Memoirs tend to center the notion that tragedies and setbacks can be, indeed need to be, overcome. Readers expect to be inspired by the author’s story, and maybe learn how they, too, might get past disappointment, pain, loss, and suffering.

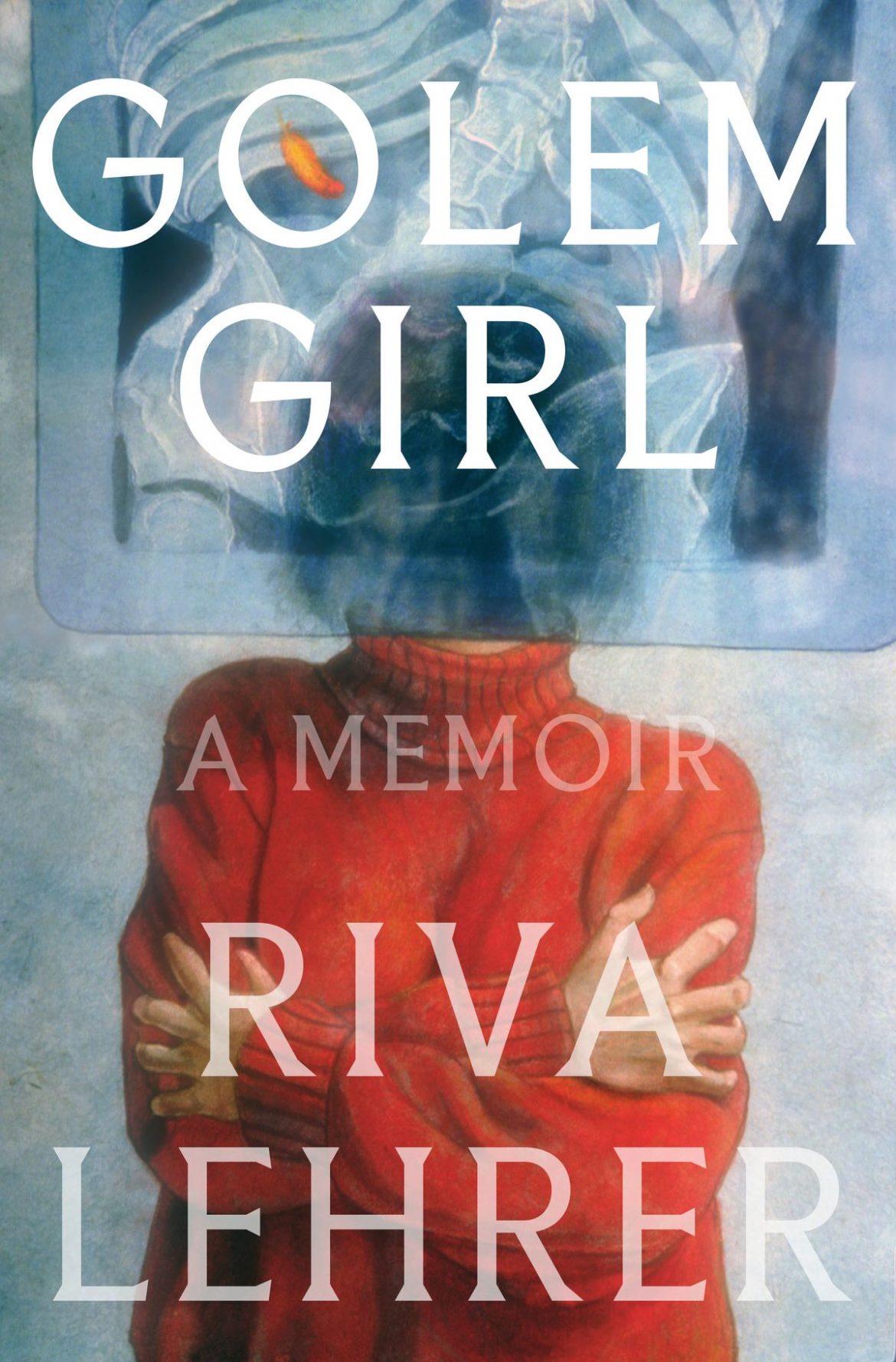

“Golem Girl” breaks that mold. Written by artist Riva Lehrer, who lives her life with spina bifida, it exposes the genre’s typical positivism as a veiled form of pity that says, “Fear not, with the right attitude your objectionable reality can be altered!”

Lehrer, in fact, shows how the very idea of normality is an illusion. As an instructor in the Medical Humanities Departments of Northwestern University—one of many professional roles she fills—Lehrer leads future medical professionals in drawing exercises in which they sketch preserved human fetuses showing a range of genetic anomalies. Students may enter the class clinging to the infantile programming that taught them to see these fetuses as deformed or abnormal, but over time they begin to see them as beautiful representatives of the true diversity of possible human experiences.

This is just one example of how Lehrer has devoted her life to the goal of cultivating empathy. Sympathy and pity, she explains, require othering by positioning us outside of each other’s realities. Empathy asks us to actually feel what it is to be someone else.

Born in 1958, Lehrer lived the first two years of her life in the hospital, enduring multiple surgeries. Back then, in the rare instances when a child with spina bifida did not die at birth or soon after, doctors were trained to lead parents to believe the child could have no reasonable expectation of a productive, happy life. Most children with Lehrer’s prognosis lived in institutions, rarely seeing their families again.

Lehrer’s mother fought with doctors and administrators for the right to take her daughter home, regardless of what complications the system warned her that would entail. Lehrer speculates that her mother’s devotion had something to do with the two babies she previously lost in childbirth. This, Lehrer says, was a type of “dark luck”—a tragedy that nonetheless helped ensure her survival.

Reading the phrase “dark luck,” I first wondered, isn’t it always necessary for someone to fail so that someone else can succeed? Then I thought about how many people must see someone with a genetic variation such as Lehrer’s and think her survival was not lucky at all, since she has had to endure so much pain, disenfranchisement, and othering from abled society.

I now find Lehrer’s concept of “dark luck” revelatory of how luck only exists inside of social constructs based on the belief in opposites, such as winners and losers. Within a social construct that values all experiential variations equally, the concept of luck would not exist.

It is precisely because we live in a culture obsessed with concepts such as luck and opposites that Lehrer calls herself a monster. That’s what a golem is: a clay monster in Jewish folklore brought to life by supernatural powers.

“Golem Girl” candidly, and frequently poetically, elucidates how a golem can be both predator and prey. Monster and master are just different terms for outsider and insider. Crucially, Lehrer shows us how golems become scapegoats—blamed whenever it serves the master’s purposes.

Like all golems, Lehrer has faced a never-ending barrage of expectations to perform to whatever role the masters give her, whether it’s the timeless expectation that she adapt to failed, i.e. handicapped inaccessible, architecture, or the recent demand that she accommodate society’s claim of freedom to go mask-less.

Her memoir offers a reasonable alternative to the monster/master dichotomy by revealing variation as the default condition of nature, and empathy as the prerequisite for human sustainability. Nowhere is the way forward more clear than in Lehrer’s portraiture practice, which is detailed at the end of the book. Grounded in collaboration between artist and sitter, her studio practice is itself an act of exploring the idea that when we empathize with each other, we become harbingers of a culture not based on the fiction of opposites, but on the fact that our destinies are intertwined.