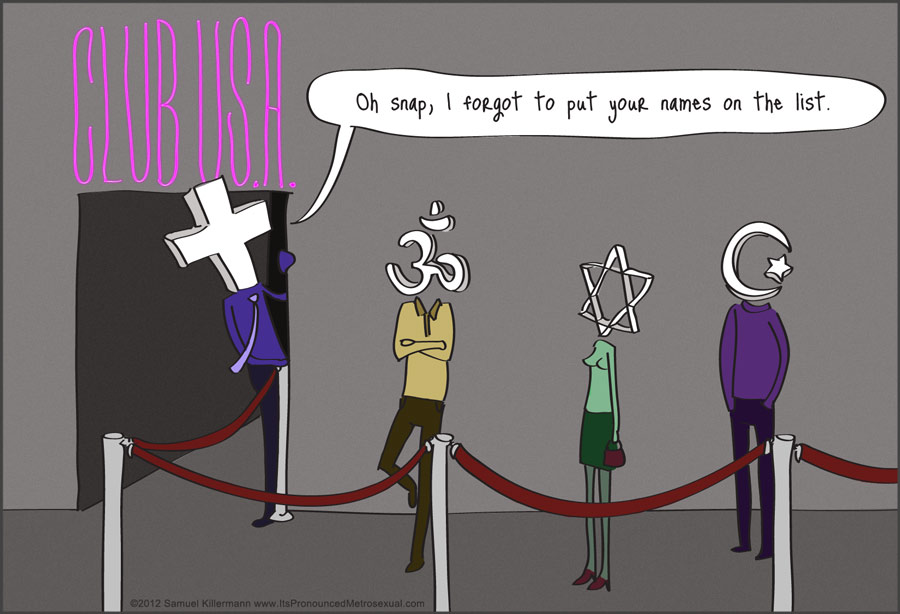

Image courtesy of Sam Killerman, https://www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2012/05/list-of-examples-of-christian-privileg/

Preface:

1. I am a deeply committed Christian. 2. Christian identity is understood differently throughout the Christian world in terms of practices and beliefs, and some of those differences manifest how we think and consider Judaism and the Jewish people. 3. What you will read here is the first part of a longer essay which will be published in separate installments by Tikkun in the coming months.

Christian privilege in the United States is an unrecognized phenomenon that reaches deeper, often more invisibly, than the day to day American Citizen would consider. As a person raised in the evangelical heart of the Middle America, I took for granted that the way I celebrated holidays, utter greetings, and make assumptions about the world was a normal, American experience. Growing up in Cleveland, my family lived intermingled with the Orthodox Jewish community of the suburbs of Cleveland. I attended activities and participated in local family swim time with my family members at our local JCC (Jewish Community Center) from the age of two on—my first experiences with a faith community that was not my own. I became aware that the Orthodox Jewish girls dressed a lot like my sisters and me, in long skirts and long hair, though the colors were often different and our holy day was different. I wondered what it would be like beginning one’s sabbath on Friday and not using electricity for a whole day, especially in cold Cleveland winters, when my parents did not have to work on our sabbath day on Sunday.

It has only occurred to me in adulthood that the way our country treats holy days, even considers the weekend, is very Christian-centered. Cleveland still practices not selling hard alcohol only on Sundays. Regardless of your personal feelings on consumption of alcohol, this practice derives from old Christian traditions. Even nationally recognized holidays when government offices are closed—New Year, Fourth of July, Thanksgiving and Christmas—are centered around Christian traditions. It is the Christian calendar new year based on the Gregorian calendars developed by a former pope that is observed in the United States as a day of national celebration. Living now in the Boston area, many businesses are closed on Good Friday, which is arguably one of the holiest days in the Christian tradition. None of these same privileges are enjoyed by those in the Jewish community: One of my Jewish coworkers was reflecting with me the other day as we approach Pesach (Passover), one of the High Holidays in the Jewish tradition, that to fully observe all holidays would require use of most of her allocated time off, leaving no space for vacation in her family’s life.

As my perspective continues to shift and expand beyond that of the conservative evangelical world in which I was raised, I find it crucial to maintain a foot in the religious conversation between Christianity and Judaism. I still consider myself to be a Christian, I still practice Christian faith traditions (now in the Catholic Church), but I have been deeply impacted through the course of my life journey as to the Christian teachings about Judaism. Typical Christian teaching with which I was raised, taught me that Christians were right about our beliefs, that the Jews were wrong, and that there is no way both groups can be right. As I have been deeply impacted by the Jewish Community at large and meaningful relationships with individuals who practiced the Jewish faith traditions—this conclusion, which I believe many if not most Christians believe to be a fundamental part of their Christian faith, bothers me.

The way many evangelicals and mainstream Protestants and Catholics conceptualize their faith as exclusive: there is one only one way to covenant with God, and that is through faith in His Son, Jesus Christ. As you likely know, Judaism, being a more ancient tradition from which Jesus Himself emerged, does not hold to the tenant that Jesus is a necessary component to covenanting with God. I use the term “covenant” because all of the Bible, both Hebrew Scriptures (referred to by Christians as “the Old Testament”) and the Christian New Testament, is about God’s relationship with humanity. In the earliest biblical phrases, God is depicted as reaching out to human kind and making an intentional act to develop a committed relationship with first one man, Abraham, and then all of his descendants (the Jewish people).

Christians draw upon this story of Abraham from Hebrew Scriptures, understanding themselves to have covenanted with God in a way that completed God’s covenant to humanity: through Jesus. In the traditional Christian narrative, the Jewish people broke the covenant with God—so God sent Jesus to offer the covenant to everyone else. In this way, Christianity teaches that the Jewish covenant with God was surpassed and superseded in favor of this new covenant that had different requirements: faith in Jesus. Implicitly, the Christian belief system teaches that Judaism was rejected, got it wrong, and now the only way to God is through faith in Jesus—meaning that the “old” Jewish covenant was broken with God (this rhetoric is known as anti-Jewish or adversos Judeaos language, a way of speaking developed out of Christian theology that demonizes Judaism and Jewish beliefs).

Developing my own faith practices in young adulthood, I engaged in academic studies of religion to understand how different religious communities developed identities and recorded these identities in their scriptures and interpretive traditions. Seeking to understand my own perception of Christianity as competing with Judaism for a covenant, I found significant dissonance between culture and the faith traditions I was raised in. Believing that faith needs to be responsive to culture, I parted ways with the Christian identity that espouses only one way to God (faith in Jesus Christ) and that the Jews got it wrong. I set out on a theological exploration encompassing over 7 years, two Master’s degrees to understand the origins of classical, anti-Jewish theology. I discovered that until the Second Vatican Council, Christians had typically perceived the Jewish relationship with God as a threat to the validity of the Christian belief that Jesus is God’s way of bridging the gap between humanity and God.

Up until the Second Vatican Council, a monumental shift in not only Catholic but Christian thinking in the 20th century, it was typical for Christians to espouse an adversus Judaeos (or anti-Jewish) belief system. This classical anti-Jewish mode through which beliefs about Jesus Christ (referred to by theologians as “Christology”) have been articulated by churches for centuries is not only violent, but has aided in spreading social anti-Semitism that culminated in the horror of the Shoah (the Holocaust). While faith practices may have become more socially tolerant in Christian identity, many Christians have yet to face the root of social intolerance for the Jewish people: the notion that Church replaced the Jewish people in a covenantal relationship with God. It is through this replacement theology that historically Christians have justified intolerance not just for Jewish beliefs, but Jewish people.

After the Shoah, the world reverberated with the affirmation to never again let so much hate fuel so sinister a mission to obliterate a people. Yet in that wake, Christians did not fully embrace the sacred duty to revisit the very fundamental elements of our theology that have been articulated in direct opposition to Judaism. As belief produces action, it is in the way Christ’s atonement in the Christian identity has been used to deny the validity of the Jewish covenant that Christians must recognize how adversus Judaeos articulations our theology fuel an insidious bias towards hate. Thus Christians must reconsider the very basis of how we understand the universal significance of Christ.

The impact of this adversus Judaeos Christology is very prominent in Christian understandings of Christianity’s election and covenantal status as God’s chosen people; the “New Israel.” The idea that the Christian Church became the “New Israel” through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross was read by the earliest Church Fathers as a logical conclusion to the Apostle Paul’s rhetoric concerning Judaism in the Epistle to the Romans. However, such Christology has led to a rivalry developing over the status of the covenant between Judaism and Christianity. Yet, is there any compelling reason to believe from Paul’s depiction of Christ’s work on the cross that Christianity replaced Judaism as God’s covenantal people, Israel? Rejecting this idea, is it possible to demonstrate the continued validity of God’s covenant with the Jews, while acknowledging the significance of Christ for how Paul understands of Israel through an unpacking of Paul’s articulation of Christ’s atonement in a contemporary theological context? As my argument unfolds, I will argue that it is, indeed.

Many Christian and Jewish scholars have written about the theological changes Christians must make in order to amend the anti-Judaism that overwhelmed Catholic theology prior to the Second Vatican Council. Though the statements the Council issued refuting anti-Judaism prevalent among Christians may have been revolutionary, the Roman Catholic bishops have not yet repented of some of the most fundamental doctrinal articulations which perpetuate adversus Judaeos theology in Christian communities. The present scope in this series of essays is to address only one of the many theological areas in need of reconsideration—Christology, the formation of the Christian identity around the life and work of Jesus Christ—and within Christology, a Pauline approach to understanding the Christ event as an atoning event which ushered in a new understanding of Israel.

Why the Apostle Paul? To summarize briefly, in all of the New Testament, Paul is the only writer to describe the death of Jesus with the same term for atonement as was used to describe the tradition of offering burn sacrifices in the Temple in Israel. As a very text-based religion, Christian scriptures depart most decisively from Judaism with the introduction of beliefs that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and that Christ’s death provided a blood sacrifice expulsing or atoning for the sins of the world. Paul’s depiction of the Christ even has historically been read through the lens of replacement theology within the Christian identity, fueling the Christian intolerance for Judaism. Rejecting replacement theology interpretations of Pauline atonement, I will offer a reconfiguration of Paul’s understanding of the Christ event as a way of validating the mutual right of Jews and Christians to participate in the covenant of Israel.

Replacement theology has been cited by many contemporary theologians as the root cause of Christian anti-Judaism. Replacement theologies are those theologies which view Christians as replacing Jews as the covenantal people of God. I characterize such theologies as anti-Jewish. Replacement theologies exist in contrast to theories of covenantal inclusion, in which the significance of Christ is dependent upon the enduring significance of the Jewish covenant. While this perspective differs from a typically Jewish understanding of the covenant of Israel, covenantal inclusion seeks to understand the Christ-event in relation to, rather than conflicting with, Judaism. Using the discipline of biblical theology to illumine the context of Paul’s interpretation Jesus within the Abrahamic covenant, I argue that the Jewish covenant can be validly included within Catholic covenantal theology while maintaining the universal significance of Christ. My work will highlight the distinctions between my interpretation of the Christ event from Paul’s writings from a replacement theology rendering more typical to Christian identity.

A Pauline model of covenant invites Christians to understand the Jews as maintaining a valid covenantal religion without denying the universal significance of the Christ event. According to this interpretation, because the validity of the Jewish covenant becomes a concern for the post-Shoah Christian, the Christ event does not effect salvation for the Jewish people but does take on significance for the Abrahamic inclusion of Gentiles within the people of Israel. My use of the term “salvation” differs from the typical Christian usage, referring to the desire for all peoples of the world to be united in the one God, who, though called by different names, Christians and Jews identify as the God of Israel. Paul envisions the covenant of Israel to be completed when all peoples of the world are united under the God of Israel, both Jews and Gentiles. My hope is that this analysis will demonstrate that there is a way for Christian and Jewish faith communities to understand themselves both to partake in the covenant of Israel that preserves the integrity of each religion’s approach to God—Christians through Christ and Jews through Mosaic Law observance.

Beginning in the Christology of St. Paul, Christian identity affirms Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection accomplished something for Jews and Gentiles that the covenant between God and the ancient Israelites did not: The Christ-event provided a means for the nations to covenant with God without taking on the particularities of Jewish Torah observance. Challenging replacement theological interpretations, this thesis will demonstrate that the question Paul’s gospel wrestled with, that of Gentile inclusion in the covenant of Israel, was accomplished through Christ in a way which did not undermine the particular covenant of Judaism. Framing Paul’s gospel in a Jewish understanding of covenant, that irrevocable relationship God established with humankind in Abraham, I will describe how Pauline understanding of Christ’s atonement allows for Gentile inclusion without conversion—an aspect of Paul’s view of covenant that challenges Jewish understandings of the covenant of Israel.

Recognizing the damaging theological and existential impacts of adversus Judaeos Christian rhetoric, it is important to root my claims in contemporary Christian tradition which supports the idea that faith must adapt in response to history. Turning to the inspirational document Nostra Aetate from the Second Vatican Council, there is a clear repudiation of anti-Jewish theology in Christian identity, though Nostra Aetate does not explain how Christians are to understand the significance of Christ for Christian identity if not universal to encompass the Jewish people. I argue that validation of the Jewish covenant affirms that independent of Christ, Jews can atone for their sins through sacrifice and prayer. Christian recognition that the covenant established with the Jews prior to the Christ event is eternal and irrevocable requires Christians to amend prior understandings of Christology. Such theological revisions are necessary in order to maintain that the Jewish covenant truly is eternal and was not replaced with a new covenant because of the Christ event. Thus, I argue in this article series that a post-Shoah Christian identity can claim that the Christ event had universal significance without requiring Jews theologically to acquire salvation through Christ.

On a more personal note: my own faith journey and formation of Christian identity has been something of a roller coaster. Discovering numerous historical accounts of violence and intolerance espoused in the name of Christ caused me years of spiritual wrestling, causing me to question the roots of my beliefs. As time has passed, I find myself as unable to leave Christianity behind because it is as much a part of me as my own blood relatives. I feel strongly that one cannot simply abandon a faith tradition that formed so much of one’s thinking and being in the world. Just as I would not disown my own family, but instead seek to encourage change and healing, so too I feel compelled to continue developing my Christian identity to be one responsive to the world around me.

My journey to understand the origins of anti-Jewish began through realization of difference and a desire for overcoming of misunderstandings and mischaracterizations of “Otherness” to use a term from the great Jewish philosopher, Emmanuel Levinas. The commonness of humanity has spoken to me, both during my times of theological study and in my call to a vocation as a mental health professional. Too many times have I understood the conflict between two parties to be fueled by identity politics rooted in fear. As Christianity emerged and took the world by storm, the passion of our theological founders, including the Apostle Paul, for unity as one body was lost in the concern of distinguishing ourselves from a faith group which we perceived to be competing with us for a special place in the eyes of God. Why can God have only one people? Why do those claiming to be God’s people need to so desperately label others as not part of the same covenant? I hope you will continue to walk this journey with me to an understanding of religious conviction being touched and changed through recognition of the beauty and the pain of an Other.

Kol Hakavod and thank you for this – I’ve talked about this for over 40 years, it seems to be a forbidden topic that is always pushed under the rug. Many Jews in the US are afraid to discuss the 2000 years of antisemitism and many Christians as well.

I grew up surrounded by survivors. My late parents immigrated to the USA, My father was a Shoah survivor (my grandparents were gassed in Auschwitz) , and my mother a Nazi refugee, many of her aunts, uncles and cousins were gassed as well. Antisemitism in Europe was wide spread for centuries, my maternal ancestors fled Catalonia in 1390 for southern Germany due to blood libel massacres. Yesterday, over 300 people were killed in Sri Lanka, in retaliation for last months Mosque murders by a white supremacist. The current administration fans the flames of racism, bigotry – When will the children of Avraham embrace and work together? I may not live long enough to see it, but I hope my children and grandchildren will. Keep up the good work. There is but one race- the human race.