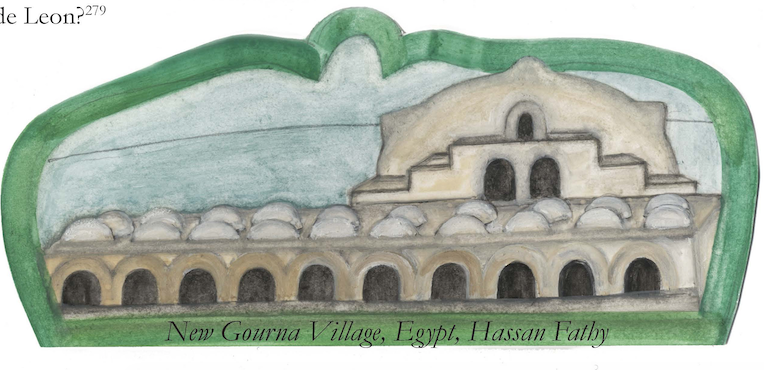

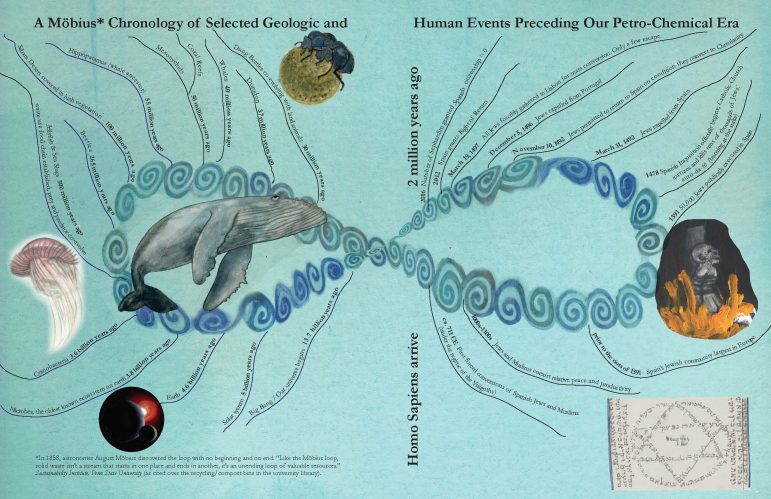

Paintings by Micaela Amateau Amato from Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era

[Editor’s Note: The Torah calls for a year of rest for the Earth for humans and animals. It’s called Shmita and it happens every 7th year. — Rabbi Michael Lerner rabbilerner.tikkun@gmail.com]

In the framework of our current Shmita Year, “Sacred Attunement: Shmita as Cultural Biomimicry” explores the Hebrew concepts of selah (pause, including a practice of decolonizing our relationship to homogenizing linear-time) and mitzrayim (narrowness or constriction—originally referring to our flight from Egypt, but relevant now in how we get stuck in our habits of assumptions, refusing to ask questions, refusing to seek connections, refusing to witness our interdependencies—convergences that set the stage for disaster capitalism [1]). Scott Gilbert reminds us that making war is …’us’ against ‘them.’… On the other hand, Shalom …means to be in proper relationship, friendly reciprocity. Similarly, the Arabic word salaam also connotes being safe, secure, and forgiven. …Negotiation and prevention are difficult and take enormous amounts of humility, patience and creativity. Peace requires a pause. It is the never-completed process of what theologian Catherine Keller has called ‘respectful agonism.’ [2] Let us begin our peace-pause negotiations with and through Shmita. The Shmita Year of the Hebrew calendar reflects a cycle analogous to our weekly Sabbath—once every seven years instead of every seven days—Shmita is an exponential Shabbat.

There are many ways we can explore Shmita: the Year of Release or Letting Go, an opportunity to reimagine our daily lives that fosters creativity and invites spiritual, intellectual collective risk-taking. Shmita invites each of us to restore balance to the land, to re-examine our relationship with the earth around us, with the Divine, with our bodies and psyches, with one another individually and in community. We re-examine our relationship to money, accumulation, generosity. In the Shmita year, we commit to rest in conjunction with multiple ecosystems. It reminds us of Winona LaDuke’s proclamation: “We are land.”

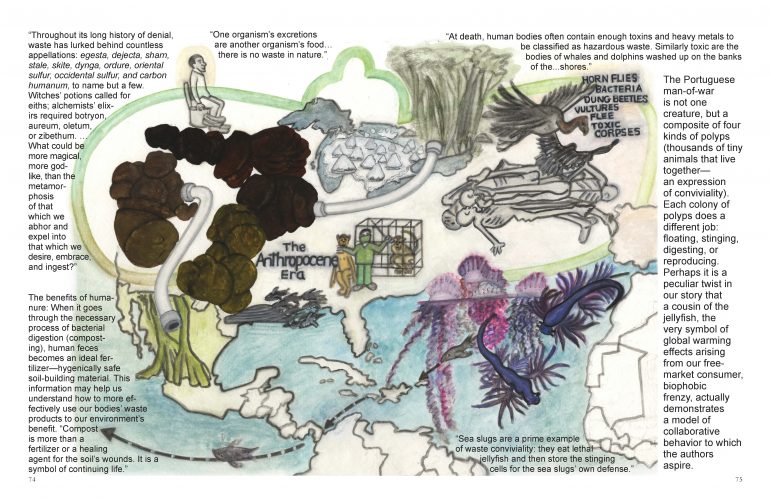

Shmita reminds us to shift from Anthropocentric habits to Biocentric behaviors and choices; to release both humans and the earth from debt (including financial, emotional, structural). During the Shmita year we take down gates, fences—we let go of our addiction to personal property. Communal ownership becomes the norm. The concept of ownership itself is re-evaluated. [3] Gleaning becomes an integral form of shared economics and hospitality—a sacred economics reflecting our Sephardic history of Convivencia (conviviality—referring to the Golden Age of Spain during which Muslim and Jewish literature, science, and arts flourished in relation to each other). Convivencia can be framed as the apotheosis of non-binary relationships—those antagonistic categories from our initial sensory thought-experiment. Economic justice is integral to this Shmita consciousness. Consumption practices are re-evaluated; and, as Jeremy Bernstein says, Shmita “gives the world a rest from us.” [4]

In contrast to our industrial civilization’s obsession with unlimited economic and technological growth, Arthur Waskow urges us to embody a spiritual and politically radical pulsating economy—a Shmita rhythm that invites a pulse shifting between growth and rest; [5] an opportunity to rethink the vastness of our economy. Like the word ecology, economy comes from oikos, meaning home. This sense of “home” includes evolving an embodied pause. This fertility of the in-between invokes personal, community, and ecological healing—a healing with our lands as we pause to question our habits and recreate our relationships. “Sacred Attunement: Shmita as Cultural Biomimicry” will hopefully inspire you to explore the beauty of the fertility of the pause—where we can begin to find allies in unexpected places.

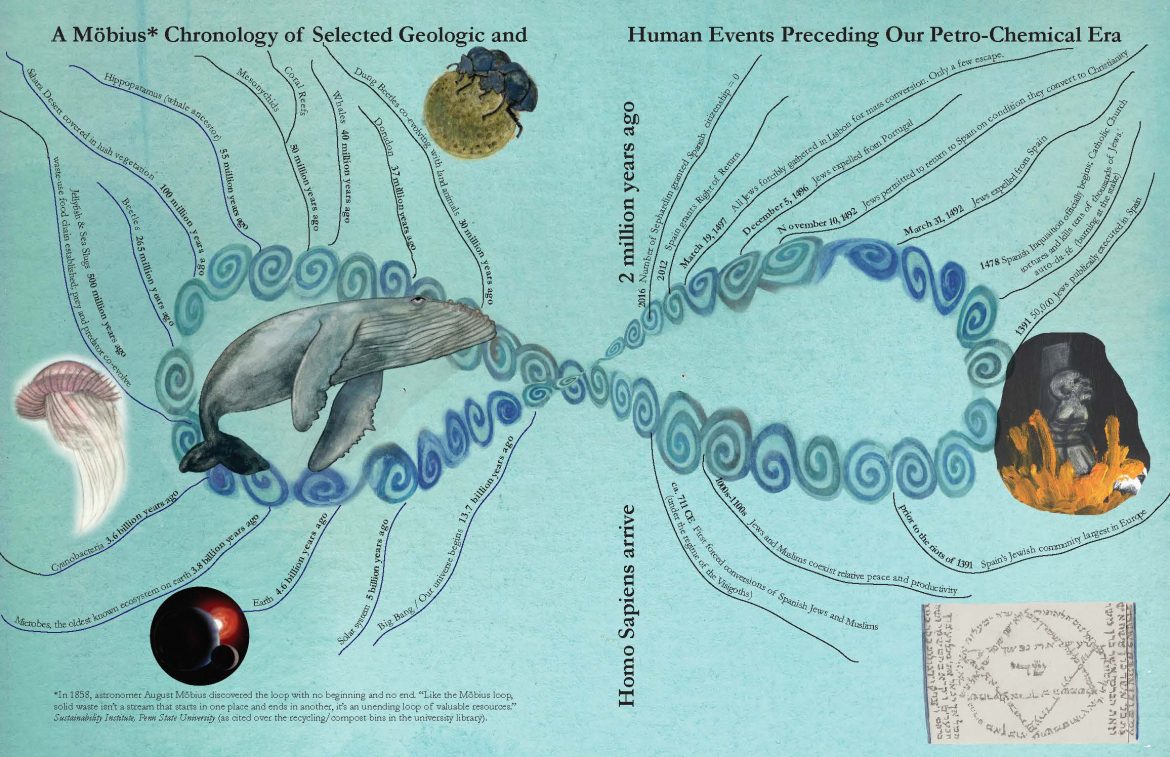

Just as practicing Shabbat is a practice of civil disobedience—choosing to not participate in the relentless hyper-industrialist capitalist drive to do more, radical rest, Shmita, also debunks the status-quo—the machine of our everyday taken-for-granted violence. This commitment to Shabbat-consciousness requires that we completely reexamine the interrelationships among our social, economic, and land-based infrastructures. Reminiscent of Brian Swimme and Thomas Berry’s explorations of “Deep Time”,[6] Abraham Joshua Heschel resets our sensitivity to time and space: “Six days a week we live under the tyranny of things of space; on the Sabbath we try to become attuned to the holiness in time. …to turn from the results of creation to the mystery of creation: from the world of creation to the creation of the world.” Emancipation from “enslavement to things”[7] is a foundation for the biocentric Slow Movement.

Just as the profound Jewish tradition of Shmita can help lead us through many of our contemporary crises, models of rest from nature can also help guide us. In order for us to practice tikkun olam (repair of the world), I am suggesting we embody our Ancient Traditions, our Ancestral Teachings, as well as relationships found within biological processes and our Natural-world.

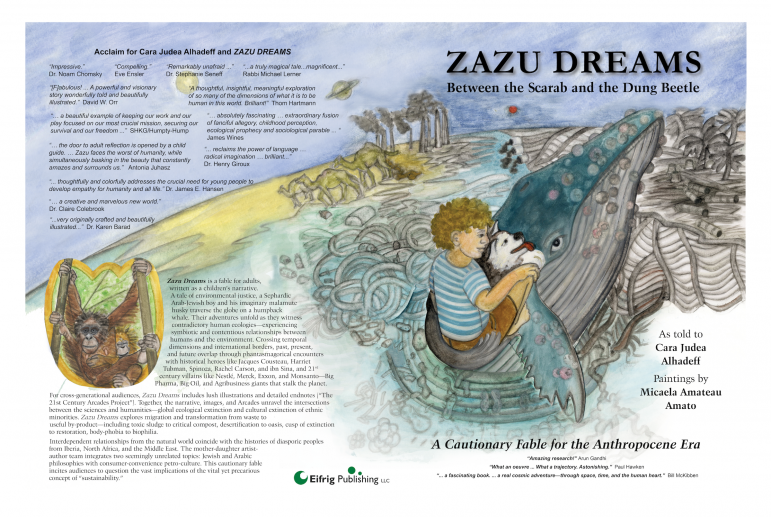

My cross-cultural, Jewish histories and philosophies, climate justice book, Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era, explores these lived intersections. I connect mutual justice and shared consciousness that, for hundreds of generations throughout the Middle East, the Caribbean, and India, have nourished coexistence among humans and between humans and non-human nature. All of the images I am sharing today come from Zazu Dreams. When we learn how to internalize the tradition of Shmita—when we learn how to internalize deep listening and deep receiving as a result of practicing the cycles of imbibing and digesting, we develop an ethic of empathy that urges us to expand our sense of play, vulnerability, and intuition—sensibilities that come from integrated rest and respecting our bodies’ and the earth’s natural cycles. Rabbi Michael Lerner illuminates the history and practice of Jewish Renewal as a reflection of this profound sense of care.[8] Such deep, culturally-sanctioned empathy emphasizes a re-spiritualization of nature that embraces community and self-regulatory equilibriums. Like the metabolism of the human body and the earth’s tendency towards homeostasis, the metabolism of our culture must be rejuvenated as a relational organism.

In addition to inviting us to practice a pause in our personal lives as we break down false binaries, the question I am asking is: What if adaptation to climate crisis didn’t imply mass-consumer reactionism to climate emergency—buying more in order to protect ourselves from the natural world; what if adaptation functioned as a reflection of what Nature is already teaching us—if only we were willing to listen. The “we” to whom I am referring are those of us dominator cultures/dominator civilizations characterized by a middle-class standard of living that depends upon the exploited labor of others.

Below, I present a warning, and then a proposition:

We know that commercial mechanisms that supposedly reduce our stress and increase our leisure time actually eliminate natural cycles—our body never gets a break, our land never gets a break—no crop rotation, no Shmita, no pause. When we don’t practice Shmita, our bodies, our human-made societies, and our natural environments get inflamed—our bodies and our earth are on fire. Inflammation happens when we get stuck in an antagonistic us vs. them mentality. Our modern economic model of efficiency is based on further accelerating our speed-obsessed culture. Heschel elucidates: “……Sabbath is not for the purpose of enhancing the efficiency of [man’s] work.[9] We maintain economies of scale by actually using more “resources.” Vandana Shiva, as so many indigenous activists, reminds us that the techno-industrial concept of “resources” itself is rooted in capitalist-colonialist histories. Shiva decries:

Resource implied an ancient idea about the relationship between humans and nature – that the earth bestows gifts on humans who, in turn, are well-advised to show diligence in order not to suffocate her generosity. In early modern times, “resource” therefore suggested reciprocity along with regeneration. With the advent of industrialism and colonialism, however, a conceptual break occurred. ‘Natural resources’ became those parts of nature that were required as inputs for industrial production and colonial trade.[10]

We build bigger houses, use more electricity, we build cars that reduce the cost of driving and lower barriers to commerce, we consume more products made with toxic materials (too often in other countries using slave and child labor). In the name of efficiency, we are suffocating in Jevons paradox: In 1865 (at the age of 29) William Stanley Jevons wrote The Coal Question in which he stated: “It is a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.”

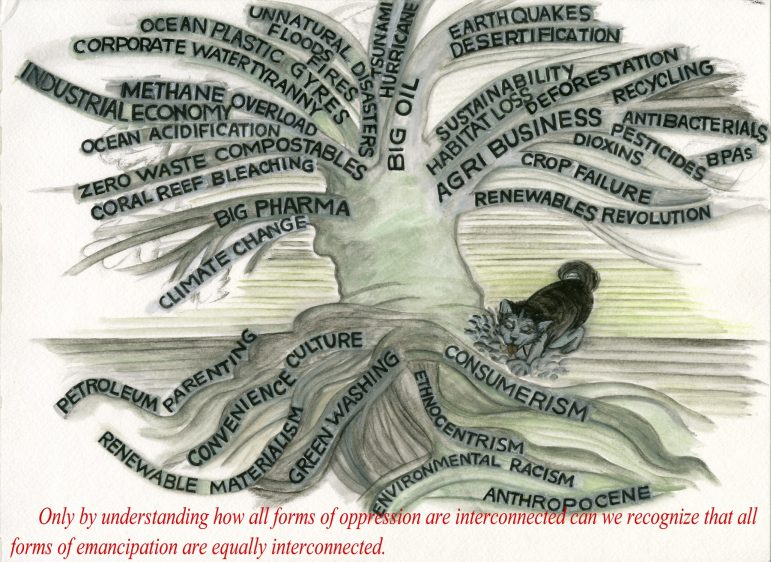

Jevons paradox of efficiency is central to what I believe to be a common misconception of the potential of Shmita. I’ve been attending dozens of Shmita events hosted by Jewish environmentalists. Unfortunately, “renewable” energies have come up many times as an example of Shmita. I suggest quite the opposite. At this juncture of geopolitical, ecological, social, and health catastrophes, we must critically question the greening-of-capitalism: clean/green solutions such as the erroneously-named Renewable Energies Revolution. In climate crisis discussion, too much attention is on institutional band-aids, technological fixes, and consumer distraction (frequently disseminated through greenwashing). For example, on the surface, “renewable” energy appears to offer critical shifts toward an ecologically, economically, and ethically sound society. However, “renewable” energies, the “green economy,” and “clean technology” have become radical diversions from the actual crises that extractive industrial-capitalism generate.

The roots and implications of these perceived solutions to climate crisis may unintentionally perpetuate ecological devastation and global wealth inequities, actually diverting us from establishing long-term, regenerative infrastructures—capitalist “solutions” to a capitalist problem: climate chaos. Perhaps temporarily abated, they ultimately conserve the original crisis. However well-intentioned, like the misleading construct of “efficiency,” these supposed alternatives to global petroculture perpetuate violence of wasteful behavior and destructive infrastructures. As with climate-crisis injustices, communities that are the least responsible for converging calamities are the hardest hit. For example, the characters in Zazu Dreams witness social and environmental costs of subjugating others through fossil-fuel-addictions and their ostensible “green” replacements. Both carbon-intensive extractive economies are dependent on people and objects-reduced-to-“resources”-as-disposable. In contrast with this racial capitalism, we can revisit Lerner’s Jewish Renewal: a practice of attuning ourselves to the voice of God as an antidote to such xenophobia.

Fallacious “renewable” energies, like fossil fuels, are rooted in economic growth. In order to reimagine cross-cultural and cross-species community models of lifestyle activism, I am suggesting that we all question the underpinning values of replacing one form of corporate tyranny—fossil-fuel economies—with another—“renewables”—that ironically and in fact not ironically continue to depend on those very fossil-fuel economies. Because of the dependency on extractive-mining, fossil-fuel based infrastructures, and e-waste, focusing on spurious “renewable” energies as a solution for our climate crisis maintains the illusion of our separation from ourselves and from nature.

In our petroleum-pharmaceutical-addicted cyber-world, our collusion with corporate and imperial forms of domination sustains our techno-euphoric race into a sanitized, hyper-electrified-5G future—this includes the Renewable Energies Revolution. What if we could learn from creatures that communicate using extraordinarily evolved sensitivity to their environment. This is where we can recognize and embody a practice Shmita. This is not a new proposition. For thousands of years, cultures across the globe have practiced this kind of cultural biomimicry. What if modern industrialized civilization like Big Telecom could adapt behaviors and infrastructures rooted in ancestral animism?

For example, if we embrace how our non-human kin learn, we can develop a healthier, more equitable world through co-relational infrastructures; we can remember that we are bioelectrical systems that use electrochemical activity and electrochemical signals to move through time and space —to adapt—to be in relation to the shifting worlds around us. This is the foundation for co-beneficial interrelationships. Non-hierarchical electrical communication patterns in nature can be used as models for human interactions as we evolve toward ecological justice.

This intimacy-based movement is rooted in spiritual practices and everyday-life choices. It resonates with geologian, Thomas Berry’s concept of the Ecozoic—in which humans share mutually beneficial relationships with the world around them. Intellectually, structurally, and spiritually, we integrate with our natural environment, rather than compete with it. Renouncing the Anthropocene as we shift into the Ecozoic Era means that we honor the sentient abilities (electromagnetic cellular consciousness) of animals, plants, trees and the organic intelligence of these non-humans, our kin. We all are by nature electrical beings—animated by our electromagnetic fields. This understanding intersects with Dr. Suzanne Simard’s (called “the Rachel Carson of our time”) research on the intimacy of how trees communicate through intricate webs of mycelium.[11]

Below are some Shmita-like models from Nature that all integrate a pulsating rhythmic cycle of a Pause that conserves energy. These models could help us reduce the usage of fossil-fuel generated heat sources and artificial cooling (air conditioning). If we were to apply these earth technologies as cultural biomimicry models we could recreate our entire architectural engineering and agricultural infrastructures. Ancestral animism from a variety of cultures could be our guide. For example, many plants enter a state of dormancy to protect themselves from both extreme cold (freeze) and extreme heat (drought).

A dormant tree secretes a sugary liquid that protects it from freezing inside. Tiny leaf blankets wrap around the tree buds. The tree pauses. Insect dormancy is called diapause, animal dormancy is called hibernation. Torpor is a short-term period of sleep during which animals reduce their body temperature to save energy. While hibernation and torpor are forms of co-existence with cold, estivation manifests as co-existence with heat. For example, during a drought, earthworms, mosquitos, land crabs, tortoises, and salamanders can go through estivation. Brumation is dormancy in reptiles and amphibians. Droughts can force crocodiles into brumation—they burrow into the side of a riverbank until the drought passes.

This kind of Interspecies consciousness invites us to learn passive solar architecture from cold-blooded animals who use the sun to help themselves keep warm and use the earth to help protect themselves from the sun. I’m proposing that we reflect on these animal cycles in the context of evolutionary biology and epigenetics.

During this period (rather than the traditional cycle of every seven years, think of Shmita cycles that may now become unpredictable because of climate crisis), certain plants, animals, and insects conserve their body fluids, cool down, slow their heart, and save energy. Chill, rest, prepare. This pause is not about eventually doing more, but about equilibrium. This pause allows us to deepen our vitality, practicing our sacred attunement to ourselves and the worlds around us. My 10-year old son, Zazu, calls this “Deep Noticing.”

In Silent Spring Rachel Carson reminds us: “There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature…” Through “deep noticing,” we can learn strategies to embrace this healing—developing self-care and community-care tools that revitalize health and racial equity in the face of the normalcy of unlimited growth. Throughout Zazu Dreams I refer to multiple manifestations of biomimicry—many of which are initiated by the US military. For example, engineers are applying beetle’s evolutionary strategies in designs for military infrared radiation detectors.[12] What if our educational institutions invested in these kinds of commitments to learn from nature?

One version we could apply is bioregionalism—focusing on the vitality of the locals. In his book Nation City, Rahm Emmanuel, the former mayor of Chicago explores cities as indispensable centers for paradigm shifts because of the smaller scale—less bureaucracy, less entangled infrastructure, and more potential for bi-partisan resource sharing.

Embodying Shmita values means genuinely practicing de-growth. If Jubilee is the great letting go, then we can see rest and renewal as a time for celebration, not deprivation or sacrifice. Sabbath itself maintains an ethos of self-restraint. As Waskow tells us, “restraint is not self-denial,” but an opportunity for joyful individual and community expression. Rest and renewal become integral to dignified living choices that develop work patterns rooted in equilibrium and creative collaboration. Ched Meyers from Sabbath Economics[13] reminds us that abundance is our divine gift and self-regulation is an appropriate response. He emphasizes the importance of moving beyond the doing / not-doing dichotomy, and instead practice an individual and collective recovery from industrial civilization. Similarly, in The Sabbath Heschel shares “Sabbath is the day on which we learn the art of surpassing civilization.” However, “renewable” energies are rooted in civilization.

I am suggesting that each of us practice environmental justice, community action through S.O.U.L. (Shared, Opportunity, Used, Local). Through an urgent commitment to creative-waste collaborations that focus on a S.O.U.L. framework, we can transform corporate-capitalism’s everyday violence—consumption and entitlement—creating a bridge between community action, infrastructural design, corporate accountability, policy reform, and individual response-ability. Fostering the advantages of working together across cultural, economic, and ethnic differences, we can offer how the concept of home (oikos—economy/ecology) can become a unifying goal.

Through dialogue and debate, we can bridge seemingly irreconcilable differences and intractable conflicts through active listening where people of diverse backgrounds can find allies in unexpected places. Our varied experiences and perspectives can nourish sustainable coalition building, and develop extraordinary resiliency and creativity necessary for

community. More than ever in history, it is essential to recognize our interconnectedness and our unity in diversity. Following models of Truth & Reconciliation conversations, growing relationships can help overcome fear that divide-and-conquer politics breed. Divide-and-conquer techniques can only be inflicted when individuals do not experience themselves as relational beings. A committed Jewish Renewal practice dematerializes such fear-induced illusions of separation. Rather than blaming and shaming and adhering to ‘us vs. them’ divisions, we recognize our commonalities and how we are all interdependent.

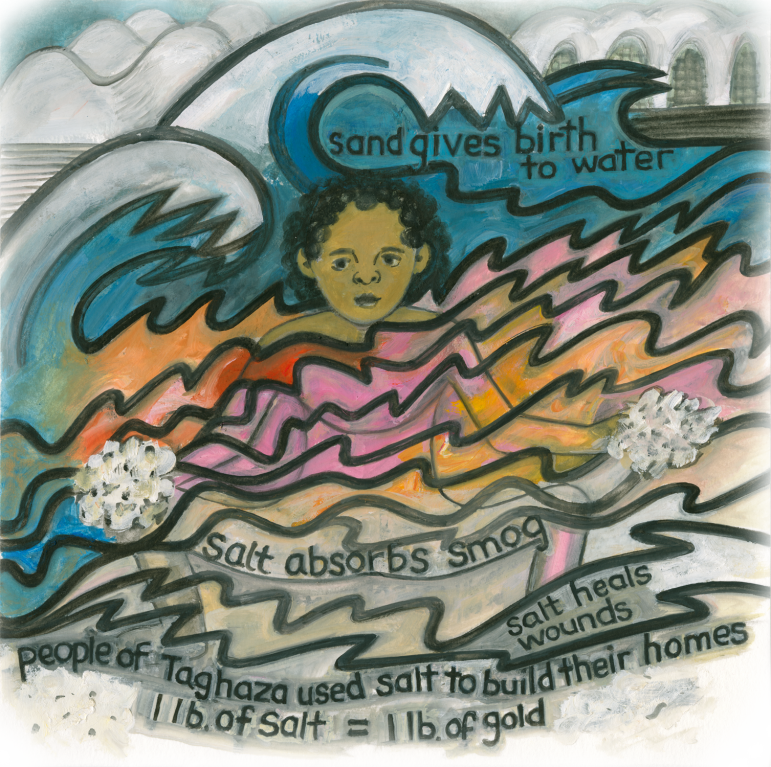

When we are clearly attuned with the space, time, and objects around us, we witness what is already here, how it can be used in surprising ways—once again referring to S.O.U.L.as a practice of equilibrium. As the physicist and cosmologist, Stephen Hawking’s idea, everything we need to know is already within us just waiting to be realized, Greta Thunberg urges us to remember that we already know how to solve our environmental crises. From this psycho-spiritual commitment, we can engage collaborative economic tools for biocultural transformation—a resistance to colonialist legacies of systemic economic oppression and extractive industries. A joyful, cross-cultural, interspecies approach to climate-crisis mitigation weaves simultaneous individual, community, and infrastructural accountability. This collective spiritual intelligence, this deep mindfulness, is a devotion to nonviolence—recognizing and nurturing the sacred in everyday objects. A devotion to repurposing objects, to constructing co-beneficial, regenerative infrastructural support systems is an antidote to industrialized convenience-culture. It is an embodiment of selah—pause.

Congruently, as we unlearn Mitzrayim and our internalized oppression of habituated obedience fulfilling the status quo, we can learn from waste-consuming creatures that co-exist with their environments. As a response to my own challenge of how to weave social justice and environmental ethics into our daily lives, my family and I bought a used school bus. Our repurposed tiny home is our personal embodiment of a Shmita-consciousness or Shmita-ethos. We shared our dreams of living in a tiny home that we would make ourselves using only reclaimed, repurposed materials and equipment. It took us 30 days and a total of $5,000 to transform the bus —saving it from its fate of being stripped, sold, and crushed. Our family brainstormed to change our habits, and we discovered unexpected solutions within the pause—a collaborative pause.

We felt like dung beetles that use others’ waste to build their home and feed their family, or like sea slugs that eat debris off the ocean floor. Like the humpback whale character in Zazu Dreams reminds us: “When humans throw things away, they’ve got to understand that there is no ‘away!’ Instead, we all must learn from waste-consuming creatures that co-exist with their environments.”

When we move beyond binaries, we inhabit the Pause. This Shmita-consciousness invokes a personal-political practice not only of letting go but simultaneously a practice of receptivity—being open to the unknown. These collaborations help identify and nourish being receptive to unpredictable solutions or alternatives to destructive normalcies. We can mutually develop skills to learn how to be receptive to a future we have not yet imagined. A future that may seem impossible.

Chapter Four in Zazu Dreams is entitled “…spooky action at a distance…” It highlights

Einstein’s reference to quantum entanglement—essentially, how all living things—from our microbiome to the macrocosmos—are utterly interwoven; and, explores the roots and implications of plastic pollution in the ocean. Zazu, the main character, gets entangled in the plastic gyre floating through the Pacific Ocean. One of the elements that saves him is his recollection of Jacques Cousteau who helps Zazu imagine the impossible: “The impossible missions are the only ones which succeed.”[14] I here conclude with a Ladino proverb that demonstrates the potential of moving beyond the status quo into an embodied practice of Shmita as sacred attunement: What the world thinks impossible can happens in a moment.

Lo que no acontece en un mundo, acontece en un punto.

Share on Social Media:

[1] “Coined most famously by Naomi Klein, disaster capitalism is ‘the way private industries spring up to directly profit from large-scale crises…[and] to push through policies that systematically deepen inequality, enrich elites, and undercut everyone else.’” Kristina I. Lizardy-Hajbi cited in “Disaster Capitalism in Puerto Rico: Resisting Colonialism,” in Shifting Climate – Shifting People, Miguel De La Torre, ed., Pilgrim Press: Cleveland, OH, 2021.

[2] .O, Curry, S., and Gilbert, S. F. 2021. Choosing life stories: Body as teacher. Mother Pelican Journal of Solidarity and Sustainability. http://www.pelicanweb.org/solisustv17n05page3.html

[3] See my Viscous Expectations: Justice, Vulnerability, The Ob-scene. State College, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press; (www.carajudea.com).

[4] The Jewish Calendar, Planet Earth, & the Climate Crisis

[6] Swimme and Berry, Universe Story: From the Primordial Flaring Forth to the Ecozoic Era–A Celebration of the Unfolding of the Cosmos. HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY: 1994. In his interview in The Sun, Swimme cites Heschel’s resistance to the Anthropocene: “Rabbi Abraham Joshua said that awe is the beginning of wisdom. Unless we have a sense of awe, it seems unlikely that we will escape the modernist idea that everything is put here for us to manipulate.” “Experiencing Deep Time: Brian Swimme On The Story Of The Universe,” The Sun, May, 2001.

[7] Heschel, The Sabbath: Its Meaning for Modern Man. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, NY: 1951.

[8] Rabbi Michael Lerner, Jewish Renewal: A Path to Healing and Transformation, G.P. Putnam’s Sons: New York: NY, 1994.

[9] The Sabbath, 14.

[10] “Resources,” in The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge and Power, Wolfgang Sachs, ed., London: Zed, 1991, 206.

[11] See Simard’s MotherTreeProject.org.

[12] (Footnote 296, 139).

[13] Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries

[14] (33.)