Review of Ellen Bernstein’s THE PROMISE OF THE LAND: A PASSOVER HAGGADAH (Behrman House 2020) by Rabbi Jonathan Seidel, PhD

In an era when a plethora of haggadot are being published for diverse audiences, Rabbi Ellen Bernstein has given us a marvelous new contribution in an ecological vein. The Promise of the Land follows her earlier significant and pioneering work in Judaism and ecology. For me, this project is quite personal since Rabbi Bernstein was one of my earliest inspirations for ecological Jewish study and action, and I share with her a love of Aldo Leopold, the father of American eco-philosophy—whose idea of a land ethic informs this haggadah. I was introduced to Leopold at roughly the same time that my forester father Herb, Alav HaShalom, gifted me a copy of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. In the 1940’s, before “environmental studies” majors even existed, my father attended Forestry school at the State University of New York, where he absorbed Leopold’s message. He and his classmates learned to practice a kind of sustainable forestry from Leopold’s framework.

The Promise of the Land is a work of creative liturgy. As such it takes its place among other path-breaking interpretations of liturgy. In 1969 Rabbi Arthur Waskow had revolutionized our approach to the Passover liturgy by reimagining the Passover Seder as the Freedom Seder. Before that, there had been Zionist Seders that emphasized peoplehood and nationhood, as well as many other progressive Seders. I grew up with a Yiddish socialist Arbeiter Ring Seder. In the late 80’s, Bernstein published the first ecologically rooted Jewish liturgy, the Tu B’Shevat Seder, The Trees’ Birthday: A Celebration of Nature, which served as a locus of liturgical kabbalistic-environmental activity for many years, and elevated the status of the often dismissed holiday (Tu B’Shevat Matters).

It would take several decades, however, for a true ecologically oriented Passover haggadah to emerge.

Bernstein’s Promise is not the first ecologically sensitive haggadah that I am aware of. I would be remiss if I did not note the excellent and comprehensive Seder and commentary, Haggadah of Heaven and Earth by Krista Hyde of Washington University (2010), which invokes a variety of teachers of eco-kashrut and earth justice. This outstanding 184-page haggadah is more of a reference work than a usable liturgical guide for Pesach. It is available at https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1470&context=etd

The Promise of the Land is also a work of eco-philosophy. Bernstein’s primary challenge in creating an ecologically oriented haggadah was to connect freedom—the central idea of the haggadah—to the earth. She has done this quite successfully. By reclaiming two land-centered verses from the original instructions for Passover that had been abandoned for millennia, and reading them ecologically, Bernstein has sparked a radical way of considering the meaning of the Hebrew “aretz”. In the introduction to her haggadah (and other articles on her website www.thepromiseoftheland.com), she discusses how aretz, which can mean both land and earth, must be understood as a living organism, not as flat, inert stuff, not as territory or real estate, nor as the land of Israel solely.

To my mind, this is a simple but brilliant move. This bold step in re-translation and rethinking allows us to look at earth and land from the prism of balance, reciprocal relationships, and care.

With dexterity, Bernstein shifts from the “giftedness” of the Genesis covenant and a unilateral promise, to an emphasis on ecological and ethical responsibility, and the hope that once we humans understand the necessity of our role, we will guard the land, exercise stewardship, and (as a corollary) reduce our carbon footprint. While our ancestors did not have to spell it out, we do, and Bernstein does this creatively and with accurate, elegant translations.

The Seder Bernstein envisions does not thrust us headfirst into the climate emergency. It is not a “Climate Emergency” or “Scorching Earth” Seder. Rather it reminds us to free ourselves from the internal Pharaoh of overconsumption and once we have liberated ourselves from that enslavement we can move into guardianship of the land, as imagined in Leopold’s Sand County Almanac.

Throughout the haggadah, Bernstein offers pungent and highly-selective texts that encourage us to care for creation. She also offers poignant, deep ecological gems along the way. This is from Joseph Ibn Kaspi:

“In our pride we foolishly imagine that there is no kinship between us and the rest of the animal world, how much less with plants and minerals…the Torah inculcates in us a sense of our modesty and lowliness, so that we should be ever cognizant that we are of the same stuff as the ass and the mule, the cabbage and the pomegranate, and even. . . the stone.”

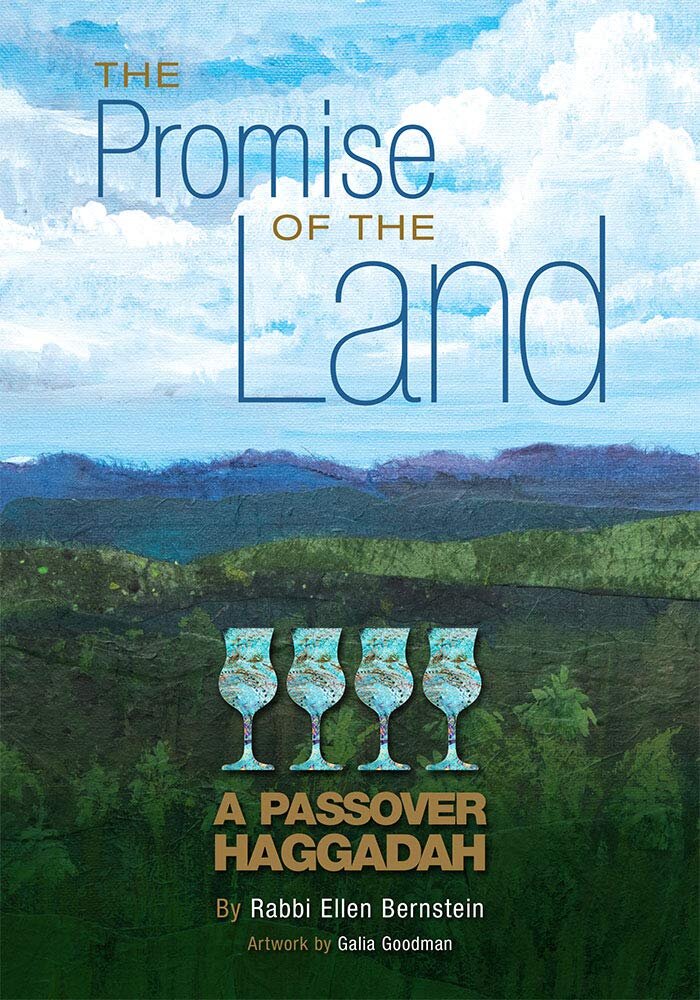

Another virtue of Bernstein’s Promise is that it serves as a beautiful example of “Hiddur Mitzvah”—adorning a commandment. It is gorgeously illustrated by Galia Goodman whose work lifts up the haggadah by offering a visual midrash. Further enhancing its artistry, the haggadah is color-coded and user-friendly, not burdensome, with traditional text and new commentary that manages to be both brief and stimulating. Bernstein integrates natural scientific explanations of miracles without subtracting from the mythopoetic impact of the story. Her work is midrashic in the best sense, of seeking to extract or should I say divine the meaning of the Seder for our times.

It is a haggadah in the spirit of Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Promise, the haggadah, offers thoughtful earthy commentary on familiar rituals. Here is one example:

“The Hillel sandwich combines three essential food types: wheat, a grass that sprouts from the earth, horseradish, a root that is buried deep underground; and apples (charoset) a fruit that hangs from a tree.” Perhaps we might have benefited from more water-awareness and the mitzvah of protecting and healing our oceans, rivers, streams and riparian biomes.”

Bernstein also offers pithy yet powerful comments and provocative questions about our values. This Seder brings some delightful and surprising new translations of traditional liturgical poems, such as Ehad MiYodea, as well as an eco-aware super-commentary (like Tosafot on Rashi on Gemara). The glosses serve as provocative apothegms for our time— perhaps even prophetic. I was also inspired by the move beyond the inclination towards “othering” found in the traditional haggadah. To quote Rabbi Benjamin Weiner, who contributed the following drash to the haggadah:

“The traditional Haggadah draws a sharp distinction between oppressor and oppressed – the Egyptian overlord and the Israelite slave. While our world is plagued by such stark imbalances of power, I find myself pre-occupied with the way that our society locks us, its beneficiaries into oppressive roles. My daily routine is sustained by the ceaseless extraction and burning of fossil fuels. When I try to take stock of this, I want to cry out to God, not as an enslaved Israelite but as an Egyptian, sickened by the destructive power entangled in my hands. Going back to the Land – learning to grow a large portion of my family’s food with regenerative techniques, drawing sustenance from the parcel of earth where we make our home while also doing my best to restore it as habitat to birds and bees, bears and butterflies – has felt, in this regard, like liberation.”

The Pharaohs of our age are cancelling environmental protection laws in the U.S. and Brazil, and corporate money is corrupting scientific work and its dissemination; ours is a time of blindness and short sightedness. Today’s oligarchs value profit and extraction of resources over human and other-than-human life, over our Gaian Mother, just as Pharaoh valued the construction of the Pyramids over peoples’ lives, and the builders of the Tower of Babel valued bricks over peoples’ lives. I suggest we consider the struggle to overcome the contemporary Pharaohs and their privileging of profits as a two-fold process: One a gezerah of “Horaat Sha’ah” an emergency decree that mandates action. And two—a spiritual shift, one that has been midwifed in the pages of Tikkun Magazine: a new consciousness that will ignite the first radical change. “Nishmah V’Na’aseh”— Understand, then act. We must act against the external Pharaoh and the internal one as well.

Pesach as we know, revisits the foundational myth of our people, moving through the labor pains of Egypt and the birth canal of the Sea. Now we must revisit Pesach in relation to conscious landedness, the reimagining not of a return to Eden, but a movement forward into the balanced ecosystem of all of Earth’s biomes and topographies that allows for human and other-than-human survival.

The Promise of the Land is a Seder for all Jews and friends and carries a critical and essential message for our time, echoing our Shmita-conscious ancestors: It is incumbent upon us to work to fulfill the promise of the land, in loving cooperation with our Creator. It is perhaps the most potent and timely re-imagining of the Pesach message in the last few years. Here Rabbi Ellen Bernstein has made her mark. This literary work of art joins that of scholars and artists who are producing excellent new liturgies and eco-philosophies throughout North America, Europe, and Israel. In The Promise of the Land, we have the perfect blueprint for a truly integrated, holistic, and practical Seder.