There are times within the past, present, and future of now when history demands that we pause and consider the past. There are times when memory is more than a nostalgic walk down memory lane to make ourselves feel good. There are times when we have to face an ugly, awful, brutal, barbaric past to understand just how far the moral evolution of humanity has progressed, and, at the same time, to see just how far humankind has still to go.

This year is the centennial of the Red Summer of 1919. James Weldon Johnson, author, journalist, diplomat, the man who wrote the words to Lift Every Voice and Sing, the song known as the Negro national anthem, and starting in 1916 Field Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), named that summer the Red Summer because of the blood that stained the earth and the streets of the United States. African Americans have faced physical and psychic violence, torture and terrorism since the arrival of the first enslaved person on these shores. The Middle Passage, the journey for the enslaved from Africa to the Americas was a horror beyond words. The Red Summer, however, was different in terms of the number of attacks upon whole communities that occurred in such a short space of time.

At the birth of the United State of America, white men who did not own property could not vote. However, in the 1830s, during the administration of Andrew Jackson, the franchise expanded to include most white men over 21. It was at this moment when “white” became a qualification to vote that white supremacy became even more toxic to the body politic.

In the documentary Africans in America: America’s Journey Through Slavery historian Nell Irvin Painter describes the Jacksonian era as one for the common man as long as the common man was white. Personhood, citizenship were reserved for white men. She says:

“This is, I would say, the great watershed where whiteness makes the big difference in becoming a citizen.”

Historian Noel Ignatiev makes a similar observation in the same documentary:

“The racial system, the system of white preferment in employment, in political access, and in citizenship came to embrace virtually all so-called white people in this country who did in fact have a stake in the advantages of racial supremacy. They had access to jobs from which even free Negroes were excluded. They had the right to vote. So, definitely white people gained from the system of racial supremacy. Without that, white itself would have been a meaningless category. It would have simply been a physical description like tall.”

After the Civil War, after Reconstruction, African Americans hoped upon hope that their lives in the United States would be better. They hoped for freedom and equality. However, the racism and white supremacy that justified slavery in a nation built upon the principle that all men were created equal kept its death grip upon the psyche of many white Americans. In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington to dine at the White House, and the outrage was public and unequivocal. In his book The Progressive Era and Race Reaction and Reform, 1900-1917, David W. Southern describes the response:

“Although the presidential gesture pleased African Americans immensely, it set off an orgy of alarm in the South, indicating the mounting racial hysteria of the region. The Memphis Scimitar called Roosevelt’s action ‘the most damnable outrage ever perpetrated by any citizen of the United States.’ On the Senate floor, ‘Pitchfork’ Ben Tillman shouted, ‘[E]ntertaining that nigger will necessitate our killing a thousand niggers in the South before they will learn their place.’”

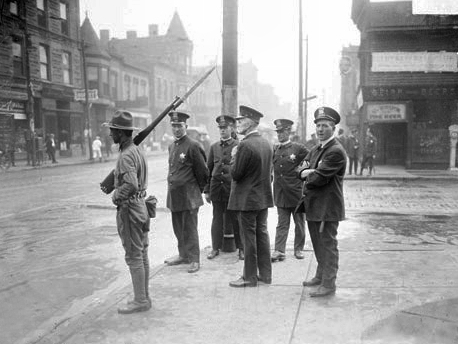

The violence of the various pogroms and race wars that happened in the early years of the 20th century, North and South, was a method by which to keep African Americans in their place. As black people moved North to work in various industries and to escape the violence of Jim Crow, American apartheid (apart hate), white people saw their presence as competition for jobs and their nascent political power as a threat.

Then came World War I. African-American men joined the army. W.E.B. Du Bois urged African Americans to “Close Ranks.” He wrote: “Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy. We make no ordinary sacrifice, but we make it gladly and willingly with our eyes lifted to the hills.”

African Americans fought in the war. Some earned the Croix the Guerre, a medal of honor given by the French for courage and for gallantry. Du Bois and others thought that African-American veterans would come home to a country grateful for their service, a country that would now give them the freedoms that come with democracy for which they had fought on European soil. Sadly, this was not the case. To enforce white supremacy, white mobs from East to West attacked individual black veterans, and, on one pretense or the other, attacked black communities. Du Bois describes the events in his book Dusk of Dawn.

“The year 1919 was for the American Negro one of extraordinary and unexpected reaction. This reaction had two main causes: first, the competition of emigrating Negro workers, pouring into Northern industry out of the South and leaving the Southern plantations with a shortage of their customary cheap labor. The other cause was the resentment of American soldiers, especially those from the South, at the recognition and kudos which Negroes received in the World War; and particularly their treatment in France. In the last case, the sex motive, the brutal sadism into which race hate always falls, was all too evident. The fact concerning the year 1919 are almost unbelievable as one looks back upon them today. During that year seventy-seven Negroes were lynched, of whom one was a woman and eleven were soldiers; of these, fourteen were publicly burned, eleven of them being burned alive.

“That year there were race riots large and small in twenty-six American cities including thirty-eight killed in a Chicago riot of August; from twenty-five to fifty in Phillips County, Arkansas; and six killed in Washington. For a day, the city of Washington in July, 1919 was actually in the hands of a black mob fighting against the aggression of the whites with hand grenades.”

Many of the riots, pogroms, became race war as African American veterans organized other men in the community for self-defense. The idea of the New Negro, an African American who would not meekly accept second-class citizenship, had been around for some time before 1919, but the concept acquired a fresh meaning as African Americans literally fought for their safety, dignity and later for justice in the courts.

For more on the Washington DC riot see: https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/07/15/deadly-race-riot-aided-abetted-by-washington-post-century-ago/?utm_term=.8ef54519a508.