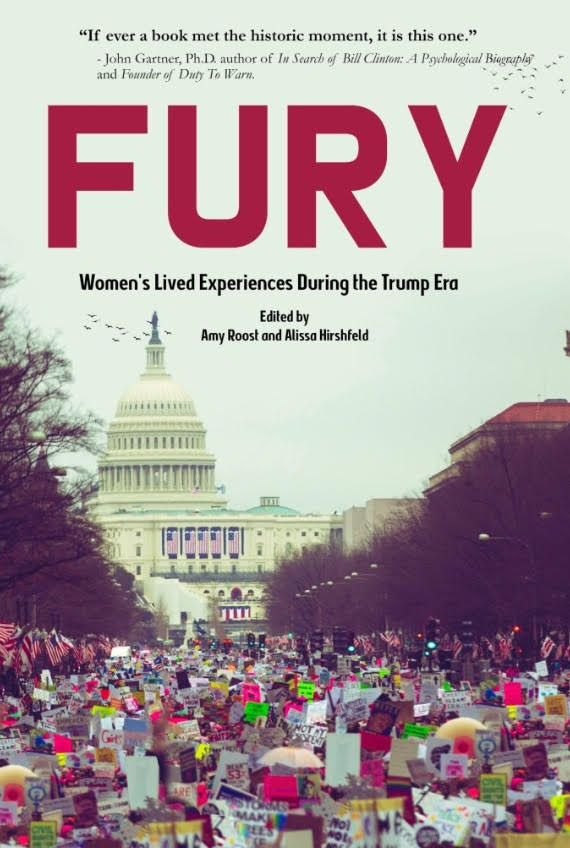

As soon as I moved out of the shock phase after the election results in 2016, I fully entered into anger. A tangential activist in the past, who supported others from the sidelines and only entered the fray occasionally, I moved fully into activism where I thought I could make a difference. As a psychotherapist, I became a local leader in the Duty to Warn movement, which began as an effort by a single psychologist to warn of the dangers Trump poses to the public’s mental health and well-being. We circulated a petition to invoke the 25th amendment, which was ultimately signed by 70,000 mental health practitioners and which led to town halls across the country, consultations by psychotherapists with congress people (I myself talked with Congresswoman Jackie Speier), books, media appearances, and a film (#UNFIT). I facilitated workshops with Dr. Peter Dunlap on how politics influence our personal psychology. I began to blog (citizentherapist.wordpress.com) about this intersection of the political and the psychological, including the impact of our current political situation on our psychological wellbeing, individually and collectively (notions very familiar to the Tikkun community, but still somewhat controversial for most of my mental health colleagues). Attention to my blog led to my collaboration with journalist Amy Roost on the publication of “Fury: Women’s Lived Experiences During the Trump Era,” which is being released by Regal House Publishing today, March 20, 2020.

“Fury,” is an emotionally-charged collection of essays by a diverse group of 38 women. We consciously sought out contributions from women of different ethnicities, cultures, religious and spiritual backgrounds, sexual orientations, and ages. The essays chart the types of upheavals that President Trump has caused in these women’s inner lives, families, relationships, and work lives. Each essay richly portrays it’s author’s emotional experience, from their unique vantage point, during and after the 2016 election. The essays describe what these parents, teachers, mental health professionals, authors, and activists went through trying to make sense of, find hope, and find ways to fight for what they believe in.

This book serves as a historical document, describing first-hand accounts during an alarming moment in American history. As such, readers will identify with one or more of their stories, gain empathy by being able to enter the shoes of someone different from themselves, and hopefully be inspired in their own activist efforts.

There are several themes that run through the essays, among them how Trumpism is affecting women from minority groups, how difficult it is to explain his behavior to our children, and how the actions of a malignantly narcissistic man who objectifies and assaults women are affecting us all.

While we solicited essays from a broad spectrum of women, as it happens a sizable minority of the pieces are by Jewish women. We write from the perspective of Jews who once felt safe in American and could not conceive of a rise of Nazi sentiment.

In her essay “How I’m teaching My Jewish Daughters About Donald Trump,” Lea Grover, a mother of young children, writes of taking her children to Hebrew school the day after the Women’s March:

“[I]n the morning we woke again to go to Hebrew School. Only it wasn’t Hebrew School as usual. Over the previous weeks, dozens of Jewish community centers in the United States had been targeted with bomb threats. Hate crimes against Jewish people had risen, in some places by 110 percent, in the ten weeks since election night. So on Sunday, two days after the inauguration of a man who appointed known anti-Semites to his transition team and cabinet, our synagogue and Hebrew School had a lockdown drill.

“I watched children cower behind couches in the corner of the school library, as silent as they could be, pretending somebody might be coming to kill them. One of the girls had left her book on a seat—she was reading Letters from Rifka, a childhood favorite of mine—a story about a girl fleeing religious persecution in Russia in the years leading up to the Holocaust. On the shelf behind that seat sat a copy of The Diary of Anne Frank.”

Dawn Marlan, who grew up in the Squirrel Hill community of Pittsburgh writes in her essay “Hauntings”:

“I am sitting in Temple Beth Israel in Eugene, Oregon, and . . . the new rabbi mentions Pittsburgh. The tragedy that happened this morning in Pittsburgh. My heart stops beating.

“It all comes out when I’m standing in the social hall—the blood- bath in Squirrel Hill, the man shouting, ‘All Jews must die,’ as he sprays the synagogue with bullets. I remember that my father is at a conference in Denver. My stepmother and brother would not be in synagogue. But they might be “up-street” running errands. I try to calculate whether they are at a safe enough distance from the danger. . .

“I read the names of the victims and for a minute I think, no one I know. I read the list again and linger over two names, hauntingly familiar, as I fight through the haze of thirty-five years. I scour my feed, post after post from Pittsburgh. Everyone I know from Squirrel Hill is in mourning, and it is confirmed, two of the victims are David and Cecil Rosenthal, who used to hang out at the JCC, and, I’m pretty sure, were in the arts and crafts class and on the trip to Philly. I recognize them now in the pictures, the faces of the young men shining through the faces of middle-aged men, embraced by a community that does not punish difference.”

Some essays by women of color speak to the fact that the racism that is so glaring now to White Americans came as no surprise to them. In “It’s Been There,” Elena Perez writes:

“I can’t blame Dad for laughing at the outrage expressed over the racism we read about in the news today. “Did you think it would just go away?” Without waiting for our reply he’d retort, “Hell no!” It just went underground.

“So let’s be honest for a change. Stop pointing, appalled, at the blatant sexism, heterosexism, racism, or bias of whatever form that has risen up alongside—even supported by—the Trump administration.

“It’s been there.

“Maybe you haven’t noticed it if you haven’t experienced it, if you haven’t recognized your own role in perpetuating it, intentionally or otherwise. But it’s been there. It’s what got Trump elected in the first place; it’s why politicians treated our forty-fourth president with blatant disrespect; it’s why Middle Easterners posed as Latinos soon after September 11.”

In “Love in the Time of Trump (A Letter to My Beloved),” Simran Sethi writes of the struggles of being in an inter-racial relationship with a White man of privilege. After two years of shared political activism and continual ups and downs in their relationship, the relationship cannot sustain the tension of their differences. Her lover writes to her, poignantly, “They got exactly what they wanted. They built a wall between us.”

Several essays by mothers highlight how they are trying to teach their children the values of empathy, compassion, and integrity, in contradistinction to what our president models, as well as how these moms are modeling to them activism.

In “Children Question the Bully’s Right to the Presidential Seat,” Cassandra Lane, an African American mother, writes of trying to explain to her young son, who gets bullied for toe-walking and stuttering, how a bully could possibly have been elected president:

“On election night, Solomon’s homework assignment was to watch the results, but ultimately, his body gave way and he fell asleep, like millions of children across this country. Just before succumbing to his dream state, though, he saw the numbers, he saw that Trump was leading the Electoral College, and he tried his hardest to differentiate each state’s popular vote numbers from the overall national ones. He went to bed confident that Trump would not win, because in the stories, the bully always loses in the end. The next morning, Marcus and I tried to normalize breakfast: oatmeal with cream and butter, toast, tea. Marcus turned on the TV, but placed it on mute. Solomon kept asking us: “How could someone like Trump get elected to be president?”

Psychological distress and trauma are prominent themes that run through many of the pieces, including my own. Several essays by mental health professionals highlight the ways Trump’s malignant narcissism is triggering dysregulation in women who have narcissistic partners and fathers, as well as how women with histories of sexual trauma have been impacted by our predator-in-chief, as well as by the Kavanaugh hearings and the #MeToo movement. In her essay, “Trauma in the Age of Trump,” Dr. Lorraine Camenzuli explains the neurobiology of the traumatic reactions that so many of us are experiencing.

“Fury” aims to help us see the experiences that connect us, and ultimately to engender empathy among its readers. As I write in “The Challenges of Being a Psychotherapist in the Age of Trump”:

“I never imagined that empathy would become a political act, but—alas!—it has. People on opposite sides of the political divide, as well as people of different cultural backgrounds and faiths, seem unwilling and sometimes unable to empathize with different perspectives. But when we listen deeply to one another’s stories— meaning we practice seeing things from another’s perspective while silencing the voice inside us that wants to disagree or tell our own side—we learn that we all want the same basic things: a good life for ourselves and our families, good health, an adequate income to provide for our needs, a community to belong to, and a sense of meaning and purpose. When I teach clients to feel compassion for themselves and to empathize with their partners and family members, I hope that I am also providing them with the skills to empathize with their fellow human beings, whomever they may be. This may be the most important political action I can take in this period in the country’s history.”

My hope is that this book will help readers in taking a much-needed step in that direction.

Please visit Regal House, an independent, women-run publishing company to purchase Fury: Women’s Lived Experiences During the Trump Era.