Last week I wrote about how we can approach individuals when we want to see change in their behavior. I ended with an exploration of relating to children, which can serve as a possible entryway into exploring change within organizations, the original context that started me thinking about this rich and difficult topic. The similarity between the context of organizations and the context of parenting has been striking to me. In particular, in both settings the power difference is vivid and clear, as is the expectation, common to both relationships, that the one with power is the one who knows what’s best.

Supporting Culture Change within Organizations

My recent work with organizations has been the direct catalyst of this entire line of inquiry. My intense inner engagement with the general question of how change comes about was precipitated by some challenging experiences I’ve had with one client recently. Specifically, I noticed that within one organization, where my charge is quite limited, the work I am doing is making more ripples, whereas in another organization, where I have been doing a much larger project, there have been significant obstacles.

In both cases I am engaged with the CEO, the leadership team, and some other teams within the organization. In one case, the smaller project, I came in knowing that I was going to work within the existing paradigm of power. This is a service organization that has a fair amount of bureaucracy and established procedures for everything they do. When I meet with the leadership team, I am following their lead in terms of what they want, my only limit being my personal integrity, which has on occasion led me to express what I see and want to see happen in ways that have earned me a reputation within that organization of someone who is willing to speak truth. Within these constraints, I have managed to shift the internal dynamics within the teams I work with such that the administrative staff now participates in meetings rather than just observing and recording meeting notes. I have supported the creation of conditions that now allow for more conversation and trust within the leadership team, and I hear from the team that they are able to apply in other circumstances what they learn in the meetings I facilitate. There is more trust, and more collaboration is beginning, laterally and vertically. It’s a slow process, and yet I often leave my meetings almost elated, whether with one of the teams I support or with the CEO. I see change happening.

In both cases I am engaged with the CEO, the leadership team, and some other teams within the organization. In one case, the smaller project, I came in knowing that I was going to work within the existing paradigm of power. This is a service organization that has a fair amount of bureaucracy and established procedures for everything they do. When I meet with the leadership team, I am following their lead in terms of what they want, my only limit being my personal integrity, which has on occasion led me to express what I see and want to see happen in ways that have earned me a reputation within that organization of someone who is willing to speak truth. Within these constraints, I have managed to shift the internal dynamics within the teams I work with such that the administrative staff now participates in meetings rather than just observing and recording meeting notes. I have supported the creation of conditions that now allow for more conversation and trust within the leadership team, and I hear from the team that they are able to apply in other circumstances what they learn in the meetings I facilitate. There is more trust, and more collaboration is beginning, laterally and vertically. It’s a slow process, and yet I often leave my meetings almost elated, whether with one of the teams I support or with the CEO. I see change happening.

The larger project, on the other hand, began with the promise of changing paradigms and creating a fundamental culture shift within the organization. Jonathan (his name and some of the details below are changed for anonymity) is excited about sustainability, and has a successful small and growing manufacturing company in the Bay Area that produces environmentally friendly clothing products. Jonathan wants his company to be a model in all possible ways, both in terms of the products and in terms of its values and internal operations. In fact, I think he believes it already is so.

When I started working with his company, I set out to note and offer him feedback about all the ways in which his behavior affects others adversely, as well as ways in which structures and decision-making processes were not aligned with the vision I thought he and I shared. I was eager and excited, and kept inviting him to stretch more and more. In retrospect, I didn’t offer him sufficient empathy for the enormous challenge that any of us would face when informed that, despite our positive image of ourselves, others experience us differently. Also, I underestimated how much of an effort it would be for him or anyone in his position to actually align behavior with values in this arena. I didn’t see how much of an identity change it would be to fully embrace the collaborative paradigm; how much all of us, and Jonathan in particular, are still habituated to the idea that a CEO simply gets his way.

The result is that Jonathan lost his trust in me, and the project is now teetering. Others in the company are still very interested in working with me, and yet I am not confident that I would know how to support them without Jonathan’s full buy-in for the work.

Here’s how this ties to my earlier thoughts (see last week’s entry) about the three conditions for change. Jonathan doesn’t have any perceived need, in the moment, that would be met by continuing to engage with my feedback and coaching. From his perspective, he is satisfied with how he is running the company. Since, in addition, I don’t have the resources to stop those elements of his behavior that concern me, and since we are not in trusting dialogue, I simply don’t see how change would come to happen in this company. Hence the paradox: the service agency, with a small mandate, is making more headway toward collaboration than Jonathan’s company with the explicit commitment to being an innovative workplace.

Change from Above, Change from Below

|

| When you put “CEO” in Google Image Search |

One of my clear aspirations, about which I have not been particularly secretive, is to support the emergence of human societies that work for all who live in them. As someone interested in contributing to radical change in our social structures, it’s often been attractive to focus on people in positions of power. Because people in positions of power have more resources at their disposal, they have more efficacy as individual actors to make things happen. If a CEO like Jonathan embraces collaboration, for example, he (usually) or she can simply decide and put into place new structures that implement collaborative practices. If an individual receptionist gets excited about collaboration, on the other hand, she (usually) or he could only bring about more collaboration through modeling collaboration, through ongoing dialogue, or through bringing people together and inspiring them. There is no direct way that the receptionist can do what the CEO can do with the same degree of efficacy.

|

| When you put “receptionist” |

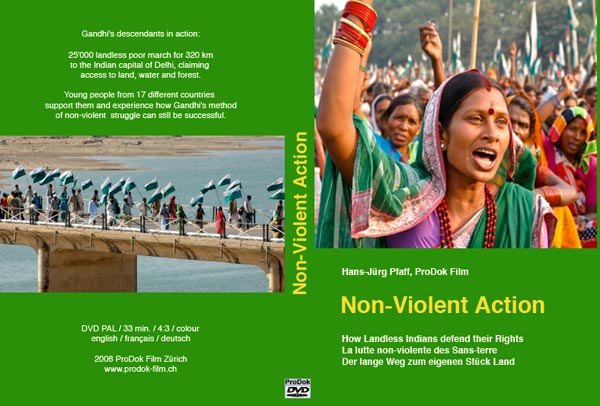

When Gandhi took on the British rule of India, he mobilized millions of people with little access to resources who, together, managed to overcome their fear, including fear for their lives, and put so much joint pressure on the system that the British could not continue to tolerate the cost of their occupation of India, and finally left. What was it that made this campaign nonviolent, and is there anything that Jonathan’s employees can learn from it?

First and foremost, Gandhi’s engagement in politics stemmed directly from his interest in the roots of nonviolence, the love of all beings. In his own words: “To see the universal and all-pervading spirit of Truth face to face one must be able to love the meanest of creation as oneself. And a man who aspires after that cannot afford to keep out of any field of life. That is why my devotion to Truth has drawn me into politics…” (Quoted in Eknath Easwaran, Gandhi the Man, Nilgiri Press, 2011 edition).

Indeed, throughout the entire set of campaigns that Gandhi engaged in, including when he was in prison for many months at a time, he continued to be available to dialogue with the British rulers, and to offer his human caring to them. Hard as this may be to believe, this is highly documented, and a number of quotes to this effect can be found in my article “Gandhian Principles for Everyday Living”.

So far, Jonathan’s employees have not been able to overcome their fear, come together strongly enough, or maintain a loving stance toward Jonathan. If they can articulate a clear vision to Jonathan, including their conviction of how it would meet his needs better than his current way of doing business, they will be stepping into Gandhi’s and King’s loving framework. If they can put in a concerted effort to stand up to him lovingly, that would be the equivalent of mass nonviolent resistance within an organization.

Clearly, this is not easy to orchestrate. It would be so much easier to create the change if the people who run our organizations, small and large, embraced the interest in true collaboration. Sometimes I am so challenged to grasp how and why they can continue to do what they are doing knowing that so many are unhappy about their choices. What makes it so hard?

In this context, the repeated finding that people with more access to resources are likely to be less empathic seems painfully relevant. It makes sense to me that they would have to have less access to empathy in order to do what they do, since without this partial loss of empathy I can’t see how they would agree to get things to happen at cost to others or why Jonathan, and so many other people in positions of power within organizations (probably myself included), imagine that there is more alignment with their visions and wishes than there may be. Disagreements with the person in power are suppressed, and the true cost of his or her actions is either not known to people like Jonathan or tolerated by them because their hearts are at least partially closed to others. What it is that contributes to such partial loss of empathy is not something I can explore in this already lengthy blog entry. I will only say that somewhere in my heart I continue to believe that this loss is reversible, or I wouldn’t be doing what I am doing.

In this context, the repeated finding that people with more access to resources are likely to be less empathic seems painfully relevant. It makes sense to me that they would have to have less access to empathy in order to do what they do, since without this partial loss of empathy I can’t see how they would agree to get things to happen at cost to others or why Jonathan, and so many other people in positions of power within organizations (probably myself included), imagine that there is more alignment with their visions and wishes than there may be. Disagreements with the person in power are suppressed, and the true cost of his or her actions is either not known to people like Jonathan or tolerated by them because their hearts are at least partially closed to others. What it is that contributes to such partial loss of empathy is not something I can explore in this already lengthy blog entry. I will only say that somewhere in my heart I continue to believe that this loss is reversible, or I wouldn’t be doing what I am doing.

Barebones Implications for Social-Structural Change

So what of our efforts, personal and collective, at creating large scale change in our structures? If we want such change to come about, I would venture to say that the same conditions would apply: either someone, or more than one, in a position of power will decide to create such changes because they see that it will benefit them; or we find a way, through dialogue, to open their hearts to the misery of billions and the dire conditions of the planet as a whole, and they agree out of care to wake up to what we see happening; or we will find a way to mobilize enough resources, enough people, and enough love to make it intolerable for them to continue to engage in their current practices.

Within the context of North America, I feel quite discouraged. In social change circles I see so much derision and hatred instead of love and an aim to find ways that work for all. I see so many people outside those circles who continue, on some fundamental level, to see what’s happening as somehow working, or who are so dependent on the current system that even though they know it’s not working, they are too afraid to challenge it or lack imagination about how. I see so many of us habituated to the material comforts that are the carrot given to us by the existing system. I see so few of us able to engage meaningfully with others to create true solidarity and to transcend fear and build community. And, sadly, I see so many in positions of power who are committed to continuing to enjoy the fruits of their access to resources, regardless of how their actions affect others, and without true willingness for dialogue.

Outside the dominant culture in the US, however, I see a lot of reason to feel optimistic. In the last few decades, dictatorial regimes have been dismantled at a growing rate, mostly through nonviolent means (recent horrific events in Syria notwithstanding). It appears to me, in my rather uninformed intuition, that more people are aware that things are simply not working any more, and in the long run will not work for anyone.

So how are we going to create change in the US? I don’t know. I only see that in the absence of sufficient numbers of people, the standard actions that social activists engage in will continue to irritate the powers that be without creating any true incentive for them to engage meaningfully. My current strategy, then, is to continue to look for the people who feel ready. I know I am not a movement builder nor a community organizer. I hope that some of the people who are drawn to work with me will be. It is one way that I can imagine my efforts resulting in true change.