George Yancy interviews Peter McLaren on what he personally learned from Paulo Freire about a liberation-oriented approach to education.

This year, 2021, is the 100th anniversary of Paulo Freire’s birth. My introduction to Freire’s radical and revolutionary work began when I was introduced to his seminal book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. That text alone forced a new vision for how I came to think of education as a site of profound nurturing and reciprocity between students and teachers. In fact, for me, the very idea of the teacher and student relationship had to be rethought outside of a neoliberal framework that stressed marketization, privatization, commodification, consumerism, and a social reality believed to consist of atomic individuals whose sole raison d’être is entrepreneurial, where the aim is to maximize one’s power on the basis of zero-sum logics. Such a form of “education” is ripe to support the status quo through the manufacturing of a false messianism, where those in power attempt, as Freire says, “to save themselves.” Education, on this score, is not designed to trouble the social order, to disrupt complacency, and disturb milquetoast mentalities, but to produce more cogs within a hegemonic cookie-cutter society where homo economicus rules, that is, where human beings ruthlessly and narrowly battle to promote their own self-interests. Such a society is predicated upon those who are deemed “losers” and are left out, discarded. The “winners” take all. There is also the reigning ethos of indifference vis-à-vis the least of these, a society that willfully refuses to see those who suffer, those at the bottom, the subaltern, the stranger, the denied immigrant, the pain and injustice experienced by Black, Indigenous, People of Color, those within the LGBTQI community, and those deemed “monstrous” because of visible impairments. This politically reinforced social reality that encourages violence and xenophobia is consistent with the right-wing nationalistic fervor that we see in Brazil, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Slovenia, and in the US under the neofascist (white nationalist) tendencies of Donald Trump and his political minions who continue to propagate the lie that the 2020 election was rigged and stolen. How does radical education, which is designed to cultivate radical imaginations and critically informed dissent, become sustained and nurtured in the face of dogmatism, misinformation, and the “dis-imagination machine,” as Henry Giroux says? This is where the indispensability of Freire’s thought and action come into play.

Freire understood, through his revolutionary educational work with oppressed peasants and workers in Brazil, that hegemonic and massive inequity creates a “culture of silence.” Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel writes that “The prophet’s word is a scream in the night.” It is Freire’s scream that continues to speak to us about how our “ontological vocation is to be more fully human.” For Freire, it is what he calls the banking system of education, one consistent with dis-imagination, that installs fear, cowardice, aversion to resistance, and that suppresses a critically engaged demos. The banking system of education is designed hierarchically to produce passive students, and functionary teachers. It is a system where students are not taught to be active subjects of the learning process, but empty containers, which, for Freire, is “an oppressor tactic” as it creates dependence. As we here in the US find ourselves on the precipice of undoing our fragile experimental democracy and falling into a draconian dystopic world of indifferent power elites, it is important that we celebrate the work of Freire. Like Howard Zinn, Freire understood that “Education can, and should be dangerous.” It is dangerous, though, to those who would prefer we sleep, who would prefer we not ask questions about climate change, anti-Black racism, misogyny, homophobia and transphobia, anti-immigration, the erasure of multiculturalism, and the banning of critical race theory. Heeding Freire’s voice could mean the difference between life and death, between radical love and radical global extinction. Freire is clear, “The dialogical theory of action does not involve a Subject, who dominates by virtue of conquest, and a dominated object. Instead, there are Subjects who meet to name the world in order to transform it.” Let us, then, transform our world.

With this, it is with great appreciation that I have been given the honor of conducting this broad and engaging interview with the prominent scholar, activist, and public intellectual Peter McLaren. Peter discusses with deep insight not only the work of Paulo Freire, but provides us with a genealogy of his own critical thinking and emancipatory praxis. This critically engaged space speaks to the importance of critical reflection and courageous speech, especially as we continue to live within the context of an American ideology of obscurantism, one that rejects critical thinking, one that avoids processes of nurturing challenging questions, one that fears ethical daring, and one that refuses to engage in deep political and epistemological self-interrogation. Yet, a critical pedagogy—one infused with deep probing of and outrage against systemic forms of violence, hatred, and oppression—is what is necessary if we are to create sites of deep reflective praxes that resist global forms of suffering, which includes the earth itself. What is also necessary, which I see as inextricably linked to critical pedagogy, is a radical form of love, a form of love that can see beyond the barriers that have rendered us strangers to one another. It is a form of love that is fueled by a vision of mutual healing, global solidarity, and collective liberation. Peter embodies this call for radical love and takes us through an engaging process that imbricates autobiography, intellectual history, and the spirited and revolutionary work of Paulo Freire. For those of us who attempt to speak out against various manifestations of evil, to name them, and to call them out, Peter’s voice moves us and encourages us to keep alive a radical spirit of loving transformation.

Peter McLaren is Distinguished Professor in Critical Studies at the Donna Ford Attallah College of Educational Studies, Chapman University. He is also Emeritus Professor of Urban Education at UCLA School of Education & Information Studies. From 2015-2020, McLaren taught as Chair Professor at the Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China. He is the Co-Director of the Paulo Freire Democratic Project where he serves as International Ambassador for Global Ethics and Social Justice. Professor McLaren is co-founder of Instituto McLaren de Pedagogía Crítica in Ensenada, Mexico. He is the author and editor of over 45 books. His writings have been translated in 25 languages.

George Yancy: Peter, as someone who knew Paulo Freire, and who has grappled with his work for a significant period of your life, I would like to ask you a series of questions related to his work that I think that you are uniquely qualified to address. Indeed, in our contemporary moment of systemic oppression of various sorts, vast forms of dehumanization, marginalization, and violence, I think that Freire’s voice is indispensable and vital as we rethink a robust and loving conception of humanity.

My teaching is deeply informed by critical pedagogy, especially as articulated by Paulo Freire. As I introduce my students to philosophy, I make important connections between philosophy as a critically engaged project that disturbs the status quo and Freire’s critique of the banking system of education, which is designed to keep people complacent, passive, and ignorant of their oppression. For me, philosophy is not simply an abstract love of wisdom and conceptual analysis, but a form of love and wisdom that extends beyond the halls of academia and touches the lives of embodied people who too often live within contexts of deep pain and suffering. In one of your important books, Life in Schools, you write, “Critical pedagogy resonates with the sensibility of the Hebrew phrase of tikkun olam, which means ‘to heal, repair, and transform the world.’ It provides historical, cultural, political, and ethical direction for those in education who still dare to hope.” Given the venue of our interview, say more about how you understand critical pedagogy as an approach to education that heals the world.

Peter McLaren: I very much agree with you George—unequivocally in fact—that Freire’s work is indispensable today. Given the rise of identitarian ideology, ethno-nationalism grounded in ideas of racial purity and support for the racial state (but where the term race is now hidden under the cloak of “cultural differences”), and the instantiations of White supremacy and anti-Semitism that are furiously populating the ideology of Trump’s base in the current U.S. context, we need Freire more than ever. Support for democracy is now evanescent among the current Republican party. In fact, White victimhood, misology, and hatred by Whites of non-White immigrants and people of color in general, has gone analogue. Professors drawn to Freire’s work, foot-weary from battling truth-obliterating anti-rationalism, are being pressured to tone down their anti-fascist efficacy because it might create divisiveness on college campuses.

Right-wing extremism—claiming Black Lives Matter to be a terrorist organization or characterizing Critical Race Theory as a communist conspiracy designed to take over the United States, for instance—has become so rampant that more authoritarian populists, worse than Trump, are poised to emerge from the sidelines and make emotional connections with the aggrieved low-wage and middle-class base and deliberately call for bloodshed. The calumny against professors inspired by Freire, who challenge right-wing extremist hate on campus, is outrageous as university administrators push for progressive and left professors to tone down, as I just said, their anti-fascist efficacy because of fear of exacerbating divisiveness on campus. However, these perpetrators of hate need to be challenged by a pedagogy of everyday life that is Freire’s. Dialogue is one way to do this. And we must find more creative ways of engaging in the culture wars on campuses. Every pedagogy needs to be self-critical, otherwise, in time it will degenerate into a self-righteous hypocrisy, and I am sure Freire would agree that we need to find more creative ways to fight the hate.

Yancy: And I’m sure that Freire would have been against a kind of self-apotheosis and where his work would be deemed beyond critical discussion.

McLaren: Yes, Freirean pedagogy should not be treated as a religious text and certainly not worshipped but it needs to inform the basis of our praxis as educators. Freire came to understand that oppressed learners had internalized profoundly negative images of themselves (images that Freire identified as created and imposed by the oppressor) and felt powerless to make changes in their lives and become active agents in history. Freire created the conditions for learners to examine the limits and possibilities of the existential situations that emerged from the experiences of the learners—experiences that were often traumatic and life-denying. Critical consciousness demanded a rejection of passivity and encouraged the practice of dialogue wherein learners were able to identify contradictions in their lived experiences and were able to reach new levels of awareness of being an “object” in a world where only “subjects” have the means to determine the direction of their lives; where you made a choice to create history rather than being a casualty of history. And yes, Freire’s critique of “banking education” (depositing funds of knowledge into the brainpans of students) is one of his central contributions. North American students come to appreciate this critique more quickly than in other countries in which I have taught classes. For instance, this was an extremely difficult concept for graduate students who I have been teaching in China over recent years to appreciate. Students initially asked me why I was wasting class time inviting students to share their life experiences, claiming that I was the expert and they wanted to put to memory my ideas which I was encouraged to list on a PowerPoint presentation. Fortunately, they began to appreciate Freire’s critique once sufficient trust prevailed among us. And eventually they started reading Pedagogy of the Oppressed in Mandarin (That I had written the introduction to the Chinese version to this text also helped win me some credibility).

Freirean education is not about discovering the truth of the world through theoretical study and then engaging in a step-by-step application of our knowledge to the world, but rather engaging the material world critically in ways that enable an understanding of the world that seizes the will of the learner. Those whom Freire referred to as the oppressed see a world that they believe has already been written and view themselves as having been written out of this world. Freirean critical consciousness is a type of protagonistic knowing that occurs by “re-cognizing” the world as an arena of struggle and seeking the means to overcome the privileging hierarchies that constitute it—effectively re-writing that world by being in and with the world, that is, moving outside the fatalism that pervades the technocratic logic of capitalist modernity which traps so many of the oppressed as victims of history. For Freire, becoming critically conscious is the path to humanization, to our ontological vocation of becoming more fully human, it is a path that creates the conditions of possibility of becoming agents capable of making history rather than remaining bearers of history’s inevitability. This is what forms the basis of a Freirean reading of the word and the world—a reading that is co-intentional (the student as educator and the educator as student), protagonistic, and dialogical. Freire understands that protagonistic or revolutionary agents are not born, they are dialectically produced by circumstances. To revolutionize society, it is necessary to revolutionize thinking. Yet at the same time to revolutionize thinking, it is necessary to revolutionize society. All human development (including thought and speech), for Freire, is social activity and this has its roots in collective labor. It is important to understand that for Freire, process and the outcome become one—which Freire refers to as critical consciousness.

Freire provides us with a way of challenging learners with words and concepts that emerge from their own lived histories. Freire’s ideas have been adapted in the United States among practitioners of what is known as critical pedagogy. Critical pedagogy has made some inroads in graduate schools of education to the extent, at least, that students will graduate with some rudimentary understanding of Freire’s work. However, high school teachers who use Freire can be more closely monitored by parents and administrators where discussion of race, class, gender and LBGTQ issues have become increasingly anathema to certain pro-Trump, QAnon, and cult-driven constituencies. Too often it’s the case that colleges of education offer very few courses or programs designed around Freire’s work or critical pedagogy. Here, concepts from the social sciences—feminist theory, critical theory, critical race theory, Marxist economics, African American Studies, liberation theology, and so on—potentially serve as dialectical relays through which students can “read the world” against the act of “reading the word.” What I mean here is the process of reading one’s lived experiences, as those experiences are reflected in or refracted through various critical theories that offer explanatory frameworks that can help students make sense of their own experiences. The idea is to create conditions of critical consciousness or critical self-reflexivity among students. You can’t teach anyone anything by injecting your ideas into the veins of their consciousness, you can only create the conditions for people to learn. The idea is to provide resources, including opportunities for dialectical reasoning, to help students understand how various ideologies drive social life, to help students discern how systems of intelligibility or systems of mediation within the wider society (nature, the economic system, the state, the social system, cultural system, jurisprudence, schools, religion, etc.) are mutually constitutive with the formation of the self.

Yancy: So, for Freire, we are not talking about a unidirectional transformation or an enclosed Cartesian process of epistemological reflection, which, I must say, bespeaks an atomistic, neo-liberal conceptualization of the self.

McLaren: That’s right. When we talk about liberation, we are referring to self-and-social transformation and not just self-transformation; that is, we are referring to a dialectical relationship. We need not refer to the self and social relations as though they were mutually exclusive categories, antiseptically distant from each other. They are not steel cast terms but rather bleed into each other. Again, it’s a dialectical relationship. It is at this point that we arrive at the notion of praxis, the bringing together of theory and practice. Of course, we demonstrate that praxis begins with personal agency in and on the world. We begin, in other words, with practice and then enter into dialogue with others reflecting on our practice. This reflection on our practice, then informs subsequent practice — and we call this process or mode of experiential learning revolutionary praxis, or self-reflective purposeful behavior, that is, exploring with others the relevance of philosophical ideas to the fault lines of everyday life and the necessity to transcend them when they foster oppressive forms of domination. So yes, I felt that the term “tikkun olam” captured the spirit of Freire’s work. I know very little about the mystical writings of the Lurianic kabbalah, but I have read that historically it has referred to a specific cosmological account where Adam was exercised to restore God’s divine light that had been shattered and disbursed during the act of creation. Acts of repair were meant to imply religious acts, but I am using the concept in a more contemporary sense, and in my use it can be seen as synonymous with the popular concept of social justice and God as the idea of unconditional justice. By repair I am referring to creating conditions of possibility for producing social relations of solace and hope to restive and aggrieved populations who are suffering under the forces and relations of domination and oppression—one of the lodestones of Freire’s work. The term also resonates with Freire’s profound contributions to liberation theology.

Yancy: I would like to explicitly return to Freire’s work in relationship to liberation theology, but I want to ask a question about his status as a public intellectual. I see the public intellectual as one who speaks with courageous speech, who attempts to identify with those who are treated as the least of these, where the subaltern and the oppressed are not treated as “objects” but as subjects. In this sense, the public intellectual attempts to create a space of shared relationality of mutual concern and a collective sense of fighting against those forces that are dehumanizing. The public intellectual, in short, relates to the “funk of life,” as Cornel West would say. How do you understand the role of the public intellectual, especially within a context where many in America seem to be comfortable not knowing the existential magnitude of human pain and suffering or the suffering of the earth for that matter?

McLaren: Cornel West wrote the Preface to my first book about Freire and I was equally grateful that bell hooks and Henry Giroux—already considered public intellectuals—agreed to contribute. You can’t ask for stronger, more committed public intellectuals than these three luminaries. And Freire’s work has made him the consummate public intellectual for reasons you describe. Giroux has written mightily on the concept of teachers as public intellectuals and one of his first explorations into this was his book, Teachers as Intellectuals where he made a distinction between “hegemonic intellectuals” and “critical intellectuals,” which was inspired by Antonio Gramsci’s storied work on “organic intellectuals.” Do we want our teaching to be reproductive of the status quo in which so many suffer? Or do we want to challenge dominative forms of oppression? This choice posed by public intellectuals such as West, hooks, Giroux, and Freire provided for many of us a powerful rationale for doing liberatory work in the public sphere. Now the criticism was that public intellectuals were undermining tradition and historical memory and the narrative and symbolic glue that supposedly held the country together and made us proud in being Americans and defenders of the American Dream. There was also the charge that we were being anti-patriotic and hateful of American institutions—well, you can imagine the criticisms. Many public intellectuals were denounced for being “critical theorists” in the tradition of the Frankfurt School (who were all Jewish intellectuals and perceived as communists and subversive of democracy) and were followers of Herbert Marcuse who was Angela Davis’s mentor during her graduate studies—mentor to a Black Panther, what could be worse during those days? But clearly it is important that we relate our work as public intellectuals to contemporary crises of humanity and make concerted attempts to address the public on such issues in terms that would be more accessible than those used in the academy without diluting the main ideas.

Becoming a media personality is not a litmus test for being a public intellectual by any means. Freire’s role as a public intellectual was carved from his brilliant writings, from his activism, from his willingness to travel the world and engage with other thinkers in deliberative, critical dialogue. It wasn’t easy to find the means for public intellectuals to get their ideas across to wide audiences in those days except through publishing a popular book. And you risked offending your institution—in today’s terms, being “cancelled”—even if you maintained that your ideas did not represent your institution. The term “radical professor” became part of the mainstream media lexicon and public intellectuals were often censured. Sound bite media formats meant that the ideas of public intellectuals could not be sufficiently adumbrated in a manner accessible to the public and occasionally public intellectuals were deceptively framed to appear like idiots. I was certainly not recognized as a public intellectual, but I did agree to speak out in the media on the few occasions I was invited to do so. I appeared on a talk show once where during the break the producer encouraged me to turn over a coffee table in anger. I refused and my appearance was cut out of the show, and it was never aired because I refused to accept the way I was being characterized in the “teaser” to the show. It was more than “awkward.” During my doctoral studies I was fortunate to enroll in a class taught by Michel Foucault who was visiting the University of Toronto at the time and who, during a trip to bookstores across the city, spoke to me about the idea of dangerous knowledge and from his lectures I came to realize much more deeply that certain intellectuals going public were too threatening to the establishment media. Think of the case of Noam Chomsky, a public intellectual I greatly admire. You don’t often see him interviewed in the mainstream press even today, although for decades he has been acknowledged as one of the world’s greatest intellectuals, someone who can put complex issues into accessible terminology and someone who wants to do more than understand political history, but to act upon history, to impact the world in a way that promotes human freedom. Again, what he offers is dangerous knowledge, knowledge dangerous to the public. There is less trust in academic institutions today and in the public square. Distrust—in science for example—is one reason why so many people see an argument as equivalent to having an opinion, so you can find the most outrageous ideas expressed in today’s media by those who retreat into their own platforms on social media where people dance to the same opinionated beat with no desire to do otherwise. For the last few years, I have heard from many right-wing students, and some on the left, usually undergraduates: “Ok professor that’s your opinion on Freire’s work, and I have a different opinion.” But they present no cogent evidence for holding onto their opinions. People have lost the ability to adjudicate arguments and we unceremoniously reject them in favor of opinions to the extent that people cling to their viewpoints even in the face of objective evidence to the contrary. To them, truth is all about emotional appeal and having their ideas affirmed which are most comfortable to them. Freirean dialogue could break this impasse precisely because, as you so clearly affirm, of the ability of his pedagogy to create a “shared relationality of mutual concern and a collective sense of fighting against those forces that are dehumanizing.” That’s precisely why Freire, Chomsky, hooks, Giroux, and others are considered authentic public intellectuals and it distinguishes them from today’s so-called thought leaders, which is one reason Freire and authentic public intellectuals are needed more than ever at a time when the country is divided in more and deeper ways than it has been for generations.

Yancy: I am envious in the best possible way that you not only took a course with Foucault, but that you met and knew Paulo Freire personally. Share with us what it was like when you first met him. What was it about this man that emboldened your own sense of political praxis and intellectual courage? And how did his influence broaden your philosophical, political, and pedagogical vision?

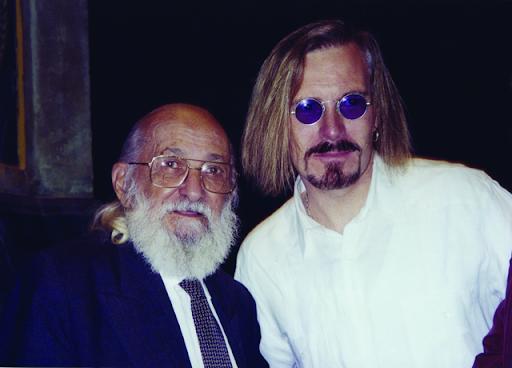

McLaren: I first heard Freire’s name spoken in the halls of the Department of Adult Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, part of the University of Toronto in 1979, the year I began my doctoral studies. Apparently, he visited the Institute during my time there as a doctoral student and I missed him. But I first met him in person at a conference in 1985 in Chicago where he was the featured speaker, with attendees spilling over into the aisles of the auditorium eager to hear him. Henry Giroux and one of Freire’s closest North American colleagues, who had immigrated from Cabo or Cape Verde, Africa, Donaldo Macedo, introduced me to Freire at the conference. Macedo, a linguistics professor, was one of the world’s leading exponents of Freire’s works. What shocked me was that during my conversation with Freire, he knew some of my work. This certainly bolstered my confidence in my research. Paulo would eventually write prefaces for two of my books. When in his preface to my first major work, Critical Pedagogy and Predatory Culture, he talked about me as his “intellectual cousin,” I understood why so many referred to Freire’s humility and generosity of spirit. When Paulo, Donaldo, and I came together, they would both tease me with delightful impertinence. Once during a meal at a Portuguese restaurant in Boston, which had a live band, Donaldo and Paulo asked the band to announce that it was my birthday and play “happy birthday” for me—about five or six times during our meal. Of course, it wasn’t my birthday. Freire had a wonderful sense of humor and was often playful.

There was competition among North American educators around their relationship to Freire and I realized some academics were downplaying my work privately to Freire, trying to undermine our relationship but it had no effect on him. Freire had a sense of integrity to him that was consistent and profound. Freire was careful during talks to recognize publicly those in the audience whom he knew and was often worried about hurting someone’s feelings for overlooking them in the audience. Freire invited me to his home in Sao Paulo and attended my lecture at the university and helped to translate some of my concepts into Portuguese—even though his English was not very strong. Paulo participated in a conference which became a book, Mentoring the Mentor, with bell hooks, Antonia Darder and Giroux in attendance, and many other well-respected scholars. And with great humility, he invited all those in attendance to challenge or clarify concepts he had developed in his work. Some of the best Freirean scholars—such as University of Malta’s Peter Mayo—did not have the opportunity to meet Freire in person, so I consider myself fortunate to have been able to spend time with him.

Freire has been a powerful inspiration throughout my life and my scholarship on him led to numerous invitations to Brazil where I was especially interested in Afro-Brazilian religion, Umbanda in particular. Afro-Brazilian members of the Workers’ Party made it possible for me to witness Umbanda rituals that normally excluded outsiders. The Freirean community is now vast. Freire’s work is the dialogical glue that enjoins so many of us to venture on the path to freedom. Given the contextual specificity that gave rise to Freire’s work in the countryside and in urban barrios and favelas, his work was not easily generalized across and applicable to many educational settings without falling prey to misunderstanding and running afoul of political authorities. His work was always vulnerable to political domestication, as when liberal teachers in the US would often reduce his work to the teacher sitting in a circle in a classroom and having conversations with students over current events or what they did over the weekend. Not that there is anything intrinsically wrong with that, but critical pedagogy doesn’t stop there. Freire was reluctant to have his ideas “exported” across international borders where they would lose both their nuance and specificity; hence he always encouraged educators to “reinvent” his work rather than simply “transplant” it in geographical and geopolitical contexts outside of Brazil. His work would therefore need to find trusted educators who could “translate” and adapt his ideas to various national, regional, and local contexts both inside and outside of his native country. One example of this was during the Nicaragua’s National Literacy Crusade where elements of his pedagogical and methodological approach adapted to the specific circumstances in Nicaragua. Reacting to criticism of the campaign as being too partisan politically, Freire was known to respond that such a campaign was “not a pedagogical program with political implications, but rather, it is a political project with pedagogical implications.”

For Freire, learning involves a dialectical reading of the word and the world, of learning to recognize opportunities for changing the world that he referred to as “untested feasibilities.” The act of knowing, for Freire, does not move in discreet methodological steps—from an epistemological shift in consciousness brought about by a teacher skilled in the Socratic method, followed by an ontological shift in behavior by the student signaling a different way of being in the world and relating to others—since for him this leads to a type of bifurcated Cartesian knowledge. It simply repeats the anti-humanism of Western enlightenment learning that is grounded in a Cartesian dualism separating mind and body, while also ignoring the contextual specificity surrounding the act of knowing and its concrete materiality. This concrete materiality of our lives that so fascinated Freire refers to the lived experiences of the learner, experiences that are bodied forth, that are enfleshed, where learning occurs not solely in the “mind” but in the bone and sinew of everyday joy and hardship, in everyday spaces of strife and struggle in the home, the school, and the streets of the favelas, in the transformative praxis of everyday life. Here, achieving critical consciousness is not a necessary precondition for self and social transformation (i.e., you need not read the great philosophers before you are ready to undertake political action) but rather an outcome of acting in and on the world critically, with an important prerequisite to this praxis being a love for the world and humanity (in this sense ethics, for Freire, precedes epistemology). Freire helped me to understand the importance of acting in and on the world out of a love for the world and reflecting on our actions in an attempt to produce a deeper, more critical change in our society. His approach has recently been compared to the “non-methodical method” of the French pedagogue Joseph Jacotot (1770–1840), creator of universal teaching or panecastic philosophy, made famous by Jacques Rancière and his important stress on aesthetics. However, some critics of Freire view his concept of praxis as too reliant on an assumption of society as dehumanized and people dichotomized as oppressor and oppressed, but I don’t agree with this assessment of his work.

Yancy: I would like to return to liberation theology. When I think about Paulo Freire’s liberationist sensibilities, I think of liberation theology. What would you say are some of the shared conceptual and praxis-oriented similarities between his work and the emphasis upon Christology as a process of kenosis (or emptying) and radical forms of metanoia (or a transformative change of mind/heart)?

McLaren: A high regard for self-correction and kenosis in Freire’s pedagogy appear to be implicit in his work but Freire did not detail his theological conceptions of Christ. His impact on liberation theology went in different directions which were more in keeping with social science. This made Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed the third most cited work in the world in the field of social sciences and the first in the world in education, prompting Freire to become both a target and a prophet in his own country. Freire was clearly anticlerical—who wouldn’t be growing up in the face of the dogmatism and frequent hypocrisy practiced by the Church—and was opposed to the formalism and imposed neutrality of the Church, which allowed the Church to appear to be serving the oppressed while actually supporting the power elite. Accepting Church dogma uncritically was not unlike a banking approach to educating one’s faith—but when you emphasize proper doctrine over praxis, you are, in effect, emptying conscientization of its dialectical content and affirming what is essentially a static, necrophilic (death-loving) consciousness, rather than creating a biophilic (life-loving) consciousness. It is the former which de facto constitutes “an uncritical adherence to the ruling class.”

Freire is known for famously calling for a type of class suicide in which the bourgeoisie willingly take on a new apprenticeship of dying to their own class interests. He likened this to experiencing one’s own Easter moment through a willing transcendence of the heart and mind. But this was not an endorsement of mysticism or other-worldliness—it was political to the core. Freire was uncompromising in his view that dominant class interests must be replaced by the interests of the suffering poor if Christians are to experience their “death” as an oppressed class and to be born again to liberation. Otherwise, Catholics will be ensepulchered within a Church “which forbids itself the Easter which it preaches.” This sentiment is reflected in Freire’s famous words:

“I cannot permit myself to be a mere spectator. On the contrary, I must demand my place in the process of change. So, the dramatic tension between the past and the future, death and life, being and non-being, is no longer a kind of dead-end for me; I can see it for what it really is: a permanent challenge to which I must respond. And my response can be none other than my historical praxis – in other words, revolutionary praxis.”

Peruvian priest, Gustavo Gutierrez, considered one of the founders of liberation theology, invited Freire to work on some components related to liberation theology and Freire began to analyze the distinct differences among what he called the traditional church, the modern church, and the prophetic church and strongly advocated the creation of a prophetic church—no wonder Cornel West was such an admirer of Freire! As a proponent of the prophetic church, Freire made considerable contributions to liberation theology, a movement that continues to this day and whose proponents risk their lives for the sake of the well-being of the poor, the exploited, and those who are the targets of brutal military regimes and government repression. True to his principles, Freire refused to exhort others to follow a path of political activism that he, himself, was unwilling to follow. Freire understood only too well that the Catholic Church was neither working for the social and spiritual liberation of oppressed peoples nor was it taking a critical stance toward existing socio-political structures or engaging in an ongoing process of challenging the structures of oppression on behalf of the poor and oppressed. Right-wing Catholics led the Church to be as corrupt as the governments they were purportedly trying to legitimize—and sometimes worse. Nita Freire captures the essence of the prophetic church that Freire envisioned when she describes it as the “one that ‘feels’ with you; one that is in solidarity with you, with all the oppressed in the world, the exploited ones, and ones that are victimized by a capitalist society.”

It was in the prophetic church inspired by liberation theology where one could truly bear witness to faith, solidarity and hope being conjugated with the struggle and risk-taking that is necessary for creating a better world. Personally, George, I have found God on the picket line more times than I have visiting cathedrals. Nita sent me a few years ago a photo of her private audience with Pope Francis whom I understood read Pedagogy of the Oppressed during a time of banishment when some of his fellow Jesuits accused him of not doing enough to challenge the brutality of the Argentine state during the dirty war. While I would not consider Francis to embrace whole cloth the path proposed by liberation theology, he is certainly sympathetic to it and is an admirer of Freire. Just look at how he has incurred the wrath of many conservative Catholics. In the final analysis, the prophetic church is any place where people gather to believe in God, struggle to emancipate the poor, and strive for social change—so it doesn’t have to be Christian specifically. Liberation theology is ecumenical and works throughout and across many faith-based religious traditions. That in itself is profoundly Freirean.

Yancy: The connections that you make here, Peter, are deeply insightful. Speaking of uncritical conservatism, in our contemporary moment, critical race theory is under attack by mostly conservative white people, especially various politicians. There is the deeply problematic assumption that critical race theory is against white people, which, as we know, it isn’t. Critical race theory is aimed at generating critical analyses that critique and attempt to dismantle white supremacy. Critical race theory calls attention to the ways in which white racism has been and continues to be embedded within American institutional life and within the habits (conscious and unconscious) of those who support anti-Black racism. My sense is that attacks against critical race theory are fueled, in part, by those who are invested in the status quo, which entails the maintenance of a revisionist understanding of America’s investment in white supremacy and what that investment meant and continues to mean for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC). Were Paulo Freire alive today, what form would his response take in response to the attempt to silence the critical insights of critical race theory?

McLaren: Decades ago, as a much more orthodox Marxist than I am today, I recall both my admiration for critical race theory but also my criticism of it on some theoretical grounds—mostly for not paying sufficient attention to the strategic centrality of class in our revolutionary struggle. However, Freirean dialogues with Marxist humanists over the years have convinced me that I was misguided in that assessment, especially as I have come to appreciate the magisterial work of Frantz Fanon.

Critical scholars both in today’s fascist United States and Brazil—I don’t believe the term fascist is too strong—have vociferously denounced the legacies of settler colonial societies that from their inception to the present day have been stained by acts of genocidal slavery, democide, ecocide and epistemicide, the historical memories of which too often remain buried in the crevices of history. Freire’s work has been at the forefront in bringing many of these acts to light and I am confident that Freire would support critical race theory, even though his work did not sufficiently address the concept of race, gender, or sexuality. There are, to be sure, George, clear similarities between contemporary attacks on Freire in Brazil, the virulent backlash against critical race theory, and the attacks against Nikole Hannah-Jones’ New York Times 1619 Project, which is a major critique of the centrality of racism and slavery in U.S. history. As a result, state legislators across the country are working hard to pass laws which would gravely circumscribe the ways in which slavery and racism are taught in the United States, effectively prohibiting insights gleaned from critical race theory.

Both Trump and Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil’s current president) continue to wage a war on truth, using a cruel, calculated, artificial logic that has ushered in an era of post-truth politics under the slogan of “fake news.” Freire reveals to us that what is true is not so much syntactical as it is pedagogical because education is about forming minds and cultivating counterhegemonic actions and for that you don’t need blueprints but at the very least you require premises that are warranted. What Freire offers us is both an educated reason, and a general theory of education, a reason tempered by the realities and struggles of his own life: his imprisonment, his work in Guinea Bissau, his work in support of Latin American guerrilla movements, and his work with teachers throughout Latin America and the United States with whom he developed a deep solidarity. What the murder of George Floyd, the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and the global pandemic has brought to the fore in the public arena is a recognition of the obscene disparities between the rich and poor, between White folks and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, between immigrants and the so-called “real” Americans—and the pain and suffering that has ensued over the centuries among these groups. Such issues are, at most, tepidly acknowledged during times of national crisis yet tend to recede back into that dark ether of willful forgetfulness, of historical amnesia, once a crisis has seemingly passed. What critical race theory teaches us is that the legacy of racism and slavery must be examined and reexamined by each generation if democracy and the struggle for freedom is to survive, in order to avoid those “circumstances and relationships that made it possible for a grotesque mediocrity to play a hero’s part” (if I may borrow some words from Marx used to describe the class struggle in France). While we would be hard pressed to expect a full-throated denunciation of the violence that the United States has unleashed into history through the unholy exercise of its sacred claim to be the defender of liberty and the protector of freedom by those ardent proponents of American exceptionalism, we should in no way stand silent while the Trumpists are destroying what remains of American democracy in their campaign against evidence-based truth and in their attempts to sacralize the Big Lie that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump, and to erase the history of slavery by using the law to prevent dialogue around these issues in classrooms. The American academy has been successful in working out ways to quarantine Freire’s work away from social revolution grounded in a philosophy of praxis but that is what we need—a social revolution in our pedagogy that will bring us closer to creating true freedom and justice.

Just when we need Freire the most, attempts are being made now to rebury him along with critical race theory, to shut down all attempts to produce a critical citizenry, to make it a crime to teach the history of slavery or to provide a language of analysis designed to uncover historical events unflattering to the so-called American patriot movement. These are veiled attempts at denigrating pluralism, at promoting white supremacy and fear of immigrants, and advocating for the creation of a white Christian ethno-state. My early visits to Brazil, to São Paulo, Bahia, Porto Alegre, Santa Maria, Rio de Janeiro, Santos, Uberlandia, Santa Cruz do Sul, Cachoeira, and other places, provided me with the opportunity to glimpse a profound intersection of politics, culture and consciousness-raising among people who were struggling for social justice in ways that Freire clearly understood. I learned from Afro-Brazilian members of the Workers Party—great admirers of Freire’s work—about the horrors experienced by the four million slaves forcibly taken from West Africa to Brazil by Portuguese colonizers, beginning in 1538 and continuing until its abolition in 1888. It was necessary to come to the realization that the scourge of racism was not an unintended or unanticipated outgrowth of capitalism, but that capitalism was racialized from the very beginning by virtue of already established systems of racial classification. In many ways we need to think of capitalism as “racial capitalism” in the sense that racism didn’t emerge from capitalism in some linear progression but was co-constitutive with the development of capitalism. Racism is not a by-product of capitalism; it should not be considered epiphenomenal to capitalism. Admittedly, Freire understood the workings of capitalism far better than the practice of racism. Today he would have appreciated competing conceptions of the history of racism and used those to deepen his understanding. Furthermore, I was privileged to discuss the plague of racism and capitalism and many related issues with Freire at his home in Sao Paulo. Ultimately, Freire recognized that history does not make history, people make history. Freire’s humanism is exceptionally relevant to the future that we face. The Trumpists are calling for patriotic education in the spirit of American exceptionalism, as if the country emerged onto the world stage as some ahistorical grand narrative, when, in fact, United States militarism has in too many instances left a saber slash across the cheekbones of history.

The attacks on critical race theory invites an aerosol patriotism born from a studied forgetfulness, a motivated amnesia surrounding the history and origins of the country. It is the type of poltroonish patriotism that could easily be imagined emerging from a Fox News coffee klatch. It’s an alethophobia tinctured by white supremacy and a refusal to reckon with the country’s past crimes against African slaves, indigenous peoples, and non-white immigrants. The mandates surrounding this type of patriotic education enshrines its teaching in a frozen orthodoxy, a dark alchemy, where learners are ensepulchered in an intellectual mausolacracy ruled by dead white men and filled with scripted memories of things long past, such as truth, democracy, courage, commitment, and justice. Furthermore, it’s primed and fitted with an uncanny obligation to pay fealty to political expediency, shopworn dogma, and Trump’s low rent casuistry. It’s a throwback to those cherished “great again” days of Jesse Helms and George Wallace and Jerry Falwell Sr. It brings back for me images of Lee Atwater playing his blues harp while planning more Southern Strategy political maneuvers, and Karl “MC” Rove dancing to a rap song. Speaking of Falwell, it’s hard to forget his fulminations against integration and the Civil Rights Movement from the refurbished bottling plant in Lynchburg, Virginia, that became the infamous Thomas Road Baptist Church where Falwell distributed propaganda pamphlets created by the FBI to discredit Martin Luther King? Is this the America to which we wish to return? What does Liberty University think about that?

While Freire worked as the municipal secretary of education in São Paulo at the end of the 1980s, his work was never officially integrated into Brazil’s educational system. But because Freire’s work is considered by his critics to be synonymous with the Workers Party, his writings have come under the same kinds of ideological attacks in Brazil as those marshalled against critical race theorists in the United States—vigorous and ugly condemnations. That Freire was designated the official patron of Brazilian education in 2012, during the reign of the center-left Workers Party, has been a bone of contention with the right-wing in Brazil, including conservative members of the Catholic Church. Members of Bolsonaro’s party, Partido Social Liberal, lump Freire into the same “social constructivist” category as Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky whose works they claim have socially engineered a “cultural Marxist” takeover of Brazilian education. Conservative Catholics in Brazil continue to decry Freire’s pedagogy for undermining the traditional authority of the teacher in Catholic education. Of course, criticism of Freire is also part of the trend (all-too-familiar to American teachers, especially during the tenure of Betsy de Vos as Secretary of Education) of reducing the role of the state in education and replacing public education with private or religious schools. Brazil’s authoritarian leader, Jair Bolsonaro, who has famously discriminated against women, Black people, LGBT people, Native people and quilombolas (an ancient community of escaped slaves) and immigrants and who has persecuted leftist unions and social movements, proposed that Saint Joseph of Anchieta, a Spanish-born missionary of the 16th century, replace Paulo Freire as Brazil’s official patron of education. He has described Freire’s work as “Marxist rubbish,” and proposed to “enter the Education Ministry with a flamethrower to remove Paulo Freire.”

Freire’s humanist philosophy was, for Bolsonaro, one that must be driven back. However, the Jesuit rector and vice rector of the National Sanctuary of Saint Joseph of Anchieta in Brazil’s southeastern state of Espirito Santo opposed this idea on the grounds that Joseph of Anchieta was being politically manipulated by the Partido Social Liberal and they made clear that they supported both Freire and Joseph of Anchieta who chose to fight on the side of marginalized and oppressed peoples. I admire the courage and integrity of these two Jesuits for clearly incurring the wrath of Brazil’s president. We need people to stand up and defend critical race theory with similar verve and courage here in the United States.

Yancy: Paulo Freire stressed the absolute importance of dialogue. He writes, “Dialogue cannot exist, however, in the absence of a profound love for the world and for the people. The naming of the world, which is an act of creation and re-creation, is not possible if it is not infused with love.” For Freire, dialogue is integral to who we are existentially, what it means for us to be alive, and to exist as human beings. In fact, domination, for him, is what he sees as pathological and anti-dialogical. We are amidst a climate catastrophe. The earth is suffering. We have proven to be unethical and derelict in our global stewardship vis-à-vis the earth. Ours has been a teleology of absolute domination over the earth regardless of its impact on conditions that must be in place for us to flourish as a species as well as other species. In short, the earth has not been treated as a dialogic partner; we assume that the earth is an “object” to be infinitely drained of its resources, and it is being done so through capitalist greed. Were Freire alive today, what would he say about our violence against the earth, and what might he suggest as a way of moving forward?

McLaren: I believe Freire was deeply concerned about our violence against the earth, as you so eloquently put it, the “teleology of absolute domination over the earth.” He literally wandered around the globe, describing himself in his signature humility as follows, “I am a vagabond of the obvious, because I walk around the world saying obvious things, such as education is not neutral.” Freire, who traveled through numerous countries on his fifteen year exile from Brazil, was a wanderer, but he also walked the world “asking questions” rather than “giving solutions.” He reminds me of the famous Zapatista saying, “andar preguntandos” (walking we ask questions—a horizontal or participatory position that invites dialogue) as opposed to “andar predicando” (walking we go preaching—a “follow me”-oriented position). In other words, Freire rejected being part of a vanguard or high priesthood that possessed the answers to revolutionary change. Wandering into hinterlands unexplored—both intellectual and physical—not only provides opportunities to err, but locates making mistakes in a realm of the pedagogical encounter that provides for the possibility of growth—for recognizing human finitude and our unfinishedness, for transcendence and emancipation.

As my friend Richard Kahn notes, the struggle for eco-justice is multi-faceted and some figures in the field of ecopedagogy influenced by Freire’s work have noted that this did not mean that all of Freire’s positions on this issue were unproblematic or insufficiently developed. That is clearly the case. But just as clearly, Freire’s commitment to the global poor would have, I believe, seen him addressing the issue of climate change, ecocide, and settler colonial epistemicide in a more sophisticated way—a dialogue between social justice and eco-justice would certainly have emerged in Freire’s work. Freire wandered the world and witnessed with great anguish and empathy people starving and suffering disproportionately according to geopolitical alliances involving the so-called First and Third Worlds; he witnessed the human tragedy brought about by resource degradation, capitalist expansion, hyper-industrialization, fossil fuel extraction, global warming, and global ecocide. Freire recoiled from the policy issues put out by countries such as the United States regarding geoeconomics and more importantly still, he identified and resisted the logic of domination that led to advanced capitalist countries exploiting the lands and peoples of the Third World. Most certainly he would have engaged these issues had he lived longer.

The Freirean legacy of critical pedagogy and its affinity to the more recent development of ecopedagogy would have been important to Freire given his willingness to walk with those who toil and suffer and to understand why such suffering takes the forms that it does. Certainly, there were valid shortcomings to Freire’s work which were considered by some critics to be too “human centered” and too “productivist” since the vocation of Freire’s work is to become more fully “human,” to be a Subject who acts “upon” and transforms the world. But I am confident that his work would have increasingly addressed the area of climate catastrophe given his emphasis on dialogue, and he would have increasingly taken criticisms of his work into consideration and his contributions to ecopedagogy would have deepened and expanded significantly over the years, aligning itself more closely to a counterhegemonic globalization from below. I believe he would have addressed some of the considerable tensions within the eco-socialist communities and made important contributions in dialogues with eco-socialists, Red-Greens, Green anarchists and those who work within a deep ecology politics, Communalism and social ecology.

But Freire was largely concerned with developing a politics of liberation through multiple forms of literacy—he was a philosopher of praxis who was in demand mostly by teachers and teacher educators. Yet he was also interested in regional development and agrarian reform. Cultural theorist bell hooks notes that one important reason that Paulo’s book, Pedagogy in Process: The Letters to Guinea-Bissau, “has been important for my work is that it is a crucial example of how a privileged critical thinker approaches sharing knowledge and resources with those who are in need.” He traveled constantly after his exile, from a brief stay in Bolivia, a five-year stay in Chile where he became involved in the Christian Democratic Agrarian Reform Movement and worked as a UNESCO consultant with the Research and Training Institute for Agrarian Reform; a visiting appointment in 1969 to Harvard University’s Center for Studies in Development and Social Change; a move to Geneva, Switzerland, in 1970 as consultant to the Office of Education of the World Council of Churches, where he developed literacy programs for Tanzania and Guinea-Bissau that focused on the re-Africanization of their countries; the development of literacy programs in postrevolutionary former Portuguese colonies such as Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique; assisting the government of Peru and Nicaragua with their literacy campaigns; the establishment of the Institute of Cultural Action in Geneva in 1971; a brief return to Chile after Salvador Allende was assassinated in 1973, provoking General Pinochet to declare Freire a subversive; and his brief visit to Brazil under a political amnesty in 1979 and his final return to Brazil in 1980 to teach at the Pontificia Universidade Catolica de Sao Paulo and the Universidade de Campinas in Sao Paulo. From 1980-1986, he became the supervisor of the adult literacy project for the Workers’ Party in Sao Paulo. Freire worked briefly as Secretary of Education of Sao Paulo, from 1989 to 1992, continuing his radical agenda of literacy reform for the people of that city. Given his curiosity and his voracious capacity for addressing multiple forms of domination, I find it impossible to consider that he wouldn’t engage with questions of settler colonialism, indigeneity, ecopedagogy, and many other issues involving our planetary crisis. We often expect too much from great historical figures during their lifetimes—that is only to be expected.

Yancy: There are times when I wonder to what extent, as a successful academic/scholar, I have become seduced by the structures of that success. After all, we don’t commit “academic suicide,” where we relinquish our authority as defined within academic institutions. Our livelihood is, for the most part, satisfying. By the way, this is not to sidestep all those adjunct professors who earn significantly less money and lack the security that comes with tenure track positions. What I have in mind is where Freire argues, “One of the methods of manipulation is to inoculate individuals with the bourgeois appetite for personal success.” How does one do the work that needs to be done in the name of justice and yet avoid “the bourgeois appetite for personal success”? After all, even if one doesn’t have that appetite, personal success is entangled with structures that perpetuate injustice.

McLaren: That is an important issue, George, to be sure, and one to which I have given some serious thought. I can best speak to how I wrestled with this dilemma in my own personal journey, since for many years I was bitten by the capitalist beast of trying to achieve personal success—working in the academy, doing critical work, and enjoying the “good life.” As we both are fully aware, George, universities overwhelmingly gear professors towards competition at the expense of cooperation and collaboration. There is significant—I would also say relentless—pressure on university intellectuals for receiving personal accolades for work published in the “high prestige” journals which, of course, give your work more legitimacy. I once knew a professor who gained tenure for publishing one article in the Harvard Journal of Education. My first contract as a professor in 1984 was not renewed because students were divided by my pedagogy and there were large marches on campus in favor of my teaching and those who felt I was being “too political” and fortunately for me, I was invited to the United States by Henry Giroux, with whom I had the great opportunity to work with for 8 years, building up a center for cultural studies. Clearly, we were not liked by the “old guard”—some of whom refused to even talk with us. With success and recognition comes risking the reproach by others who feel their work is superior, or more patriotic, or more supportive of the status quo, but have not been able to break out into the limelight. Not long ago I asked someone from a university accreditation organization to what extent they regard publications by faculty in their accreditation process. The answer was that they only count articles in the most prestigious journals. Personally, I find these journals relatively useless for doing critical, social justice research and no longer send them my work. But, of course, I can afford to do that now. I found navigating university life to be challenging.

At numerous faculty meetings I heard one Dean say that what he wanted to hire was both “mules” who would take over the burden of teaching classes—and “stars”—who were preferred, of course, over the mules. Stars were difficult to hire because this meant that many professors who were not stars needed to ratchet up their publishing game and many professors would not vote for the “star” candidates since they didn’t want to work with younger scholars who had already published more than they had. At one of my first universities, there was a lot of resentment towards me because professors felt that my publishing output meant more pressure on them to publish. Once, I had a Dean who suggested to me privately upon my arrival to the university—this sounds weird, but I assure you it happened—that I was now in Los Angeles and because we had a lot of famous donors from the entertainment industry that he could recommend a plastic surgeon whenever I felt I needed some knicks and tucks to enhance my image. It wasn’t a joke.

But at the outset of my work, I understood my socialist politics were far too radical to be embraced by American Universities and that I would always function as an outsider. There is such a thing as wanting to succeed as an outsider. I started traveling internationally in 1987 after Freire invited me to speak at a psychology conference in Cuba, and during that conference educational scholars/activists from Brazil and Mexico prepared gifts for me—copies of some of my works typed out in Spanish and decorated with revolutionary symbols, and souvenirs from their countries they had prepared for me in advance of the conference. I was quite stunned to think that they were familiar with my work, just as I was surprised that Freire was familiar with my work so early in my political project (I prefer the term “political project” to the term “career”). To be honest, I didn’t feel my work deserved this attention but in time in might. That sentiment didn’t last long. During the years 2005 and 2006, I was invited to give talks throughout Venezuela supporting the Bolivarian Revolution (always with a translator since my Spanish was—and remains—very weak). President Hugo Chávez came to meet me in Miraflores Palace and thanked me for bringing a Freirean approach to educators in Venezuela but, in true Freirean fashion reminded me, and rightly so, that any critical pedagogy to emerge from Venezuela could not be transplanted from the outside (a Freirean insight as well) but would come from the Venezuelan people.

I was invited to appear on his television show, Alo Presidente where I sat alongside another guest, the famous Nicaraguan priest and poet, Ernesto Cardinal. Subsequently I was invited to Argentina where my work was gaining attention and had conferences with the children of those who had been tortured and murdered during the dirty war. I was invited to Lapland and eventually throughout Finland where it was a similar story, and this was relatively early in my work as a professor. In Mexico, Instituto McLaren (which began in Tijuana but now resides in Ensenada) was begun by one of Mexico’s communist parties. This early success as an outsider, can—and most often does—inflate the sense of your own worth and I remember my demeanor must have at times been insufferable to many people. There is just as much rivalry among leftist intellectuals and activists—easily as much—as on the right. An unhealthy appetite for personal success—regardless of your political affiliations—tends to encourage you to be less self-reflective about your own work, and more preoccupied with how you are viewed in the very fractious, status-driven arena of universities—places that are decidedly not driven by the cause of liberation.

Success is more predicated on acquiring grant money that filters throughout the university. To make matters worse, those of us on the left are expected to be less preoccupied with bourgeois success, and it brings about feelings of guilt. So here I was living on the Sunset Strip with movie stars as neighbors, hanging out in all the nearby clubs, rubbing shoulders with rock stars and people in the neighborhood knew me as “the Hollywood Marxist.” I was even asked by a movie producer to help draft a script on Che Guevara. When I asked about the focus of the film, he replied, “Che’s sex appeal.” During that time, I was a professor at UCLA and a small group with Republican financial backers created a list of 30 professors which they labelled “The Dirty Thirty” and put me at the top of the list, while offering to pay students 100 dollars to secretly audiotape our lectures and fifty dollars to provide notes from our classes. This received a lot of international media attention and was denounced by newspapers and magazines in dozens of countries as the return of McCarthyism in the US. Such attention—even in the form of attacks—focuses you away from the original reason you joined the academy—to create ideas and analyses and innovative means of participation for the purpose of creating a better, more just world. You begin to enjoy listening to yourself speak, rather than paying attention to those seeking your assistance.

So yes, Freire was able to understand this, and speak against this form of bourgeois academic seduction. Recently one of my favorite colleagues, and a committed Freirean, now retired, received a note from a former student who is now an Assistant Professor and who has embraced an ethic of “who needs it the most” for first authorship of multiple-authored papers. Now that’s especially admirable for an Assistant Professor seeking tenure, who maintained that this principle was adopted from an engagement with Freire’s work that ran through all my colleague’s classes. This may seem a fairly minor example, but it is profoundly Freirean and brushes against the grain of many researchers who fight their colleagues for first authorship. I found that the more I worked with and remained in solidarity with social movements outside of the academy, the more I was able to get back my original focus—although being beaten up by the Turkish military does have its price. Freire’s humility and generosity of spirit were legendary. He embodied a form of what he called “armed love”—a radical love for others, even for the oppressor, a love that inspired him to risk oneself—his reputation, and even his life—for others. Now I am not making a case for martyrdom by any means. Armed love for Freire is a resistance that is both philosophical and affective—I frequently use the word enfleshed. It has a dialectical quality. Marx warned us in the famous eleventh thesis on Feuerbach: “Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.” Philosophical problems arise out of our real-world struggles, and no one understood this better than Paulo Freire.

Yancy: This is my last question and seems apropos. This year marks the 100th anniversary of Freire’s birth? What core truth of his would you like for us to nurture as we celebrate?

McLaren: Earlier you identified the fundamental importance of dialogue in Freire’s work. Dialogue for Freire is not a conversation in the sense of several interlocutors exchanging ideas, despite how interesting those ideas may be, or searching for meaning through debate and discussion over hot tea but is a dialectical encounter carried out in the realm of praxis and that is what makes dialogue for Freire predominately social and political, and distinguishes his concept of dialogue from many other philosophers who use the term. The idea of dialogue in Freire’s work is filled with a multitude of expansive and embracing assertions—that, for example, people who lack humility cannot enter into dialogue, dialogue requires faith in people, only dialogue can create critical thinking, dialogue requires love for people. Freire’s life as a metaphysical wayfarer, scholar, political activist, public intellectual and advocate for poor and suffering peoples was guided by a search for justice that could only be realized through such an expansive and inclusive formation of dialogue. Such an authentic form of dialogue for Freire stipulates engaging both politically and pedagogically the internal contradictions that plagued society. A refusal to enter this type of dialogue has allowed the United States to be transformed, in part, into an anti-Kingdom governed by violence and oppression, and to willfully stand against people of color, against immigrants seeking a better life, against migrant workers, against refugees, against evidence-based truth and the struggle for justice. Dialogue, as Freire employs the term, lays bare the ideological and ethical potentialities for the transformation of society so necessary today as countries are increasingly embracing fascism over democracy, and the racial state. Dialogue requires treating theory as a form of practice and practice as a form of theory as we contest the psychopathology of everyday life incarnate in racism, sexism, misogyny, and capitalism’s social division of labor. It is a fundamental approach to rebuilding the world on an axis of social justice.

That Freirean educators are currently under the vicious scrutiny of fast-developing repressive political forces averse to the very concept of dialogue, especially during a time when we should be celebrating 100 years since Freire’s birth, should worry us all.