“We die, that may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.” (Toni Morrison from her Nobel Lecture.)

I was on the twenty side of twenty-something, a stay at home mom with an infant and time to read. I had already read The Bluest Eye and Sula, two of Toni Morrison’s early novels, when I saw a television interview where she explained why she started writing novels. She said she realized that she would have to write the novels that she wanted to read. This, for me, was a eureka moment. It was an epiphany. The clouds parted, the sun shone through, a heavenly choir sang; Hallelujah. Amen and Ashe.

This moment was more than a writer explaining her own life, it was more than permission for a reader to leave her work wanting something more, but it was a challenge, a charge, a command. I knew that at some point I would have to not only write the novels and short stories that I wanted to read, but I would have to do more than that. I would have to write the analysis of current events and of history that I wanted to read. If something needed to be said that I did not know had already been said, I would have to say it.

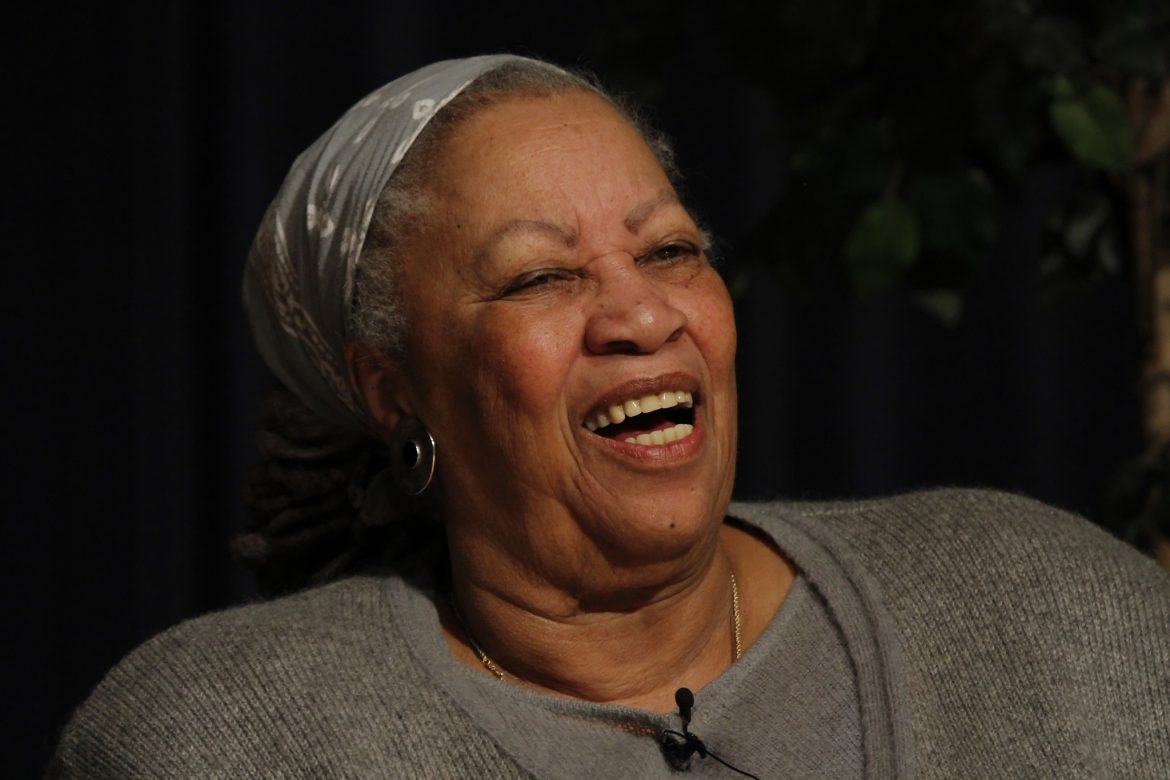

Toni Morrison, Nobel Prize winning author died on August 5th, but she leaves behind a body of work from her own mind that will last for centuries. Beyond that, her legacy includes those of us who she inspired to claim our own voices and to write what we want to read. Hallelujah. Amen and Ashe.

While I appreciated Toni Morrison’s work, I am not a big fan of magical realism, a style of literature that describes some of Morrison’s work. I live my life in a world of magical realism. I feel the presence of the ancestors, and I am surrounded by an invisible praetorian guard composed of the spirits of the dead from the East St. Louis pogrom of 1917. I grew up in the neighborhood where they died. I planted flowers in the dirt that absorbed their blood all those years ago. As a girl, I climbed the tree in my backyard that grew from that hallowed ground. I did not know it then, but I know it now. There is something that keeps pulling me and drawing me on as both the Pattersonaires and Sweet Honey in the Rock sing. It is God the Mother, God Black Jesus, God the Holy Ghost.

Yet, I recognize the people and the names and the food and the gardens in Toni Morrison’s fiction. As James Weldon Johnson observes in his 1921 “Preface to the Book of American Negro Poetry”: “The fact is, nothing great or enduring in music has ever sprung full-fledged from the brain of any master; the best he gives the world he gathers from the hearts of the people, and runs it through the alembic of his genius.” I say: this is true for writers as well.

Johnson, in writing about the move of Africananist poets, including African-American poets away from writing in dialect, he says that such poets need “a form that is freer and larger than dialect, but which will still hold the racial flavor; a form expressing the imagery, the idioms, the peculiar turns of thought, and the distinctive humor and pathos, too, of the Negro, but which will also be capable of voicing the deepest and highest emotions and aspirations, and allow of the widest range of subject and the widest scope of treatment.” Toni Morrison’s language advances this project.

Her imagination, expressed through her language, creates another world to live in that also re-creates those who were willing to allow the language to work its transformative power. When Baby Suggs preaches her sermon in the novel Beloved she echoes the same sense of self- love that my Sunday School teachers taught when they told me that I was a child of the King, and I believed them. Baby Suggs said:

“”Here,” she said, “in this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard. Yonder they do not love your flesh. They despise it. They don’t love our eyes; they’d just as soon pick em out. No more do they love the skin on your back. Yonder they flay it. And O my people they do not love our hands. Those they only use, tie, bind, chop off and leave empty. Love your hands! Love them. Raise them up and kiss them. Touch others with them, pat them together, stroke them on your face ‘cause they don’t love that either. You got to love it. This is flesh I’m talking about here. Flesh that needs to be loved. Feet that need to rest and to dance; backs that need support; shoulders that need arms, strong arms I’m telling you. And O my people, out yonder, hear me, they do not love your neck unnoosed and straight. So love your neck; put a hand on it, grace it, stroke it and hold it up. And all your inside parts that they’d just as soon slop for hogs, you got to love them. The dark, dark liver—love it, love it, and the beat and beating heart, love that too. More than eyes or feet. More than lungs that have yet to draw free air. More than your life-holding womb and your life-giving private parts, hear me now, love your heart. For this is the prize.”

And, I say that this love is necessary to love God with all our hearts and souls and minds and our neighbors as ourselves. Morrison called and calls us still to add our voices to hers. A complementarity. Hallelujah. Amen and Ashe.

Time passed. I was working on my Ph.D. when the Clarence Thomas Hearings began to confirm Thomas to replace Justice Thurgood Marshall on the Supreme Court. I was interested in the hearings before the Anita Hill portion because I was interested in the push and pull between progressive and conservative thought in African-American history, and I was also interested in the clash of interpretations regarding Thomas. When Anita Hill’s allegations of sexual harassment in the workplace came to light, the hearings exploded into an entirely different space.

I confess, I did not understood Anita Hill at first. She was unlike the women who were my role models. They were beautiful women who would have put Thomas in his place in a nanosecond. They were beautiful women who would fight a man, quit a man, quit a job or yes him into submission. Yes maybe. Yes if. Yes when. I must be one of the few women in the United States of America without a #MeToo story. I did not understand why a woman holding a law degree from Yale would work in an uncomfortable situation. Freedom from such nonsense is a reason one gets a law degree from Yale. It was not until I started reading womanist and feminist texts that I started to understand what happened to Anita Hill.

In her introduction to the collection of essays – Race-ing Justice, En-gendering Power: Essays on Anita Hill, Clarence Thomas, and the Construction of Social Reality – Morrison read Thomas through the lens of the character Friday in the Daniel Defoe novel Robinson Crusoe. For Morrison, Thomas was like Friday in that he is a recipient of the life-saving grace of Crusoe and willingly becomes his servant. He becomes a servant who gives up his own language, his own culture. He not only speaks the master’s language and does the master’s bidding, but he thinks the master’s thoughts.

When I wrote about Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill, I read them through the lens of Zora Neale Hurston’s essay “The ‘Pet Negro’ System.” Published in 1943, Hurston defines the pet Negro as “someone whom a particular white person or persons wants to have and to do all the things forbidden to other Negroes. “ It is a system beneficial to both whites and blacks because the black person can rely on his white friends for help when needed. Sometimes these relationships leads to friendships that Hurston says do not make sense. “It just makes beauty.”

More time passed, and in 1995, Toni Morrison spoke before the American Academy of Religion meeting in Philadelphia. She read from her novel Paradise that at that moment was a work in progress. We womanist scholars sat in our own Amen corner and waved our hands at her, missing our white handkerchiefs, throwing her our invisible blessings and affirmations. We would go on to write the books and essays and sermons and poems and prophecies that we wanted to read. We would write the syllabi to the classes we wanted to teach. I taught Paradise when I taught a class on Womanist/Feminist Ethics. It is a story of women who leave difficult circumstances to form a community of their own on the outskirts of an all-black town. Morrison describes the woman without regard to race. The women are a threat to the men in the town who scatter their marginal community with violence. However, they represented a hope that left people asking: “When will they reappear, with blazing eyes, war paint and huge hands to rip up and stomp down the prison calling itself a town.”

Toni Morrison’s language helped us to see beyond sight. And she challenged and commanded us to write our own vision of a better world. If we can write the vision, we can live the vision. Thank you Toni Morrison. We hope to make you proud by writing the books we want to read. Hallelujah. Amen and Ashe.