[Editor’s note: Thomas Merton OCSO was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist, and scholar of comparative religion. He was held in high esteem by my mentor at the Jewish Theological Seminary, Abraham Joshua Heschel, who introduced me to his writings. December 2018 marks the 50th anniversary of Merton’s death.–Rabbi Michael Lerner rabbilerner.tikkun@gmail.com]

In 1802, sensing that his great nation was heading in the wrong direction, the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850) wrote the following poem to his illustrious poetic predecessor, John Milton (1608-1674), author of Paradise Lost, one of the seminal texts in Western literature:

LONDON, 1802

Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour:

England hath need of thee: she is a fen

Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen,

Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower,

Have forfeited their ancient English dower

Of inward happiness. We are selfish men;

Oh! raise us up, return to us again;

And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power.

Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart:

Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea:

Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free,

So didst thou travel on life’s common way,

In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart

The lowliest duties on herself did lay.

Today, a similar poem could be written invoking Thomas Merton, who died under mysterious circumstances half a century ago this month on December 10, 1968 while attending a religious conference outside Bangkok, Thailand. But instead of complaining that England had drifted too far from “manners and virtue,” the modern poet would say that we need Merton for his outspokenness during the 1960s against violence and unjust wars, religious and political zealotry, despotism and isolationism, racism, intolerance and inequality, and for his advocacy for environmental protection and nuclear disarmament as the only solution to diminish the threat of annihilation by reckless world leaders itching to press the button. It has been said that Merton was “America’s conscience.” Merton understood that governments and nations tend to be less guided by conscience and a sense of responsibility than are individuals, and that this lack of conscience is the cause of wars and every kind of oppression and the root of pain, bitterness, and suffering.

It is safe to say that in the ensuing half century, America has changed very little.

Certainly, Thomas Merton would be astonished by our flat screen high-definition televisions, ubiquitous cell phones, tablets and laptops, the Internet, self-driving cars, the absence of wristwatches and hats, and our missions to Mars and the very edges of our solar system, not to mention by the price of a movie theatre ticket and popcorn and the fact that people are still watching re-runs of Gilligan’s Island. But even in the 1960s, Merton understood that advances in technology—what we call progress—does not imply progress of humanity’s nature or of the human spirit. Having faster laptops or bullet trains does not make us better human beings. Merton understood that advances in technology, especially in areas like aviation and communication, are frequently the fruit of war, of devising more effective means of destruction. In his letters, Merton sarcastically mocked our technocracy.

Although it’s been fifty years since Merton’s untimely death, America remains largely unchanged in many respects. Despite the Civil Rights Movement that Merton and his interfaith cleric friends Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel supported, racism prevails in America, the nation whose most revered founding document declares that “all men are created equal.” He would be astonished by America’s rampant hate of “The Other,” whether it is people of different race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, national origin, or religious affiliation. According to a recent study compiled by SAALT, since the 2016 presidential election, hate violence against people of other religions has increased 64%, with a marked increase in violence against Muslim Americans and Jews, including wanton vandalism of Jewish cemeteries. The Anti-Defamation League recently reported that incidents of anti-Semitism are up 57% since the election, the largest increase since they began collecting data in 1979. Merton would be absolutely horrified by the recent mass-shooting at a Jewish synagogue in Pittsburgh. More than anyone else in the mid-twentieth century, Merton was a bridge-builder between faiths, encouraging interfaith dialogue, exploration, and tolerance.

Thomas Merton was one of the architects of nonviolent anti-war protests in the 60s—along with fellow priests Daniel and Philip Berrigan, Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, and Martin Luther King. In fact, Merton and King had planned a retreat at Merton’s hermitage to discuss Civil Rights and the war, but King was assassinated weeks before the meeting. If he were alive today, Merton would look on America’s unjust wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the quagmire they plunged America into as if he were seeing the reflection of the Vietnam War in some terrible mirror. Hadn’t America learned anything from Vietnam?

Martin Luther King Jr at Civil Rights March in Washington, DC. Image courtesy of Wikimedia.

With America’s war in Vietnam still raging and the Cold War in full swing, Merton warned that no country should unjustly oppress other countries or meddle in their affairs” (Seeds of Destruction, 167). Yet, half a century since his and Martin Luther King Jr.’s passing, Merton would be dismayed to see that America still does the same things, using expressions like “National Security” and “National Interest” to rationalize our actions abroad. He would surely despise the fact that military expenditure devours a greater proportion of America’s budget than at any time in history—even though we are not at war with anyone. He would abhor the notion espoused by so many Americans that we need to stockpile ever more nuclear warheads and that there needs to be more guns strapped on the hips of citizens and in places of worship and public schools. Hadn’t America’s television obsession with gun-slinging westerns mostly come to an end in his lifetime? He would find it incredible that America already has more guns per capita than any other country on earth, and yet, astonishingly, no other country has as many mass shootings as America . . . not even close. In 2018 alone, there were 307 mass shooting incidents in 311 days. That’s almost a mass shooting every day (USA Today, Nov. 9, 2018, p.1A).

Thomas Merton lived during the height of the Cold War and witnessed the most severe stand-offs between the United States and the Soviet Union, including the Cuban Missile Crisis, the world’s closest brush with all-out nuclear war. He lived through the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He corresponded frequently with Bobby Kennedy’s wife, Ethel, to better understand JFK’s and his brother’s position on nuclear stockpiling, and ostensibly to influence Bobby through his wife. In the mid-1960s, Merton wrote in a letter: “That is why we must not be deceived by the giants and by their thunderous denunciations of one another and their mutual preparations for mutual destruction. The fact that they are powerful does not mean they are sane, and the fact that they speak with intense conviction does not mean they speak the truth.” If he were alive today, Merton would see little difference between the relationship of America and Russia then and now, only that other nations like China and North Korea have been added to the growing list of “giants” with nuclear arsenals threatening to blow each other up, even posting simulated videos of potential future nuclear strikes. Needless to say, Merton would be shocked by our current president’s haphazard comments, “I like nukes. What’s wrong with using nuclear weapons?” and by his blustering phallic statement that his nuclear button is bigger than his enemy’s nuclear button.

The world is weary of war.

Presaging America’s 2016 presidential election by more than fifty years, Merton remarked how mass media could be an instrument for disinformation and for marginalizing America’s socioeconomic victims and subverting democracy. In a letter, Merton portended the influence of present day media monopolies: “[We] must be seriously concerned with the ruthlessness and indifference to ruthlessness that are possible in an advanced society when the major means of mass communication are monopolized by a small group representing similar economic, political, and social interests.” Numerous popular alt-right news organizations purposefully sow disinformation in an effort to achieve its political agenda with absolutely no regard for truth or its enduring effects on democracy. Daily, these television and radio hosts proclaim their deceits straight-faced and as cunningly as a fox. President John F. Kennedy famously said that “the strength of a democracy rests on the education of its citizenry.” An un-biased, truth-telling media is part of how citizens are educated about issues. Over the years, I have been told by Catholic priests and bishops, rabbis, and Buddhist monks that “it is never wrong to tell the truth.” Only tyrants attempt to control media and the truth. If Merton were alive today, he would be dismayed to hear a sitting U. S. president—sworn to protect the Constitution—frequently call the free press, protected under the Constitution, “the enemy of the people,” a phrase he lifted from Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler—and threaten that violence will erupt across America if his party doesn’t win elections.

Image of Rachel Carson courtesy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

After publication of Silent Spring in 1962, Merton corresponded with Rachel Carson. Through the 1960s, Merton increasingly advocated for protection of the environment. In the decades since he became a monk at the Abbey of Gethsemani, he had noticed the decreased presence of birds, caused by the widespread use of pesticides like DDT. He would be troubled by America’s (and the world’s) increased rates of pollution. He would be shocked to learn about The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an enormous swirling vortex of floating garbage estimated to be 1.6 million square kilometers (about the size of France) and about similar gyres of garbage clogging oceans around the world. He would be appalled by news of the sheer number of offshore oil spills worldwide (estimated at over 10,000), by images of Canada’s reckless denudation of its northern territory to extract cheap oil from the tar sands, and by the fact that the United States recently pulled out of the Paris Accord—the world’s collective attempt to reduce airborne pollution—only to fulfill a campaign promise and to win votes for re-election.

Hadn’t we learned anything in half a century?

Like his friend Martin Luther King, Jr., Thomas Merton may have been assassinated to silence him, especially his increasingly vocal protests against the Vietnam War. It was

Image of Vietnam War protesters courtesy of Wikimedia.

Merton who convinced King to lend his voice to protesting the war. President Lyndon Johnson once said that he would never lose Vietnam. He said as much to Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge in November of 1963. By 1968, Thomas Merton and Martin Luther King, Jr. had become enormous thorns in Johnson’s side. Merton’s book, Faith and Violence, published while he was away on his fateful Asian journey in the fall of 1968, was extremely critical of America’s unjust war in Southeast Asia. It is a fact that, had he lived, King planned to give a lecture at a church the following day entitled “America is Going to Hell,” in which he was going to denounce the Vietnam War as being unjust and call for the nationwide burning of draft cards in defiance. Merton died mysteriously only a few months later in Thailand, not far from the Vietnam border. He may have known he was going to be killed. Days before his death, Merton wrote a prescient poem in which he presaged his imminent death. Recent books like The Martyrdom of Thomas Merton (Turley & Martin, 2018) convincingly argue that Merton, like Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., was also assassinated, making 1968 an even more terrible year than it already was.

Photo of Rabbi Heschel presenting the Judaism and World Peace Award to Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1965. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia.

One of Merton’s and King’s mutual friends was fellow activist Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, a Reformed Rabbi who saw social activism as the central demand of Judaism. Throughout the 1960s, after studying the writings of the German theologian Meister Eckhart (1260-1328), Merton came to understand that, more than anything, to call oneself Christian means to stand up against violence, inequality, and injustice. Like Rabbi Heschel, Merton came to understand that compassion means justice, and justice demands action, not merely prayer and contemplation.

Having witnessed the rise and fall of despots in Europe—Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin— and the deaths (an estimated 100 million people) and devastation they wreaked on the world, Merton would be appalled by America’s infatuation with fascism as exemplified in the current presidency. Even in the mid-1960s, Merton warned America of electing any leader who is grossly revered as a messiah who has come as a savior like Jesus, only without any of the redeeming, moral qualities of Jesus such as humility, compassion, honesty, forgiveness, inclusion, and nonviolence. Certainly, Merton understood that history bears this out. Hitler cunningly distorted and transformed the Nazi Party into a quasi-religious institution, an idol demanding allegiance and even adoration by its subjects. Akin to some falsehearted politicians today, Hitler gave a speech to the Reichstag on March 23, 1933 in which he declared Christianity as the foundation for the National Socialist Party. “Make Germany Great Again!” was a ubiquitous Nazi slogan. By the late 1930s, any member of German society who did not embrace the Nazi Party or revere Hitler as a God-figure was labelled as “unpatriotic” and a “traitor.”

Image courtesy of Ninian Reid/Flickr.

Sound familiar?

Merton understood that, for the despot who understands that power is an end of itself, usurping the power of religion is a tool to control the masses. Merton, who recognized the importance of the separation between Church and State, would be disheartened to see so many Christian pastors—proclaiming themselves as conservatives or fundamentalists—supporting a tyrant who openly mocks the crippled (whom Jesus healed), is an (alleged) serial adulterer, and who incites divisiveness, malice, racism, intolerance, and violence, publicly encouraging folks to inflict physical harm on anyone who disagrees with him. Hadn’t Jesus once escaped the clutches of a tyrant? Hadn’t Jesus and his family once been refugees seeking asylum from threat of violence? Hadn’t Jesus been inclusive in his ministry? Hadn’t Jesus said to put down the sword, turn the other cheek, and to forgive even our enemies?

In Seeds of Destruction (1964), Merton frequently cited Pope John XXIII’s encyclical Pacem in Terris. Thinking especially about American politics, Merton wrote that the politician “should not be a ruthless and clever operator with unlimited power at his disposal, justified in taking any decision that serves him and his party or nation in the power-struggle. He must be—as Pope John says—a ‘man of great equilibrium and integrity,’ who is competent and courageous . . . And he must not evade his basic moral obligations for ‘reasons of state.’ On the contrary, statesmen and governments, which put their own interests before everything else, including justice . . . are no better than bandits” (165). Were Merton alive today, he would adamantly caution America that it is always dangerous to conflate another flawed human being with Christ, especially one who seeks power over others at any cost. Were he alive today, I am certain Merton would applaud Pope Francis’ efforts to make the world a more accepting, inclusive, tolerant, and loving place. Pope Francis has frequently acknowledged that, as a young priest, he was influenced by the writings of Thomas Merton.

Merton would be stunned to learn that Congress passed laws stating that corporations have the same rights as human beings. Merton would surely ask, “If corporations are human beings, do they also have souls?” He would be shocked at the deluge of money corporate lobbyists pour into the coffers of politicians so they will pass laws favorable to corporations, even to the detriment of actual human beings. Merton would also be alarmed by England’s Brexit (Merton lived in England and studied at Cambridge) and by America’s increasing sense of isolationism. Even in the mid-1960s, Merton cautioned against isolationism:

“We must condemn all isolationism and nationalistic individualism which might prompt a government to seek its own interests, ignoring and holding in contempt the rest of the world. At the present time all of the countries in the world are in fact so closely inter-related that no one nation can simply turn upon itself and seek its own advantage without affecting other nations.” (Seeds of Destruction, 166).

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Half a century after Merton’s death, politicians still use mass media to frighten voters at the ballet box; many of the most conservative religious in our nation too eagerly support a self-absorbed tyrant and all too willingly march to the drums of war instead of toward peace; racial tensions still explode into violence on streets across the nation; and the world’s ever-increasing population—more than doubled since 1968—continues to trash the planet. On the whole, I suspect Merton would be heartened to see that race relations in America are somewhat improved since the 1960s. No doubt he would also be heartened that one of the Catholic Church’s darkest secrets is being dragged into the light, revealed as it were. For Merton—a Catholic priest—would have understood that healing and reform cannot occur without revelation and repentance.

Someone once said that “the ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.” That someone was Thomas Merton’s friend, Martin Luther King Jr. Today, as then, the promise of America is being severely tested. We need people like these friends who stood up during one of the most challenging and controversial periods in American history with the sagacity to realize that protest is not a departure from democracy; it is absolutely essential to it. The framers of the Constitution understood this and made provisions to protect the right to protest peaceably. America, indeed the world, needs new Thomas Mertons, Daniel Berrigans, Rabbi Heschels, and Martin Luther Kings, courageous individuals—men and women, clerics or otherwise, prophets or not—who speak out against racism and xenophobia, inequality and intolerance, divisiveness, corporate greed, and violence. If Thomas Merton were alive today, like Wordsworth invoking Milton, he would say America is headed in the wrong direction.

__

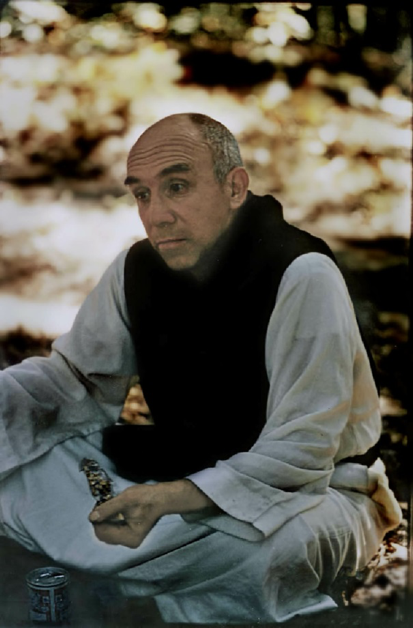

John Smelcer (PhD) is the author of over 50 books, including his award winning novel, The Gospel of Simon. His writing appears in over 500 magazines worldwide. He is the inaugural writer-in-residence for The Charter for Compassion, a global nonprofit founded in 2008 by Karen Armstrong (A History of God) to promote religious tolerance, nonviolence, social justice, and peace. In the spring of 2015, Dr. Smelcer “discovered” the worldly possessions of Thomas Merton, secreted away on orders of the monastery’s abbot after Merton’s death and safeguarded for half a century by a fellow monk and a nun (photo of the author at Merton’s grave). Dr. Smelcer is currently writing a book about the experience. Learn more at www.johnsmelcer.com.

John Smelcer (PhD) is the author of over 50 books, including his award winning novel, The Gospel of Simon. His writing appears in over 500 magazines worldwide. He is the inaugural writer-in-residence for The Charter for Compassion, a global nonprofit founded in 2008 by Karen Armstrong (A History of God) to promote religious tolerance, nonviolence, social justice, and peace. In the spring of 2015, Dr. Smelcer “discovered” the worldly possessions of Thomas Merton, secreted away on orders of the monastery’s abbot after Merton’s death and safeguarded for half a century by a fellow monk and a nun (photo of the author at Merton’s grave). Dr. Smelcer is currently writing a book about the experience. Learn more at www.johnsmelcer.com.