It’s a dry, summer night at La Luz de Jesus Gallery in Central Los Angeles, where a crowd has gathered for the opening of In Memory of Water, an exhibition by Aotearoa-born, Las Vegas-based artist Matthew Couper.

Couper’s paintings echo the aridity of the locale.

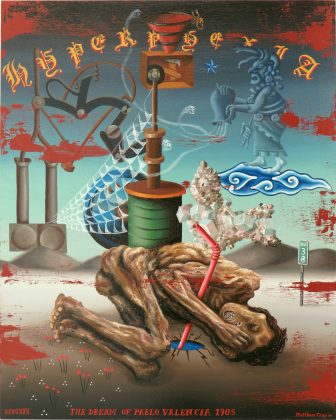

Matthew Couper, Dream of Pablo Valencia, 2019, oil on panel, 16 x 20 in.

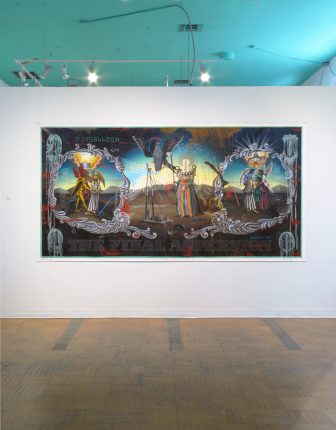

The Dream of Pablo Valencia (2019) shows a man experiencing hyperpyrexia—his organs boil for lack of water. Zanjero Decisions (2016) portrays a debate between angels and demons over water delivery mechanisms—taps or bottles? The Final Aspersion (2018), which resembles a 10-foot long, American dollar, shows a Polynesian chief mourner figure terrorizing a village—a reminder of their shared doom.

The work is about desertification—the transformation of our ecosystem into a waterless abyss.

“There’s no new water,” says Couper. “All the water we’re drinking now is recycled. They’re shipping water overseas to make money. When you take water out of an ecosystem and don’t replace it, you end up with desert everywhere.”

Couper considers his paintings warnings.

“I’m using local stories to talk about global issues,” he says. “I painted Lake Mead emptied out, basically returning it to what it was before the [Hoover] dam was built. It’s showing it returned to nature, but it’s also showing that the water is gone. It’s not a positive thing. If Lake Mead goes, there’s no water for Colorado, Arizona, Southern California. I still think art is one of those visual storytelling structures that might peak people’s interest from just the imagery alone. Someone might see this and look more into the idea of water usage.”

The week Couper’s show closes, Uchronia, an exhibition of new work by New York-based painter Inka Essenhigh, opens across the country at Kavi Gupta gallery in Chicago, where it has rained every day for weeks.

The verdant surroundings are echoed in Essenhigh’s paintings, which are set in a distant, hypothetical, future era in which humanity has solved its toxic relationship with nature.

Inka Essenhigh, New Jersey 2600 CE, 2019, Enamel on canvas, 35.5 × 80 in.

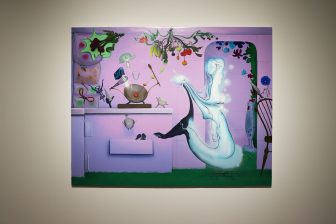

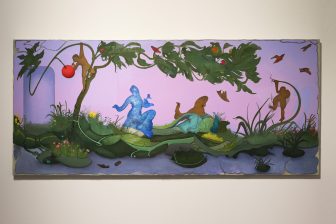

New Jersey 2600 C.E. (2019) shows a lush, biomorphic cityscape in which glowing nanny drones protect playful children a-frolic in a field. Living room 2600 C.E. (2019) shows a home where plants have replaced furniture, and a child sucks juice from a dangling, interior fruit tree. Kitchen 2623 C.E. (2019) shows a translucent chef in a grass-covered scullery, aided by autonomous implements that pick vegetables from ceiling plants.

The work is unabashedly aspirational—pictures of the paradise our progeny could inherit if we get our shit together.

“We are out of balance with the world,” says Essenhigh. “I wanted these new paintings to have an effect. Objects have an effect on you. Colors have an effect on you. It’s subtle, it’s the weak force, but with all that power why not go ahead and use it for something positive?”

Inka Essenhigh, Kitchen 2623 CE, 2018, Enamel on canvas, 60 × 72 in.

Essenhigh considers her paintings questions.

“They ask, ‘What do you want?’” she says. “Do you want people to no longer reproduce? Do you want the buildings to all fall in on themselves? To not have culture anymore? Do you want to live in separate tribes? I painted this world just as an opening to a conversation. Do we want enlightenment? Do we want to just love each other? Well then start thinking about it.”

Essenhigh’s rendering of the future is almost unbelievably optimistic compared to Couper’s depiction of the present. Both visions are striking. Couper’s mastery of surface, color and composition, and Essenhigh’s virtuosity with enamel paint make each body of work undeniably compelling. That these two preeminent contemporary painters chose to use figuration to address humanity’s relationship with nature at a time when contemporary trends lean much more towards spectacle, abstraction, and identity-based work is punk rock, in a fight-bullshit kind of way.

Yet critical reception of both bodies of work is off base. Reviewers seem set on the notion that both Couper and Essenhigh are Surrealists.

In Couper’s case, the label evidently stems from his desert landscapes and grotesque figures, which must remind critics of Salvador Dali. It’s noteworthy, however, that Surrealism has no defined visual component. As André Breton’s 1924 Surrealist Manifesto states, Surrealism is “Pure psychic automatism by means of which one intends to express, either verbally, or in writing, or in any other manner, the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, free of any aesthetic or moral concern.”

Matthew Couper, The Final Aspersion, 2018, oil on unstretched canvas, 64.75 x 121.5 in.

Couper’s use of reason and planning disqualifies him as a Surrealist. (It might also disqualify Dali.) And anyway, Couper isn’t inspired by Dali; he’s inspired by the artists Dali copied.

“I’m interested in artists from post-colonial Mexico,” Couper says. “I’ve adapted a lot of their techniques. I paint on sheets of metal, like tin or aluminum, so I get a very smooth surface. I prime them with a red primer, because back in those days they primed their painting surfaces with a red pigment they got from grinding cochineal beetles. I’ve never figured out why they did that, but I consider it visceral, like how in the Baroque they painted with gold because they saw it as the color of god. I consider cochineal red to be like the blood of god. Spanish colonial times were filled with blood.”

Essenhigh’s Surrealist label comes from the fact that in the past, she actually did court the method.

“Earlier,” she says, “I did use the Surrealistic technique of automatic drawing. In the original enamel paintings in the ‘90s I started with a blank canvas and painted with a very fine brush, and whatever happened happened. While I did this, I told myself stories. It was more of an abstract approach to narrative storytelling. But the Surrealists wanted to shock people, and I never thought I was shocking people. In fact, I think I was always trying to make something pleasurable.”

Essenhigh now prefers the Symbolist label. “If there’s some kind of lineage,” she says, “I feel like I come from Blake, the Pre-Raphaelite Symbolists, fairy painters, on down to Odilon Redon, and Charles Burchfield in America. Then there’s female Symbolists like Katie Sage and Agnes Pelton.”

The reason Essenhigh abandoned automatic drawing, she says, is “because I got tired of meaningless. I wanted to start to control the world we live in, because I can as a painter. I base this on my husband [the artist Steve Mumford]. He went off to war and made drawings of the war. He just drew what he saw, but people wanted the work to be anti-war. They want everybody who makes art that has to do with war to be about how bad war is. After watching this for ten years, I’ve decided there’s no such thing as anti-war art. The most violent films ever made are used for war porn. If you don’t know what that is, before going into battle they will show violent movies to the soldiers, to get ‘em pumped before they go out there. Apocalypse Now is one of their favorites, you know, when they’re coming in over the jungle and just destroying things. There’s no such thing as something that shows you how bad something is so you don’t go there. In fact, that’s what glamorizes it.”

Inka Essenhigh, Living Room, 2018, Enamel on canvas, 36 × 80 in.

The Uchronia series is intended to psyche people up to go out and make a better world.

“Get out there and make that beauty!” Essenhigh says. “I mean, it’s a bit tongue and cheek. But make your beautiful home, make your beautiful garden, live in nature!”

If Essenhigh’s uchronic future is a carrot, Couper’s harrowing present is more of a stick.

“We’re going back to the dark ages,” Couper says. “In the Renaissance, everyone was trying to figure out how things work—how the sun works, how the solar system works. Now we have all this technology, but no one knows how anything works. How does the food get to the casinos? How does the fish get to the casinos? What happens if there’s large, rolling blackouts because we can’t generate enough electricity? The first world doesn’t know how to respond to scarcity. You can’t drink money; you can’t eat money. Those things are part of an elaborate bartering system. At least third world culture has had a chance to adapt—you go and get water and use however much you can carry. The first world thinks in terms of driving, but a two-hour drive could be a 30-hour walk.”

Couper and Essenhigh each note, however, that they’re artists, not scientists, echoing Anton Chekhov’s rule, that artists shouldn’t come up with the answer, they should ask the questions.

How seriously we take their questions, however, might actually determine whether our ecosystem completely devolves into Couper’s hellscape, or manages somehow to transform into Essenhigh’s paradise.

Crucial to that inquiry is that we at least critically acknowledge that neither are being surreal. That label only diverts attention from their all-too-real subject matter: the question of what our various possible futures might look like, and whether we care.