(From a Talk to the Yiddish Culture Club in Los Angeles. Published in Yiddish in Afn Shvel in 2010) Translated by the Author*

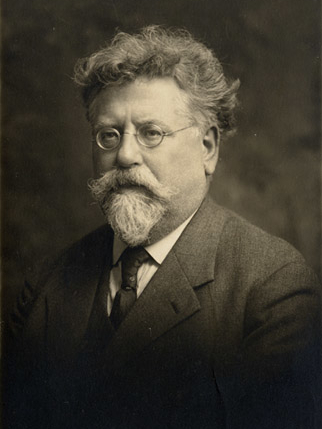

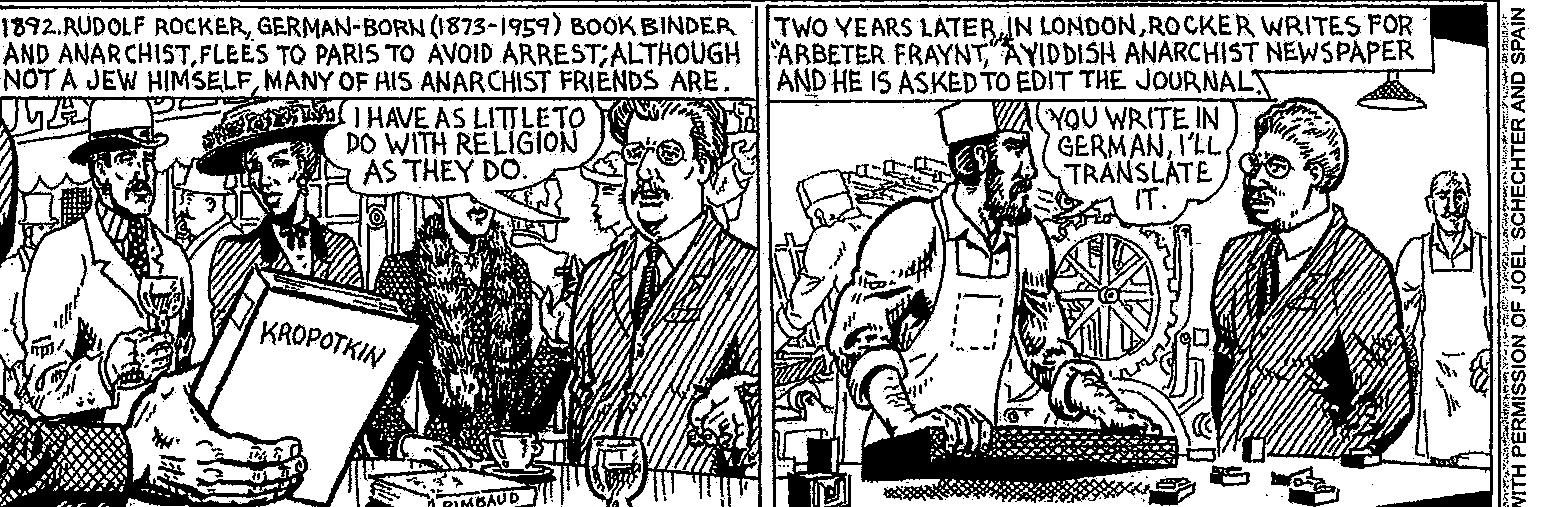

Rudolf Rocker, the beloved leader of the Yiddish Anarchist movement, represents an unusual occurrence in Yiddish language, literature, and political life at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth–in other words, of our recent past.

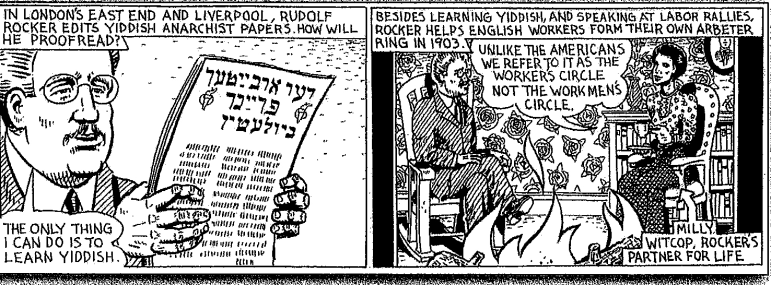

Rocker, a German from the city of Mainz, raised Catholic, taught himself the Yiddish language, and not only wrote in that language and lectured in it, but also became the editor of three Yiddish periodicals–Dos Fraye Vort, Zherminal, and Arbeter Fraynd (The Free Word, Germinal, and Friend of Labor), and was drawn into a certain Yiddish milieu, becoming the beloved leader of a large and significant Yiddish folk-movement. His story and how this happened, what kind of a person he was, is not only interesting, but also, I would say, heartwarming.

Rudolf Rocker was born in Germany in 1873 and died in America in 1958 at the age of 85. All his life, until his death, he was esteemed and beloved as the leader of the “Jewish Free Socialist Movement,” i.e., the Yiddish Anarchist Movement.

His father was a typesetter. When he was 11 years old, both his parents died. For a while, he lived with an aunt, then later, at an orphanage. After a time, he was apprenticed to a bookbinder, and this became his trade.

He was highly intelligent, read a lot, and taught himself world history, literature, and philosophy. For a time, as a young man he wandered through Europe and observed how people lived, worked, and thought in the various European countries and climes. Slowly he was attracted to socialist and Marxist ideas and organizations.

Because of his labor activism, he had to escape from Germany to Paris. There he was invited to a meeting of Yiddish-speaking workers, anarchists; this made such a strong impression on him, that it influenced the rest of his life. Here is how he describes this moment in his autobiography (London, 1922):

Once while I was strolling on the broad Paris boulevards with my friend Liederle on a wonderfully beautiful spring evening in 1893, he suddenly asked me if I would be willing to go with him to a meeting of Jewish anarchists. At first I thought he meant this as a joke, but seeing he was serious, I asked him, astonished, Jewish anarchists? Well then, why not Catholic or Protestant anarchists? No, no, he answered, it is as I tell you–this is not about religious Jews, but about Jews who have as little to do with religion as you and I. In that case, said I, they are no longer Jews, just as we are no longer Christians. He then explained that these are East-European Jews from Russia, Poland, and Rumania who belong to a certain ethnic group that speak a language that is quite similar to German. This aroused my curiosity since I had never heard of such a people.

Rocker did go to the meeting of the Jewish anarchists in Paris and was thus drawn into the Yiddish anarchist world movement.

He tells that two things at that meeting impressed him deeply:

First, the Jews he knew in Germany were either small shopkeepers, or doctors, lawyers, journalists, or engineers, but not workers. Here in Paris, for the first time at this meeting of East-European Jews, he encountered Jews of the working class:

tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, watchmakers, etc.

Second, it affected him greatly that women participated fully in the movement. In the small towns and villages of Germany, women were not prominent, but, he says:

Here in the circle of my new Jewish friends in Paris, things were entirely different. Just as many women as men came to the meetings. The women participated actively in the debates and read the revolutionary literature just as avidly as the men. For me this was a completely new phenomenon. The relations between the sexes were so free and so natural–I had never seen anything like it in Germany.

He was gradually drawn into Yiddish anarchist circles. As he tells it:

As a result, I gradually became close friends with the active Yiddish comrades. I was also a welcome guest in their homes. In this way a whole new world opened up for me, one that was to me totally unknown.

In Paris Rocker also became acquainted with the great folklorist, revolutionary, and, most importantly, dramatist, S. Ansky (Shloyme Rapoport, 1863-1920), the author of the classic Yiddish play, The Dybbuk. For a while Rocker even worked side-by-side with Ansky, who was also by trade a bookbinder. Here is how Rocker describes his friendship with Ansky:

One of the most interesting people I got to know among the revolutionary young people then was S. Rapoport, who became famous in both Yiddish and Russian literature under the pseudonym, S. Ansky….When Rodinson, a comrade, told me that Rapoport was a bookbinder, I took the first opportunity to engage him in a discussion about that trade. During our discussion I told him about the poor and cramped workplace I worked in. He then suggested that I work with him in his place. This plan appealed to me. Just the idea that this arrangement would give me someone to talk to as we worked, tempted me. We quickly agreed. Rapoport then lived in a poor attic dwelling on St. Jacques that was both his living quarters and his workshop. My new friend Rapoport was very talented, but his touching modesty kept him from putting himself forward and occupying the status he deserved. If not for that he would have reached the position in life that he had a right to on the basis of his great intellectual talents. He was then living in the direst poverty, obvious to anyone at a glance, judging from his external appearance. His modesty was boundless, and I am convinced that he quite often subsisted on only tea and bread, never saying a word about it to anyone.

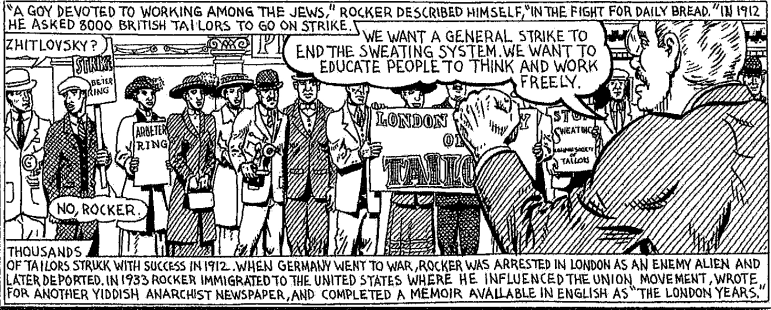

After his visit to Paris, Rocker traveled to England, settling in London. There he saw the poverty and the suffering of the laboring masses, the sweatshops, and the slum dwellings–he also saw the masses of East-European Jews living in the slums of London. Once more he went to the Yiddish anarchist circles, this time in London, and became one of them. He taught himself Yiddish–learning to speak, read, and write. He married (in the anarchist manner, that is to say, without any kind of ceremony, civil or otherwise) a Jewish working girl, a seamstress, Milly Whitekop. He also became acquainted in London with Yiddish writers, as for example, Morris Winchevsky. He lectured on political, historical, and literary topics, and organized and led trade unions for the Yiddish workers in London. The Jewish workers in Whitechapel and in the other poor districts of London grew to love him.

In 1912 Rocker led a great strike of the Jewish workers in London. The strike was successful, and the Jewish workers believed that Rocker’s leadership played an important role in their victory. The following anecdote illustrates how the Jewish working masses grew to love and esteem him:

One day as I was walking with Milly in one of the narrow, squalid streets of the Jewish ghetto, a young woman who was sitting with her children at the door of her house spotted me, and approaching, said to me with obvious pathos, “Please do me a favor, I beg you, wait here for just a moment so that my grandfather can greet you.” I waited, and, after a while, a frail old man with a long white beard who could barely stand on his two feet, emerged from the house. He stretched out his trembling hand to me and said: “May God grant you 100 more years! You helped my children in their direst poverty. You are, it is true, a Gentile, but nevertheless, a mentsh, a mentsh.”

Rocker became renowned not only in Jewish circles. His works were published in all languages, and he became recognized as a thinker and writer worldwide. Along with the Russian Prince Kropotkin and the Italian Malatesta, the Frenchman Proudhon, and the Russian Bakunin, he became known as one of the world’s leaders, activists, thinkers, and writers of the worldwide anarchist movement. World-famous people such as Bertrand Russell, Herbert Reed, Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, and others read him and wrote in praise of him.

Rocker also contributed much to the Yiddish language and literature. He wrote seven books in Yiddish, among them: Sovyetish Sistem oder Diktatur (Soviet System or Dictatorship), Buenos Aires, 1921; Mikhayel Bakunin (Michael Bakunin), Leeds, England, 1902; Di Geshikhte fun der Teroristishe Bavegung in Frankraykh (The History of the Terrorist Movement in France), London , 1906. Eight of Rocker’s books written in German were translated into Yiddish, among them: Zeks Kharakterin in der Velt Literatur (Six Characters in World Literature), New York, 1929. Rocker also translated into Yiddish twelve books of world literature, among them books by Maxim Gorky, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Henrick Ibsen. On the pages of his anarchist periodicals, he also printed translations into Yiddish of these and other great writers, so that Yiddish folk readers would be able to become acquainted with world literature.

* * * *

What were the anarchists after? What did they want? How were they ideologically different from the social-democrats, the Marxists, the historical materialists, and–in the Yiddish world–from the Bundists and communists?

They called themselves “Free Socialists,” but they did not have in mind the same meaning for the word “socialist” as the Marxists. They believed that freedom of people was the highest and most beautiful ideal, and that the Marxists and social-democrats want to force onto humanity another sort of dictatorship, and that even with a parliament and free elections, it is still not in the spirit of freedom. The state and its bureaucracy will become just as dictatorial, even more dictatorial, if socialists come to power than if the bourgeoisie are in power, because the power will be even more concentrated into fewer hands than it is under capitalism. If one wants to live in peace and freedom, one must avoid having one group with power over other individuals.

Anarchy does not mean, in their view, chaos. What it means is that people should live together in freedom, according to how, as members of an equal society, they want to and how they understand things, without the force of a great, all-powerful government. The anarchists would have held that the Israeli-Zionist idea of the kibbutz is an example of what they meant. In a kibbutz people live together, voluntarily, and share their means as equal free people, without some great, powerful government force and bureaucracy.

Anarchists deny that Marx had discovered a kind of “scientific socialism.” Socialism had existed before Marx. Marx and his followers want to establish a kind of theocratic dogma that will further enslave the thinking and opinions of mankind. We, say the anarchists, are socialists without Marx, without dogma and without some great all-powerful state, even a so-called socialist one, that would force upon people whatever it thought suitable–even if that government is a popularly elected one. An elected majority, can, according to the opinion of the anarchists, be just as intolerant as a pure dictatorship. Rocker explains it thus:

My deepest convictions lead me to believe that anarchism cannot be conceived of as a definite, decided, closed system, and also not as a final solution for the coming generations, but instead as a special tendency in societal development that places freedom as a sine qua non in all fields of human activity and thought; and for that very reason, anarchism cannot be established as a rigid, unchanging directive or line. Freedom is never entirely achieved but is always that toward which we must strive. Every generation is faced with its own task which cannot be determined in advance. The worst kind of despotism is the tyranny of inherited, accepted ideas which are no longer capable of any further inner development and are predetermined to explain everything according to an established norm.

* * *

In 1897 Rocker and his anarchist, Yiddish wife, Milly, traveled to America. Their attempt to enter the country was reported in every New York newspaper. They were not, however, allowed to enter the United States. The reason is interesting, typical, and reveals the character of Rocker and his wife as well as the anarchist view of things. They were not allowed to enter because they never married, and they were determined not to get officially married, even if it meant they could then enter the United States. Here is how Rocker describes the official investigative hearing of him and his wife:

One of the officials turned to me and said in German: “You maintain that you have forgotten your marriage certificate, but one doesn’t forget such an important document when one travels on such an important trip.”

“There was absolutely no such claim,” I said calmly. “I simply said that we don’t have such papers because we never tried to obtain them. Our bond is the result of an agreement freely made between my wife and me. That is a strictly private matter, and we alone bear the responsibility for it, without any need for any legal certification.”

Rocker and his wife would in no way give in. The officials suggested that they get married, and they would be then permitted to enter. Rocker and Milly rejected such a suggestion. Rather than be married officially they were prepared to return to England. And that is, in fact, what happened. They returned to England and lived together for many years as husband and wife, always faithful and devoted to each other. In 1933 they were finally permitted to enter America. Milly died in New York in 1955.

* * * *

Even more interesting to me than his ideas or his anarchist ideology is Rocker’s character, his personality. Often in radical movements one can encounter a person whose social or societal opinions are beautiful, humane, but that person himself in his personal life and in his relations to others is not humane or sympathetic. Rocker, however, was luminous, warm, and tolerant, the embodiment of his own ideals. Everyone respected him and grew to love him, even his political opponents–and not because he concealed his opinions, but quite the opposite, he steadfastly and courageously expressed them.

A good example of this is his difference of opinion with Kropotkin, his good friend and anarchist comrade who was living in England at the same time he was. Rocker regarded Kropotkin as his teacher, guide, and close friend. But when the First World War was threatening to break out, Rocker came out against the war, even though his close anarchist comrade spoke and wrote in favor of the war. Because he was classified as an “enemy alien,” Rocker was imprisoned for four years. But despite their difference of opinion about the impending war, Kropotkin and Rocker maintained their friendship, remaining true to each other. Kropotkin worked ceaselessly to free his old friend and his wife Milly from their English prison. Rocker, from his side, always respected and held dear his old friend, Kropotkin.

In order to fully understand what character, principle, consistency, and courage mean, one only has to see how Rocker conducted himself in prison, with its dreadful and inhumane conditions. As an elected representative of the prisoners, he demanded better conditions for them. He gave lectures about literature to the prisoners. In prison, he was consistently honest, courageous, and devoted to his fellow human beings.

After the First World War, Rocker returned to Germany and continued organizing, speaking, and writing among the German workers. At the same time, he also submitted articles to the Yiddish anarchist periodicals, e.g., Di Fraye Arbeter Shtime in New York.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, Rocker and his wife escaped to America. This time they let them in. He abandoned everything in Germany: his papers and his library of over 5000 books. The barbaric Hitlerites burned them all.

Until his death in 1958 Rocker lived, wrote, and worked in America.

* * *

One might ask, what does all this have to do with us today? In other words: It is singular, interesting, historical, scholarly, but what does anarchism and Rudolf Rocker have to do with us?

In our time, as in all times, humanity seeks an answer to the question of how to reorganize society so that all will be able to eat to satiety and live in dignity and in peace. The anarchist ideas have much to teach us about these issues. They remind us, for example, that when power is concentrated in too few hands it will lead to bad results.

I will give Rocker the last word on the relevance of anarchistic ideas:

Well, I hope that my book will present the next generation, the youth, with specifics from which it can learn. For the older generation, who themselves lived through those beautiful days of battle, of a time gone by, and yes, fought in them, may my book allow them to relive their youth. To them I send my brotherly greetings over shore and sea, and I feel myself closely bound with them as in the days of our great longing and yearning for the golden dreams of our youth. May they always remember that nothing that one does for the great ideal of social justice, humaneness, and for the liberation of all peoples is ever lost.

* * *

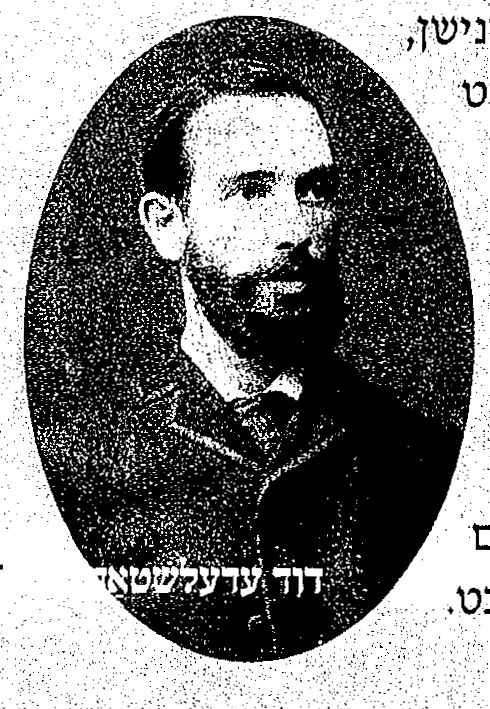

It is almost impossible to speak about the Yiddish anarchist movement without speaking about the great Yiddish labor poet, Dovid Edelshtat. Rocker says the following about him:

If his poems were able to influence strongly the Yiddish workers of all lands, it is no accident. In his songs he struck a note that streamed from the depths of his heart, and they therefore had to find an echo in the hearts of the poor, downtrodden people. He not only sang of their dismal fate, but shared it, feeling it on his own flesh, living through and experiencing it himself.

His poem Mayn Tsevue (My Last Will and Testament), was set to music and became the hymn of the Yiddish anarchist movement:

My Last Testament

by

Dovid Edelshtat

(A free verse translation of a poem that is rhymed and

metrical in the original Yiddish. Translated by Marvin Zuckerman)

O Dear Friend! When I die,

Carry to my grave our flag–

The free flag, with its red colors,

Sprinkled with the blood of the workingman.

And there, under that red flag

Sing my song, my freedom-song!

My free song, my battle song,

For the enslaved Christian and Jew.

Even in my grave, I will hear it,

My free song, my battle-song.

Even there I will shed tears,

For the enslaved Christian and Jew.

And when I hear the swords ringing

In the last battle of blood and pain,

I will, even from my grave, sing to the people,

And uplift its heart.

* * *

Note: Of course, as you undoubtedly have gathered, the Yiddish anarchists were not assassinating, bomb-throwing anarchists, but rather, philosophical anarchists

FOOTNOTE:

*All quotations of Rudolf Rocker’s words are from I. Birnbaum’s 1922 Yiddish translation from the German of his autobiography, In Sturm.