[Editor’s introduction: Here are some of the ways Tikkun authors have reflected in the past on the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. — an essay by professor of African American studies Obery Hendricks and an essay by Ariel Dorfman. I was at MLK Jr.’s speech in D.C. in the summer of 1963 and that March on Washington changed my life. I then had the honor of meeting personally with MLK Jr. in 1968, a month before he was murdered, as a representative of the Peace and Freedom Party. I tried to convince him to run for President that year.

The best way to honor MLK Jr. is to BE MLK Jr. by becoming an embodiment of his activism, his vision, and his commitment to a world of love and justice. It isn’t easy to do in the 2019, but it wasn’t easy to do for King either. Learning to be a spiritual progressive like King is not just studying his example but then trying to apply his message by making it our own, and then, like him, nuancing both strategy and tactics to the realities we face today, always aware that our task is not to accommodate to reality, but to change it. For many, it helps to have a spiritual practice to strengthen us. — Rabbi Michael Lerner, Editor, Tikkun]

***

Meeting MLK Jr. Again for the First Time

By Obery Hendricks

I first met Martin Luther King at the age of seven at Bob’s Barber Shop (“Baba Shop” we pronounced it) on a once busy avenue in East Orange, NJ, a few blocks from the Newark line. The federal government’s voracious Urban Renewal (read: “Negro Removal”) Program has long since reduced Bob’s and everything around it to rubble, but what I heard and learned there throughout my youth informs and enriches me still.

Like so many black folks’ barbershops, Bob’s was much more than a place for a shave and a haircut. It was a welcoming epicenter of cacophonous organic intellectual exchange by passionate, good-natured men who, though mostly unlettered – forced by poverty to leave school early for sweltering fields and stifling timber mills, or consigned to Southern chain gangs for trifling or imagined offenses to white folks’ sensibilities – they were nonetheless possessed of intuitive intellectuality, clear-eyed political instincts, and thankful appreciation for a place to unleash the soaring thoughts their workplaces had no use for. I loved their earthy speech, the poetry and drawl of their humor, the sheer musicality of their words. But no matter how their discussions began, no matter how or where they wandered, without fail they found their way to the cocoa-skinned young preacher with the sober affect and voice like cool thunder who was their Moses and Joshua both. To them his was a one-word name, a title even, intoned in their unstripped Southern accents with such breathless respect that they barely took time to pronounce it: “MarthaLuthaKang,” he was. Martha Lutha Kang. The sound of his name comforted them, inspired them, imbued them with a species of hope and pride that none but those who have been broken and reborn can rightly understand.

“MarthaLuthaKang integrated them buses and lunch counters, even got folks voting, and ain’t fired one shot. Ain’t used fist nor gun.”

“I got to give that MarthaLuthaKang a whole lot of credit, cause I’ll be dog if I’ma let some white folks beat on me until they get tired.”

“MarthaLuthaKang say it ain’t just about taking a beating. He calls it ‘nonviolent resistance’. Let white folks get all their hate out so we can all love our neighbors as Jesus say.”

“MarthaLuthaKang the only Negro that one set of white folks put in jail for a criminal and another set of white folks take out for a hero. Now, that’s integration.”

But where there are thinkers with strong passions, there is always some measure of dissent.

“Well, y’all can go on with that integration stuff if you want to. But me myself, I ain’t interested in riding nor eating with no white man. I just want somebody to integrate my money is all, turn my money green. If MarthaLuthaKang do that, I’ll eat a hamburger with George Wallace anywhere he say.”

“MarthaLuthaKang ain’t interested in no money like some of these preachers thinking they supposed to live like kings. He just wants justice in America for every colored man, woman and child. Poor white folks, too. And for all of us to love our neighbor the same way we love ourselves. That’s all he want and all he do. ”

“That MarthaLuthaKang is something else, ain’t he?”

The admiration of the barbershop men for King perched on the precipice of awe. For my part, I beheld him with the wonderment that young boys reserve for superheroes. Away from the barbershop environs I pronounced his name as it was intoned at Sunday School, on the radio and the six o’clock news. But in my heart he was who I first knew him to be: MarthaLuthaKang, who was revered second only to Jesus by everyone important in my world. So MarthaLuthaKang he remained.

Until he did not.

As I struggled through the confusions and recalibrations of pubescence, my imagination was captured by a force that changed me forever: the Black Power Movement. Its rumblings were brash, its rhetoric defiant, its styles and symbols, seductive. After a steady diet of Kingfish, Beulah, Aunt Jemima and Buckwheat, I saw young black folks standing tall, standing firm, proud of who they were and dedicated to serving their beloved and beleaguered communities; neither skinning nor grinning nor in any way paying deference where it was not due, standing up for themselves and their communities against police who sometimes would rather crack a black skull than eat lunch. When these rogue bearers of badges betrayed their oaths to protect and defend, choosing instead to brutalize and humiliate, these brave young men and women defended their communities with eloquence of speech, unwavering courage and dedication, sophisticated strategies and knowledge of the law, and the occasional fist if circumstances demanded. King’s appeals for love, for “redemptive suffering” and nonviolence –which, I realized, I’d never been fully comfortable with – now seemed both foolish and sadly weak compared to the fearless young people with their black berets, their black leather jackets, their dashikis, orbital Afros and intricate hair braiding. Martin Luther King in his funereal suits and his tradition-laden preachments did not stand a chance with urban youths like me.

So with palpable disdain I cast aside the saint of black barbershop philosophers and beleaguered black folks everywhere. But why was it so easy for me to so unceremoniously throw aside a man behind whom so many willingly ventured through the valley of the shadow of death, a man who’d long been my hero, and was still hero to so many?

I see now that I was able to dismiss him with such youthful arrogance because I had no idea who Martin Luther King really was. By then MarthaLuthaKang the venerated had been replaced in my mind by Martin Luther King the defamed and woefully misportrayed: King the “We Shall Overcome” dreamer of toothless dreams, King the world-class panderer to white largesse, King the preacher of celebrated oratory and naïve, self-abnegating pleas to embrace those who would slaughter our young and often did.

So in truth, I banned King from my pantheon of heroes because I did not know the truth: that beneath the carefully disciplined oratory, beneath his trenchant appeals to love and forgiveness, beneath the countless unchallenged beatings and homicidal assaults, in reality, Martin Luther King, Jr., was more radical than I could have ever imagined. Despite my years of barbershop tutelage and the ubiquity of his singular voice and visage, despite my certainty that the six o’clock news and Black Nationalist rhetoric had taught me all there was to know about him, it is clear now that I knew him not. Seduced as I was by the blanketing gaze of those who opposed him in life (and now misportray him in death), I had no way of knowing that when King said, “America, you must be born again;” that when he said, “You have to have a reconstruction of the entire society, a revolution of values;” and when he said, “There must be a better distribution of wealth and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism,” that in these pronouncements he was not simply talking around the edges of the challenges America faced; he was calling for sweeping changes in the very economic and political structures on which America stands. I mean, how could I have possibly known that when he said, “Our goal is to create a Beloved Community” which “will require a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives,” that he was not just spouting smarmy sentimentality, but meant instead an America radically reconfigured as an egalitarian democratic socialist political economy (with the emphasis on “democratic”), in which all of God’s children would have equal access to the fruit of the tree of life?

But now I do know. And may it be known by all that Martin Luther King was not only a dedicated fighter for racial justice. He was also a politically radical thinker who had long nursed the visionary hope of restructuring in the image of justice the economic order in this country that so routinely profits the rich and even more routinely impoverishes the poor. To one reporter he acknowledged as much. “You might say that we are engaged in a class war,” he said without remarkable boldness.

But today we have hollowed the boldness of Martin Luther King by hallowing him into America’s apostle extraordinaire of kumbiyah and teary-eyed handholding. The radicality of his vision and praxis is all but lost. Yet in these fraught times we need to reclaim the boldness and clarity of vision of the leader of the most effective movement for justice that this nation has seen, or at least be informed by it. For if the hateful, divisive campaign of Donald Trump is prologue to his presidency, we are faced with the greatest potential onslaught on civil liberties, love for our neighbors, justice under the law and social responsibility that America has endured in half a century; it threatens to rend the very fabric of our democracy society.

Martin Luther King, Jr., was slain as he forged ahead with that “class war” that still confronts us today, slain on the cusp of realizing a last dream that we must now claim as our own – a Poor People’s Campaign to press for a restructuring of America’s social architecture into a nation that will wax ever more just and ever more equitable – wax and never again wane. Not a utopia, but a true Beloved Community, imperfect yet perpetually trying to do right; ever striving through its legislated policies, its dedicated laws and most love-tempered edicts to answer the call of the prophet that long ago set King upon his own Samaritan’s road, to “let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Obery Hendricks teaches religion and African-American studies at Columbia University. He is the author of The Politics of Jesus: Rediscovering the True Revolutionary Teachings and Jesus and How They Have Been Corrupted (Doubleday, 2006)

***

MARTIN LUTHER KING MARCHES ON

by Ariel Dorfman

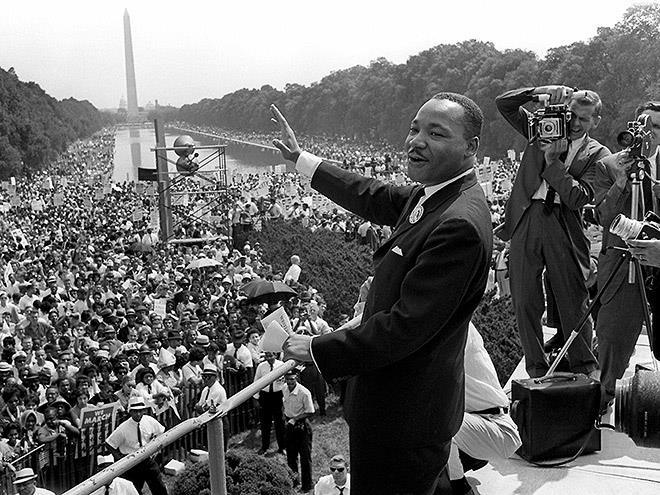

Faraway, I was far away from Washington D.C. that hot day in August of 1963 when Martin Luther King delivered his famous words from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, I was faraway in Chile. Twenty-one years old at the time and entangled, like so many of my generation, in the struggle to liberate Latin America, the speech by King that was to influence my life so deeply did not even register with me, I cannot even recall having noticed its existence. What I can remember with ferocious precision, however, is the place and the date, and even the hour, when many years later I had occasion to listen for the first time to those “I have a dream” words, heard that melodious baritone, those incantations, that emotional certainty of victory. I can remember the occasion so clearly because it happened to be the day Martin Luther King was killed, April 4th, 1968, and ever since that day, his dream and his death have been grievously linked, conjoined in my mind then as they are now, fifty-four years later, in my memory.

I recall how I was sitting with my wife Angélica and our one year old child Rodrigo, in a living room, high up in the hills of Berkeley, the University town in California where we had arrived barely a week before. Our hosts, an American family that had generously offered us temporary lodgings while our apartment was being readied, had switched on the television and we all solemnly watched the nightly news, probably at seven in the evening, probably Walter Cronkite. And there it was, the murder of Martin Luther King in that Memphis hotel and then came reports of riots all over America and, finally, a long excerpt of his “I have a dream” speech.

It was only then, I think, that I realized, perhaps began to realize, who Martin Luther King had been, what we had lost with his departure from this world, the legend he was already becoming in front of my very eyes. In the years to come, I would often return to that speech and would, on each occasion, hew from its mountain of meanings a different rock upon which to stand and understand the world.

Beyond my amazement at King’s eloquence when I first heard him back in 1968, my immediate reaction was not so much to be inspired as to be somber, puzzled, close to despair. After all, the slaying of this man of peace was answered, not by a pledge to persevere in his legacy, but by furious uprisings in the slums of black America, the disenfranchised of America avenging their dead leader by burning down the ghettos where they felt imprisoned and impoverished, using the fire this time to proclaim that the non-violence King had advocated was useless, that the only way to end inequity in this world was through the barrel of a gun, the only way to make the powerful pay attention was to scare the hell out of them.

King’s assassination, therefore, savagely brought up yet one more time a question that had bedeviled me and so many other activists in the late sixties and is repeated now in our desolate 2017: what was, was asked back then, the best method to achieve radical change? Could we picture a rebellion in the way that Martin Luther King had envisioned it, without drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred, without treating our adversaries as they treated us? Or does the road into the palace of justice and the bright day of brotherhood inevitably require violence as its companion, violence as the unavoidable midwife of revolution?

Questions that, back in Chile, I would soon be forced to answer, not in cloudy theoretical musings, but in the day to day reality of hard history, when Salvador Allende was elected President in 1970 and we became the first country that tried to build socialism through peaceful means. Allende’s vision of social change, elaborated over decades of struggle and thought, was similar to King’s, even though they both came from very different political and cultural origins. Allende, for instance, who was not at all religious, would have not agreed with Martin Luther King that physical force must be met with soul force, but rather with the force of social organizing. At a time when many in Latin America were dazzled by the armed struggle proposed by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, it was Allende’s singular accomplishment to imagine as inextricably connected the two quests of our era, the quest for more democracy and more civil freedoms, on the one hand, and the parallel quest, on the other, for social justice and economic empowerment of the dispossessed of this earth. And it was to be Allende’s fate to echo the fate of Martin Luther King, it was Allende’s choice to die three years later. Yes, on September 11th, 1973, almost ten years to the day since King’s “I have a dream” speech in Washington, Allende chose to die defending his own dream, promising us, in his last speech, that much sooner than later, más temprano que tarde, a day would come when the free men and women of Chile would walk through las amplias alamedas, the great avenues full of trees, towards a better society.

It was in the immediate aftermath of that terrible defeat, as we watched the powerful of Chile impose upon us the terror that we had not wanted to visit upon them, it was then, as our non-violence was met with executions and torture and disappearances, it was only then, after the military coup of 1973, that I first began to seriously commune with Martin Luther King, that his speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial came back to haunt and to question me. It was as I headed into an exile that would last for many years, that King’s voice and message began to filter fully, word by word, into my life.

If ever there was a situation where violence could be justified, after all, it would have been against the junta in Chile. Pinochet and his generals had overthrown a constitutional government and were killing and persecuting citizens whose radical sin had been to imagine a world where you do not need to massacre your opponents in order to allow the waters of justice to flow. And yet, very wisely, almost instinctively, the Chilean resistance embraced a different route: to slowly, resolutely, dangerously, take over the surface of the country, isolate the dictatorship inside and outside our nation, make Chile ungovernable through civil disobedience. Not entirely different from the strategy that the civil rights movement had espoused in the United States. And indeed, I never felt closer to Martin Luther King than during the seventeen years it took us to free Chile of its dictatorship. His words to the militants who thronged to Washington D.C. in 1963, demanding that they not lose faith, resonated with me, comforted my sad heart. He was speaking prophetically to me, to us, when he said: “I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow cells.” Speaking to us, Dr. King, speaking to me, when he thundered: “Some of you come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering.” He understood that more difficult than going to your first protest, was to awaken the next day and go to the next protest and then the next one, the daily grind of small acts that can lead to large and lethal consequences. The dogs and sheriffs of Alabama and Mississippi were alive and well in the streets of Santiago and Valparaiso, and so was the spirit that had encouraged defenseless men and women and children to be mowed down, beaten, bombed, harassed, and yet continue confronting their oppressors with the only weapons available to them: the suffering of their bodies and the conviction that nothing could make them turn back. And just like the blacks in the United States, so in Chile we also sang in the streets of the cities that had been stolen from us. Not spirituals, for every land has its own songs. In Chile we sang, over and over, the Ode to Joy from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the hope that a day would come when all men would be brothers.

Why were we singing? To give ourselves courage, of course. But not only that, not only that. In Chile, we sang and stood against the hoses and the tear gas and the truncheons, because we knew that somebody else was watching. In this, we also followed in the cunning, media-savvy, footsteps of Martin Luther King: that mismatched confrontation between the police state and the people was being witnessed, photographed, transmitted to other eyes. In the case of the deep south of the United States, the audience was the majority of the American people, while in that other struggle years later, in the deeper south of Chile, the daily spectacle of peaceful men and women being repressed by the agents of terror targeted the national and international forces whose support Pinochet and his dependent third world dictatorship needed in order to survive. The tactic worked, of course, because we understood, as Martin Luther King and Gandhi had before us, that our adversaries could be influenced and shamed by public opinion, could indeed eventually be compelled to relinquish power. That is how segregation was defeated in the South of the United States, that is how the Chilean people beat Pinochet in a plebiscite in 1988 that led to democracy in 1990, that is the story of the downfall of tyrannies in Iran and Poland and the Philippines. Although parallel struggles for liberation, against the apartheid regime in South Africa or the homicidal autocracy in Nicaragua or the murderous Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, also showed how King’s premonitory words of non violence could not be mechanically applied to every situation.

And what of today? When I return to that speech I first heard all those years ago, the very day King died, is there a message for me, for us, something that we need to hear again, as if we were listening to those words for the first time as we confront a danger that would make our hero shudder?

What would Martin Luther King say if he contemplated what his country has become? If he could see how the terror and death brought to bear upon New York and Washington on September 11th, 2001, has turned his people into a fearful nation, ready to stop dreaming, ready to abridge its own freedoms to be secure? What would he say if he could observe how that fear has been manipulated to justify the invasion of a foreign land, the occupation of that land against the will of its own people? What alternative way would he have advised to be rid of a tyrant like Saddam Hussein? Would he tell those who oppose these policies inside the United States to stand up and be counted, to march ahead, to never wallow in the valley of despair? And Trump! Trump who soils his mouth by quoting Martin Luther King, Trump, who believes that Frederick Douglass is still alive, who insults the heroic John Lewis as someone who is all talk and no action, mocks John Lewis who was beaten by the police on freedom marches and risked his life, Trump, what would Martin Luther King say to an America that has elected Trump to occupy the office that saw the Civil Rights Bill signed?

It is my belief that he would repeat some of the words he delivered on that faraway day in August of 1963 in the shadow of the statue of Abraham Lincoln, I believe he would declare again his faith in his country and how deeply his dream is rooted in the American dream, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, his dream was still alive and that his nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘ We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.’

Let us hope that he is right. Let us hope and pray, for his sake and our sake, that Martin Luther King’s faith in his own country was not misplaced and that more than five decades later enough of compatriots and mine will once again learn listen to his fierce and gentle voice calling to them from beyond death and beyond fear, calling on all of us to stand together for freedom and justice in our time.

Ariel Dorfman is a Chilean-American author, whose books have been published in over fifty languages and his plays performed in more than one hundred countries. Among his works are the play Death and the Maiden and the memoir Heading South, Looking North. His most recent work is the collection of essays, Homeland Security Ate My Speech: Messages from the End of the World (OR Books) and the forthcoming novel, Darwin’s Ghosts. He contributes to major papers worldwide, including frequent contributions to The New York Times. He lives with his wife Angélica in Chile and Durham, North Carolina, where is the Walter Hines Page Emeritus Professor of Literature at Duke University.

THANK YOU TIKKUN for sharing these powerful energetic hopeful words/actions.

— Ron Bell

Excellent article. He was the most influential person in my life.