The title of this very compelling film, now in theaters and streaming on Netflix, gives the viewer a hint of what is to come. The film, put together by Scorsese, is actually a fusion of fiction and footage from Bob Dylan’s 1975-77 tour and is a story rather than a true documentary. It opens with a scene from George Melies 1896 silent film about magic, The Vanishing Lady, and is a clue that there might be some sleight of hand to follow. It is, like Dylan himself, mischievous in its retelling of the creation and performances of the legendary Dylan tour that happened just as America was recovering from the ravages of Vietnam, the corruption of Watergate, and the selling of the Bicentennial of American independence.

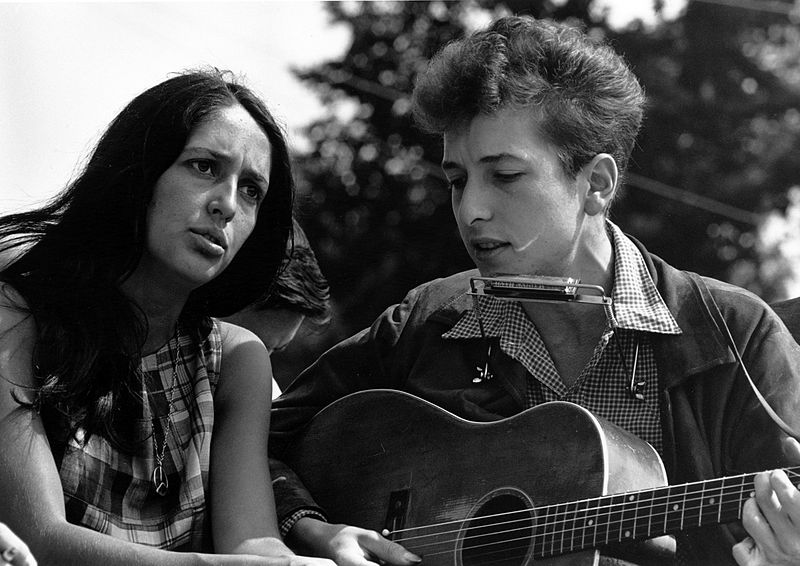

The Rolling Thunder Revue was never deemed a success, “not if you measure success,” says Dylan, “in terms of profit.” It wasn’t profitable because Dylan, just emerging from a period of isolation following his motorcycle accident, wanted to play to small towns and small venues across the county, resisting corporate pressures to play to stadiums. For Dylan, it was a success because “it was a sense of adventure.” He drove the band’s bus himself. He played for people who wouldn’t ordinarily go to rock concerts, in forgotten towns hit by economic depression, in a prison and an Indian reservation. The tickets were inexpensive at $8.50 each. Dylan performed with a caravan of an astonishing group of musicians, poets, singers, among them Allen Ginsberg, Joan Baez, the amazing violinist Scarlett Rivera, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Patti Smith, Joni Mitchell—and they allowed each other to play and perform in ways that the corporate promoters would have never tolerated. They joyfully engaged with each other and with their audiences. Dylan is loose, playful in his wide brimmed hat adorned with flowers, feathers and butterflies, and often in whiteface or a mask. He smiles a lot, something we don’t often see, and sings his songs with passion and pleasure and clarity. The music alone is phenomenal—you really GET the power and beauty of “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”, the prophetic “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall”, and the chilling rendition of “Hurricane”, the ballad of the falsely accused and imprisoned boxer, Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. You hear each word, and the musicians and singers are in exquisite harmony and synchrony. And there are beautiful moments captured behind the scenes, of Dylan and Ginsberg at the grave site of Jack Kerouac, of Dylan and Baez reminiscing about their relationship.

And the sleight of hand? When asked about the use of white face and masks in the review, Dylan tells us that a person “who’s wearing a mask, he’s gonna tell you the truth. When he’s not wearing a mask, it’s highly unlikely.” The question of what is truth and what is fiction plays throughout this film. It plays with our sense of reality and time by interspersing archival footage of the tour with contemporary interviews—what is memory and what is truth, what is real and what is not? The now 78 year old Dylan, looking like an aging rebbe, tells us that the naming of the revue came when he actually heard thunder, and someone told him that “rolling thunder” means “speaking truth” for Native Americans—truth or not? The original footage from the revue is presented as the work of European filmmaker, Stefan Van Dorp, who in contemporary interviews appears to be an effete and snobbish aesthete—he turns out to be a total fiction, played beautifully by Bette Midler’s husband, Martin von Haselberg. The actual and original footage was taken by the Chicago cameraman, Howard Alk. A further fiction that might slip by is the interview with Congressman Jack Tanner, who says he got to see the performance because Jimmy Carter, a real Dylan fan, called Dylan. Jack Tanner, however, is played by Michael Murphy, who played the same character in Robert Altman’s film satirizing politics, “Tanner 88”.

These fictions add a Zelig like playfulness to the film, but they never take away from what is most important—the music, the lyrics, and the consciousness of the performers. At the end of the film, Allen Ginsberg says about Rolling Thunder:

“You who saw it all, or saw flashes and fragments, take from us some example, try and get yourselves together, clean up your act, find your community, pick up on some kind of redemption of your own consciousness, become more mindful of your own friends, your own work, your own meditation, your own proper art, your own beauty. Go out and make it for your own eternity.”

We need a Rolling Thunder Revue today. Until that transpires, this film will thrill and inspire both oldies who remember, and today’s youth who will appreciate the power of taking transformative music on the road.