The author of this seminal book is none other than the son of Hitler’s governor of Poland and top-Nazi. Hans Frank was one of the main instigators of the Holocaust and personally responsible for Auschwitz—the camp and what went on there. Denouncing his father and all he stood for, Niklas Frank also wrote a most impressive BBC documentary My Nazi Legacy. In his latest book, The Dark Souls of German Nazis, Frank investigates what happened to ex-Nazis in the immediate post-World War Two years in Germany.

While his father was hanged after the Nuremberg trials for unimaginable war crimes, most of the other leaders of the National Socialist movement got off more or less scot-free. How could that be possible? Who allowed it to be possible? Based on substantial archival studies, Niklas Frank takes the Spruchkammerverfahren or Denazification Hearings, which were set up precisely to make sure that did not happen, to task. Between 1946 and 1950, thousands of German ex-Nazis were made to appear in front of such a hearing based on an Allied Control Council directive.

But then—all but a very few either served no time at all for their criminal acts or merely symbolic short sentences. Again one must ask: How could that be? That the Nazis were not eradicated and punished simply beggars the imagination, just as the Holocaust itself. Germany and the world let these impossible things happen.

In Germany, Denazification Hearings were inextricably linked to the word Persilschein. A Persilschein is a German idiom relating to a brand of laundry detergent (Persil). To gain a Persilschein, therefore, means to be sparkling clean, to be granted a carte blanche, to be forever cleansed of Schmutz. In the late 1940s, thousands of ex-Nazis were eager to get such a Persilschein, a certificate [Schein] that says “IV” or “V”, i.e., not guilty. The hearings’ five classifications were:

- major offenders (Hauptschuldige);

- offenders: Nazi activists, militants, or profiteers (Belastete);

- lesser offenders (Minderbelastete);

- followers (Mitläufer); and finally,

- exonerated persons (Entlastete).

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

Most of these not-so-ex-Nazis were acutely aware that they could not completely get off by trying to be classified as “exonerated person” (V). Instead, they opted to be classified as “follower” (IV). That was good enough and all most of them could achieve. Being classified “V” (unlikely) or “IV” (more likely) meant to receive the much coveted Persilschein. More or less it meant, “You are free to go” or “Get Out of Jail Free”.

Frank’s impressive archival work demonstrates exactly how, during the trials, ex-Nazis lied, deceived, concocted falsehoods, used deception, and withdrew into silence, while also falsifying records and making fake statements. They did anything, in fact, so as to be classified as “followers” (IV), even though many had clearly committed very serious war crimes, were part of Hitler’s killing machine, and supported Nazism as a state policy.

The key to Frank’s work is the tremendous amount of archival work he undertook. One needs to realize that it is humanly impossible for one man alone to go through all 3,660,648 files sitting in German archives. As a consequence, Frank selected files at random to produce a somewhat more representative picture of the Denazification Hearings that took place in all four zones occupied by the Allied Forces, i.e., the Soviet Union, France, Britain, and the USA.

Franks writes, ‘I was never disturbed by anyone while going through those files, except once when a woman asked me: “What do you do with the file of my father who was an Obersturmbannführer and fought so much against the Nazis?” Niklas Frank was gobsmacked!

An Obersturmbannführer was a high-ranking SS officer. Adolf Eichmann, for example, was an Obersturmbannführer. An Obersturmbannführer never fought against the Nazis. He was a main pillar in the entire Nazi structure. During Eichmann’s trial, chief prosecutor Gideon Hausner once asked Eichmann, “Were you an Obersturmbannführer or an office girl?” Perhaps the daughter of the SS Obersturmbannführer who had asked Niklas Frank that question also thought – or wanted to pretend – that her father too, was an office girl and not a high-ranking officer engaged in what Hitler, to the roaring adulations of his frenzied supporters, announced on the 30 January 1939, namely, “Die Vernichtung der jüdischen Rasse in Europa” – The annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe (Hitler 1939).

After the defeat of Nazi Germany by the Allies. many – by no means all – ex-Nazis were asked during the Denazification Hearings to justify their previous Nazi activities and to ‘prove themselves innocent’ (p. 9). In 1969, Justus Fürstenau ran a statistical search on the files and concluded: ‘Just 1,667 were Nazis class I, 23,060 class II; 15,425 class III; 1,005,874 class IV; and 1,213,873 class V’ (p. 10).

This means that 1.2 million were exonerated. Miraculously, the Denazification process had discovered a mere 1,700 Nazis. The rest of the accused war criminals were more or less innocent. One blanches at the sheer effrontery to reason and justice. Niklas Frank describes how the obvious contradiction between oiling the Nazi death machine and being innocent came into being. Overall, Frank found five noteworthy particularities:

- Men who were in a right-wing student fraternity strongly supported Nazism;

- Skilled workers who entered the Nazi party became what Goldhagen (1996) called Hitler’s willing executioners;

- Two-thirds of all Nazi informers were women;

- High-school teachers lied most outrageously about their Nazi past; and

- There is geographical north-to-south division inside Germany – the more south one travels, the more nasty and deceitful the lying became (p. 11).

In little more than 560 pages, Niklas Frank tells the story of the case files he investigated. He shows how Germany’s ex-Nazis were lying through their teeth to get a Persilschein. This allowed them to carry on as if no concentration camps ever existed and no Jew was ever murdered. Here is a typical case. Hans Mark joined the Nazi party in 1927, i.e., five years before Hitler gained power. He was an enthusiastic Nazi later joining Hitler’s SA in the rank of Truppenführer. The Denazification Hearing categorized Mark as ‘follower’ (p. 14).

A similar case is that of Karl Lades, the Nazi Ortsgruppenleiter who was still using the Nazi jargon of master race only three years after Hitler’s end, and he was judged to be a ‘lesser offender’ (p. 15). In his earlier days, Lades did not shy away from calling out, ‘Here’s where a Jewish pig lives! – die Judensau’ (p.19) when out hunting Jews (See Grabowski, The Hunt for the Jews, 2013). For these ignoble deeds, Lades sported the Nazi’s ‘medallion of honour’ (p. 23). He received it because of his work zur Volkspflege, i.e., in supervising the Aryan Volksgemeinschaft.

Richard Empter held many Nazi positions, member of the SS as Scharführer, then Oberscharführer, and finally SD-Sturmbannführer. At the time, many Nazis wanted to be a little bit of a Führer. Hence, one finds a plethora of Nazi ranks and titles that include –führer. Top SS-Nazi Empter, however, was declared only a humble ‘follower’ of the Great Leader (p. 42).

The same medal was granted to Ernst Heinkel, owner of the Heinkel factory where KZ-slaves were made to work under horrific circumstances. Heinkel said, “I felt for the bad living conditions but couldn’t do anything”. The man who benefitted substantially from slave labor was also categorized as a mere ‘follower’ (p. 43).

One of the more interesting case files must be that of Fräulein von Osten, wife of Reinhard Heydrich. Heydrich was responsible for the death of thousands. Later, he was assassinated by Czech resistance fighters (p. 45). At their wedding, the infamous the Horst Wessel Song, the Nazi anthem, was performed. Hitler gave the newlyweds Panenske Brezany castle, which became Heydrich’s weekend residence.

After the war, Mrs. Heydrich told the Denazification panel: ‘I never felt empathy for the Jews and that was in line with the German Volk’ (p. 47). Furnished with Nazi party membership No 1,202,3800, Lina Heydrich employed slave labour from a nearby concentration camp. Niklas Frank also lists the total income of the Heydrich family. From such details, it can be seen that Hitler’s upper apparatchiks lived a life of comfort and ease, while ordinary German soldiers were expected to die a hero’s death on the Russian front for a pittance.

After her well-heeled life near Prague, Lina was sentenced to live in prison in the CSSR by a Czech court. She had been found guilty of having mistreated Jewish labor, feeding them table scraps, and asking her household staff to beat Jews with whips and clubs. ‘Lina personally kicked laboring Jews. Once, when a Jewish prisoner was hit by a falling tree, Lina Heydrich waited four days to get him to a hospital. The man died’ (p. 49).

Mrs Heydrich liked to ‘watch working men and women through her binoculars from her balcony. She also decreed the most brutal punishments’ (p. 50). When begged, “Dear Frau Heydrich, please let those Jews live a little longer” (p. 50), she showed not a shred of mercy. After the death of her husband, she took on the running of the estate with these words: ‘Send me fifty more Jewish prisoners’ (p. 55).

Once transferred out of the CSSR, a West-German Denazification Hearing found Lina Heydrich to be a “follower” and ‘ordered her to pay 75DM payable in three installments of 25.-’ (p. 56). Archive files record that a prisoner testified: ‘Mrs Heydrich had four children. Whenever they saw us Jewish prisoners, they spit on us’ (p. 59). The man continued, ‘Every morning, there was a roll-call [Appel] where we were told, “If you work hard, you may have a chance; if not, you will surely go to Auschwitz!” (p. 60).

Another witness added, ‘We were forced to sleep in a stable confined to a small space, hygiene was bad (fleas, tics and other parasites). We had to work very hard for 14 to 18 hours per day… We received insufficient food’ (p. 63). The witness said, ‘We were ordered to address Ms Heydrich as ‘Gnädige Frau’ [gracious lady], while we were to speak to ‘the women in the camp as ‘Judensau’ [Jewish Sow]’ (p. 60, 64). Jews were constantly exposed to the capricious whims and mood swings of Frau Heydrich.

Years later, she wanted to sell some stamps honoring her husband issued by Nazi Germany in a local philatelic shop in Munich. As she placed them on the counter, the shopkeeper said, “I don’t want that criminal”, to which her ladyship replied, “He was my husband” and huffed out (p. 65) to live out the rest of her life as a certified Nazi “follower”. She too had a Persilschein.

Annelies von Rippentrop showed a similar attitude. Her Nazi Party membership is dated 1933. Frau Rippentrop said ‘I did not know anything about the crimes of the Nazi system’ (p. 99). Therefore Mrs Rippentrop, a top-Nazi woman, was found to have been a mere ‘follower’ (p. 107). The same verdict was given to Michael Mayer, a Nazi party member since 1932, and a ‘zealous Nazi’ (p. 111) who claimed, ‘Without my knowledge, they shot two-hundred Jews in the forest’ (p. 111).

Meanwhile, one of the actors in the Nazi propaganda film “Jud Süß” (Schulte-Sasse 1988) where he ‘played four different characters, was found not guilty – entlastet’ (p. 112). How perspicacious and wise were these verdicts!

Under the sub-heading “The Beneficiary of the Devil”, Niklas Frank examined the files of his own mother, Brigitte Frank. According to the son’s recollection and the files, Brigitte enjoyed a comfortable life among Germany’s higher Nazi echelons. She had a Mercedes and chauffeur at her disposal, while also having use of the state limousine of her husband. She lived in a spacious mansion as residence in Berlin, also using Castle Kressendorf near Krakow in Poland.

Some of her ‘belongings, including fur coats from the Warsaw ghetto [which were stored in] Baroque-chests stolen from France’ (p. 133). Her own son Niklas Frank concluded: ‘People in the ghetto were forced to sell their belongings at any price my mother dictated’ (p. 144).

After Nazi Germany was defeated, Ms Frank claims ‘I did not benefit’ from the Nazi system (p. 134). Strangely, by the end of the war, Mrs Frank had ‘three-hundred pair of shoes… [meanwhile] her servants were mistreated [by her] receiving only repulsive und unhealthy food scraps’ (p. 137). Even her own chef testified, ‘I was always hungry, especially when Mrs Frank was there…I never got a day off’ (p. 138).

The cook also said, ‘We had to address her with Frau Reichsminister’ (p. 139), even though Ms Frank was not a minister at all. The witness also stated, ‘They [the Franks] enjoyed a shameless life of luxury’ (p. 141). There was also priceless jewelry’ (p. 143) and a ‘golden cigarette case valued at 8,000 Reichmarks’ (p. 144; approx. €56,000 in today’s money). Meanwhile, ‘Hans Frank was seen as…the king of Poland’ (p. 141).

His son, Niklas Frank, uncovered a letter written by his mother to her friend in which Mrs Frank wrote, ‘When I think about the past, we were ruthless’ (p. 141). After all this, the case against Brigitte Frank was ‘shelved’ (p. 145) on 3rd March 1946. The judges could not make up their mind, the case being, to them, too inconclusive and ambiguous.

And there is more like this. The case of Emmy Göring, wife of Hitler’s deputy, was strikingly similar. In her trial, a witness testified that ‘Frau Göring lived a life of luxury…she was the biggest squanderer of all…she lived off the back of the German people’ (p. 263). Mrs Göring got the Nazi party membership number of a dead member’ (p. 266) falsely depicting her as ‘an old fighter’ (p. 275) of the Nazi movement. The number of party membership was crucial to the Nazis. The lower the number, the higher the reputation, with anything registered pre-1933 being particularly well regarded inside the Nazi party.

Ms Göring also received special funding called ‘Ehrensold’ (p. 266) – sold is a special German term indicating payments to soldiers or civil servants. Ms Göring was neither a soldier nor a civil servant. At the hearing, Ms Göring said, ‘my husband was not a prototype of a Nazi’ (p. 275). She also belittled the Holocaust calling it ‘grotesque’ (p. 279).

Later in life, Ms Göring published her memoirs in which she wrote ‘why did my husband had to suffer such a death? He was always there for others, he gave everything to others, [he was full of] love, kindness, happiness, understanding, help, and gave assistance [to others]…he was faithful’ (p. 283).

Years after Ms Göring’s Denazification hearing, Niklas Frank tried to make contact to one of the Göring children. When he called, Edda Göring picked up the phone asking, “Are you the son of Hans Frank…the one who wrote the book about your father?” Niklas Frank said, “Yes” and Edda Göring hung up’ (p. 284).

Perhaps the former US Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright was correct when she noted, ‘It is easier to remove tyrants and destroy concentration camps than to kill the ideas that gave them birth’ (Albright 2018:191). Not to mention those who store these ideas in their minds and bide their time until they can put them in practice again.

Finally, there is the story of the dentist Heinrich Claussen, a Nazi party member since 1931, a local Nazi thug, and Obersturmbannführer (p. 433). Claussen liked to line up Aryan children in two queues on two sides to build a long alley-way. Jewish children had to run the gauntlet through that corridor [Gasse] while being mocked, spat on, and beaten by the Aryan children on each side. Here’s the testimony of a local boy made during the Claussen hearing,

Have you ever thought about the Jewish children?

p. 438

The night before their expulsion from Föhr, locals threw stones at the windows of the children’s home and shouted dirty slogans. The children had been weeping in the dormitories … they were being led away from the windows into a safe interior dressed in their nightgowns. The next day they had to walk two kilometers to the port. Maybe they’re already being mobbed on the way. Then they arrive … hold on to each other’s their hands anxiously, begin to cry [in] horror with their lips pressed together. Then it’s off: they are sorted from right to left, slapped, then gobs of spit come along, and from hate-soaked mouths came shouting … they understood only single words like “Jewish pigs” and “parasites” …

Have you ever imagined yourself being a Jewish child in this?

“No, no … when I think of it, I feel like I’m being swept away.”

It was Claussen who instigated all this torment… maybe like pulling out teeth without an anesthetic. At Claussen’s Denazification hearing, he was found to be a lesser offender – Minderbelastete (p. 438). Again we are stunned into silence by the audacity of these supposedly objective judgments. Niklas Frank’s book is full of stories like these. In minute detail, Frank follows the testimonies and records made during the Denazification Hearings and he concludes that all of them were lies and deceptions which came thick and fast from virtually all the ex-Nazis.

When reading through such testimonies slowly an awareness grows that Germany’s Denazification during the immediate post-Nazi years was organized, not to detect and de-nazify Nazis, but rather to hand out Persilscheine. Murderers, torturers and sadists became lesser offenders or mere followers on a massive scale. Niklas Frank’s book still awaits translation into English.

Given what this brave and moral man has unearthed, perhaps there are two permissible conclusions: for one, ex-Nazis showed their dark soul and their cowardly natures when they lied to absolve themselves from their heinous crimes; and second, there was in fact no Denazification program but merely a systematic whitewashing so that the whole horde of ex-Nazis could re-enter German society and live an unearned peaceful life in post-war Germany, unlike their millions of dead and traumatized victims.

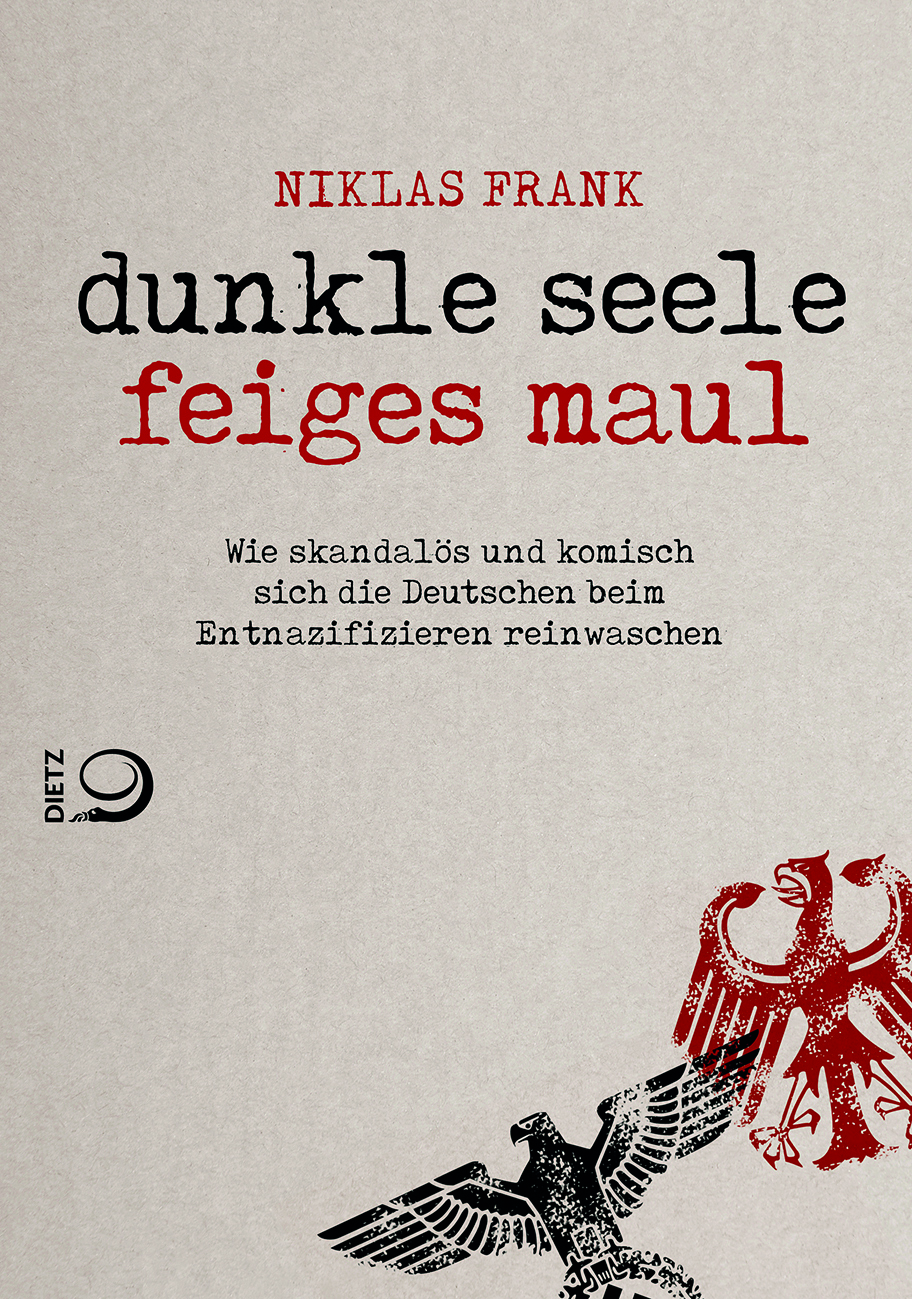

Niklas Frank’s German language book Dunkle Seele, feiges Maul is published by J. H. W. Dietz Press in Bonn, Germany.

References:

Albright, M. 2018. Fascism: A Warning (with Bill Woodward), New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

BBC 2015. My Nazi Legacy (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=07X5MMgTJU4, accessed: 15th February 2020).

Grabowski, J. 2013. Hunt for the Jews: Betrayal and Murder in German-Occupied Poland, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hitler, A. 1939. Reichstag-Speech (https://footage.framepool.com/en/shot/150074222-reichstag-session-adolf-hitler swastika-dictator, accessed: 15th February 2020).Schulte-Sasse, L. 1988. “The Jew as Other under National Socialism: Veit Harlan’s Jud Süß,” German Quarterly, 61(1): 22-49.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

Hitler and his fascists where Not confronted early on,same, same today. Trump ( although ) no Hitler ( He had a brain ( Evil ) was let take control of a Major Political party , because short signedness and greed.

We Liberals, Progressives , Moderates of every color MUST stand United against this threat to our Democracy.