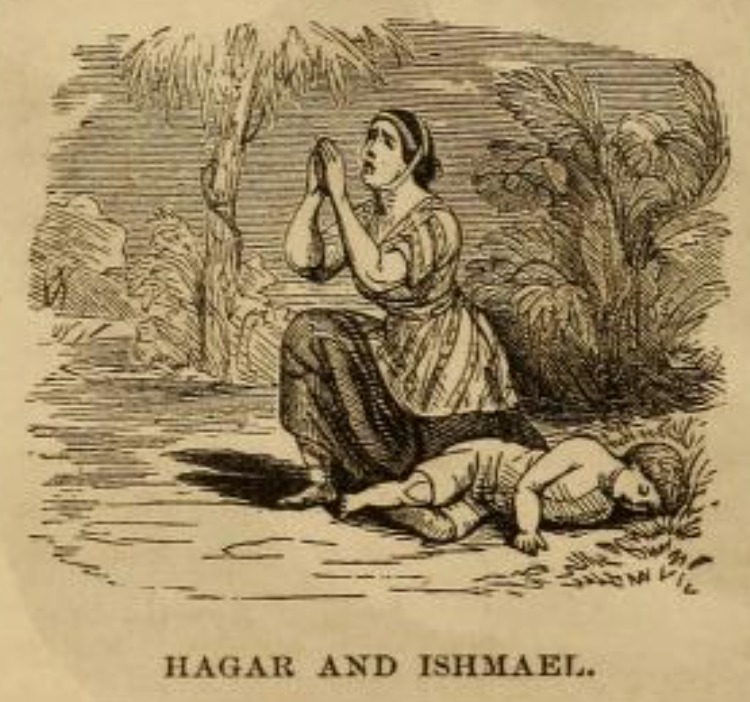

We begin our year by turning the Torah scroll to the story of the first Nakba, the expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael, a story of shame, guilt and moral failure.

Judaism has gone through radical evolutions in its thousands of years of history. But if there is one constant, a single spine to its convoluted DNA, it is the gravity, the trauma, the memory, the omnipresent threat of exile.

From its very founding by the restless migrant who takes the name Abraham, exile drives our common narratives, our greatest tragedies, and – as we are commanded to remind ourselves every year on Rosh Hashanah – our original sin.

We begin our year by turning the Torah scroll to the story of the first Nakba.

We begin our year with our ancestors Abraham and Sarah, their house slave Hagar, and Ishmael, the beloved young teenaged son of Hagar and Abraham. The four live together. Until, that is, Sarah gives birth to Isaac, takes offense at what she perceives as Ishmael mocking her, and tells Abraham, “Throw out that slave woman and her son, for that woman’s son will never share in the inheritance with my son Isaac.”

And there it is. Our real-time 21st century failings foretold, lived out in a story about the 21st century B.C.E.

Abraham and Sarah can’t deal with their guilt, can’t deal with their inability and/or unwillingness to share the land, can’t deal with their horrible treatment of the people who live under their control. So they don’t. Abraham casts them out to wander in the harsh wilderness of Beer Sheva, with little water and food. When the water runs out, Hagar puts the boy under a bush, and walks several paces away from him, sobbing, saying “I cannot watch the boy die.”

God hears her, and comforts her, and saves them from death. This is the Lord which Hagar has given the name Elro’i, the God Who Sees Me.

Abraham, the story tells us, is greatly distressed by it all, but he goes ahead and carries out what he sees as his duty. Ein Mah La’asot, we can hear him say to himself. What can you do?

Today we know him in Israel by a different name. The center-right. Sarah, the hard rightist in our Hebrew political present, seems much less troubled. But she’s a mess as well. And in the blink of an eye, in the public reading on the second day of Rosh Hashanah, fast-forward to the possibility that Abraham will face the unbearable, the threat of sacrificing Ishmael’s younger brother Isaac. And for what?

Exile, the story tells us, is a life sentence for some, and a death sentence for others. Today, we call the consequence of Nakba by a different name. Some dislike the term. Many hate it. But if there’s one Hebrew word that Jews everywhere should learn this time of year, and study at this time of reflection and repentance, this is it: Kibush. Ki is pronounced as “key,” as in a device which can keep all of us in some sense locked up and locked in. And which can keep peace, acceptance, recognition, reconciliation, cooperation, and living together as equals, firmly, permanently, locked out.

It means conquest by force, and also military occupation. It means sacrificing children, whether they are under Kibush or enforcing it.

We have grown far too used to glossing over yet another year of making the Kibush ever more permanent, ever more invasive, ever more hidden from our consciousness, ever more poisonous. We have grown far too used to denying away the knowledge, somewhere in the back of our minds, that every Palestinian mother and child deprived of their home, their freedom, their future, is a new Nakba of its own.

Yes, Kibush is an ugly word. A repulsive concept. And therein lies its power. We should all get used to using it. Just as we should get used to using the word Nakba, studying the enormous suffering it has caused and continues to cause. We need to mark the Nakba, give it its name, in order to begin to seek ways back to healing the rift at the heart of the family of Abraham.

Like the word Nakba, many of us treat Kibush as a curse word, and never utter it. And a curse word it literally is, a word which describes a curse that afflicts all the children of Abraham, Arab and Jew, Israel and Palestinian, whether here or in exile.

There are those, many of them Jews and even evangelical Christians, who will tell you never to use the word. That it doesn’t apply. That you can’t occupy your own land, granted to you by God.

Take it from someone who, in the uniform of the Israel Defense Forces, armed with a heavily loaded assault rifle, spent – lost – large blocks of time away from home and family, occupying first northern Sinai, then western Gaza, southern Lebanon, and the West Bank: Kibush is Kibush. The disaster of occupation. As Nakba is Nakba. The catastrophe of exile.

As Jews, we begin every year commanded to look inward, to redress our wrongdoing. This year, we can begin by giving it its proper names. As a people and as individuals, until we learn to live with our family, the descendants of Abraham, Hagar, and Ishmael, and share with them our inheritance, we will never truly be able to live with ourselves.

[Note: This article originally appeared in Haaretz and is reprinted on Tikkun with permission of the author and Haaretz.]

Wow! Thank you so much for this historic correction. This is powerful!

Oh, if only they would listen. If only the brothers – for they ARE brothers- if only they would embrace each other and share the homeland of both!

Dear Rabbi, I am so glad to learn these words and understand this story more clearly. It is the scourge of our time, dividing one group against another “othering” people who are human beings just like us. May the New Year open all minds and hearts to our essential unity and help us commune, collaborate, love and accept each other.

Thank you Michael for sharing this article, and for your own clarity of history and heart.

L’ Shana Tova

Germanic, Slavic, Anglo, and western hemisphere indigenous all share similar divisions and prejudices…tell me Rabbi Lerner, is there any group, tribe, on this planet who knows peace and will hold to it? we pray that all tribes will unite in the quest to save our planet and ecosystems from the inevitable destruction. perhaps God has begun the process of teaching a lesson on excessive material comforts and unsustainable lifestyles?

Thank you for this intensely disturbing reminder. I never connected Abraham’s thought that he must sacrifice Isaac with his banishment of Ishmael and Hagar. Now it makes psychological sense: guilt. God was angry at him for preferring Isaac- or allowing Sarah’s preference to sway him into exiling his other son. So Abraham wanted to show God how sorry he was- and that he was willing to let go and never prefer one child over another again. But the conclusion: to murder- and murder ones child!- for Reconciliation with God…I’d say “ How barbaric and yet it seems to be, at root, what we do, as believers, all the time. We are being shown, at this point in history, how to start to stop. Name correctly the cruelty and catastrophe. Nakba. Kibush.

Thank you for sharing this profound message. Shalom

Mimi, you are right. Thank you. Bless you.

Nakba. Kibush.

Am in profound agreement with poignant truth that emerges from this article by Bradley Burston, and much appreciate its publication in Tikkun. One may also give kudos to Haaretz, for its fortitude in conveying a view that seems likely to be derided by Israel’s mainstream.

Original sin — that’s a Christian concept with no place in Jewish belief.