North American Levinas Society 2020 Online Conference

THE FACE AND THE INTERFACE: Levinas, Teaching, & Technology

Panel 11: Confinement and Poetics in Levinas, July 23, 2020

In Memoriam Helen Pinkerton, poet, mentor, and friend extraordinaire

My paper reflects on how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected my teaching, reading, and writing over the past several months. I will begin by reflecting on how the onset of the pandemic has affected my teaching. During spring quarter, I was scheduled to teach a class on Levinas and Tolstoy in prison to a mix of university students and inmates at the Oregon State Penitentiary through the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program. The essence of the class is the face-to-face encounter of inside and outside students. In my Inside-Out classes, we both read Levinas on the face and enact the face-to-face encounter. Students sign up for the class because of the opportunity it offers them to be turned inside-out by the face-to-face encounter. I decided to cancel the class rather than teach it remotely to university students who would be deprived of studying with their peers on the inside, even remotely, as the incarcerated students do not have access to the required technology.

Not teaching the class allowed me to focus more intently on the Daf Yomi project, often called the world’s largest book club. Those participating in this ambitious effort read a folio page (a “Daf”) of Talmud a day (“Yomi”) with the aim of completing a reading of the entire Babylonian Talmud in seven and a half years. My goal has been to write a poem a week, mainly in meditative blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter), on a passage from the week’s reading in the Talmud. In my presentation today, I will read aloud and comment on four of these poems.

Before turning to the poems, I will say a few things about Levinas and poetry. Despite the skepticism Levinas expresses about poetry in essays such as “Reality and its Shadow,” Levinas was himself haunted by poetry, by specific lines of poetry. I think, for example, of his decades-long rumination over two lines from Paul Valéry’s poem Cantique des colonnes: “C’est un profond jadis,/ Jadis jamais assez! [“A deep long since it is,/ Never long since enough!”]. Levinas’s rumination begins in his discussion of the dwelling (la demeure) in Totality and Infinity, but it finds its definitive importance in his oeuvre first in his essay “Signification and Sense” (1964) and, later and most crucially, in his discussion of recurrence in Otherwise than Being (1974). There Levinas argues that what recurs in consciousness, as it constitutes itself in the present, as it collects itself and recollects a past, is the sense that this supposedly pure consciousness – a consciousness allegedly concerned primarily with knowing – is in fact haunted by its prior responsibility for the other.

In regard to the question of Levinas and poetry, let me take this opportunity to confess that one of the pleasures of reading Levinas, for me, is the poetic evocativeness of his prose. For me, Levinas, like Plato, is a poet-philosopher. Consider the evocativeness of the title of Levinas’s second great work, Autrement qu’être, a title that bears witness to its author’s having been haunted by a pentameter line from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, “To be or not to be, that is the question.” “Être ou ne pas être – la question de la transcendence n’est donc pas là [“To be or not to be is not the question where transcendence is concerned],” Levinas writes, in response to Shakespeare, in the first sentence of the second paragraph of Autrement qu’être. If the title of Levinas’s second major text is a poetic evocation of Shakespeare, the philosophical poet par excellence, the book’s subtitle, “au-delà de l’essence [beyond essence],” is a poetic evocation, via a direct translation, of what Glaucon calls the ludicrously hyberbolic phrase “beyond being” (ἐπέκεινα τῆς οὐσίας) coined by the poet-philosopher Plato, to describe “the Good” in the sixth book of The Republic (509c).

Levinas often talks about the difference between the universalism sought by Greek philosophy, on the one hand, and the cultural particularism of Jewish texts, on the other. Levinas speaks of the challenges of translating Hebrew into Greek, and much of the innovative quality of his philosophical writings is the result of this effort of translation. Levinas was unusual as a Talmudic reader and commentator in his insistence on reading the Talmud’s cultural particularism in a way that reaches beyond a particular ethnic group towards a broader humanity. Levinas insists that, when encountering the Talmud, the reader is free to understand “Israel,” or Israelite, as “human being,” representative of “a human nature which has reached the fulness of its responsibilities and of its self-consciousness . . . . [T]he heirs of Abraham are all nations; any man truly man is no doubt of the line of Abraham” (New Talmudic Readings xxix-xxx).

I conceive of my “Talmudic Verses” series as poems composed within the Greek tradition. Indeed, the word “poem” is derived from the Greek word poiema, meaning something made. Aristotle, the most influential thinker in the history of literary theory and criticism in the West, in the ninth chapter of his Poetics (1451b) defends poetry (poiesis) as speaking of things in a manner that is more universal (katholou) than history, which speaks in a manner that adheres to the particular (kathekaston). In his Talmudic readings, which he approaches from a philosophical perspective, Levinas tries, as he puts it, to translate Hebrew into Greek, to translate the particularity of the Jewish tradition via the universal language of philosophy. This is how I conceive of my “Talmudic Verses”: they translate the Hebrew (and Aramaic) of the Talmud into the universalizing — the “Greek” — language of poetry, thus attempting to make the Talmud accessible to those living beyond the Talmudic orbit.

The first poem I will read aloud to you, Talmudic Reading: Shabbat 88a, was composed in response to a section of the Talmud on which Levinas reflects in his essay “The Temptation of Temptation.” My poem, which draws on Levinas’s inspired reading as well as on my own encounter with the Talmudic text, builds up to a reflection on the relation of the Talmudic passage to the murder of George Floyd and to the massive protests that followed in the wake of that ghastly and barbaric murder, all in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. The protests are, I suggest, the righteous response of those who saw (mainly via recorded video images), and felt commanded by, the vulnerable face of George Floyd. The opening lines of the poem refer to the famous words “na’aseh v’nishma,” “we will do and we will hear/understand (Exodus 24.7),” uttered by the Jewish people at Sinai, as they consent to accept the Torah before investigating, thoroughly and precisely, just what it is that they are about to take on.

Talmudic Reading: Shabbat 88a

When Israel accorded precedence

To “we will do” over “and we will hear,”

Consenting to receive the holy Torah,

The ministering angels came and tied

Two crowns to each and every Israelite.

So Rabbi Simai taught, and Rabbi Chana

Agreed, citing a verse from Song of Songs:

“Just like the apple tree among the trees

Of the forest” is God’s love for Israel,

For as the fruit grows on an apple tree

Before its leaves appear, so did God’s people

Say “we will do” before “and we will hear.”

“You Jews are headstrong,” said a naysayer,

“You leap before you listen, saying yes

To Torah, taking on the burden of

Responsibility before you weigh

The consequences of your hasty choice!”

Now in this time of plague, of distancing,

Of masks and calls for prudence, the brave young

And the incautious old, Israel’s heirs,

Gather, a storm of holy protest, having

Seen the black face of innocence betrayed

While the brave young and the incautious old

Continue tending to the sick and dying.

Another poem comments on a Talmudic passage (Shabbat 105b) in which the rabbis discuss whether or not rending your garment, in response to the news of the death of a loved one, is permissible on Shabbat. The rabbis here make a distinction between constructive and destructive actions. Constructive actions are, generally, forbidden on Shabbat. Shabbat is a time to appreciate and enjoy the created world rather than to engage in acts of human creation or construction, as the rabbis discuss earlier in the treatise (73a), on which I comment in the following brief poem, which coins a new verb, “to new,” that is, to create something new:

Today is Sunday, time to write, to do,

And so I pen these novel lines to you.

On Shabbos I will rest and cease from newing,

A human being, not a human doing.

To return to the more somber context of Shabbat 105b: the tearing of a garment, the rabbis argue, is a destructive action, and is therefore permitted. Indeed, they argue, I am obligated to mourn a close relative in this way. But am I obligated to mourn others, to extend my sympathies beyond my immediate family? And if so, just how far must I extend my sympathies? That following poem describes how the rabbis of the Talmud respond to this question:

Talmudic Reading: Shabbat 105b

I am obliged to mourn, tradition states,

If the departed is a close relation:

Spouse, mother, father, daughter, sister, son.

Sensing that this is not quite right, the Rabbis

Ask whether I am not obliged to mourn

Not only relatives, but Torah scholars.

The Rabbis answer yes, though this might seem

A judgment tarnished by self-interest as

The Rabbis are all Torah scholars, so

They push ahead with yet another question.

If the deceased is not a Torah scholar

But is an upright person, must I mourn?

Yes, they decide. And what if I don’t know

If he was righteous, but if I am standing

Over him as his soul departs, am I

Obliged to mourn for him? The Rabbis say

Yes, I must mourn for him as I must mourn

A Torah scroll that has been burned, for Torah

Teaches I must be loving towards my neighbor

As if that very loving were the meaning

Of “I,” as in Hineni, “Here I am!”

If I am standing over him and hear

My neighbor utter “I can’t breathe” and witness

His final breath, I am obliged to mourn

And even to protest, be it in a plague,

So the arc of history may bend toward justice.

It is as if, in the midst of this terrible pandemic in the United States, the American people have been forced to pause, to stop doing, to allow themselves – to allow ourselves – to be vulnerable. Some have reacted, and continue to react, to this vulnerability with fear. But it has been remarkable how many millions of Americans, having witnessed the death of George Floyd, stopped to ponder just how widespread and, yes, how systemic, racism still is in the United States of America, how deeply ingrained it is in the history and in the economy of this particular nation. The dominant moral mood of the nation appeared to shift, almost overnight. Will it last? That remains to be seen. But the eruption of the goodness of millions of ordinary citizens that we have witnessed, in the midst of this terrible plague, is truly extraordinary, is indeed breathtaking.

“Only a vulnerable I,” Levinas has remarked, “can love his neighbor” (Of God Who Comes to Mind, 91). This vulnerability and this love is, of course, what the Torah commands and to which, according to Rabbi Hillel in the Talmud, all of the Torah can be reduced. Levinas famously remarked that Judaism is a religion for adults, but these adults are referred to throughout the Torah as “children,” b’nei Israel, the “children of Israel.” Children, in their innocence and openness, embody this virtue of vulnerability; and they evoke, in those of us who aspire to be adults, a sense of responsibility that compels us to protect our children, and the children of our neighbors, from harm. The current administration in Washington, D.C. is angering many American citizens by threatening to withhold federal funding from the schools if the students don’t return next month, regardless of how fiercely and uncontrollably the pandemic is raging, thus putting the lives of millions of vulnerable children, and their teachers, at risk.

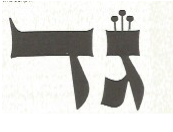

I will conclude this presentation with a poem from “Talmudic Verses” that comments on a Talmudic passage that responds to the remarkable wisdom of some children, young and vulnerable, who have just visited the beit midrash, the study hall, and who have shared their feelings about the sounds and images of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Before I read the poem, please have a look at the letters Hebrew letters gimmel and dalet, upon which the children reflect in this passage from the Talmud:  Take note of how the letter on the right, the gimmel, appears to be walking or running towards the letter dalet, to its left (remembering that one reads, in Hebrew, from right to left):

Take note of how the letter on the right, the gimmel, appears to be walking or running towards the letter dalet, to its left (remembering that one reads, in Hebrew, from right to left):

Talmudic Reading: Shabbat 104a

The Rabbis told Yehoshua ben Levi:

First-graders came to study hall today

And said things unlike anything you’ve heard

Even from Joshua, the child of Nun,

Moses’ disciple, who would never leave

His tent of study in the wilderness.

These children in the study hall explained

The sounds and the designs of Hebrew letters,

Taking them two by two and pondering

How each in every pair relates to the other,

Each child a Noah of the alphabet!

The first pair, Aleph-Bet, they said, means Alaph

Bina, “Learn wisdom,” wisdom of the Torah.

The second pair is Gimmel-Dalet, meaning

Gemol Dalim, “you must give to the poor.”

The gimmel’s leg, they said, is walking towards

The dalet as a kindly person seeks

The poor. So Abraham rushed from his tent

To welcome strangers in the heat of day,

Imploring them to stop and have a meal

Though Abraham, at ninety-nine, had just

Been circumcised, a child of Israel,

Feeling the pain of others as his own.