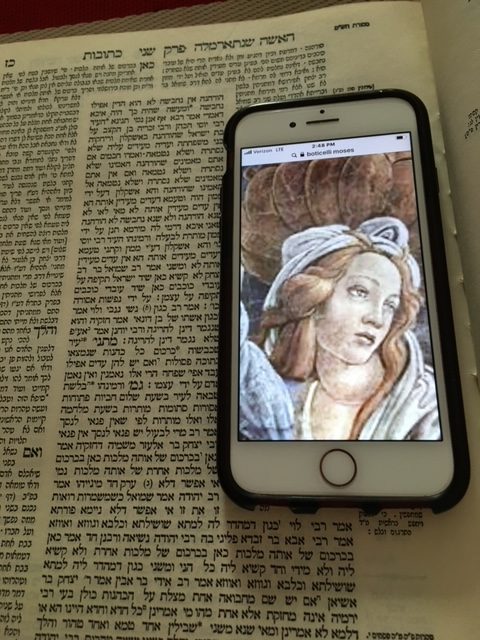

In one week of Talmud study I come across a great sage avowing that he’d rather see the Torah burned than studied by women, and an unflinching discussion of sex with a three-year-old girl. That was ten years ago and rebel-hearted feminist that I am, I’m still exploring the 37-volume, Jewish patriarchal beast known as the Babylonian Talmud. What keeps me coming back for more? What sort of wisdom can I hope to extract from a text so limited by its own biases?

I read the Talmud not with resentment or contempt, but with curiosity: Could it be that a 700-year-long conversation between scholars known the world-over for its intellectual refinement truly upholds these views on women? Or is there, as I suspect, something else going on here? I search for the nuances, the counter-voice, a strain you might identify as a sub-text which speaks in hints, allusions, contradiction, word plays and glaring silences. Behind and between the written words, I’m on the hunt for a deep fault line where, however disguised or denied, another layer of truth comes through. Naming this truth is like violating a last taboo: But this discovery teaches me much about myself and my relationships; naming it yields important insights into gender roles in ancient times and even more importantly, today.

………

I am far from the only otherwise-liberated woman to confess a strong attraction to these texts: The Talmud is not falling victim to cancel culture in feminist circles. On the contrary, its sharpest female readers apply the very intellectual acumen that the rabbis declared deficient in the “light-headed sex” to examining these texts through a newly-polished, gendered lens.

What does it mean to read Talmud through a gendered or feminist lens? Moreover, why do highly accomplished women bother to do so? Will we come up with anything that is ultimately transformative and faithful – both to the texts and ourselves?

Elana Stein Hain, scholar in residence at the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America puts it this way, “This is our great corpus of religious wisdom.I live in a talmudically-shaped religious world.” How to live her great reverence for the rabbis, while maintaining a concern for the treatment of women is a complex question. It requires some “separation between the Talmud’s contextual orientation and its timeless dimension.” How can this balance and this separation be achieved?

……………………

Women’s positions regarding Talmud study reveal where they stand – consciously or not — on the issue of male vulnerability. This year, the very admission of Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) women to the Talmud study hall made headlines in The New York Times. The women interviewed hastened to emphasize the non-provocative nature of their participation, insisting they were not there to subvert centuries of male authority but only to more fully appreciate its legacy. They display assiduous devotion to classical approaches to Talmud study, along with much caution never to challenge the “master myth” of male supremacy.

When studying Talmud with Modern Orthodox women, many of them self-ordained feminists, the tension between reverence and criticism is acute. I notice how their deference to tradition chafes against a sense of self: They long, yet hesitate, to pit female insight against a male-authored system whose strictures they still, to a great extent, live by. I listen as a woman PhD in Talmud from Yeshiva University teaches a passage from Ketubot about the penetration of a woman’s vagina, a tractate complete with rabbinic guidance as to how to assess the woman’s sexual activity from this exploration. I hear the teacher’s passing remark about being, “an object, always acted upon,” but never does she sound a purely mutinous strain, nor do any of her all-women students. I wonder about the degree to which a Modern Orthodox feminist will inevitably identify with the aggressor in this bias-laced terrain. When Stein Hain, an impressive Modern Orthodox scholar, asks how can we take these views on women, her implication is that whatever it takes, we must take them seriously.

.

Progressive women readers tend to be explicit, both about their umbrage at rabbinic sexism and their attraction to these problematic texts. (I wrote about this psychological paradox in an essay entitled Unrequited Love.) They don’t hesitate to read from a woman’s point of view, with an understanding of rabbinic thought that is informed by critical skills acquired in literary and gender studies. It’s rewarding to take a look at how some women academics read the text. Gail Labovitz, a distinguished scholar and professor of Rabbinic Literature at the Ziegler School, sounds the opening salvo, “Is there room for a generous critique? What opens up a story to her reading?”

……………………………..

Pioneering Israeli feminist and scholar Leah Shakdiel (herself a singular hybrid of Orthodox practitioner and militant feminist critic) urges us not to “turn our backs on this primitive book, or rewrite it to match our moral agenda.” Instead, Shakdiel advocates a commitment to studying all that came before and then, with a sense of history, to add “our anxieties and needs and passions and frustrations and pains and creations as another layer of understanding.” This leaves 21st-century women readers with plenty to do. When Stein Hain asks, “Is there a way to decode and reconstitute these views without imposing meaning that is really not there?” she is echoing Shakdiel and speaking for us all.

When embarking on Talmud study, Sarra Lev, a teacher at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical School, continues Shakdiel’s process when reminding us that we are entering a strange world, distant and antiquated. Its exotica and effrontery notwithstanding, the Talmud exerts the pull of familiarity. This creates a cognitive dissonance that disrupts our habitual certainty. In the best case scenario, we may even begin to question our way of seeing things, gaining awareness of our inner contradictions. Perhaps we will come to see and value that, “this is a type of learning that emerges from the nature of the very text in question,” in leading educator Marjorie Lehman’s words. The interplay between familiarity and mystery is after all the magical component of any stimulating relationship.

Now that we are thrown off balance, what’s next? Lev, who sees Talmud study as “a summons to our best self,” suggests posing what she calls “bridging questions.” These ask,“What is it that I am not understanding?” Do I need to hold on hard and fast to my own point of view? Do I need to rush to judgement – and shut the opposition down? Alternatively, “what might I learn about myself by not holding on to ‘I am right’? ”

………………………………

The Talmud is full of stories known as the aggadah, all of them told by men, many marked by ingrained sexism. In my own studies of the aggadah I’m looking for the subterranean counter-voice that, particularly when it comes to the role of women, whispers of an alternative understanding, one that can be excavated by reading against the grain. This approach can be illustrated through the timeless and troubling story of Rabbi Hiyya as told in tractate Kiddushin.

Rabbi Hiyya has sworn off sexual relations with his wife. One morning, his wife hears him praying for the fortitude not to be tempted. She is bewildered: Has he not told her that sex is something that no longer interests him? Why then, she wonders, must he pray to be spared its allure? Something clicks – she has an AHA moment and she takes action. She disguises herself as Heruta and in this get-up she vamps in front of her husband as he studies in the garden. Distracted, he asks her name and she replies, “Heruta’, adding, “I just returned today.” She ignites his not-so-dampened-libido, asking that he first fetch her a pomegranate. The unsaid in the text lets us know their intimacy is consummated. Change of scene: Back to the domestic hearth, where she is once again dressed in housewifely drear; he comes inside and faces her. Let’s leave it here, returning later for the story’s end.

How to begin reading against the grain? Labovitz, in her must-read essay, Heruta’s Ruse, gives us many pointers. First of all, we need to understand context. This story is set within a series of tales about men resisting sexual transgressions. Yet we know that sex within marriage is the front line defense against this sort of irregularity, so why then does the pious Rabbi Hiyya simply stop sleeping with his wife? If there is a reason for his deviance from the norm, why is it not stated? Something of importance has been left out. What is the text trying to tell us about him by its silence? Out in the garden, he is ready for the very activity he has been resisting: so here we find a tell-tale tension, an instance of control versus lack of control, a polarity that further alerts us to shades of meaning. On the other hand, we have details that are included that might be considered superfluous: How come he asks this strange woman her name? And when she answers, “Heruta,” letting us know that “she” returned that very day after time away, what does that mean? Alert to word play and double meaning, we know that Heruta means freedom; but some say it is also the name of a well-known harlot. The ambiguity prompts us to wonder if we are dealing with the return of an impersonated woman or a depersonalized energy. By including this exchange, what might the text want us to think about? Why should we be prompted in this way to think about Heruta at all? Next, why does the wife in disguise tell him to fetch a pomegranate? What other text does that evoke and what does its evocation reveal?

Viewing this story though a gendered lens brings us to the next question – what sort of role does this woman play? Have we seen her before in the canon of world literature? Labovitz, invoking the work of Rabbi Rachel Adler, answers in the affirmative. This wife can be identified as the Trickster, a female archetype who likes to throw things off balance. The tools of the Trickster trade are disguise, disruption, plays on double meanings of words (such as the name Heruta). Adler associates the Trickster with “the legal guerrilla,” she who unmasks contradiction by herself masking up; she who destabilizes and calls things into question. The Trickster poses a kind of riddle and in doing so, she up-ends many a conventional notion. As we will see, she subverts many a rabbinic party line and the Talmud lets her do it, too.

Now we return to the end of our story, and alas, it is not a happy-ever-after. The husband comes back inside, filled with self-loathing. He confesses that he has sinned and must therefore throw himself in the hot oven. Really, the wife asks, surely you must know that I am Heruta? He cannot take that in, so like the biblical Tamar who has to convince Judah of her identity after their sexual misadventure, the missus brings forth proof; in this case, she has the pomegranate. Having understood what transpired, the husband still cannot be moved. He insists that even if technically he did not sin, he certainly intended to. He lives out the rest of his life in a depressed stasis, nothing changes and he meets an early death.

The wife in this story speaks clearly to me as I listen for the intrusion of the counter-voice. Nameless, without status, she nonetheless reclaims her agency, the core privilege a female subordinate group is deprived of in a male dominant culture. This agency is sparked by her conscious awareness and played out in a clever ruse. She flings open the doors of domesticity to the invasion of the subversive, the radical, even the transgressive. Here I pick up a broad hint that she whom the culture represses is a source of initiative and wisdom that surpass male limitation. This marks her a Trickster, but to the rabbis’ credit, she is neither censured nor banished. She is clever, he is clueless and the rabbis tacitly support the very gender they officially disparage.

This is not the first or the last time I find myself skirting the fault line. In these chinks in the textual armor, strident misogyny is revealed in its true light, not as immutable wisdom, but as a near-desperate response to male vulnerability. The sages self-reveal as guardians of a system, to which, if we follow the clues, they pledge only surface allegiance. Male vulnerability remains an unspoken but underlining dynamic; to state it outright is to violate a cultural taboo. Still it is there, necessitating misogynist codes that a deeper wisdom subtly subverts.

In what way does a story like this add to our understanding of ourselves or our world? Is there anything here that is both faithful – in the sense of deeply revelatory – to our humanity and possibly transformative?

This story, like so many in the talmudic aggadah, doesn’t gloss over the messiness of life. Its gaps, contradictions and layered references slow us down, lest we banalize the complexity of the human psyche. The text won’t proffer a quick fix to a troubled marriage wherein a man can’t feel desire in a non-transgressive erotic arena. It is also frank about a woman’s valiant but failed efforts to fix it.

This story, like many others, throws us off balance with its admixture of the familiar and the strange, the daily and the fanciful, its skewered presumptions about the sanctioned versus the sinful. We must dig deeper into anything we don’t at first understand – in the characters and more critically, in ourselves. It warns us against taking sides and shutting down an opposing view. It asks us to expand and accommodate a lot of truths.

It unmasks male vulnerability without rushing to judgment, sparing us a trite prescription as to its remedy. In all these ways it shows us a path to a deeper understanding of ourselves and of the fault lines that run through our own lives and relationships.

Sarra Lev goes so far as to say Talmud study is “a summons to our best self.” A best self is not a perfect self, but rather one who is summoned to contemplate complexity – her own and others’. All who feel summoned to explore the Talmud learn that it takes all we have – vulnerability and courage, reverence and resistance — to rise to the text and to the task of being fully human.