Editor’s Note: The following article is appearing in the upcoming issue of Tikkun magazine. To read all the other wonderful articles, please subscribe here.

On April 19, 1506, a pogrom broke out in Lisbon, Portugal, led by Dominican priests shouting “Death to the Jews!” and “Death to the heretics!” Rioters following these fanatical churchmen through the city streets ended up murdering some two thousand New Christians, Portuguese Jews who’d been forcibly baptised in a mass conversion nine years earlier. Their bodies were dragged to the main square that is still at the heart of the Portuguese capital – the Rossio – and burnt in two huge pyres in front of the Dominican church. Wood for turning them to ash was paid for by sailors visiting from the north of Europe, undoubtedly hoping for an unforgettable spectacle to highlight their stay.

I discovered this crime against humanity in 1990, while researching daily life in Lisbon in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, but when I asked my Portuguese friends what they knew about the massacre, they all replied, “What massacre? What are you talking about?”

I soon discovered that the pogrom wasn’t mentioned in Portuguese schoolbooks or even in standard reference works about Portuguese history. The two thousand murdered New Christians – between a third and a half of the city’s population of forcibly converted Jews – had been successfully erased from both individual and collective memory.

Feeling outraged, I decided to make the pogrom the background for the novel I was planning about a Jewish manuscript illuminator living in the Portuguese capital. In such ways throughout my life, I have learned that I have a deeply subversive personality; it gives me a sense of accomplishment to write of events that those with economic and political power would prefer to whitewash or forget.

The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon ended up telling the story of Berekiah Zarco, a bright and studious young New Christian who lives through the Lisbon Massacre of 1506 only to discover that his beloved Uncle Abraham, his spiritual mentor, has been murdered in the family cellar. While beset by grief and despair – and with his childhood friend Farid by his side – Berekiah decides to try to track down the killer and seek revenge. But as a kabbalist interested in the symbolic significance of events, he grows far more interested in what his uncle’s murder and the pogrom mean for his family, the New Christians of Portugal, all of humanity and even for God. Berekiah offers the reader his own interpretation on the last page of the novel and his words give the narrative an unexpected and chilling significance.

The novel took me a year to research and two years to write, and I did my best to create a narrative in the kabbalistic tradition – with different levels of meaning that readers must discover and interpret for themselves. At its most accessible level, The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon is a classic locked-door mystery, but it is also an account of the spiritual journey of the narrator and – I hope – a great deal else.

As sometimes happens when writers take on projects that challenge official history, I found it impossible to find a publisher. Over the course two years, my literary agent sent my manuscript to twenty-four American publishing houses and all of them turned it down. The great majority of editors acknowledged that I’d written a dramatic and insightful book, but they also told my agent that a novel set in Portugal in 1506 had no chance of selling to American readers. One editor at a well-known New York publishing house added that he’d already bought his “Jew book” for the year. Although I was appalled by his word choice, his honesty helped me understand my failure to find a publisher, since it clearly implied that editors maintained quotas. For all I know, even in 2019, such unspoken limits may exist for fiction with Jewish protagonists, as well as those featuring characters who are African-American, gay, Asian-American or members of any other ethnic or sexual minority.

The twenty-four rejection letters I received left me depressed and disoriented. My literary agent gave up trying to sell rights to the novel. Soon afterward, we parted ways.

By that time – 1994 – my long-time partner Alex and I had moved from the San Francisco Bay Area to Porto, Portugal, where I was teaching college journalism classes. I spent much of my free time in a haze of despair, wondering what I ought to do with my life, since I obviously wasn’t going to become a novelist.

A crazy idea saved me: why not show the manuscript to a Portuguese publisher? After all, the book was set in Lisbon and all the main characters were Portuguese.

I asked two writer acquaintances of mine for the names of reputable publishers and called up the only editor who appeared on both lists – Maria da Piedade Ferreira, head of a small publishing house called Quetzal Editores. In my pidgin Portuguese, I described the story to her, and she agreed that I could send her the manuscript. Three months passed without a response, however. When I summoned my courage to call again, she asked for me to come down to Lisbon – three hours by train from Porto – and talk with her. Two days later, when I arrived at her office, the first thing she said was, “What would you like to see on the cover?”

At the time, my Portuguese was poor and I thought I’d misheard her question. “Does that mean you want to publish my book?” I asked.

She smiled reassuringly. “Yes, we loved it,” she said.

I don’t remember anything else about the rest of our conversation because I was dizzy with excitement. I cried on the train back to Porto.

As the publishing date approached, Maria da Piedade warned me that my novel might not sell more than a few dozen copies. She feared that a great many potential readers would resent me, a foreigner, for exposing a crime against humanity committed in Portugal and nearly completely forgotten. What’s more, it was a pogrom fomented by Dominican priests and a great many potential readers would be practicing Catholics.

Unexpectedly, The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon reached number one on the bestseller list two weeks after its release. Why? In retrospect, I think that readers were curious about Portuguese-Jewish history, a topic that had been taboo in the country prior to the 1974 Portuguese Revolution and the development of a stable democracy. Prior to the Revolution, Portugal had been a repressive, right-wing dictatorship for nearly fifty years.

And so my career as a writer began in a unique way, with my first novel published originally in a foreign language.

Thanks to the book’s success in Portugal, I was able to find a new literary agent, and she was able to sell rights in Italy, Brazil, Germany and France. The American publishers to whom we sent the book turned the book down, however – some for a second time. But we were later able to sell rights to a good independent press in New York as well as a promising fledgling publisher in England. Eventually, the book became a bestseller in both countries. The novel has now been translated into twenty-three languages and has taken me on book tours around the world. In Portugal, where a bestseller usually sells about 5,000 copies, it has sold nearly 100,000 copies and changed an entire nation’s outlook on its own Jewish history.

More important than the book’s commercial success, however, is what it taught me: that I cherish the chance to write about people whose voices have been systematically silenced. In Portugal, where I have become a well-known writer, I am often asked to talk at schools and libraries, and one of the talks I most like to give is entitled, “Speaking for the Silenced.” Over the past twenty years, I’ve discovered that writing from the perspective of people who have been systematically persecuted, brutalized and forgotten gives me the energy – the slow burn of anger – that I need to keep me going over the two to three years it takes me to write a novel. It also makes me feel as if I’m fighting on the right side of history, which seems the best possible place to be.

In four of my subsequent novels I’ve written about different branches and generations of the Zarco family that I introduced in The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon. My aim has been to create what I call my Sephardic Cycle, a series of independent novels – to be read in any order – that explore the lives of men and women in the far-ranging Sephardic diaspora, which ranges from the Brazil and the Caribbean islands all the way to India.

As the saying goes, no good deed goes unpunished, and although these books have been generally well received in Portugal and England, I’ve often had great difficulty publishing them in America and other countries, and I’ve also gotten my share of personal attacks and hate mail.

The book that earned me the most resentment, from readers as far away as India, was Guardian of the Dawn, which explored how the Portuguese exported its Inquisition to Goa, a colony on the Malabar coast, about 250 miles south of Mumbai.

In Portugal itself, the Inquisition was first introduced in 1536. Its purpose? To persecute Jews who’d been forced to convert to Christianity in 1497. (Although New Christian is the accepted term for these unfortunate victims of religious intolerance, an epithet used in Portugal for many centuries was Marrano, which, according to historians, originally meant swine.)

Any New Christian suspected of continuing to practice his or her traditional faith in secret would be arrested by the Inquisition, interrogated and tortured. No infraction was too small to incur the wrath of this religious dictatorship. For instance, a converted Jew could end up in prison for simply whispering a Hebrew prayer. Or for cleaning his or her house on Friday afternoon, before the start of the Sabbath. The aim of the torturers was to compel their victims to give up the names of their friends and family members who might also be practicing Judaism in secret.

Prisoners often spent two years or more in small, nearly lightless cells in special Inquisitorial prisons. If they refused to accept Jesus as the Messiah and make a full confession of their Jewish practices – even if they had become, in fact, faithful Catholics – they would be burnt at the stake in a public ceremony known as an auto-da-fé, meaning act of faith.

Despite the risks of practicing Judaism in secret, the most tenacious New Christians continued to do so. Tens of thousands of them were imprisoned and tortured all the way up to the 1770s, when the Inquisition was finally dismantled.

Many thousands also fled whenever possible to Turkey, Italy, Morocco and a number of other countries where they could openly practice Judaism, creating the Sephardic diaspora. The great Sephardic communities of cities such as Istanbul, Salonika, Ferrara and later Amsterdam and London boasted many learned philosophers, physicians, scientists and financiers who continued to speak Portuguese at home, among them Baruch Spinoza, Uriel da Costa, Gracia Nasi and Amato Lusitano.

In 1560, Portugal imposed this same religious dictatorship on their colonies in India, which meant that a converted Hindu could be locked up for something as simple as making an offering in their home to Ganesha, the elephant-headed God of Wisdom, or to any other deity in the Hindu pantheon.

In Goa, tens of thousands of converted Hindus and their descendants were arrested and tortured – and hundreds burnt alive – by the Inquisition from 1560 to 1820.

The Inquisition was also a diabolically effective money-making scam, since all the assets of its victims were confiscated and given to the Church.

Guardian of the Dawn became the story of a Tiago Zarco, a great-grandson of Berekiah Zarco, the narrator of The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon. When Tiago’s father – a manuscript illuminator for the Sultan of Bijapur – is arrested on a visit to Goa, Tiago tries and fails to save him and ends up imprisoned himself. Years later, upon his release, he takes his revenge, but it leads to unforeseen – and tragic – consequences.

After the novel was published, I received a number of hate-filled letters from Portugal and India, partly because I’d given an interview to a Lisbon newspaper in which I’d said that canonizing Francis Xavier – the Spanish missionary who petitioned the Portuguese king to establish the Inquisition in Goa – was like conferring sainthood on Goebbels or Göring. A rash declaration? Possibly so, but it’s still what I believe.

Most troubling of all, two correspondents from Goa cursed me as a “filthy Jew” and told me that my book was one big lie; they claimed that the Portuguese hadn’t exported the Inquisition to its Indian colonies. After reading their enraged letters, I realized that there are Indian Catholics who deny the existence of the Inquisition in India, much as there are some sick and dishonest individuals who deny the existence of the Holocaust.

Another of my books about descendants of Berekiah Zarco, The Seventh Gate, also earned me hate mail, this time from neo-Nazis in America and England. It’s a novel that explores a crime against humanity that few people even today seem to want to know about: Hitler’s sterilization and murder of up to 300,000 disabled people. The narrator, Sophie Riedesel, is a young Christian woman whose younger brother, Hansi, is autistic. When her beloved Berlin is taken over by the Nazis, she vows to do everything she can to undermine their anti-Semitic regulations and protect her brother from their plans to sterilize him. To live up to her vow, she risks joining a clandestine resistance group called The Ring, headed by her elderly Jewish neighbour, Isaac Zarco.

Curiously, when I went to Stockholm and Gothenberg in 2008 to promote the Swedish edition of The Seventh Gate, the Swedish media refused to publish any reviews of my book or articles about my visit. According to my publisher, this was because Sweden had embarked on its own eugenics program to improve “racial purity” beginning in 1934. More than 60,000 individuals were sterilized with state approval, 90 percent of them women, and the program remained active until 1976. At the time I visited, the subject of eugenics was still largely taboo.

Despite all these difficulties, 99 percent of the thousands of letters and emails I have received over the past 23 years have been enormously positive and generous, and such feedback gives me the encouragement I need to keep going when a book of mine is rejected by a publisher or gets a negative review. The most supportive letters I’ve ever received? Very possibly the half a dozen messages I got from Israeli readers thanking me for The Search for Sana, which I published in England but for which I was unable to find a publisher in America. A number of editors there told me that they feared a backlash because it’s a novel that portrays Israelis and Palestinians in ways that we don’t generally see in the media. The Search for Sana is about two women – Sana, a Palestinian, and Helena, an Israeli – who grow up in the same neighbourhood in Haifa and whose wonderful friendship is undermined and finally destroyed by the conflict between the two peoples.

One of the messages I received was from an Israeli named Dana:

“My journey through your book was full of pain, disappointment, anger and frustration, but I came out the other end feeling strong in my convictions, and strong in my place in the world. I identified with all your characters – with Sana, Helena, Samuel, Rosa, Zeinab, Mahmoud and Jamal. I realized I was a human being and that is what I should hold on to, and let go of any other identities. You have told the story of the Israeli-Palestinian tragedy in the most honest way. You have put on paper everything I was carrying within me. I will no longer have to explain, I will just point people to your book.”

I’ll also always treasure the three emails I received from Holocaust survivors who thanked me for The Warsaw Anagrams, the story of an elderly Jewish psychiatrist living with his niece, Stefa, in the Warsaw ghetto and whose life comes undone when her young son, Adam, is murdered. One elderly survivor who grew up just outside the Polish capital wrote: “I was 14 when I and my family entered the Warsaw Ghetto. I was 16 when I escaped and was hiding in Poland for the rest of the war. Unfortunately the rest of my family did not survive. I was very moved by the details of your descriptions of daily life in the ghetto, which reminded me of many of my own experiences. I cried on reading the description of Stefa’s behavior after the discovery of Adam’s body. She and the other characters were so alive to me that I felt like I knew them all. I was so emotionally involved that when I finished reading the book, I forgot that they lived 70 years ago and would now all be dead. Thank you for your obvious emotional connection to the Holocaust.”

. One elderly survivor who grew up just outside the Polish capital wrote: “I was 14 when I and my family entered the Warsaw Ghetto. I was 16 when I escaped and was hiding in Poland for the rest of the war. Unfortunately the rest of my family did not survive. I was very moved by the details of your descriptions of daily life in the ghetto, which reminded me of many of my own experiences. I cried on reading the description of Stefa’s behavior after the discovery of Adam’s body. She and the other characters were so alive to me that I felt like I knew them all. I was so emotionally involved that when I finished reading the book, I forgot that they lived 70 years ago and would now all be dead. Thank you for your obvious emotional connection to the Holocaust.”

Probably because I never dreamed I’d find readers in faraway places, it gives me a special thrill to receive emails and letters that come from places like Australia, Brazil and South Africa. A message sent me by a Turkish young woman named Eda is particularly dear to me because it confirmed that novels can change the lives of persons whom I’ll probably never meet. The book she’d read, Hunting Midnight, tells the story of a friendship between a Portuguese-Scottish young boy, John Zarco, and an African Bushman (San) nicknamed Midnight who comes to live in his home in Porto in the early Nineteenth Century. Through these two characters, the book explores the disastrous spiritual and emotional effect of slavery on individual lives and society as a whole. Eda wrote, “I’m a fifteen year old Turkish girl. I am reading one of your books, ‘Hunting Midnight.’ Let me tell you it’s the most impressive novel I’ve ever read. The book actually changed my life, my vision. Even a history book couldn’t teach me this much things while giving me so much pleasure. Before reading your novel, I was a little tired of hearing about Jews and blacks. However, I thank God for the day I saw and bought your book.”

You might think that writing a number of bestselling and well-reviewed novels over the past twenty-three years would make it relatively easy for me to secure good publishers in America and England, but finding takers for my latest novel, The Gospel According to Lazarus, proved quite difficult. This novel expands on the story of Lazarus and his resurrection that is told in the Gospel of John.

One of my goals in the book, which is narrated by Lazarus himself, was to give back to him and Jesus their Judaism. In consequence, Jesus is known by his Hebrew name Yeshua ben Yosef and Lazarus is Eliezer ben Natan. Additionally, I have characterized Yeshua as a Galilean mystic and healer very much in keeping with his times.

The Gospel According to Lazarus is a story about the sacrifices we make to help the people we love most and how we find the courage to go on after suffering a deep trauma. It begins with Eliezer awakening in his stone-cut tomb, unsure of where he is and disoriented. Worst of all, his faith has been shattered because he remembers nothing of an afterlife. Fragile and vulnerable – caught between life and death – he turns for help to Yeshua, and the two men embark on a new phase of their long friendship.

In flashbacks, we learn of Eliezer’s first meeting with Yeshua – during their boyhood in Nazareth – and discover how he came to earn his friend’s trust and gratitude. Back in the present time – during Passion Week – Yeshua tells him, however, that their meeting as young boys was no accident and offers an astonishing explanation for why he brought them together.

After Yeshua’s arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane, Eliezer concludes that his whole life may have been a test for this chance to save his beloved friend from crucifixion. Only many years later, however – after Eliezer has been forced to flee Jerusalem – does he begin to understand the true role that he played in Yeshua’s life.

I grew passionate about this project in part because it has long seemed to me that both Christian and Jewish thinkers have been unfair in their characterizations of Yeshua ben Yosef. In particular, the anti-Semitic interpretations of the Gospels often disseminated by Christian religious leaders has had disastrous consequences for Jewish communities throughout the world and continues to create hatred of Jews in countries such as Poland and Hungary. Such interpretations also seem completely inaccurate to me because they fail to recognize that Yeshua was a Jewish spiritual leader who embraced the practices and beliefs of his people. As for Jewish thinkers and religious authorities, few of them have been willing to embrace Yeshua as a spiritual leader. As far as I know, the only renowned Jewish philosopher who called for Yeshua to be incorporated into the Jewish canon was Martin Buber.

Nowhere in the Gospel of John is there any indication that Yeshua had any intention of renouncing his Judaism. So presenting him as a Galilean mystic and healer who makes use of the spiritual practices of Judaism as they were understood some two thousand years ago seemed to me an intellectually sound and worthwhile endeavour. Will American readers be willing to accept this departure from traditional Christian and Jewish readings of Yeshua’s mission? I don’t have any crystal ball, of course, but I’ve already received a number of emails from readers in England – where the novel was released earlier – telling me my narrative freed them from their pre-conceived notions about Yeshua and Eliezer and gave them a fresh outlook on ancient Judaism and the beginnings of Christianity.

Postscript:

Back in the fall of 2005, as the 500th anniversary of the Lisbon Massacre of 1506 approached, I asked Jewish community members how they were planning to commemorate this tragic and influential event. When they told me that they had no plans to do so, I offered to brainstorm with them about possibilities or participate in any event they organized.

Jewish leaders ended up holding a solemn ceremony at a downtown hotel on April 29, 2006. I spoke there about the importance of remembering those who’ve been crushed by religious and ethnic intolerance, whether Jews in Portugal, Native Americans in America, Aboriginals in Australia or any other people in any other country. And why? In my view, in order to create an ethos of justice and fairness and prevent future crimes against humanity. On a more personal note, I also spoke of how gratifying it has been for me to give voice to people who have been systematically silenced.

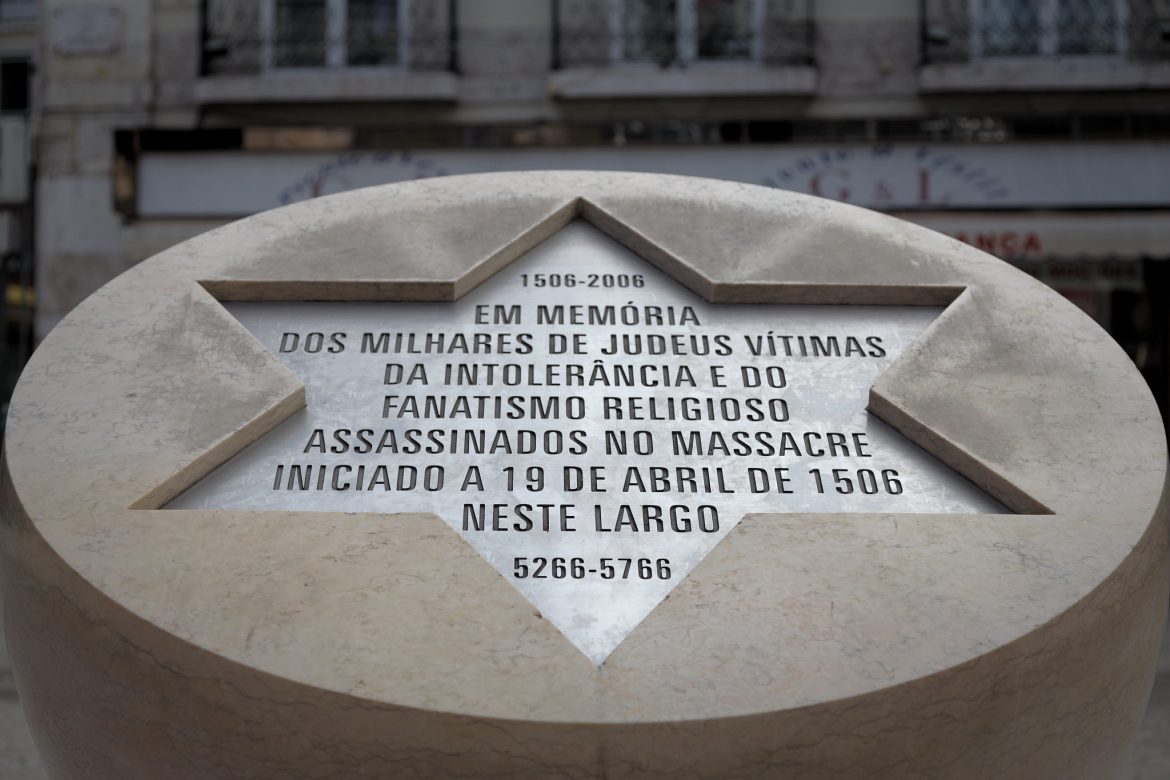

Some months later, a monument to the murdered Jews was placed in a small square in front of the Dominican Church where the Lisbon Massacre began. I was very moved when officials from Lisbon City Hall told me the monument would never have been put up without the attention I drew to pogrom in my novel, The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon.

In recent years, the monument has become a place of pilgrimage for Jewish visitors and others who wish to honor the memory of the two thousand forcibly converted Jews whose bodies were burnt in front of the Dominican Church.

In 2014, the Portuguese government also approved a project for which I had long lobbied: to give citizenship to Sephardic Jews living anywhere in the world who are able to provide evidence that their ancestors were from Portugal. As of May of this year, more than seven thousand Jews from Israel, Turkey, Brazil and a number of other countries had already had their applications approved and been awarded the nationality of their ancestors – men, women and children who had been tortured and murdered by the Inquisition or forced to flee religious persecution to other countries.

It is false the claim that ot os not studied in school. I did.

Thank you for your sad, brilliant expose of religious intolerance. It is a world-wide problem, to be sure. But it is especially a Christian problem. I do see how much Jews and Christians are reaching out to each other, and in the US, at least, including also Muslims, but the problem is ongoing with fits and starts.

I pray your work will open the eyes of the religiously motivated who fall back on anti-semitic lies to justify their hatred of Jews. Please keep writing.