As we approached the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., my partner Lisa and I watched all of Eyes on the Prize, the film history of the civil rights movement. Stunning in that history is the utter rage and desperation of the white population of Birmingham and Montgomery and Little Rock as they faced enforcement of the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education desegregation order in the 1950s and early 60s. When nine innocent black children sought to attend Central High School in Little Rock, one young white woman was so distraught that, as one commentator who was there put it, her face was contorted almost beyond recognition with pain and anger; she simply could not believe what was “happening to her.”

What was happening to her? Revealed in her very rage and pain and contortion was that her very self was being ripped away from her. And as I show in Chapter 4 of The Desire for Mutual Recognition, that self is actually a false self, the medium of her recognition as a social person within the nexus of relations that weaved her into what her state governor kept calling “the Southern way of life.” We know that that self is “false” because it is defined by a totally arbitrary “outer” characteristic, the “whiteness” that she experiences on her outside that locates her in an imaginary communion with other whites, an imaginary community that substitutes for an inner absence and inner withdrawnness, an isolation at the very core of her very being. Southern whites in enacting their racist community were not experiencing one another in a relation of I-and-Thou, a relation of authentic mutual recognition of one another’s being. They were not actually present to each other, experiencing the fullness of spiritual mutuality. Rather they were participating in a false community of skin color, which precisely because it was false and merely “outer”, had to keep inflating itself by demonizing their non-white human comrades, who also appeared as merely “outer” to them, whom they could not experience in their true universal humanity.

Thus the imaginary community of whiteness served as a defense against an inner absence and emptiness and deep vulnerability, grounded in fear of each other’s non-recognition of their true social being…and it’s this whiteness-defense that desegregation, with its “mixing” of the races, was threatening to strip away from this woman in the throes of her contortion and rage. Her true fear, however, was not the loss of communal whiteness, the white outer bond, but rather the terror of being thrown back upon her true being as a longing social person, longing from birth to be truly seen and loved and to truly see and love others. Stripping away the whiteness defense threatened her with being revealed as utterly vulnerable to the revelation of her vulnerable deepest humanity, and to the utter humiliation of being seen as longing for the true spiritual bond of I-and-Thou that she had never been allowed to experience in the course of her Southern conditioning. The contortion of her face expressed her inner terror at being robbed of her defensive “way of life,” the nexus of the false sense of “we” that established her in what social connection existed in her world. And in truth that false sense of “we” was not only based on common whiteness, but on the “erotic” energy flows among Southern whites that actually constituted the Southern way of life as a felt web of social practices – from the paddling of children to the romancing of “Gone With the Wind” to an infinite number of other relational customs . By “erotic” I refer not to explicit sexual energy as such, but to the binding embodied energy of the flow of social recognition whose pathological nature is revealed in its association with the absurd outer characteristic of whiteness, imagined absurdly to be a “superior” characteristic, and in many other ways.

In reality, nothing was being taken away from the woman who was beside herself with despair and rage by the nine innocent black children seeking to join her school community. In reality, she was being offered, finally, the opportunity with the end of segregation to reveal herself and see others as fully human, as beautiful embodiments of the deep, universal social being longing for its own mutual recognition that was denied to her in her spiritual imprisonment of the false self and false “we” of her conditioning. But she could not face the terror of the humiliation that nothing would be there if her “white” self was taken away, was denied its segregation and imaginary preeminence.

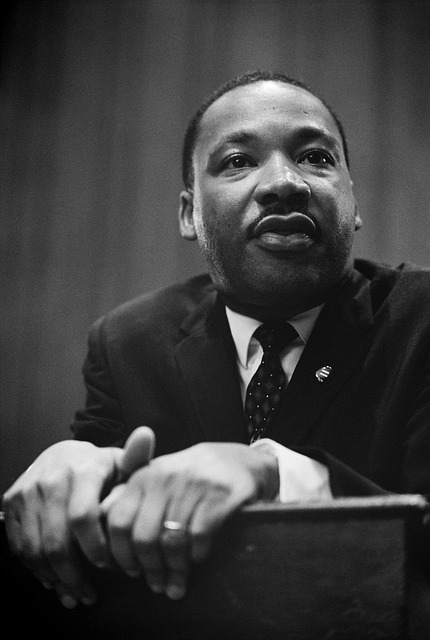

And the same was true for James Earl Ray, Dr. King’s presumed assassin, who 50 years ago on April 4th, felt he had to destroy the person offering him a pathway to a more fully human, fully loving, moral destiny.

For more on the destructive role of imaginary community, see Chapter 4 of The Desire for Mutual Recognition, available from Routledge Press and at Amazon.

__