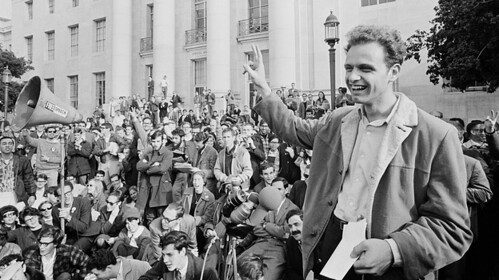

Students at a FSM rally at UC Berkeley's Sproul Plaza on Dec. 9, 1964. Credit: Creative Commons/ Sam Churchill.

I walked into Sproul Hall in my fluffy pink sweater embroidered with flowers, and my blue corduroy jeans. In my ears were gold loop earrings, also decorated with flowers. My long dark hair was pulled back in a pony tail. That outfit seems to me now to be a symbol of my innocence, even naiveté.

The Free Speech Movement grew on the Berkeley campus of the University of California in the fall of 1964, culminating in the sit-in at Sproul Hall, the campus’s administration building, and the arrest of participating students on December 4th of that year. It was the first major student demonstration, and is generally regarded as the beginning of the Student Movement, which spread throughout the United States and even to other parts of the world.

I remember walking around campus with my blue canvas book bag in early December, as the tension grew. I bumped into friends who, like me, supported the movement, but for a variety of reasons were not willing or able to take part in the sit-in.“I might get deported,” said the foreign student from Japan.

“I might not get the security clearance I’ll need for my work” said the Physics grad student.

All true, I thought to myself: But somebody’s got to do it. It might as well be me. As it turned out, on a campus of 27,500 students, only about 800 were arrested.

I took my place on what I think was the third floor of the building, sitting on the marble floor, and waiting. Michael Lerner was conducting a Chanukah service in a different part of Sproul Hall, but I didn’t know that. Communication within the building left something to be desired. Each floor was like a little ghetto, isolated unto itself. Some of my fellow residents of the third floor had brought text books to study for finals. (This was well before the day of laptops, of course.) I hadn’t. I just sat there waiting.

I was 20 years old, and I had grown up in a sheltered suburban community of Los Angeles. I was arrested under my maiden name, Margaret Irving. My father’s family name was Israel, but at a time of greater anti-Semitism, he and his siblings changed it to Irving. When I got married I changed it back.

My brother and I were what I thought of as pink diaper babies. Our parents weren’t communists, but they had friends and relatives who were. Nevertheless, when I called my mom after we were released from “jail” – in our case, the National Guard Armory – to tell her that I had been arrested, she asked if I had walked out of the building under my own steam.

“No,” I admitted, “I was carried out.” “By two burly policemen,” I added.

“That certainly wasn’t ladylike,” she snapped.

For her, being a lady trumped being a radical. Or maybe, nothing I did during that period of time could have pleased her.

I desperately wanted my parents’ approval, but it was not forthcoming. They didn’t want me to ruin my future. My younger cousins, however, were thrilled. My uncle, the father of my younger cousins, was part of The American Civil Liberties Union pool of lawyers who defended the arrestees pro bono. He was wiser, as it turned out, than my parents: He told me that he was proud of me, and at the same time gently advised me to plead nolo contendere, which meant that I would get off with a year’s mild probation. The only condition of this probation was that I not participate in a political demonstration for the next year, and then – because I had been a minor at the time of my arrest – my record would be wiped clean. No probation officer. No criminal record. No nothing.

I was willing to plead no contest, because I believed this was the proper plea. My understanding of Non-violent political theory was that you disobeyed a law because you believed it to be unjust. You did not then go into court and deny your guilt. You pled guilty or, in my case, no contest. So everybody was happy: My uncle and parents because I wasn’t endangering my future; and me, because I was upholding my principles. It was what we would call today a win-win situation.

From the time I had arrived at Berkeley two years earlier, I was pulled in two directions: toward, on the one hand, experiencing and changing the world, and on the other, knowing more about and serving God. I did not yet understand that these two orientations could support and be reconciled with one another. And I suppose that in having these two impulses, I was not – even among Berkeley politicos – as alone as I imagined.

A mural depicts Mario Savio, key member in the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, delivering a speech at UC Berkeley. Credit: Creative Commons/ Caleb Haley.

As I learned more about the Non-violent movement, I came to see it manifesting the intersection between spirituality and politics. The Free Speech Movement sit-in was supposed to be a Non-violent protest. I felt – no doubt self-righteously but also probably correctly – that the FSM was using Non-violence as a political tactic, having nothing to do with spirituality. Perhaps there were others among my fellow FSMers who felt the same, but at the time I didn’t think so.

So I sat there on the floor, stewing in my own juices. I had read – and so much of my knowledge of the world came from reading – that Gandhi required a period of intense spiritual preparation from his Non-violent warriors. Martin Luther King – like Gandhi a deeply spiritual man – was forced by the stress of circumstance to require less formal preparation from his Civil Rights demonstrators. We, in the FSM, it seemed to me, required no preparation at all. But we were happy to call ourselves Non-violent. I sat there on the marble floor mentally shaking my head: They just don’t get it.

I had grown up in secular humanist family. I wanted people like my parents to understand that unless left-wing politics is undergirded with spirituality; it will fail to achieve the goals which it’s many well-meaning advocates so passionately desire. (I still believe that’s true.) As far as I was concerned, my parents were hypocrites, having made compromises with the world. I didn’t understand at that age that almost everybody does. Make compromises, I mean.

After what seemed like days, the police finally arrived, in our case, the Oakland police. Many Oakland policemen, at that time, had been recruited from the South, where cops knew how to deal with Negroes (Of course that was not the word they used.) I sat there in my fluffy pink sweater, and my eyes filled with tears. One of the cops mocked me:

“Go back to the nursery school, where you belong,” he jeered.

I didn’t say anything. I just sat there on the marble floor. The cops ordered us to get up and walk out of the building.

“Move it!” they yelled, when we didn’t respond.

We just continued to sit there. Eventually, they picked us up, and carried us, one at a time, out of the building. For this, we were charged with resisting arrest, the most serious of our so-called crimes. In my case this carrying was gentle enough. I know now, that with some of the other FSMers, the experience was much more physically abusive.

After our arrest, we were segregated by gender. I was placed with a group of other women, who were incarcerated in the gymnasium of a National Guard Armory. Without our brothers, our spirits began to sag. I’ve heard that the principle function of women in the FSM leadership had been to bring coffee to the men who had serious business to conduct. I don’t know through my own observation or experience that this was true, but it certainly may have been. So, once again, I sat on a floor, and waited. Eventually, we were bailed out, en masse, by our abashed professors and fellow students.

When I think about my FSM adventure, it seems to have an aura of glamour about it. But when I actually write about it, I realize that it was anything but glamorous: that, indeed, it involved an interminable amount of waiting. That may be true of a lot of civil disobedience. I wouldn’t know: This was my one and only experience.

I still believe that we were right. I believe that as students at the flagship campus of the California system of public higher education, we had a right to hear speakers across the political spectrum, and to judge for ourselves the value of their words. I believe that we had the right to set up tables at Telegraph and Bancroft and distribute literature of whatever political stripe we chose.

Today, we hear a great deal of talk about the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, and very little about the First. Yet, it is that amendment, defending as it does the rights of free speech and assembly, which is absolutely essential to the life of a democracy. We were idealists, who wanted our country to live up to its purported ideals. To that charge, I am still happy to plead no contest. If that made us criminals, so be it. We were loyal Americans, exercising our right to criticize the nation of which we were citizens, and which we loved.

Finely sculpted essay containing cogent insight and strong message.

I was a psych resident in Herrick which held a disaster exercise on the day of the “people’s park riots” though the rioting was provoked solely by the police and the nat. guard in the interest of inhibiting free speech, as the events later at Kent State so aptly demonstrated. Our focus now on the second amendment, must in some ways acknowledge our fear of losing our rights under the first. As Ms. Hardy acknowledges, it is the “non violence part” which has been forgotten, or worse, ignored in the service of venting anger at the government, that has trampled the spiritual part of our protest into the dust. It is true, sadly, that “violence begats violence” and our rights under the first are lost. It seems as if the dark of violence is gaining ground in the world today, and who is shining the light of non-violence? Peace. Dr. Robert Newport

I was over at San Francisco City College in 64-65. We had some issues with the college about allowing a lot of speech-including students just to speak about conditions outside. I’d tried o get anarchists Ernie Barry and Jeff Poland on campus, they also organized rent strikes, etc. Most of us were working and trying to go to school at the same time, I can’t remember if the school had allowed women to wear slacks and not nylons at the time-i’d gone in and talked to the dean about that at one time. There was a big protest, we organized many students, it took months-the pres. at the time was Conlan. he didn’t like it at all, but all our demands were eventually met. don’t know what’s going on there now. In ’66 I went to San Francisco Art Institute. The students organized a big protest out in the atrium, first supporting a grad student who hadn’t paid his monthly tuition on the day demanded. There was something that if one didn’t pay at the right itime, you could be liable for that month and also the whole semester as well.$$. There was a lot of protest about the financial policies, and people were not happy with the new arrangements-in which the art school was now not so much an art training academy as another university, with like required classes-having nothing to do with art-making. Result-Project Artaud and other like places where artists cooperate to be artist. I hear that a famous muralist went to SFAI, and the powers there hassled her about the ‘requirements’.

One of the problems now is that history is being re-written for Wall St. and people who are brainwashed or who are the wannabees of like scum.