Walter Benjamin’s Vision of Hope and Despair

“A Klee drawing named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

— Walter Benjamin,

“Ninth Thesis on the Philosophy of History”

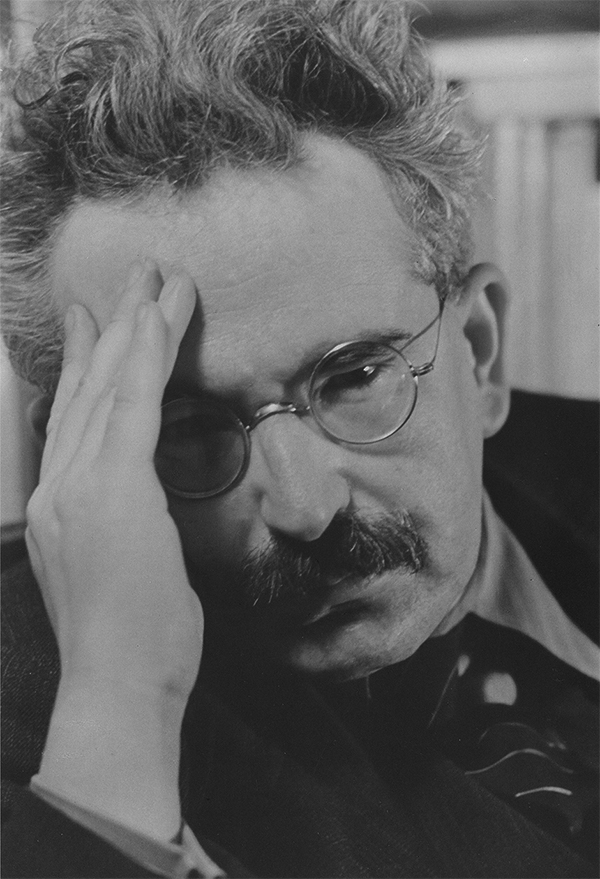

Walter Benjamin, a German Jewish literary critic and philosopher, had purchased Klee’s watercolor of an angel in Munich for the equivalent of about thirty dollars. Writing about the image in 1940, his interpretation is not an optimistic one: so-called “historical progress” is a foolish illusion. At the age of forty-eight, he had lived through World War I and its aftermath. Now, in the second year of yet another war, the course of history had been commandeered by fascism, a “catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin.”

The bleak sense of inevitability that Benjamin projects in this discussion of Klee’s drawing is contradicted, however, elsewhere in his commentary on the “Philosophy of History,” where he speaks of “fanning the spark of hope” and a “leap in the open air of history.” As well, there is a tension that animates the image itself: the eyes of the angel (whose appearance is as much female as male) point to one side, while the rest of the body twists a bit in the opposite direction, suggesting arrested movement, possibly a conflict between past and future. Hope is not extinguished: there remains at least the potential for movement toward a better world.

Benjamin’s own life, though, did not go in that direction. Several months after he penned his “Ninth Thesis,” he himself was destined to become one more lifeless body tossed upon the heap. Seized by authorities in Spain during his effort to escape across the Pyrenees from Nazi-controlled France, he committed suicide. But Benjamin probably did not take his own life only because he feared being turned over to the Nazis. Years earlier he had described himself as brooding and melancholic, and had considered killing himself.

“Melancholy” is no longer the most common way of describing those who experience life as no longer worth living. The routine term today is “depression,” a condition of presumed chemical imbalance for which a standard remedy has become a tablet designed to elevate neurotransmitter activity inside the brain. According to the World Health Organization, about 5% of adults worldwide suffer from depression, which is commonly treated with medication. Here in the United States, nearly 25 million adults have been taking antidepressants for at least two years.

To some extent depression is biologically rooted, possibly handed down from one generation to the next via genetic inheritance. But DNA is not the only way in which our lives are interwoven, for despondency and despair correlate with what goes on in the social world. When the rate of unemployment rises even a fraction of a point, the suicide rate typically turns upward as well. Historical circumstances can shape our lives as powerfully as the biologically given bodies through which we live.

Pandemic disease, climate change, economic hardship, racism, and war are current conditions that contribute to a loss of hope. Discouragement today resembles, it seems to me, the sense of a foreclosed future that afflicted Benjamin’s generation in Weimar Germany. Ours too is a time of accession to power of authoritarian regimes that threaten to eclipse and extinguish democracy altogether, shutting down the very possibility of opposition. Yet, at the same time that I am writing this article (at the end of 2022), there are strong cross-currents. Ukraine’s fight for freedom is a striking example. Elsewhere too, including in the United States, people are fighting for free and fair elections, workers’ rights and dignity – for all the causes that cry out for attention.

The Weimar Republic. To be sure, melancholy can impel the human spirit in various directions. It may strangle one’s interest in the world and one’s willingness even to get out of bed in the morning. But it can also incite rebellion against an intolerable social order and outreach to find an alternative. Yes, Walter Benjamin and many of his contemporaries experienced the First World War as immensely destructive and horrible. Yet the revolutionary upheaval that occurred in its wake, in Germany, Russia, and elsewhere in Eastern Europe, seemed to be a powerful and promising turn toward freedom. Europe’s social democratic movements at this time represented one of the best chances humankind had during the 20th century of forestalling the conquest of the world by the forces of wealth and militarism.

If the Weimar Republic that came to power in Germany at the end of the First World War had been able to survive the aggression unleashed against it, by the right and by the extreme left also, it might have inaugurated a liberating historical journey. For in spite of its dire circumstances, including the punitive Versailles Treaty, the Weimar Republic’s initiatives were phenomenal: legally required collective bargaining agreements and unemployment compensation, free public education, a constitution establishing parliamentary democracy and affirming basic human rights. The Republic built railways, bridges, and roads, along with houses for over three million Germans. The Works Councils Act enacted in 1920 gave workers a voice in determining the conditions of their own labor.

But the government lacked the resources to keep and amplify these reforms. All of the Republic’s policies were undermined by political opposition and, above all, by extreme economic poverty that increased homelessness, despair, and crime.

In Germany following the War, there occurred a kind of social disintegration. Artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix satirized an urban existence consisting of a jumble of separate paths pursued by isolated individuals.

This was the situation of the “Lost Generation” in Germany in the 1920s, disillusioned not only with the traditional creeds of nationalism and religion, but also with collective affiliation of any kind. Several of Benjamin’s close friends had taken their own lives, including his Aunt Friederike Josephy, who had been like a second mother to Benjamin, intervening in his disputes with his father and introducing him to the mysteries of art, literature, and science. Benjamin was deeply shaken by these deaths.

Among those affected by the travails of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s were my mother and her brother Ralph Zucker, a Jewish student of medicine in Leipzig. They were born in the first decade of this century into an upper middle-class, assimilated Jewish family in Dresden. My grandfather was a successful chemist who had fought in the army for the Kaiser during World War I and returned home decorated with medals. Although the family was affluent, and the children well provided for materially, my uncle Ralph became despondent and killed himself in 1927. German writer Erich Kästner wrote a novel, Fabian (1931), that recounts this suicide.

In 1940, a month before Benjamin lost his life in the Old World, I was born into the New one. My father and mother were of the same generation as Benjamin but had emigrated to the United States in 1938. Like so many European Jews who narrowly escaped the Holocaust, they deliberately wanted to put all that behind them. What had happened in Europe was never mentioned in our household. For my father especially, the past was a closed book. When I was born, my mother wanted to name me “Ralph,” in memory of her lost brother. My father objected, and “Ray” was chosen as a compromise. As a child, I can remember my mother Hilde in the kitchen, shedding tears as she prepared dinner. I could make no sense of this at the time. Now, more than half a century later, I wonder whether – midst the other disappointments and satisfactions in her life – she was recalling her brother and others left behind in Europe.

The Homeland’s Happiness and Sadness. Benjamin experienced the condition from which the Angel of History cannot escape as a personal as well as a political impasse. Although he did not go to prison or suffer any other severe repression, his outlook on life is inseparable from the defeat of progressive forces in Germany in the 1920s, leading up to the seizure of power by the Fascists. For Benjamin, it is as if the boundaries between private and public, between individual experience and the social world, exist only in order to be trespassed.

In autobiographical remarks dedicated to his son Stefan, Benjamin reminisces about a childhood in which the boundaries of the self easily form and dissolve, as the child joyfully merges with surrounding objects: a moist cloud in a watercolor painting, a soap bubble, a curtain, or even dining room furniture:

Standing behind the curtain, the child [who is hiding] becomes himself something floating and white, a ghost. The dining table under which he is crouching turns him into a wooden idol in a temple whose four pillars are the carved legs…. Anyone who discovers him can petrify him…under the table, weave him forever as a ghost into the curtain…. And so, at the seeker’s touch, with a loud cry he drives out the demon who has so transformed him – indeed without waiting for the moment of discovery, he grabs the hunter with a shout of self-deliverance.

A child’s imaginative engagement with the world – playing with life and death, escaping from the hold of the curtain but then returning to abandon oneself behind it again – resembles Benjamin’s approach to a literary text, an architectural monument, or a metropolis like Berlin or Paris. Benjamin’s love of literature, ranging from academic treatises to mystery novels, is prefigured in his description of what happens when a child picks up a storybook:

The hero’s adventures can still be read in the swirling letters like figures and messages in drifting snowflakes. [The child’s] breath is part of the air of the events narrated, and all the participants breathe it. He mingles with the characters far more closely than grown-ups. He is unspeakably touched by the deeds, by the words that are exchanged, and when he gets up, he is covered over and over by the snow of his reading.

The child’s mimetic imagination that Benjamin celebrates here proved to be no portal to happiness in his adult life; on the contrary it made him more responsive to “the homeland’s sadness,” as he called it – the world in ruins around him that he witnessed. Like Klee’s Angel, Benjamin felt caught in history’s tangle – propelled forward, yet incapable of disengaging from the past.

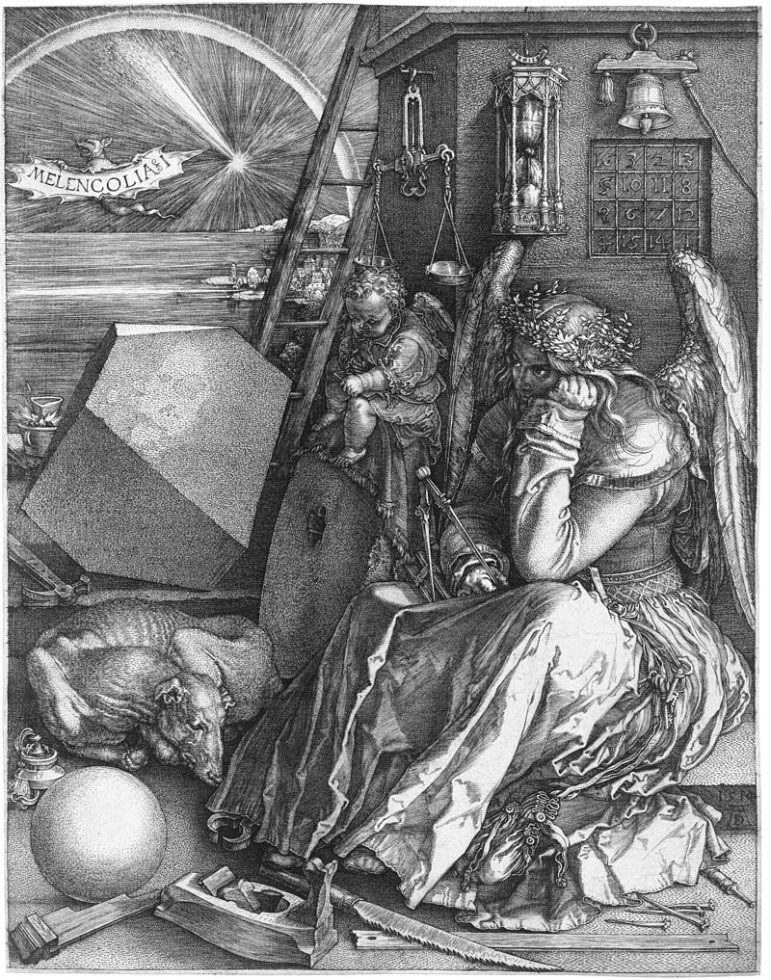

Despondency enters also into another work of art that Benjamin interpreted: an engraving by the 16th-century artist Albrecht Dürer entitled “Melancholia I.” Benjamin perceives “The deadening of the emotions… an intense degree of sadness.” The compass and other instruments of mathematics and science are of no use to the disconsolate angel who stares at surroundings deprived of meaning. Yet, through the window of her study, the heavens illuminate a transcendent seascape.

Wikimedia Commons

Seen in this light, melancholy possibly leads not to resignation, but to an impassioned rejection of the status quo that harbors a utopian impulse. There is in Benjamin an anticipation of renewal and liberation that fractures the conservative forms that define everyday life, including our ways of remembering and misremembering the past. The destiny of prior generations, Benjamin believes, is always open-ended and in need of completion. He submits that

The past carries with it a temporal index by which it is referred to redemption. There is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one. Our coming was expected on earth. Like every generation that preceded us, we have been endowed with a weak Messianic power, a power to which the past has a claim. That claim cannot be settled cheaply…. even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he triumphs.

A mission of the historian, writes Benjamin is to safeguard the “spark of hope in the past,” as if memory could ignite a prairie fire across the generations. Such memory is identified by Benjamin as “the quintessence of Judaism’s theological concept of history.” Embedded within Jewish tradition is extraordinary hope – Biblical accounts of the Maccabees, for instance, remind us that liberation movements can succeed against seemingly invincible adversaries.

Notwithstanding Benjamin’s advocacy of such activism, he himself did not join any social movement or political party. His messianic and apocalyptic sense of what would be needed to redeem the world could not be reconciled with any form of gradualist politics. The distance between the ideal and the real proved to be unbridgeable for Benjamin and for others sharing his commitment to radical transformation. The consequence was that those seeking revolutionary change and those willing to work within the system for reform failed to find common ground. This factionalism on the left contributed to the triumph of fascism.

Following the First World War, the left in Germany was unable to combine against the far right, which exploited conditions of massive joblessness and economic desperation. The global financial crisis that began in the late 1920’s was even more devastating in Germany than it was in the United States. Then as now, affluence coexisted more or less comfortably with homelessness.

That contribution cannot be blamed entirely on the repudiation of social democracy by the far left, however. For their critique of the Weimar Republic was in some measure a telling one. The Republic was likely to fail, they believed, because the enabling conditions for authentic democracy were not in place. Their insight was that isolated individuals, connected to one another only by the rules of “the free market” – with no shared purpose or meaning – cannot be expected to cooperate to build a just and caring society. Benjamin and those like-minded disagreed with what they took to be a blind social democratic faith in historical progress, guaranteed by ever-advancing technology.

Such political complacency, in Benjamin’s view, left the working classes vulnerable to recruitment into a fascist movement that deploys “great ceremonial processions, giant rallies, and mass sporting events, and war, all of which are now fed into the camera.” The Weimar Republic was undermined by the very technologies of mass communication that social democrats lauded for their liberating potential.

Then and Now. Benjamin’s account of politics-as-spectacle remains persuasive today. An authoritarian leader’s self-confidence and charisma create a circle of inclusion within which followers are captured by affirmation of their grievances. These grievances are often cast in racist terms, caught up in hatred of the other. But they may also express the resentment and humiliation of individuals who feel left behind and invalidated by the economy and the culture. In brief, an effective progressive movement has to speak authentically to the deep issues that the right exploits.

Can we find a better path than the one taken by Europe in the 1920s and 30s? It’s true that today’s problems – poverty, racism, disease, militarism, on-going exploitation of the Global South, and a planet hurtling toward climate catastrophe – look as daunting and intractable as those of the past. Yet it is clear also that the potential for solving these problems is in place: we have all the resources that are needed to move the world in a different direction. Consider what could be accomplished if we were, for example, to redirect the world’s military expenditures (over 2 trillion dollars annually) to the work of converting “swords to ploughshares.” Or if we were to implement the Global Marshall Plan proposed by Tikkun and former Democratic Congressman Keith Ellison to reduce domestic and world poverty.

Our political approach can learn from the achievements as well as the mistakes of the past. Although the Weimar Republic was brought to an end in 1933, its progressive policies found new expression following World War II when forces on the left regrouped and were elected to power in Germany, in Nordic countries, and elsewhere. Yes, post-war European social democracy was deficient in ways that critics like Walter Benjamin had pointed out – it fell far short of building a just and loving world – but it did take steps in that direction. Here in the United States, the New Deal in the 1930s, followed by the Civil Rights Movement and other popular movements born during the 1960s “kept hope alive.” At their best, labor unions, religious communities, and the Democratic Party sought to unite people of diverse interests and backgrounds behind a shared vision of the common good. This “big tent” approach is needed today too. History is still waiting for us to create the relationships – across the generations, across boundaries of every kind – that will permit Benjamin’s angel at last to take wing.