WHEN MY FATHER WAKES UP

on that first sweltering night

of that first scalding summer

soaked in sweat like my mother

when she suffered those terrible

hot flashes 40 years ago,

he stumbles out of bed

and lumbers to the archaic air

conditioner, fumbling for the right

button to bring it back to life

with a wheeze and a groan and

a thump. Next he shuffles across

the faded carpet, slides between

the worn sheets, and lifts the torn

blanket to cover my mother

who will surely grow stiff

from the frigid air blowing

between them as she had

for more than sixty years.

Who could blame him

for forgetting she had left

him and was now slumbering

on the other side of town

wrapped in a shroud beneath

the stony, stubborn ground?

How he missed

her old cold

shoulder

YES WE HAVE NO

bananas.” My father croons

off key as we stroll

through the supermarket.

“Shall we get some?” he asks,

a standing joke between us.

My father hates bananas,

peaches, plums, mangoes

anything mushy makes him

shudder in disgust.

“Remember that time

I baked you banana bread?”

I stop our cart to ask.

“You loved it until I told you

what it was, remember?”

“Really?” my father says.

“Impossible.” he backs away

from the bananas as though

they mean him harm.

“I don’t remember.”

“Sure you do,” I insist.

“I put three pieces on a plate

and you ate them all.

It was the summer before

I went off to college.”

My father steers clear

of the bananas and pushes

the cart towards the deli

“Where’d you go to college again?”

he asks, placing a package

of rugelach into the cart.

“Vermont,” I say, removing

the rugelach which is bad

for his diabetes. “Don’t you

remember? We drove up

and stopped for lunch

at that diner in Montpelier,

and the one woman working

there was seating people,

taking orders, cooking,

running the register

and Mom felt so sorry

for her, she offered

to leap over the counter

and lend a hand, remember?”

At this my father brightens.

“Ah, your mother,” he says.

“She could have done it.

She could do anything.”

“Almost anything,” I correct him.

“There was one thing

she could never do.”

I reach for a bag of whole

wheat bagels. “What’s that?”

my father asks, genuinely curious.

“She could never get you

to eat a banana.”

“That’s true.” My father’s chortle

dies in his throat.

“I would eat every banana

in the world

just to see her one more time,”

he says, and we both fall

silent, make fists

around the handle

of our grocery cart

and together we push on.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

MY MOTHER IS AT THE BRIDGE

table with Loretta, Gert

and Pearl, when my father

finds his way to heaven.

“Sit down, dear,” she says

patting a chair beside her

barely looking up from the hand

she’s been dealt. “The game is

almost through.” But my father is

too overcome to sit. He stands

and stares at his beloved, free

of wheelchair and oxygen tank

happily puffing away

on a Chesterfield King

held between two perfectly

manicured fingers, sipping

a cup of Instant Maxwell

House, leaving a bright red

lip print on the white china cup

her hair the lovely chestnut brown

it was the day they met,

her face free of worry

lines, the diamond pendant

he bought her on their first trip

to Europe glittering

against her ivory throat.

She looks like the star

of an old black-and-white movie

who would never give him

the time of day but somehow

spent 63 years by his side.

“I missed you,” my father

tells my mother, leaning down

to kiss her offered cheek.

“Of course you did,”

says my mother, who always

knows everything.

She plays her cards

right, and after Loretta and Pearl

and Gert fold, she stands to let

my father take her in his arms

and in their heavenly bodies

they dance.

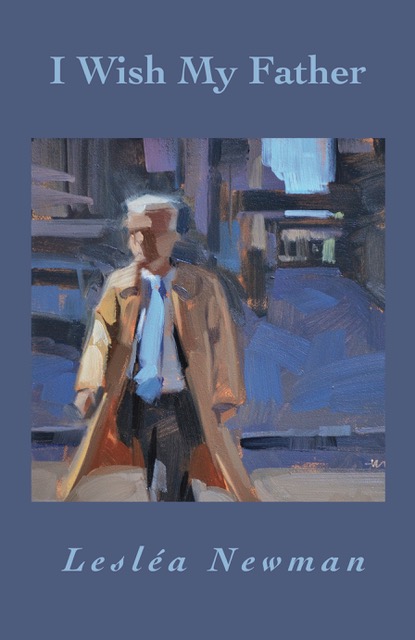

“When My Father Wakes Up,” “Yes We Have No,” and “My Mother Is At The Bridge” copyright ©2021 Lesléa Newman from I Wish My Father (Headmistress Press, Sequim, WA). Used by permission of the author.