all the earth shall not do justice. Beginning with fifty, perhaps there are fifty righteous within the city/b’toch ha’ir, and God promises to forgive for the sake of fifty righteous within the city, and so the emphasis throughout, down to ten.

We come to understand what is meant, for them and for us. There are those who are righteous at home, but who fail to raise their voices in public, b’toch ha’ir/within the city, those who fail to do righteousness and justice, who fail to resist and rebuke for the sake of the common good. In a powerful warning against the smugness that can infect religious observance, against the deceptive lure of withdrawing and seeing oneself as being above the fray, the Oznaim La’Torah, Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin (Poland-Israel, 1881-1966), probes why the emphasis on b’toch ha’ir/within the city: because there are righteous people who live in the city, but not within the city; who cloister themselves only within “the four ells (cubits) of halacha,” (only within the narrow, protective parameters of their own observance); righteous people such as these don’t seek to influence the people of the city, nor to return them to the right path/v’lo yach’ziru otam l’mutav…. Reminding that God’s call to Abraham echoes through the generations and that Torah is a context in which we are to wrestle through its stories with all realms of human strife and struggle, Rabbi Sarotzkin emphasizes the duty to so teach children, our own and all of those who pass by within the city: one needs to tell in the ears of children and children’s children/tzarich l’saper b’oznai banim uv’nai banim, that stories such as these/sipurim k’eleh are designed to train them and make them wise, to turn from evil and to do righteousness and justice/la’sur mei’ra v’la’asot tz’dakah u’mishpat….

Wrestling with the efficacy of the lone voice, hope carried in the question of a child, as though of those who stand in vigil within the city, Elie Wiesel, of blessed memory, weaves a midrash that reflects his own horror before the crime of silence: A person came to the wicked cities of Sodom and Gomorrah to plead with the people to turn from their violence, to stop their killing. This person walked the streets of the city day after day talking and pleading, but alas to no avail; the people continued in their violent ways. One day, as the person walked through the streets of the city, a child came up and asked, ‘why do you continue to talk to them, you see that they don’t listen to you?’ And the answer came gently to the child, ‘When I came here, I talked to them in order to change them, now I continue to talk to prevent them from changing me.’

If only for the sake of one, the one of lonely voice, the child who barely knows how to ask, God in whose image of oneness all are created, however many times we have been there with Abraham, we nevertheless still sit at the edge of our chair, hoping he will keep going, pleading all the way down to one. Ten comes to represent the collective, the critical mass; the tipping point beyond which it is too late for survival of earth, of people and place, innocence offering no protection. Extended from a gathering of ten Jews for public prayer, minyan becomes the symbolic locus of moral responsibility.

From adolescence to young adulthood, less than a decade after the vigil in front of the post office for the right of all to vote, the Vietnam War by then in full fury, I was serving a jail sentence in the Worcester County Jail in Worcester, Massachusetts for sitting in at a draft board. My beloved rabbi, Rabbi Meyer Finkelstein, of blessed memory, wrote a precious letter to me in jail, affirming my path of witness. Drawing on Parashat Vayera, he offered insight into a midrash (B’reishit Rabbah 50:5) that ends with the words not one of them protesting, and so explaining, he spoke to my soul: “Abraham argued with God to try to prevent the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. The Rabbis explained that destruction by posing a question and then answering it. They asked – ‘surely not all of the residents of Sodom were people of violence. Why were all the people destroyed?” Then they answer – ‘Those that were not men of violence and crime committed an even greater sin. They stood by and never raised their voices in protest. They thereby acquiesced to violence and crime and sin.’”

The painful lesson of Torah is that more than one is needed to avert destruction. Sometimes, though, it begins with the voice of one, of one and one become two, of a child asking why we stand in the face of hate, become ten, become fifty, and in the echoing voice of Pete Seeger, of blessed memory, “if one and one and fifty make a million, we’ll see that day come round….” It is the hope of a small template for a sign to be held in a long ago vigil within the city, an artifact and its message that endures, words of witness to remind, words whose urgency is no less today than it was then, proclaiming in block letters, “LET EVERYONE VOTE!”