For my parents, Aileen Gluck and Stan Gluck z’l

Shortly after the birth of my grandparents, W. E. B. DuBois presciently declared in 1903 that “The problem of the twentieth century is the color line.” DuBois articulated a persistent social fact for people of color, one that many whites assert plays little or no role in their lives.

I have sought, for most of my life, to understand how the past two generations of my family of origin — Jewish and, in the American racial binary, white — underwent a series of perceptual transformations in its racial understanding that seems to have evaded many of their peers. Many years of intimate personal encounters and collective experiences informed their racial consciousness. Our perceptions of race matter in a country where race remains an often-unspoken determinant of meaning, access, and identity.

1. Origin stories

For each of my grandparents and parents, life presented unanticipated decision moments whose implications were rarely clear at the time. Yet the consequences reverberated through the rest of their lives and into mine. Let me tell you some stories.

i. Dad

Amidst the raging war against Germany, my father, a skinny 18-year old Jewish man from the Bronx, consumed gallons of water to tilt the scales above the 105-pound draft minimum. He wanted to join the fight against the Nazis. After embarking from Fort Hamilton, Brooklyn on November 6, 1943, rough seas and German torpedoes greeted the U.S.S. Robin Sherwood on route to Cardiff, Wales. Dad recalled hours spent heaving over the side of the ship during the four-week passage, as the boat passed the remains of less fortunate vessels.

My father on a bench in Paris, 1945

Before departing for Europe, Dad underwent basic training at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. In the Army, he entered an environment that was hostile to Jews. His experience was dominated by the sexual taunts and predation of a commanding officer and fellow soldiers. Ironically, his initiation to American masculinity came not at the hands of the Nazis but from white Christian Americans. Dad’s time in the Army left few warm memories. His service remained for years a constant acidic irritant.

A defining moment in Dad’s life occurred during basic training. On a day off, he walked to a restaurant near the base. Dad and a Black fellow soldier approached the entrance at the same time. Dad’s previous experience with people of color was very limited. His Bronx, New York classmates were all white; many had names like Kujawski, Powder, and Gambino; some, like Gimbel and Goldman were Jewish. The schools he attended, including Evander Childs High, remained racially segregated until the 1950s.

It seems unlikely that the two soldiers knew one another since Army units remained segregated until 1946. They were denied entry as a pair, but the maître d’ beckoned Dad to a table on condition that he entered alone. The Black soldier was directed to leave the premises. Dad told the restauranteur that they would either eat together or not at all. Dad turned and walked out. Presumably, the two soldiers each went their own way. I wonder if they spoke, and if so, what was said.

I’ve found among Dad’s papers hints of an early awareness of race. Dad began to paint by the time he was fourteen. One of his first canvases depicts Huckleberry Finn, awash in pastel colors and wearing a torn shirt and lantern-lit hat. Huck is standing on the deck of a raft; his loyal African American friend Jim sits at the far end of their onboard sleeping tent. On this dark riverboat night, Jim’s eyes gaze into the expanse beyond the deep blue river. Dad’s attention to Jim’s reflective mood suggests to me Dad’s fascination with his character, however little is revealed about of the contents of Jim’s thoughts. Maybe Dad identified more with the pensive Jim than with the mischievous Huck?

Dad’s gesture of solidarity with the Black soldier was surely an act of simple decency; to this 19-year old Jewish man, nobody deserved any less than their fellow. Orphaned at age three and rescued by a caring aunt and uncle, personal misfortune had already taught him what it felt like to not be the master of one’s own fate. What emerged at the Kentucky restaurant would become Dad’s lifelong instinct to protect vulnerable people. He would not be indifferent in the face of unfairness.

Surely in Kentucky, if not the West Bronx, the norm would have been to look the other way. As a Jew, Dad was aware of his own vulnerability. Five years after painting Huck and Jim, now in basic training in Kentucky, Dad felt a deep revulsion at his first encounter with Jim Crow. He gained a steely ethical barometer as a guide.

ii. Mom

My mother was born in 1927. Like Dad, she was raised in the Bronx, relatively insulated from politics. Mom’s parents were born on New York’s Lower East Side. Each of Mom’s grandparents immigrated from Eastern Europe around 1880. Her paternal grandfather, Yitzhak Abba Cohen traded identity papers with a man named Abraham Yitzhak Kaplan so he could flee to avoid the 25-year Russian army draft. Abba and his wife Yenta, now in New York, were impoverished refugees who neither left the Lower East Side nor became naturalized citizens.

Memories of Mom’s grandparents’ immigrant experience remained with her as she worked post-college. Mom wrote and edited papers on American life for new Americans at the Common Council for American Unity. The office was located at Freedom House, across from the 42nd Street Library. Destructive Cold War political crosswinds, unbeknownst to her, impacted how her mentors perceived the organization’s work. In 1948, soon after graduating college, Mom attended a talk at a Hunter College alumni event. The speaker urged Americans to build close relations with anti-communist post-War Germany, and to welcome their scholars. My mom raised her hand to question the wisdom of this strategy until such a time when de-Nazification was complete. The speaker silenced her. After the talk, as she moved towards the exit, the History Department chair chastised her for her work at the Common Council. She was told later that her “pro-communist remarks” at the talk ruined her chances of ever teaching at Hunter, her alma mater.

Mom and her younger sister Myra had one particularly meaningful point of contact with a Black professional during their childhood. Piano teacher Miss Alfreda Brown had a studio on Edgecombe Avenue, in the famous Squirrel Hill neighborhood of northern Harlem. Squirrel Hill, particularly Edgecombe Avenue, was home to prominent Black intellectuals, artists, and sports figures. Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Aaron Douglas, Roy Wilkins, W.E.B. DuBois, Kenneth Clarke, Jackie Robinson, and Thurgood Marshall were neighbors. Miss Brown’s nephew was a lawyer. Most of her students were Black.

My mother and her sister visiting Miss Brown in the 1960s

Miss Brown offered the equivalent of a small music school: private piano lessons, and ongoing semester-end recitals. She supported her studio by sponsoring student studio recitals. At times, these took place at Carnegie Recital Hall, next door to the famous eponymous cathedral of Classical music. Mom’s aunts, particularly on her father’s side, regularly bought tickets, despite the disparaging racial comments some of them made in other settings. Thus, the family regularly spent time in Harlem, well into the period when the demography of the neighborhood had turned from substantially Jewish to mostly Black. Separated by a bridge, 155th Street connected Edgecombe Avenue in Manhattan with Jerome Avenue in the family’s Bronx neighborhood. The East River represented something akin to a Mason-Dixon line between Harlem and the West Bronx.

Mom remembers, during the 1930s and 40s, regularly seeing lines of young Black women seeking day labor three blocks from her apartment. This seemed unremarkable to the family because it had become a regular feature of economically aspiring Jewish families, even those of limited means, to hire African-American domestic day workers. At some point, Grandma and Grandpa hired Wilhelmina Douglas as a domestic. She subsequently began to work for my parents, too.

My mother has, from this same period, a poignant memory of her mother feeling racially stigmatized. Grandma Essie’s first child, my mother, was light skinned. But Grandma was of darker complexion, and her eyes were Asian in appearance. When she pushed Mom’s baby carriage along the Grand Concourse, the glances of passersby conveyed the message, told my mom, that people thought she was a nursemaid.

My grandparents, early 1920s

The broader culture grudgingly welcomed my grandparents and their siblings as they began to assimilate within American society. Some family members carved out niches within the garment and fur industries. As workers, they unionized and gained a modicum of political and social stability. This could sometimes involve bloody struggle, as attested by the Triangle Fire. The price of relative success was a tacit agreement to become Americans of a Jewish “persuasion” rather than part of a Jewish peoplehood. The result was a hybrid insider-outsider status, American but not Christian and, provisionally, white.

2. Domains and boundaries, the older generation

The growing national cultural understanding at the time was not the multiculturalism of today but of an American melting pot. My grandfather’s family and, to lesser and varying degrees my grandmother’s, accepted the model of social acculturation, knowing that they would remain an exception within the fabric of Christian America. Yet whiteness remained the unspoken determinant of insider status. Assimilating and accepting increased access to resources and privilege translated into becoming “white.” This normalized their status as Americans but placed them in an uneasy position relative to Black America.

My grandparents felt a strong pull to gain social acceptance. Their parents arrived on these shores seeking safety, security, and economic improvement. My grandparents were raised in an impoverished ghetto on the Lower East Side of New York. They had few hopes for upward economic movement in the Bronx and Brooklyn, choosing instead to prioritize their daughter’s education and preparation for white collar professions.

As my grandparents’ generation, and then their children, moved into increasingly residential neighborhoods, Black people became the new residents of formerly Jewish neighborhoods. The Black Great Migration of the 1920s-1940s immediately followed the mass movement of Eastern European Jews to the United States during the 1880s-1920s. In a society defined by a racial binary, whiteness gained Jews increased social acceptance, while shielding them from the burden conferred by blackness. Discrimination continued to prevent Jews from entering professions and neighborhoods into the 1960s, but skin color became the marker that reduced the stigma of Jewish difference. The presence of Blacks thus helped Jews find protection from the insecurity and dangers of institutional racism.

My grandfather’s sisters referred to Blacks with the Yiddish epithet shvartze, a term not tolerated in my grandmother’s own home. Shvartze referred to a specialized subset of non-Jews, literally “black” (skinned), people with lower social status, but those perceived as less dangerous than white Christians (who had historically been the major threat to Jewish life in Europe). The term shvartze, however, employed images deeply embedded within American culture equating blackness with danger. Separation from African Americans helped designate Jews as socially acceptable while reinforcing a Jewish understanding that all potential sources of danger were to be avoided. Black people could be treated kindly so long as a boundary was maintained between employer and employee.

Blacks were viewed as peers only on the Jewish left; my extended family members were Roosevelt Democrats, not engaged political actors. My grandmother’s attitudes were far warmer towards Black people; she expected ignorant comments from some of her sisters and sisters-in-law. She held her peace with her relatives and imagined a better world for her daughters and a time when racial divisions would fade away. My parents’ growing activism was never discussed at Seder, while my grandparents were anxiously supportive. My grandmother’s social consciousness, her openness to Miss Brown, and her sensitivity to vulnerable non-Jews seems remarkable and unanticipated in the context of her generation. Late in her life, she became a secretary at the Common Council, the same office that had employed my mother during her college years. Grandma’s most significant legacy might be the transmission to her daughters and grandchildren values of equality, inclusion and fairness

3. Goldens Bridge

My parents, my brother, and I spent our summers from 1958-1963 at a summer lake community an hour north of New York City. Distinctly Jewish and affirmatively secular and political, the Goldens Bridge Colony was founded by a small group of Jewish immigrants. The site was a former dairy farm (owned by a Jewish farmer) in walking distance of the New York City commuter train. The men were well-educated professionals, some of them dentists. The women included sweat shop workers. Together, Goldens Bridgers aspired to build a democratic, egalitarian, and caring cooperative community. Construction of the first bungalows began in 1927. By the time we arrived in 1958, the small homes had electricity and running water. Dirt roads accommodated pedestrians and automobiles.

Goldens Bridge Camp, 1960. I am second from left, in the front.

Before World War II provided a unifying patriotic theme, townspeople were hostile to the Colony. An early member recalls:

“Our mothers used to wear halters and shorts and go walking down the road singing Russian and Yiddish songs. The people of the town, they objected to the people of Goldens Bridge. They demanded that we wear skirts when we went to town and behave like ‘real Americans,’ whatever that was. Anti-Semitism remained pervasive in the region.”

Indeed, older members found in the Colony a spirit, Yiddish language, progressive political sensibilities, and the need for collective defense from a hostile world, in a sense, a utopian version of their shtetls in Eastern Europe.

My parents didn’t at first understand the political nature of Goldens Bridge. They had been invited by close friends whose (Communist Party) politics was as unfamiliar to them as was Jewish secularism. Many Golden Bridge families were Socialists or Communists, active in social movements of the day. During the 1930s, New York City Labor union picnics took place in the Colony. Young adults from the Colony fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Political speakers often came to give talks; singer/organizer Pete Seeger was a regular visitor. In 1949, when Paul Robeson sang at a rally in nearby Peekskill, a contingent of Goldens Bridge people rallied in support.

One Tuesday evening in 1960, historian Herbert Aptheker, author of important books about slave revolts and other aspects of Black history, gave a talk about why he was voting for Kennedy over Nixon in this “Capitalist, imperialist…” country. Late that night, Mom’s friends schooled and soothed her nerves with a seminar about the Hollywood Ten, a group of writers, actors, and directors who were blacklisted during the McCarthy era. Members of the group had hidden out in Goldens Bridge.

During my family’s years at Goldens Bridge, McCarthyism was winding down, and the Civil Rights Movement was rising. Funds were raised for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Busses of adults and teens from the Colony traveled to the 1963 March on Washington For Jobs and Freedom. My brother and I were quite young, six and eight, so we watched on the small black and white television in our cottage. The image was barely visible through the crackly snowy interference.

My first musical memories were built at Goldens Bridge. During special Saturday night events in the barn, we sung folk songs and Freedom Songs, the music of the Civil Rights Movement. On a couple of occasions, these songs, “Ain’t Nobody Gonna Turn Me Around,” “If I Had a Hammer,” “Michael Row Your Boat Ashore,” “We Shall Overcome,” spurred on Freedom Riders departing on perilous journeys into the Jim Crow south. My memories of these songs fill me with excitement and warm recognition yet evoke a tinge of anxiety. The Riders told stories about the tremendous violence they anticipated; this was a music of resolve and hope in the face of terror. When I think of music, even today, it is this particular music that first comes to mind.

The most pervasive quality of Goldens Bridge was its cooperative spirit and sense of belonging. While members of the Colony held issues of equality close to their hearts, few Black families were among us. Our next-door neighbors were a prominent Black family but otherwise, the handful of Black families nearby were not part of the Colony. Racial integration had not arrived at progressive Goldens Bridge.

4. School integration in Queens

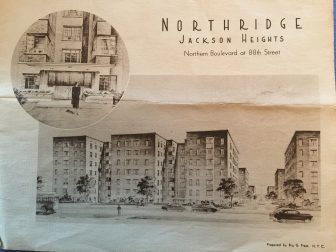

For the first four years of’ their marriage, in 1947, my parents awaited the construction of Northridge, the apartment cooperative where I spent my first eleven years of my life. While awaiting construction, they lived with my grandparents in the Bronx. I was born four years after the move, followed two years later by my brother. Northridge featured a cooperative nursery school whose students were substantially white and Jewish; our head teacher was Black.

My mother and me, 1956

Northridge, promotional brochure

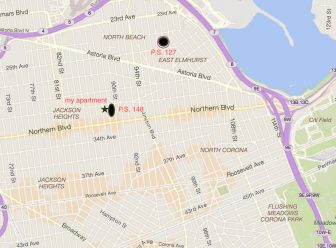

Northridge is located within four square city blocks, between 88th and 92nd Streets, immediately north of Northern Boulevard. Northridge straddled the Queens neighborhoods of Jackson Heights and East Elmhurst, and each contained an elementary school. East Elmhurst wedged between Corona and Jackson Heights, lay under the flight path of LaGuardia Airport. It was home to Black cultural luminaries including Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Harry Belafonte, and from 1959-1965, Malcolm X (ten blocks from my apartment building). Jackson Heights was predominantly white. The decade-plus separation between our sliver of northern Jackson Heights and East Elmhurst would be challenged in 1963 by a forward-thinking school integration endeavor, the Princeton Plan. My family’s perceptions of the coming change were influenced by our experience of the Civil Rights Movement, while at Golden’s Bridge; activism was now meeting the daily reality of Queens.

Map of Queens, New York: East Elmhurst and Jackson Heights

99th Street East Elmhurst

New York’s school integration program, proposed in 1963, paired the elementary school across the street from our apartment, P.S. 148, with P.S. 127, about fifteen blocks away, in East Elmhurst. Initial plans for a New York City school integration plan date back to 1955, soon after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, which found school segregation unconstitutional. The New York Board of Education presented a limited plan. In response, pastor Milton Galamison organized a school boycott in February 1964. The next month, fifteen thousand white mothers belonging to a group called Parents and Taxpayers marched to City Hall in a counter demonstration against school integration.

My parents were strong advocates in favor of the Princeton Plan. My mom was Queens Women’s Division president of American Jewish Congress, then a civil rights organization, and chair of our cooperative nursery school. She and a close Northridge friend partnered with the East Elmhurst Parent’s Support Committee. The result was successful advocacy and lifelong friendships. One of my earliest memories visiting our closest new family friends focuses on the movie “Shaka Zulu.” I recall sitting with their son Tony, together loudly rooting for the Zulu warriors as they were decimated by the Europeans.

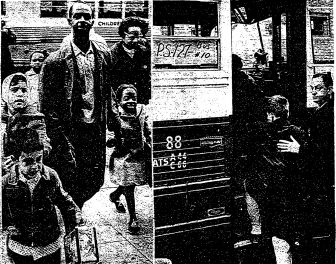

Image 9: Two images of opening day of school integration. Left: students with parents arriving at P.S. 148 across the street from my house. Right: my father assisting a children enter a bus headed to P.S. 127.

On the first day that five- and six-year-old children arrived on busses from East Elmhurst, dozens of members of Parents and Taxpayers massed, screaming in favor of “neighborhood schools.” They held signs opposing bussing. Dad remembers carrying children off the buses and through the hostile crowd, many of them were from outside the neighborhood. NBC TV Nightly News correspondent Gabe Pressman stood in front of our house, interviewing opponents. When my parents confronted Pressman, to ask why he wasn’t speaking with supporters of the Princeton Plan, he said: “people who obey the law don’t make the news.” My Dad asked whether Pressman would return if the plan succeeded. Dad always bitterly recalled the correspondent’s negative response. My brother came home one day, confused after being loudly called a “son of a Communist!” while walking home. He asked Mom, “what’s a Communist?”

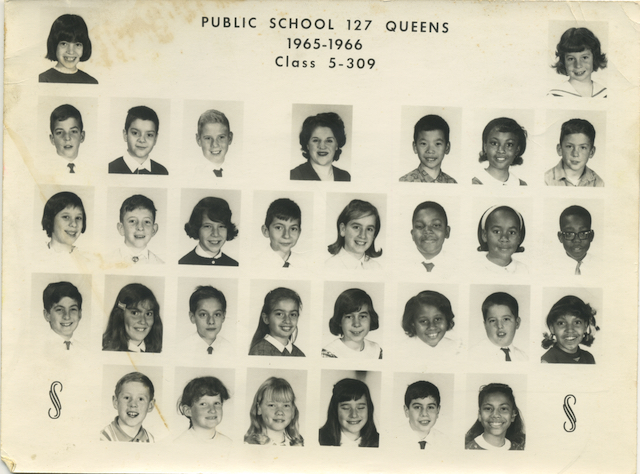

Despite the conflicts, the children’s friendship circles easily crossed racial lines. The antipathy of local parents eventually receded in the face of the overwhelming success story. The experiment in inclusion and integration lasted for several years, imprinting a lasting impression on the children.

Image 10: My fifth grade class at P.S. 127. I am in the second row from the bottom, third from left.

5. Racial complexities for middle class whites and domestic workers

When I was very young, my parents hired Wilhelmina Douglas, the African American woman who had worked for my grandparents, to clean our apartment each week. One year, when my mother taught full-time, Wilhelmina came every day to welcome my brother and I home from school. She was, for many years, the most constant presence in our home, beyond our immediate family.

The seeming intimacy I perceived was filtered through the professional relationship and of course, vast differences in power. Despite the many hours I spent with Wilhelmina (never Mrs. Douglas), I knew little about her as a person. At home, we never discussed there being anything worthy of mention about the dynamics. I recall my parents always treating her with respect, trust, and kindness. One day, Wilhelmina and I were in our apartment. The television set was tuned to news of police attacking civil rights protesters in Alabama. Wilhelmina spoke of the protestors with derision, expressing concern that it was not good to make waves. She said that people were just people and one shouldn’t highlight differences or publicly air problems. It was better to not call attention to difficulties; one should just work hard and keep moving forward. Within a few years, I came to the realization that my family lived a kind of double life, and this troubled me.

6. Differing perceptions about school integration

Years later, I asked my Mom and her East Elmhurst partner, Dorothy, to explain their respective perspectives about the Princeton Plan. While Mom always continued to believe that racial integration could save the country, Dorothy felt that the pairing with a lower middle-class white school was not an example of uplift, but rather, a watering down of a strong, independent, economically successful Black community. For our family, the integration plan cemented Mom’s political insights gained at Common Council and at Goldens Bridge. For our family, being an American Jew had come to mean striving for racial justice. We also realized that a society that could open the doors of inclusion to Blacks would also remain a multicultural culture that was safe for Jews.

Our East Elmhurst family friends, the Puryears, 1980s.

Four months into the inaugural year of the school pairing, shortly after I turned ten, the murder of Malcolm X shocked our community. My strongest memory of that day, beyond the news headlines in the New York Post, is the piercing wail of our downstairs neighbor, standing in front of our building. Her son was Malcolm’s daughter’s friend and classmate (as was my brother). The content of her screaming was disturbing: “They killed her father!… she is a shvartze!” My heart sank when I realized that her outburst was less a response to the violent murder than it was about her son’s closeness to a Black girl.

The elementary school administration provided strong support for Betty Shabazz (aka Mrs. Malcolm X), keeping the press and intruders away from their children. But not long after, the Shabazz family moved to Mount Vernon, a southern Westchester County town with a strong upper middle-class Black neighborhood. There, they found solace in their friendship with Nina Simone.

7. Sexism and family transitions

The next year, my family’s life dramatically changed. My mother was been a Social Studies teacher, with a specialty in American History, but she lacked a full-time license. Mom began substitute teaching when I was a few years old, but once my brother was well into elementary school, she longed to return to full-time teaching.

A decade prior, Mom had failed her New York City licensing test for high school Social Studies certification. She took the written exam when she was nine months pregnant, and a few months later, with me in the bassinet, she prepared her sample classroom lesson. Unlike the men, whose teaching demonstration aligned with their field of American History, Mom was assigned a class on the thesis: “How the British Empire has adjusted to colonial nationalism.”

My mother dutifully prepared a lesson plan comparing the colonial experiences of Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, Pakistan, Ceylon, and other countries within the British Commonwealth. This was a topic about which neither she nor the students knew anything. In class, they started blankly at her questions. It was, in Mom’s view, a setup. The testers reported: “unfortunately the candidate lectured for a least a minute befor (sic) asking the question: with the result that most pupils were not stimulated by it… A most serious weakness was the failure of the candidate to draw more than half the pupils into the lesson at all. She tried calling on non-volunteers a few times but drawing no response from several, relied on volunteers, many of whom were not called on by name…”

Mom’s page-long rebuttal failed to gain traction, so she remained a substitute teacher. One day, a colleague suggested that she respond to ads for teaching job in Northern Westchester County. The results of her teaching test would not prove to be an obstacle in districts outside New York City. I didn’t understand at the time why my family would choose to move to the suburbs. We were quite happy in Queens, neatly balanced by summers in the country. I guessed that my father might have yearned for green spaces, having known few as a child. But the real answer was gender discrimination. After looking at several houses, we chose one in between the towns of Mount Kisco and Chappaqua. The alcoholic owner of the home had been unable to prepare the home for sale. It was priced low, so we wrote a deposit check. Back in Queens, we packed our belongings. The movers arrived. All too quickly, the van was sealed shut. I waved to my friends from the window of our 1961 Pontiac Catalina in July 1966, and we drove off.

8. Entering a different kind of neighborhood

Our new next-door neighbors welcomed us with seeming warmth. Their limited experience with Jews became apparent when they told us that another family had just moved in around the corner, and surely, we’d have much in common. What that meant was simply that the new family was Jewish. Restrictive covenants barring Jews and Blacks continued in force in town. The deed on our home stipulated that members of neither group could sleep on premises overnight. I was befriended on the first day of school by a blond haired, blue eyed boy who introduced himself as a Jew (he wasn’t) so I shared with him much about my life. I spoke about the park across the street from our apartment, Hebrew School, the Princeton Plan, my Black friends, and about growing up not far from Malcolm X. This was our first and last conversation; later I realized that he was merely collecting information.

Around that same time, the local private garbage company unloaded a truckload of filled trash bags into our driveway. I was afraid Dad would be angry, so I quickly cleaned up the mess after school, leaving not a trace. On our first Halloween night, Molotov Cocktails were thrown at me by a laughing group of boys. I quickly realized that I was truly on my own in a hostile environment.

9. Finding solace in big city racial politics

Every weekend, I attended the Julliard School of Music Preparatory (now Pre-College) Division in New York City. I began in third grade and continued after our move. At the time, the school was located on 120th Street and Claremont Avenue, in Morningside Heights. My train stop was at 125th Street, in Harlem, so I spent much of my free time on Saturdays in 1968-1970 walking the streets of Harlem. Hawkers were selling the neighborhood newspapers: The Black Panther, Amsterdam News, and Muhammad Speaks. I regularly read The Black Panther, along with Ramparts, a colorful radical left monthly magazine. After witnessing the nearby Columbia University student take-over, I turned my attention to Panther rallies.

The rallies were exciting, and I was intrigued by the Panthers’ message of community self-reliance. I liked their idea of standing up to the powerful. I’ll admit that the black leather jackets impressed me. A march in support of the Panther 21 brought me to the Women’s House of Detention in Queens. After the rally, we entered a subway station to head back to Manhattan. Several dozen young people, Black and white, jumped over the turn styles. A train arrived and we tore up the advertisements posted on the sidewalls. It was total mayhem. The doors closed and the lights went out. We expected the police to arrive any minute. After a while, the train pulled out of the station as if nothing special had transpired, and we were on our way.

One day, on my way home on the commuter train, I fell asleep and I had a dream. Upon waking, I exited the train, and I walked the mile-long hill between the station and our house. At one point the road passes under the Saw Mill River Parkway. I felt scared, as I often did walk to our house. But then, the contents of my dream returned: Black Panthers were coming to the rescue, freeing me from my school tormentors. After marching through town (in my dream), they torched the houses. I felt a sense of relief unlike any I had previously felt.

A year or so later, Panther leaders came to speak at my high school. This was an exciting event for me, a validation of the proudly worn Panther protest pins that graced my denim jacket, and for once, I felt less isolated. After the talk, I introduced myself to one of the speakers, a national leader. I told him how important the group was to me and how much I resonated with their message. He nodded approvingly. I then told him about my dream and obliquely asked whether they might “help out.” He rolled his eyes and was careful not to nod in agreement. While I surely sounded like a cocky (in fact desperate) white teenager, Black Panthers I met during those years were warm and welcomed me as a guest. The experience taught me that despite the hostility I faced in the suburbs, my skin color offered me a tremendous level of privilege and protection from the kind of violence that Black people in America faced every day. I became committed to learning how to be a better ally, irrespective of whether anything came in return.

At the beginning of high school, I began to realize that my ideals were regularly in conflict with my emotions and fears. I recall one Saturday morning in 1970 when I got on the wrong uptown train in Manhattan. I exited at 116 Street, climbed the stairs to the street level only to realize that I was further East, on Lenox Avenue, Harlem, rather than Broadway, Morningside Heights. As I looked around me, the familiar sights of Columbia University were not to be found. Instead, I saw broken down brownstones and a mass of African American faces. I felt a wave of panic and I raced across the street and into the downtown subway entrance.

As my fear subsided, I felt shocked by what I had just done. What had clouded my mind was straight up, irrational fear, I imagined that because I was a white man walking in a predominantly Black neighborhood, local-residents would want to harm me. My emotional reaction reflected a long historical stereotype portraying Black men as dangerous to white people. That experience led me to pay better attention to the negative ideas that flashed across my mind. What I noticed about myself is that racism was not the inevitable, supernatural force it seemed to be, but a carefully nurtured ideology that I had imbibed, despite my family’s liberal politics. While I had little control over thoughts and images, I could choose to act more consistently.

10. Reflections upon a constantly evolving point in time

In Westchester County, our family lived in a racially exclusionary, largely white Christian area. This was a time of transition for Northern Westchester County, as greater numbers of Jews began to move in. We arrived on the cusp of a new era for Jews, but not one for Blacks. I sought to refuse to assimilate my speech, dress, and interests to the new suburban folkways and, without really understanding why, fought back against attempts to squelch my Jewish distinctiveness. My physically small size, artistic tendencies, and loyalties to the City heightened my visibility and opened me to become a ground on which the tensions of that transitional period could be played out. My brother, two years younger, experienced little of this.

In high school, I identified as an outsider in the way I dressed and spoke, and I became increasingly politically outspoken. During spring of my freshman year, my friendship circles shifted towards politically active seniors; their company lessened the degree to which I was targeted. I certainly tried the patience of high school teachers, as they viewed my torn jeans, leather patches, Black Panther buttons, long hair, hand-woven beaded headband, and political rhetoric. When teachers baited me in class, I was more than agreeable to argue back. One of my history classes became a daily two-person debate. I was content being who I was, Jewish, white, a musician, and politically engaged. As insecure and frightened as I remained from the violence of my first three and a half years in Chappaqua, I wasn’t trying to transgress. I was merely doggedly insisting on being myself.

I tried in the best way I knew as a teen, through my writing, speaking, and social relations, to imagine a seemingly impossible world where the institutional terms of race would change, and where my identity as a Jew did not require assimilating into Christian America. As john a. powell observes: “… the history of whiteness has been overwhelmingly concerned with providing a space where exclusion, exploitation, conquest, and violence could be rationalized and normalized.” I wanted no part of this. Only later, in college, did I begin to understand the depth and breadth of the challenge. I sought to understand how I could take responsibility for the privileges I was accorded for my white skin, a theme that has subsequently remained central to my work in the world, while affirming my Jewishness. I felt the dynamics most acutely while taking Afro-American studies courses in college. While warmly welcomed (I was often the only white or Jewish student in class), I had to learn how to listen better and await my turn to speak.

By the end of my college years, fissures between Blacks and Jews had steadily grown. Some Jews felt threatened by the increasing economic and social space sought by Blacks in arenas like university enrollment. Societal forces pitted Blacks and Jews against one another, re-stoking the fears about security that were felt during my grandparents’ generation. Threading the needle between our two peoples’ mutual needs remains a challenge in a society where Jews have more power but continue to feel but provisionally secure, while the lives of people of color remain under threat.

My life has subsequently taken many twists and turns. I have juggled multiple careers as a Reconstructionist rabbi, Social Worker, educator about male violence against women, musician, writer, and college professor. I found my place within American culture, a fourth generation Jewish American, thanks in part to Black America. My parents and, to some degree, my grandparents initiated this relationship, first in Northridge and at Golden’s Bridge. I have had the privilege of being welcomed within the world of jazz, where I view myself as a guest. I have sought to walk the path my forebears blazed on my behalf, at times struggling with some of their – and my – choices. I would not be the person I have become without the good and the bad, the joys and the pains presented within the social locations I have inhabited

The essential question for Jews in 21st century America is two-fold: balancing distinctiveness with assimilation and learning to responsibly wield more power than Jews have ever held, within a society that maintains a persistent color line. Israel, which had been a source of identity and unity for my parents’ generation, has increasingly become a flash point between younger and older Jews, between the political left and right, and between Blacks and Jews. My fraught personal experience of the suburbs taught me to never cease to believe that security is ephemeral. My dad learned in 1942 Kentucky that a person can find their moral center when presented with unexpected decisions, and risking one’s safety. True strength can only be found in acknowledging privilege and power, taking risks, and seeking common cause with those who are politically vulnerable.

Image 12: My parents in 2012, visiting the site of the landing of American forces at Normandy

I continue to believe, like john a. powell, that the key to transforming the racial hierarchy that undergirds our social institutions is a recognition of our fundamental interconnectedness. American whiteness is built on the myth that we are all on our own, operating within a fictional level playing field. Social isolation is dangerous, personally and collectively. Disconnection serves to perpetuate oppression, moving us to use one another for our partisan advantage. This is not a Pollyanna wish for us to join hands while reaping the benefits and stigmas of the social order. I have felt the most capable of engaging these issues in my capacity as a college-level educator. The challenge I have taken on is to facilitate classroom conversations about race within and between races. While this dialog is limited in scope and of mixed success, it gives me hope. As john a. powell instructs: “To embrace our commonality in an increasingly diverse public space will require new selves, who are citizens in the true sense of the term: individual, interconnected, and inclusive in ways that reflect the highest aspirations of our nation and our species….”

As a Jew, the challenge I affirm is to simultaneously join in vibrant non-insular Jewish community while in solidarity and connection with communities of color. Our lives are not our own; they are embedded within the generations. Our task is to learn from our collective past with a level of discernment that was unavailable to our ancestors.

john a. powell quotations are from Racing to Justice: Transforming Our Conceptions of Self and Other to Build an Inclusive Society (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015)