He was Chicago’s Fighting Hebrew, from the Kraków family of fishmongers

on Maxwell Street, who clubbed and dazed the great Dempsey, who rammed

his head in the chest of the giant Carnera, who swung so hard he spun around,

who wore his shoes on the wrong feet in the ring, who heard the Yiddish curses

of his sister the manager leaping in the first row, who smiled for the newsreel

cameras with fewer and fewer teeth, who married a stripper, who coiled his

right hand in a fighter’s pose on the cover of The Ring magazine, who filled

stadiums with the clamor of refugees and worshippers from synagogues.

Please don’t let him hit me again, pleaded the King to the referee, squatting on

the bottom rope in the stadium where the White Sox threw the World Series,

the lights above the ring spinning two minutes into the first round, after

the hands of Joe Louis burned the grid in the brain of the King, who stumbled

face first to the canvas, the fighter dissolving into a fishmonger. The reporters

called him a coward, a deserter fleeing from the trenches to the firing squad.

Thirty years later, Union County College declared April 4th King Levinsky Day,

and a Loser’s Fund of twenty dollars for a student with holes in his pockets.

When he quit the ring, the King sold ties, navy blue with a sprinkle of white

flowers, the name King Levinsky and a boxing ring emblazoned on the label.

He worked the tables at lunchtime in Chicago. Do you remember when I fought

Joe Louis? the patter began. Neither do I. The King would brandish shears

to snip off a customer’s tie, then pick out a new one from his suitcase.

Matches real good, he would say. He worked the crowds at the fights,

and the mobsters who always bet on the winner paid fifty bucks a tie.

When his sister died, he cried in a phone booth: I ain’t the King no more.

I worked in the stockroom at Sears with a middleweight who could have been

the bastard son of King Levinsky. Herbie Wilens, called The Hebrew Hitter,

would hit me, sparring bare-knuckled to mesmerize the boys in the stockroom,

the janitor glancing up from his mail order bride magazine. I was a boy who

drank cough syrup from the bottle, too slow to duck the right hand that

lit a match in my ear again and again, the heat spreading across my face.

Don’t kill him, said the janitor. Herbie stopped hitting me and hit boxes instead,

the boom of his hands crushing the cardboard where a bicycle or lawnmower

waited for Christmas. I was a poet, so I would write a three-word poem

under every dent left by the hands of The Hebrew Hitter: Herbie Was Here.

Herbie would roar at the odes I inscribed to praise him on dented

cardboard boxes. We split twelve packs of Budweiser in his basement,

though I grimaced at the foam surging in my belly. We inhaled bong hits

on his couch, though the bubbling smoke of the bong seared my throat.

I imagined my uvula, that little punching bag, bright red, the skin peeled

away, as I wailed with Jimi Hendrix singing All Along the Watchtower.

I told Herbie about the girl I kissed, how she hid me in her bedroom closet

till her Old Testament father shuffled to sleep, how I wrote her a poem

where she swam in a waterfall, how she dropped me and kept the poem.

Herbie told me about his father the brawler, swinging and skinning his knees

on the sidewalk. He told me about sparring the Mexican middleweight who

scorched his ribs, ranked number ten in the world. Leo hits so hard, he’d say.

The Hebrew Hitter trained on Budweiser and bong hits with me all night.

Later, The Ring would call him inept Herbie Wilens of Gaithersburg, Maryland.

A Puerto Rican fighter from Jersey City, who would become the champion

of the world, later a security guard grateful to Jesus, strafed Herbie with hooks

and uppercuts till he stayed on his stool, chest heaving. At the Budweiser

Washington Championship Boxing Games, signed by the matchmaker to lose,

walking to the ring in his robe with the Star of David, he remembered the right

that would spank my face till I glowed red as the light blinking on a ring post,

and Sugar Ray Leonard’s older brother, Roger the Dodger, sprawled across

the mat. The crowd cheered the loser when he lost the split decision.

The days of sparring in the stockroom gone, the other stockboys buried

in the dumpster of my imagination, I dug for Herbie and found the body:

dead at fifty-five, cancer, the obituary listing the funeral home to visit years

after visiting hours were over, and his nickname nowhere on the record.

The Hebrew Hitter could have been the bastard son of King Levinsky,

even if he never sold me a tie in navy blue sprinkled with white flowers.

There was beer and weed on the couch, Hendrix in my blasted ear, the poem

of waterfalls where I drowned at sixteen. I carved the words Herbie Was Here

on every cardboard box dented by his hands, and he would roar like a fighter

on the cover of The Ring magazine, middleweight champion of the stockroom.

Share on Social Media:

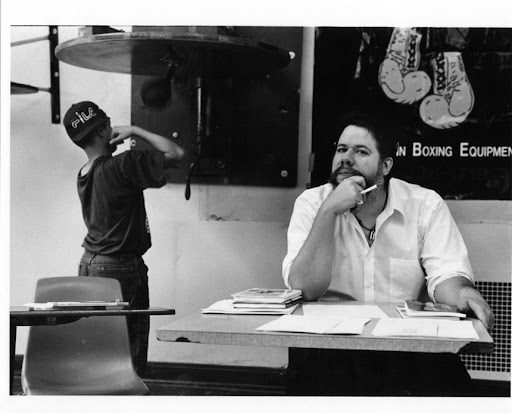

Martín Espada’s latest book of poems is called Floaters (2021), winner of the National Book Award and a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. He has received the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the Shelley Memorial Award, a Letras Boricuas Fellowship and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Photo credit: Lauren Marie Schmidt, 2021.