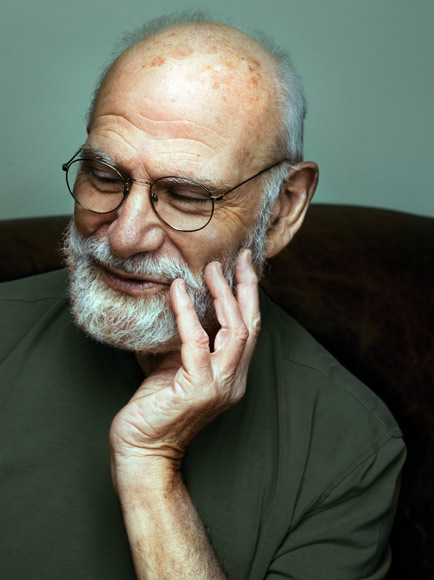

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The strain was beginning to show. In a smart London hotel suite, surrounded by a chaos of scattered papers, books, empty whisky glasses, Oliver Sacks was decidedly grumpy. No, more than grumpy: he was angry. January 1990: at the end of a week immersed in round-the-clock interviews about his latest book (Seeing Visions, on deafness), Sacks was faced with yet another publicity chore. I felt I was sitting with a man ready to explode.

He’d already spoken to the Jewish press in the west of England, he told me – I’d been commissioned by the Jewish Chronicle to interview him – and he didn’t know why he needed to speak to me. Neither did I. Maybe my helplessness touched him. Or maybe when I said I wasn’t a journalist, but a therapist and rabbi, something in him shifted, mellowed.

He spoke about (I asked about) his formative years – until the age of six he existed within the security of a north London medical family, his father a Yiddish-speaking doctor in Whitechapel (east London), his mother the first Jewish woman elected to be a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. In this Orthodox household “the Sabbath bride was welcomed in”, he said, “I always felt there was a sense of mystery when I saw my mother’s hands hovering about the candles.”

War came, and evacuation to boarding-school, which “cut me off from family and community and Judaism”. This “awful traumatic period in the countryside between ’39 and ’43” seemed in retrospect – this is a man who chose from the mid-1960s to spend 50 years of his life in twice-weekly psychoanalysis – to have generated in Sacks a great capacity for empathy with his patients, particularly those “subjected to forces and deprivations which threaten to overwhelm them. I think I had something of this myself…’evacuation syndrome’ is second only to ‘concentration camp syndrome’ in its capacity for severe psychic damage.”

After the War, “friends and science were crucial for holding me together. I developed a strong passion for science – which seemed to be in a realm above human caprice and uncertainty.

The scientist who kept, he said, a Bible by his bedside peered at me through his gold-rimmed spectacles and smiled, then shrugged half-apologetically: “I – alas! – am the only member of my family who is illiterate in things Jewish…I don’t feel particularly Jewish, or English, or white, or particularly anything else.” I didn’t comment that this self-disclosure about Jewishness sounded conventionally, familiarly, ‘Jewish’ to me. Yet something about his sudden diffidence didn’t ring quite true.

Looking back, I wonder if it was what he wasn’t speaking about that gave rise in me to that doubt: his homosexuality, such an important dimension of his emotional life but in 1990 not yet acknowledged publicly. In his recent memoir On The Move: A Life Sacks recounts how his mother reacted when, aged 18, he confessed that he preferred boys: “You are an abomination. I wish you had never been born.” For the rest of her days she never again mentioned his sexual orientation. Nevertheless – or maybe one can say ‘therefore’ – “her words haunted me for much of my life”, he writes.

Sacks’s reputation as a writer-neurologist was built on a series of books, case-histories, combining careful observation, extraordinary empathy and a translucent prose style: Awakenings – on patients ‘awakened’ by drug treatment from decades-long trance states, his autobiographical A Leg To Stand On, chronicling the psychological after-effects of a broken leg; and The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat, where, like Freud, he transformed clinical descriptions into literary art. All these texts explored the margins of human experience: they were “narratives of survival and transcendence of the soul battling against terrible odds. The imprisoned and pressurised – but battling and triumphing – soul is something which inspires me”, he said, “and makes it possible for me to work in the depths of chronic hospitals.”

But this sense of a man who knew about the soul’s inner struggle was also palpable in the room: “I feel I have to struggle to survive myself” he said, disarmingly, “I’m conscious of…” – and he hesitated – “…terrible forces in me…Clinically, personally, politically, one is confronted with monstrous impulses and destructive forces, and it is very dangerous to underestimate their strength”. The history of the 20th century – and the on-going barbarism in the daily news – is testimony to the sobering reality of Sacks’s words.

But his writings didn’t venture into the overtly political. His life’s work – his gift – was to find a way of entering into his patients’ inner worlds not as a detached clinician but as a fellow human being, and to find a form of words to describe the experiences being suffered or endured or just lived with. His patients weren’t interchangeable ‘patients’ – they were people, no two alike, even though a diagnosis might make them seem to be suffering from the same condition. “Medicine is in danger of treating the patient as an ‘it’ rather than a ‘Thou’”, he told me: Sacks was the Martin Buber of the medical world. He wasn’t interested in a patient’s diagnostic ‘conditions’ but in the unique lived experience of each person and the core of creative potential that each particular person might be able to unearth within themselves.

The human brain – “this three pounds of jelly”, he once described it – was a source of endless wonder to Sacks. And as I sat there with him on a wet January morning in a swanky London hotel room, watching him impatiently fingering his dazzling striped braces worn over a T-shirt proclaiming (in Norwegian) support for Tourette Syndrome sufferers, Sacks suddenly burst out laughing: “Being alive and being conscious is fucking extraordinary”, he said, and this sensitive and passionate and spiritually alert Jewish doctor seemed to relax into his deeper self: “The central feeling for me, and the motivating feeling, is wonder and the sense of the mysterious. Beyond all the problems there’s always a sense of the immeasurable and the immense. The sense and concept of eternity is something which I sometimes have, and often need – and which all of us need. The spirit is undervalued and forgotten in a way that impoverishes life. The need for praise and gratitude and thanksgiving and appreciation seems to me central. I don’t know whom to give thanks to, but I have an impulse to praise.”

As my time with Oliver Sacks drew to a close he found himself reminiscing about childhood: “A feeling of peace, and relief from the quotidian and the daily, would come on Friday evening. I used to have a vision that the Sabbath was not simply terrestrial, but a cosmic event, that the universe rested and paused every so often. The feeling of peace is essentially a religious one – certainly something which is easy to lose – especially when you have twelve interviews a day…”

Sacks was a humanist endowed with a profound religious sensibility. A secular Jewish mystic. His gift was to find a way of making real, in his writing and his clinical work, what it means that human beings are created ‘in the image of God’ (b’zelem Elohim: Genesis 1:27).

Zichrono livracha – may his memory be a blessing.

—

Rabbi Howard Cooper is a British psychoanalytic psychotherapist in private practice, Director of Spiritual Development at Finchley Reform Synagogue, London, and blogs on Jewish issues and current affairs at www.howardcoopersblog.blogspot.com

Thank you for this touching article about such a wonderful man we will miss every day.

He helped still believe in humanity (so difficult to find these days in a world that seems to have lost all sens of humanity!)

All the best and thank you once more

Ana