In 2003 the Zur Baher committee petitioned the Supreme Court against the route of the separation fence, which was set unilaterally by Israel to serve its interests. The route was supposed to run near Jerusalem’s municipal boundary and thereby disconnect all of the homes of the Wadi al-Humos neighborhood from Zur Baher. Following the petition the State agreed to reroute the fence a few hundred meters eastward into West Bank territory. In 2004 and 2005 a “light” version of the separation fence was erected:. Instead of a concrete wall, as in most of the route of the fence in East Jerusalem, Israel built a two-lane patrol road with wide shoulders and another fence. The fence surrounds the neighborhood of Wadi al-Humos, which may not have been cut off from Zur Baher, but which was cut off from the rest of the West Bank by the fence, even though the land on which it was built was never annexed to Jerusalem’s municipal territory.

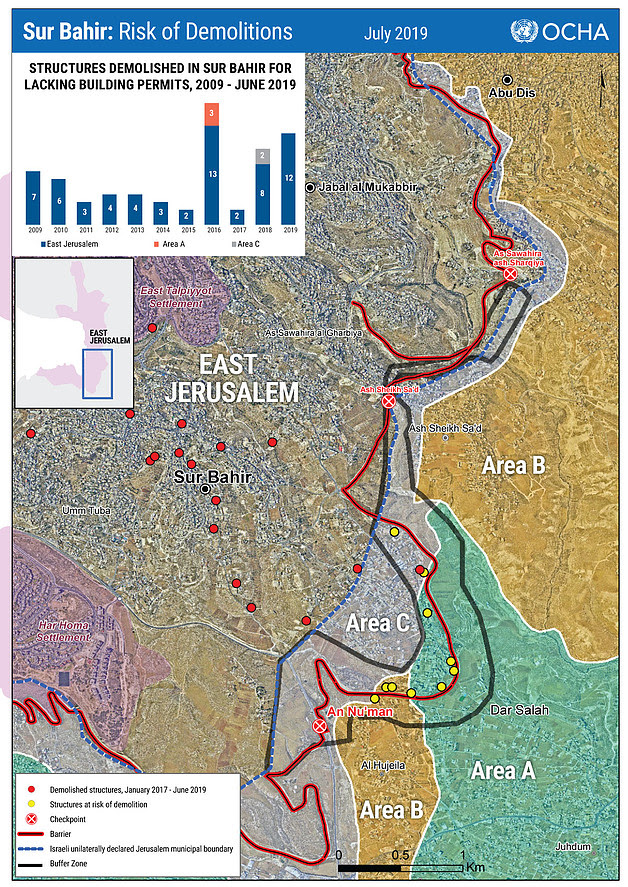

The Wadi al-Humos neighborhood is not considered part of Jerusalem, and therefore the Jerusalem Municipality does not provide the neighborhood with services, except for garbage collection. The Palestinian Authority does not have access to the neighborhood and therefore cannot provide it with any services, except for planning and providing construction permits. The neighborhood’s residents built its infrastructures themselves, including roads and water pipes from Zur Baher and Beit Sahur. On the southeastern edges of the enclave, which were defined by the Oslo Accords as areas A and B, the Palestinian Authority has planning and building jurisdiction. But most of it is defined as Area C, where the Civil Administration is responsible for the planning, and where, just like in the rest of the West Bank, it refrains from drawing up outline plans that would allow the residents to build legally. This Israeli policy, which completely limits Palestinian construction in East Jerusalem, causes a severe housing shortage for the city’s Palestinian residents, who are forced to build without permits.

In December 2011, about six years after the separation fence was erected in the area, the Israeli Military issued an order forbidding construction in a strip measuring 100-300 meters on either side of the fence. The Military argued such an order was necessary in order to create an “open barrier area” it needed for its operations, because the Wadi al-Humos area is a “weak point of illegal entry” from the West Bank into Jerusalem. According to the Military’s figures, at the time the order was issued, 134 buildings already stood on the land designated as a no-building zone. Since then dozens of additional buildings were built, and by mid-2019 there were already 231 buildings in the zone, including high-risers built only dozens of meters from the fence, and distributed between areas designated as A, B and C.

In November 2015 the Military announced it intended to demolish 15 buildings in Wadi al-Humos. About one year later, in December 2016, the Military demolished three other buildings in the neighborhood. In 2017 the owners and tenants of the 15 buildings under the threat of demolition petitioned the Supreme Court through the Society of St. Yves – Catholic Center for Human Rights. The petition argued, among other things, that most of the buildings had been built after receiving building permits from the Palestinian Authority, and that the owners and tenants were not even aware of the order prohibiting construction.

During the hearings on the petition, the Military agreed to cancel the demolition orders against two of the buildings. As for the 13 other buildings, the Military announced that for four of them the demolition would be partial. On June 11, 2019 the Supreme Court accepted the State’s position and ruled that there was no legal barrier to demolishing the buildings.

The Supreme Court ruling, written by Justice Meni Mazuz, fully accepted the State’s framing of the issue as one of purely security matter. It thereby completely ignored Israel’s policy of limiting Palestinian construction in East Jerusalem, and the planning chaos in the Wadi al-Humos enclave that allowed the massive construction in the area – of which the Israeli authorities were fully aware. Like in many past cases, the judges did not discuss in their ruling the Israeli policy almost completely preventing Palestinian construction in East Jerusalem, with the purpose of forcing a Jewish demographic majority in the city – a policy that forces the residents to build without permits. The severe building shortage in East Jerusalem, including in Zur Baher, was at the basis of the village’s demand to reroute the separation fence eastwards. Instead, the judges ruled that the home demolitions were necessary for security considerations, because construction near the fence “can provide hiding for terrorists or illegal aliens” and enable “arms smuggling.”

The judgment also clarifies the extent to which the “transfer of powers” to the Palestinian Authority in areas A and B as part of the interim agreements has no practical meaning – except for the need to promote Israeli propaganda. When it serves its own convenience, Israel relies on that “transfer of powers” to cultivate the illusion that most of the residents of the West Bank do not really live under occupation, and that actually, the occupation is almost over. Whereas when it is not convenient for Israel, like in this case, it sets aside the appearance of “self-government,” raises “security arguments,” and realizes its full control of the entire territory and all of its residents.

The judges rejected, almost flippantly, the argument by the petitioners that they did not know of the existence of the order forbidding them to build, and that they built after they relied on permits they received from the Palestinian Authority, and ruled that the residents “took the law into their own hands.” According to the court, the residents should have known about the order. The judges relied for this point on the provisions of the order requiring that its contents be brought “as much as possible” to the knowledge of the residents, among other ways by hanging it, along with low-resolution, difficult-to-understand maps, in the District Coordination Office, as well as on the State representatives’ arguments before them. In doing so, the judges completely ignored the relevant facts: that the Military took no action to bring the order to the knowledge of the residents before November 2015, that the order was issued years after the construction of the fence and the construction of the buildings, and even then – nothing was done for the first years to enforce it, and no real effort was made to ensure that the residents knew about the existence of the order – not even as obvious and simple an action such as pasting it to the residents’ walls.

This Supreme Court ruling may have far-reaching implications. In various places in East Jerusalem (such as Dahiat al-Barid, Kafr Aqab, and the Shuafat Refugee Camp) and other parts of the West Bank (such as a-Ram, Qalqiliyah, Tulkarm, and Qalandia al-Balad), numerous residential homes were built near the separation fence. Furthermore, as a result of the Israeli planning policy that prevents Palestinians from receiving building permits, many other buildings were built without permits, there being no other choice. The latest ruling gives Israel legal authorization to demolish all of the these houses, while hiding behind “security arguments” in order to carry out its illegal policy.