Editor’s Note: The two articles below by Tikkun-oriented writers Charles Eisenstein and Jeremy Lent challenge the mainstream champion of the status quo Stephen Pinker and the NY Times columnist (and human rights advocate) Nicholas Kristof in their willingness to promote a view of the world that cheerily suggests that global capitalism is really doing great, despite all that we know to the contrary. Please circulate these to your social media and other friends.–Rabbi Michael Lerner rabbilerner.tikkun@gmail.com

Our New, Happy Life? The Ideology of Development

In George Orwell’s 1984, there is a moment when the Party announces an “increase” in the chocolate ration – from thirty grams to twenty. No one except for the protagonist, Winston, seems to notice that the ration has gone down not up.

‘Comrades!’ cried an eager youthful voice. ‘Attention, comrades! We have glorious news for you. We have won the battle for production! Returns now completed of the output of all classes of consumption goods show that the standard of living has risen by no less than 20 per cent over the past year. All over Oceania this morning there were irrepressible spontaneous demonstrations when workers marched out of factories and offices and paraded through the streets with banners voicing their gratitude to Big Brother for the new, happy life which his wise leadership has bestowed upon us.

The newscaster goes on to announce one statistic after another proving that everything is getting better. The phrase in vogue is “our new, happy life.” Of course, as with the chocolate ration, it is obvious that the statistics are phony.

Those words, “our new, happy life,” came to me as I read two recent articles, one by Nicholas Kristof in the New York Times and the other by Stephen Pinker in the Wall Street Journal, both of which asserted, with ample statistics, that the overall state of humanity is better now than at any time in history. Fewer people die in wars, car crashes, airplane crashes, even from gun violence. Poverty rates are lower than ever recorded, life expectancy is higher, and more people than ever are literate, have access to electricity and running water, and live in democracies.

Like in 1984, these articles affirm and celebrate the basic direction of society. We are headed in the right direction. With smug assurance they tell us that thanks to reason, science, and enlightened Western political thinking, we are making strides toward a better world.

Like in 1984, there is something deceptive in these arguments that so baldly serve the established order.

Unlike in 1984, the deception is not a product of phony statistics.

Before I describe the deception and what lies on the other side of it, I want to assure the reader that this essay will not try to prove that things are getting worse and worse. In fact, I share the fundamental optimism of Kristof and Pinker that humanity is walking a positive evolutionary path. For this evolution to proceed, however, it is necessary that we acknowledge and integrate the horror, the suffering, and the loss that the triumphalist narrative of civilizational progress skips over.

What hides behind the numbers

In other words, we need to come to grips with precisely the things that Stephen Pinker’s statistics leave out. Generally speaking, metrics-based evaluations, while seemingly objective, bear the covert biases of those who decide what to measure, how to measure it, and what not to measure. They also devalue those things which we cannot measure or that are intrinsically unmeasurable. Let me offer a few examples.

Nicholas Kristof celebrates a decline in the number of people living on less than two dollars a day. What might that statistic hide? Well, every time an indigenous hunter-gatherer or traditional villager is forced off the land and goes to work on a plantation or sweatshop, his or her cash income increases from zero to several dollars a day. The numbers look good. GDP goes up. And the accompanying degradation is invisible.

For the last several decades, multitudes have fled the countryside for burgeoning cities in the global South. Most had lived largely outside the money economy. In a small village in India or Africa, most people procured food, built dwellings, made clothes, and created entertainment in a subsistence or gift economy, without much need for money. When development policies and the global economy push entire nations to generate foreign exchange to meet debt obligations, urbanization invariably results. In a slum in Lagos or Kolkata, two dollars a day is misery, where in the traditional village it might be affluence. Taking for granted the trend of development and urbanization, yes, it is a good thing when those slum dwellers rise from two dollars a day to, say, five. But the focus on that metric obscures deeper processes.

Kristof asserts that 2017 was the best year ever for human health. If we measure the prevalence of infectious diseases, he is certainly right. Life expectancy also continues to rise globally (though it is leveling off and in some countries, such as the United States, beginning to fall). Again though, these metrics obscure disturbing trends. A host of new diseases such as autoimmunity, allergies, Lyme, and autism, compounded with unprecedented levels of addiction, depression, and obesity, contribute to declining physical vitality throughout the developed world, and increasingly in developing countries too. Vast social resources – one-fifth of GDP in the US – go toward sick care; society as a whole is unwell.

Both authors also mention literacy. What might the statistics hide here? For one, the transition into literacy has meant, in many places, the destruction of oral traditions and even the extinction of entire non-written languages. Literacy is part of a broader social repatterning, a transition into modernity, that accompanies cultural and linguistic homogenization. Tens of millions of children go to school to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic; history, science, and Shakespeare, in places where, a generation before, they would have learned how to herd goats, grow barley, make bricks, weave cloth, conduct ceremonies, or bake bread. They would have learned the uses of a thousand plants and the songs of a hundred birds, the words of a thousand stories and the steps to a hundred dances. Acculturation to literate society is part of a much larger change. Reasonable people may differ on whether this change is good or bad, on whether we are better off relying on digital social networks than on place-based communities, better off recognizing more corporate logos than local plants and animals, better off manipulating symbols rather than handling soil. Only from a prejudiced mindset could we say, though, that this shift represents unequivocal progress.

My intention here is not to use written words to decry literacy, deliciously ironic though that would be. I am merely observing that our metrics for progress encode hidden biases and neglect what won’t fit comfortably into the worldview of those who devise them. Certainly, in a society that is already modernized, illiteracy is a terrible disadvantage, but outside that context it is not clear that a literate society – or its extension, a digitized society – is a happy society.

The immeasurability of happiness

Biases or no, surely you can’t argue with the happiness metrics that are the lynchpin of Pinker’s argument that science, reason, and Western political ideals are working to create a better world. The more advanced the country, he says, the happier people are. Therefore the more the rest of the world develops along the path we blazed, the happier the world will be.

Unfortunately, happiness statistics encode as assumptions the very conclusions the developmentalist argument tries to prove. Generally speaking, happiness metrics comprise two approaches: objective measures of well-being, and subjective reports of happiness. Well-being metrics include such things as per-capita income, life expectancy, leisure time, educational level, access to health care, and many of the other accouterments of development. In many cultures, for example, “leisure” was not a concept; leisure in contradistinction to work assumes that work itself is as it became in the Industrial Revolution: tedious, degrading, burdensome. A culture where work is not clearly separable from life is misjudged by this happiness metric; see Helena Norberg-Hodge’s marvelous film Ancient Futures for a depiction of such a culture, in which, as the film says, “work and leisure are one.”

Encoded in objective well-being metrics is a certain vision of development; specifically, the mode of development that dominates today. To say that developed countries are therefore happier is circular logic.

As for subjective reports of individual happiness, individual self-reporting necessarily references the surrounding culture. I rate my happiness in comparison to the normative level of happiness around me. A society of rampant anxiety and depression draws a very low baseline. A woman told me once, “I used to consider myself to be a reasonably happy person, until I visited a village in Afghanistan near where I’d been deployed in the military. I wanted to see what it was like from a different perspective. This is a desperately poor village,” she said. “The huts didn’t even have floors, just dirt which frequently turned to mud. They barely even had enough food. But I have never seen happier people. They were so full of joy and generosity. These people, who had nothing, were happier than almost anyone I know.”

Whatever those Afghan villagers had to make them happy, I don’t think shows up in Stephen Pinker’s statistics purporting to prove that they should follow our path. The reader may have had similar experiences visiting Mexico, Brazil, Africa, or India, in whose backwaters one finds a level of joy rare amidst the suburban boxes of my country. This, despite centuries of imperialism, war, and colonialism. Imagine the happiness that would be possible in a just and peaceful world.

I’m sure my point here will be unpersuasive to anyone who has not had such an experience first-hand. You will think, perhaps, that maybe the locals were just putting on their best face for the visitor. Or maybe that I am seeing them through romanticizing “happy-natives” lenses. But I am not speaking here of superficial good cheer or the phony smile of a man making the best of things. People in older cultures, connected to community and place, held close in a lineage of ancestors, woven into a web of personal and cultural stories, radiate a kind of solidity and presence that I rarely find in any modern person. When I interact with one of them, I know that whatever the measurable gains of the Ascent of Humanity, we have lost something immeasurably precious. And I know that until we recognize it and turn toward its recovery, that no further progress in lifespan or GDP or educational attainment will bring us closer to any place worth going.

What other elements of deep well-being elude our measurements? Authenticity of communication? The intimacy and vitality of our relationships? Familiarity with local plants and animals? Aesthetic nourishment from the built environment? Participation in meaningful collective endeavors? Sense of community and social solidarity? What we have lost is hard to measure, even if we were to try. For the quantitative mind, the mind of money and data, it hardly exists. Yet the loss casts a shadow on the heart, a dim longing that no assurance of new, happy life can assuage.

While the fullness of this loss – and, by implication, the potential in its recovery – is beyond measure, there are nonetheless statistics, left out of Pinker’s analysis, that point to it. I am referring to the high levels of suicide, opioid addiction, meth addiction, pornography, gambling, anxiety, and depression that plague modern society and every modernizing society. These are not just random flies that have landed in the ointment of progress; they are symptoms of a profound crisis. When community disintegrates, when ties to nature and place are severed, when structures of meaning collapse, when the connections that make us whole wither, we grow hungry for addictive substitutes to numb the longing and fill the void.

The loss I speak of is inseparable from the very institutions – science, technology, industry, capitalism, and the political ideal of the rational individual – that Stephen Pinker says have delivered humanity from misery. We might be cautious, then, about attributing to these institutions certain incontestable improvements over Medieval times or the early Industrial Revolution. Could there be another explanation? Might they have come despitescience, capitalism, rational individualism, etc., and not because of them?

The empathy hypothesis

One of the improvements Stephen Pinker emphasizes is a decline in violence. War casualties, homicide, and violent crime in general have fallen to a fraction of their levels a generation or two ago. The decline in violence is real, but should we attribute it, as Pinker does, to democracy, reason, rule of law, data-driven policing, and so forth? I don’t think so. Democracy is no insurance against war – in fact the United States has perpetrated far more military actions than any other nation in the last half-century. And is the decline in violent crime simply because we are better able to punish and protect ourselves from each other, clamping down on our savage impulses with the technologies of deterrence?

I have another hypothesis. The decline in violence is not the result of perfecting the world of the separate, self-interested rational subject. To the contrary: it is the result of the breakdown of that story, and the rise of empathy in its stead.

In the mythology of the separate individual, the purpose of the state was to ensure a balance between individual freedom and the common good by putting limits on the pursuit of self-interest. In the emerging mythology of interconnection, ecology, and interbeing, we awaken to the understanding that the good of others, human and otherwise, is inseparable from our own well-being.

The defining question of empathy is, What is it like to be you? In contrast, the mindset of war is the othering, the dehumanization and demonization of people who become the enemy. That becomes more difficult the more accustomed we are to considering the experience of another human being. That is why war, torture, capital punishment, and violence have become less acceptable. It is not that they are “irrational.” To the contrary: establishment think tanks are quite adept at inventing highly rational justifications for all of these.

In a world view in which competing self-interested actors is axiomatic, what is “rational” is to outcompete them, dominate them, and exploit them by any means necessary. It was not advances in science or reason that abolished the 14-hour workday, chattel slavery, or debtors’ prisons.

The worldview of ecology, interdependence, and interbeing offers different axioms on which to exercise our reason. Understanding that another person has an experience of being, and is subject to circumstances that condition their behavior, makes us less able to dehumanize them as a first step in harming them. Understanding that what happens to the world in some way happens to ourselves, reason no longer promotes war. Understanding that the health of soil, water, and ecosystems is inseparable from our own health, reason no longer urges their pillage.

In a perverse way, science & technology cheerleaders like Stephen Pinker are right: science has indeed ended the age of war. Not because we have grown so smart and so advanced over primitive impulses that we have transcended it. No, it is because science has brought us to such extremes of savagery that it has become impossible to maintain the myth of separation. The technological improvements in our capacity to murder and ruin make it increasingly clear that we cannot insulate ourselves from the harm we do to the other.

It was not primitive superstition that gave us the machine gun and the atomic bomb. Industry was not an evolutionary step beyond savagery; it applied savagery at an industrial scale. Rational administration of organizations did not elevate us beyond genocide; it enabled it to happen on unprecedented scale and with unprecedented efficiency in the Holocaust. Science did not show us the irrationality of war; it brought us to the very extreme of irrationality, the Mutually Assured Destruction of the Cold War. In that insanity was the seed of a truly evolutive understanding – that what we do to the other, happens to ourselves as well. That is why, aside from a retrograde cadre of American politicians, no one seriously considers using nuclear weapons today.

The horror we feel at the prospect of, say, nuking Pyongyang or Tehran is not the dread of radioactive blowback or retributive terror. It arises, I claim, from our empathic identification with the victims. As the consciousness of interbeing grows, we can no longer easily wave off their suffering as the just deserts of their wickedness or the regrettable but necessary price of freedom. It as if, on some level, it would be happening to ourselves.

To be sure, there is no shortage of human rights abuses, death squads, torture, domestic violence, military violence, and violent crime still in the world today. To observe, in the midst of it, a rising tide of compassion is not a whitewash of the ugliness, but a call for fuller participation in a movement. On the personal level, it is a movement of kindness, compassion, empathy, taking ownership of one’s judgements and projections, and – not contradictorily – of bravely speaking uncomfortable truths, exposing what was hidden, bringing violence and injustice to light, telling the stories that need to be heard. Together, these two threads of compassion and truth might weave a politics in which we call out the iniquity without judging the perpetrator, but instead seek to understand and change the circumstances of the perpetration.

From empathy, we seek not to punish criminals, but to understand the circumstances that breed crime. We seek not to fight terrorism, but to understand and change the conditions that generate it. We seek not to wall out immigrants, but to understand why people are so desperate in the first place to leave their homes and lands, and how we might be contributing to their desperation.

Empathy suggests the opposite of the conclusion offered by Stephen Pinker. It says, rather than more efficient legal penalties and “data-driven policing,” we might study the approach of new Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, who has directed prosecutors to stop seeking maximum sentences, stop prosecuting cannabis possession, steer offenders toward diversionary programs rather than penal programs, cutting inordinately long probation periods, and other reforms. Undergirding these measures is compassion: What is it like to be a criminal? An addict? A prostitute? Maybe we still want to stop you from continuing to do that, but we no longer desire to punish you. We want to offer you a realistic opportunity to live another way.

Similarly, the future of agriculture is not in more aggressive breeding, more powerful pesticides, or the further conversion of living soil into an industrial input. It is in knowing soil as a being and serving its living integrity, knowing that its health is inseparable from our own. In this way, the principle of empathy (What is it like to be you?) extends beyond criminal justice, foreign policy, and personal relationships. Agriculture, medicine, education, technology – no field is outside its bounds. Translating that principle into civilization’s institutions (rather than extending the reach of reason, control, and domination) is what will bring real progress to humanity.

This vision of progress is not contrary to technological development; neither will science, reason, or technology automatically bring it about. All human capacities can be put into service to a future embodying the understanding that the world’s wellbeing, human and otherwise, feeds our own.

Charles Eisenstein is the author of several books, including Sacred Economics and The More Beautiful World our Hearts Know is Possible. His next book, Climate: A New Story comes out in Fall, 2018.

Steven Pinker’s Ideas About Progress Are Fatally Flawed. These Eight Graphs Show Why.

by Jeremy Lent

Charles Eisenstein recently wrote an insightful critique in Tikkun of Steven Pinker’s triumphalist narrative of progress, with an important focus on the immeasurability of happiness. In this article, I build on Eisenstein’s piece, and argue that it’s time to reclaim the mantle of “Progress” for progressives. By falsely tethering the concept of progress to free market economics and centrist values, Steven Pinker has tried to appropriate a great idea for which he has no rightful claim. I meet Pinker on his own turf, showing that the measurements themselves that Pinker uses are flawed and misleading.

In Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, published earlier this year, Steven Pinker argues that the human race has never had it so good as a result of values he attributes to the European Enlightenment of the 18th century. He berates those who focus on what is wrong with the world’s current condition as pessimists who only help to incite regressive reactionaries. Instead, he glorifies the dominant neoliberal, technocratic approach to solving the world’s problems as the only one that has worked in the past and will continue to lead humanity on its current triumphant path.

His book has incited strong reactions, both positive and negative. On one hand, Bill Gates has, for example, effervesced that “It’s my new favorite book of all time.” On the other hand, Pinker has been fiercely excoriated by a wide range of leading thinkers for writing a simplistic, incoherent paean to the dominant world order. John Gray, in the New Statesman, calls it “embarrassing” and “feeble”; David Bell, writing in The Nation, sees it as “a dogmatic book that offers an oversimplified, excessively optimistic vision of human history”; and George Monbiot, in The Guardian, laments the “poor scholarship” and “motivated reasoning” that “insults the Enlightenment principles he claims to defend.” (Full disclosure: Monbiot recommends my book, The Patterning Instinct, instead.)

In light of all this, you might ask, what is left to add? Having read his book carefully, I believe it’s crucially important to take Pinker to task for some dangerously erroneous arguments he makes. Pinker is, after all, an intellectual darling of the most powerful echelons of global society. He spoke to the world’s elite this year at the World’s Economic Forum in Davos on the perils of what he calls “political correctness,” and has been named one of Time magazine’s “100 Most Influential People in the World Today.” Since his work offers an intellectual rationale for many in the elite to continue practices that imperil humanity, it needs to be met with a detailed and rigorous response.

Besides, I agree with much of what Pinker has to say. His book is stocked with seventy-five charts and graphs that provide incontrovertible evidence for centuries of progress on many fronts that should matter to all of us: an inexorable decline in violence of all sorts along with equally impressive increases in health, longevity, education, and human rights. It’s precisely because of the validity of much of Pinker’s narrative that the flaws in his argument are so dangerous. They’re concealed under such a smooth layer of data and eloquence that they need to be carefully unraveled. That’s why my response to Pinker is to meet him on his own turf: in each section, like him, I rest my case on hard data exemplified in a graph.

This discussion is particularly needed because progress is, in my view, one of the most important concepts of our time. I see myself, in common parlance, as a progressive. Progress is what I, and others I’m close to, care about passionately. Rather than ceding this idea to the coterie of neoliberal technocrats who constitute Pinker’s primary audience, I believe we should hold it in our steady gaze, celebrate it where it exists, understand its true causes, and most importantly, ensure that it continues in a form that future generations on this earth can enjoy. I hope this piece helps to do just that.

Graph 1: Overshoot

In November 2017, around the time when Pinker was likely putting the final touches on his manuscript, over fifteen thousand scientists from 184 countries issued a dire warning to humanity. Because of our overconsumption of the world’s resources, they declared, we are facing “widespread misery and catastrophic biodiversity loss.” They warned that time is running out: “Soon it will be too late to shift course away from our failing trajectory.”

Figure 1: Three graphs from World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice

They included nine sobering charts and a carefully worded, extensively researched analysis showing that, on a multitude of fronts, the human impact on the earth’s biological systems is increasing at an unsustainable rate. Three of those alarming graphs are shown here: the rise in CO2 emissions; the decline in available freshwater; and the increase in the number of ocean dead zones from artificial fertilizer runoff.

This was not the first such notice. Twenty-five years earlier, in 1992, 1,700 scientists (including the majority of living Nobel laureates) sent a similarly worded warning to governmental leaders around the world, calling for a recognition of the earth’s fragility and a new ethic arising from the realization that “we all have but one lifeboat.” The current graphs starkly demonstrate how little the world has paid attention to this warning since 1992.

Taken together, these graphs illustrate ecological overshoot: the fact that, in the pursuit of material progress, our civilization is consuming the earth’s resources faster than they can be replenished. Overshoot is particularly dangerous because of its relatively slow feedback loops: if your checking account balance approaches zero, you know that if you keep writing checks they will bounce. In overshoot, however, it’s as though our civilization keeps taking out bigger and bigger overdrafts to replenish the account, and then we pretend these funds are income and celebrate our continuing “progress.” In the end, of course, the money runs dry and it’s game over.

Pinker claims to respect science, yet he blithely ignores fifteen thousand scientists’ desperate warning to humanity. Instead, he uses the blatant rhetorical technique of ridicule to paint those concerned about overshoot as part of a “quasi-religious ideology… laced with misanthropy, including an indifference to starvation, an indulgence in ghoulish fantasies of a depopulated planet, and Nazi-like comparisons of human beings to vermin, pathogens, and cancer.” He then uses a couple of the most extreme examples he can find to create a straw-man to buttress his caricature. There are issues worthy of debate on the topic of civilization and sustainability, but to approach a subject of such seriousness with emotion-laden rhetoric is morally inexcusable and striking evidence of Monbiot’s claim that Pinker “insults the Enlightenment principles he claims to defend.”

When Pinker does get serious on the topic, he promotes Ecomodernism as the solution: a neoliberal, technocratic belief that a combination of market-based solutions and technological fixes will magically resolve all ecological problems. This approach fails, however, to take into account the structural drivers of overshoot: a growth-based global economy reliant on ever-increasing monetization of natural resources and human activity. Without changing this structure, overshoot is inevitable. Transnational corporations, which currently constitute sixty-nine of the world’s hundred largest economies, are driven only by increasing short-term financial value for their shareholders, regardless of the long-term impact on humanity. As freshwater resources decline, for example, their incentive is to buy up what remains and sell it in plastic throwaway bottles or process it into sugary drinks, propelling billions in developing countries toward obesity through sophisticated marketing. In fact, until an imminent collapse of civilization itself, increasing ecological catastrophes are likely to enhance the GDP of developed countries even while those in less developed regions suffer dire consequences.

Graphs 2 and 3: Progress for Whom?

Which brings us to another fundamental issue in Pinker’s narrative of progress: who actually gets to enjoy it? Much of his book is devoted to graphs showing worldwide progress in quality in life for humanity as a whole. However, some of his omissions and misstatements on this topic are very telling.

At one point, Pinker explains that, “Despite the word’s root, humanism doesn’t exclude the flourishing of animals, but this book focuses on the welfare of humankind.” That’s convenient, because any non-human animal might not agree that the past sixty years has been a period of flourishing. In fact, while the world’s GDP has increased 22-fold since 1970, there has been a vast die-off of the creatures with whom we share the earth. As shown in Figure 2, human progress in material consumption has come at the cost of a 58% decline in vertebrates, including a shocking 81% reduction of animal populations in freshwater systems. For every five birds or fish that inhabited a river or lake in 1970, there is now just one.

Figure 2: Reduction in abundance in global species since 1970. Source: WWF Living Plant Report, 2016

But we don’t need to look outside the human race for Pinker’s selective view of progress. He is pleased to tell us that “racist violence against African Americans… plummeted in the 20th century, and has fallen further since.” What he declines to report is the drastic increase in incarceration rates for African Americans during that same period (Figure 3). An African American man is now six times more likely to be arrested than a white man, resulting in the dismal statistic that one in every three African American men can currently expect to be imprisoned in their lifetime. The grim takeaway from this is that racist violence against African Americans has not declined at all, as Pinker suggests. Instead, it has become institutionalized into U.S. national policy in what is known as the school-to-prison pipeline.

Figure 3: Historical incarceration rates of African-Americans. Source: The Washington Post.

Graph 4: A rising tide lifts all boats?

This brings us to one of the crucial errors in Pinker’s overall analysis. By failing to analyze his top-level numbers with discernment, he unquestioningly propagates one of the great neoliberal myths of the past several decades: that “a rising tide lifts all the boats”—a phrase he unashamedly appropriates for himself as he extols the benefits of inequality. This was the argument used by the original instigators of neoliberal laissez-faire economics, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, to cut taxes, privatize industries, and slash public services with the goal of increasing economic growth.

Pinker makes two key points here. First, he argues that “income inequality is not a fundamental component of well-being,” pointing to recent research that people are comfortable with differential rewards for others depending on their effort and skill. However, as Pinker himself acknowledges, humans do have a powerful predisposition toward fairness. They want to feel that, if they work diligently, they can be as successful as someone else based on what they do, not on what family they’re born into or what their skin color happens to be. More equal societies are also healthier, which is a condition conspicuously missing from the current economic model, where the divide between rich and poor has become so gaping that the six wealthiest men in the world (including Pinker’s good friend, Bill Gates) now own as much wealth as the entire bottom half of the world’s population.

Pinker’s fallback might, then, be his second point: the rising tide argument, which he extends to the global economy. Here, he cheerfully recounts the story of how Branko Milanović, a leading ex-World Bank economist, analyzed income gains by percentile across the world over the twenty-year period 1988–2008, and discovered something that became widely known as the “Elephant Graph,” because its shape resembled the profile of an elephant with a raised trunk. Contrary to popular belief about rising global inequality, it seemed to show that, while the top 1% did in fact gain more than their fair share of income, lower percentiles of the global population had done just as well. It seemed to be only the middle classes in wealthy countries that had missed out.

This graph, however, is virtually meaningless because it calculates growth rates as a percent of widely divergent income levels. Compare a Silicon Valley executive earning $200,000/year with one of the three billion people currently living on $2.50 per day or less. If the executive gets a 10% pay hike, she can use the $20,000 to buy a new compact car for her teenage daughter. Meanwhile, that same 10% increase would add, at most, a measly 25 cents per day to each of those three billion. In Graph 4, Oxfam economist Mujeed Jamaldeen shows the original “Elephant Graph” (blue line) contrasted with changes in absolute income levels (green line). The difference is stark.

Figure 4: “Elephant Graph” versus absolute income growth levels. Source: “From Poverty to Power,” Muheed Jamaldeen.

The “Elephant Graph” elegantly conceals the fact that the wealthiest 1% experienced nearly 65 times the absolute income growth as the poorest half of the world’s population. Inequality isn’t, in fact, decreasing at all, but going extremely rapidly the other way. Jamaldeen has calculated that, at the current rate, it would take over 250 years for the income of the poorest 10% to merely reach the global average income of $11/day. By that time, at the current rate of consumption by wealthy nations, it’s safe to say there would be nothing left for them to spend their lucrative earnings on. In fact, the “rising tide” for some barely equates to a drop in the bucket for billions of others.

Graph 5: Measuring Genuine Progress

One of the cornerstones of Pinker’s book is the explosive rise in income and wealth that the world has experienced in the past couple of centuries. Referring to the work of economist Angus Deaton, he calls it the “Great Escape” from the historic burdens of human suffering, and shows a chart (Figure 5, left) depicting the rise in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, which seems to say it all. How could anyone in their right mind refute that evidence of progress?

Figure 5: GDP per capita compared with GPI. Source: Kubiszewski et al. “Beyond GDP: Measuring and achieving global genuine progress.” Ecological Economics, 2013.

There is no doubt that the world has experienced a transformation in material wellbeing in the past two hundred years, and Pinker documents this in detail, from the increased availability of clothing, food, and transportation, to the seemingly mundane yet enormously important decrease in the cost of artificial light. However, there is a point where the rise in economic activity begins to decouple from wellbeing. In fact, GDP merely measures the rate at which a society is transforming nature and human activities into the monetary economy, regardless of the ensuing quality of life. Anything that causes economic activity of any kind, whether good or bad, adds to GDP. An oil spill, for example, increases GDP because of the cost of cleaning it up: the bigger the spill, the better it is for GDP.

This divergence is played out, tragically, across the world every day, and is cruelly hidden in global statistics of rising GDP when powerful corporate and political interests destroy the lives of the vulnerable in the name of economic “progress.” In just one of countless examples, a recent report in The Guardian describes how indigenous people living on the Xingu River in the Amazon rainforest were forced off their land to make way for the Belo Monte hydroelectric complex in Altamira, Brazil. One of them, Raimundo Brago Gomes, tells how “I didn’t need money to live happy. My whole house was nature… I had my patch of land where I planted a bit of everything, all sorts of fruit trees. I’d catch my fish, make manioc flour… I raised my three daughters, proud of what I was. I was rich.” Now, he and his family live among drug dealers behind barred windows in Brazil’s most violent city, receiving a state pension which, after covering rent and electricity, leaves him about 50 cents a day to feed himself, his wife, daughter, and grandson. Meanwhile, as a result of his family’s forced entry into the monetary economy, Brazil’s GDP has risen.

Pinker is aware of the crudeness of GDP as a measure, but uses it repeatedly throughout his book because, he claims, “it correlates with every indicator of human flourishing.” This is not, however, what has been discovered when economists have adjusted GDP to incorporate other major factors that affect human flourishing. One prominent alternative measure, the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), reduces GDP for negative environmental factors such as the cost of pollution, loss of primary forest and soil quality, and social factors such as the cost of crime and commuting. It increases the measure for positive factors missing from GDP such as housework, volunteer work, and higher education. Sixty years of historical GPI for many countries around the world have been measured, and the results resoundingly refute Pinker’s claim of GDP’s correlation with wellbeing. In fact, as shown by the purple line in Figure 5 (right), it turns out that the world’s Genuine Progress peaked in 1978 and has been steadily falling ever since.

Graph 6: What Has Improved Global Health?

One of Pinker’s most important themes is the undisputed improvement in overall health and longevity that the world has enjoyed in the past century. It’s a powerful and heart-warming story. Life expectancy around the world has more than doubled in the past century. Infant mortality everywhere is a tiny fraction of what it once was. Improvements in medical knowledge and hygiene have saved literally billions of lives. Pinker appropriately quotes economist Steven Radelet that these improvements “rank among the greatest achievements in human history.”

So, what has been the underlying cause of this great achievement? Pinker melds together what he sees as the twin engines of progress: GDP growth and increase in knowledge. Economic growth, for him, is a direct result of global capitalism. “Though intellectuals are apt to do a spit take when they read a defense of capitalism,” he declares with his usual exaggerated rhetoric, “its economic benefits are so obvious that they don’t need to be shown with numbers.” He refers to a figure called the Preston curve, from a paper by Samuel Preston published in 1975 showing a correlation between GDP and life expectancy that become foundational to the field of developmental economics. “Most obviously,” Pinker declares, “GDP per capita correlates with longevity, health, and nutrition.” While he pays lip service to the scientific principle that “correlation is not causation,” he then clearly asserts causation, claiming that “economic development does seem to be a major mover of human welfare.” He closes his chapter with a joke about a university dean offered by a genie the choice between money, fame, or wisdom. The dean chooses wisdom but then regrets it, muttering “I should have taken the money.”

Pinker would have done better to have pondered more deeply on the relation between correlation and causation in this profoundly important topic. In fact, a recent paper by Wolfgang Lutz and Endale Kebede entitled “Education and Health: Redrawing the Preston Curve” does just that. The original Preston curve came with an anomaly: the relationship between GDP and life expectancy doesn’t stay constant. Instead, each period it’s measured, it shifts higher, showing greater life expectancy for any given GDP (Figure 6, left). Preston—and his followers, including Pinker—explained this away by suggesting that advances in medicine and healthcare must have improved things across the board.

Figure 6: GDP vs. Life expectancy compared with Education vs. Life expectancy. Source: W. Lutz and E. Kebede. “Education and Health: Redrawing the Preston Curve.” Population and Development Review, 2018

Lutz and Kebede, however, used sophisticated multi-level regression models to analyze how closely education correlated with life expectancy compared with GDP. They found that a country’s average level of educational attainment explained rising life expectancy much better than GDP, and eliminated the anomaly in Preston’s Curve (Figure 6, right). The correlation with GDP was spurious. In fact, their model suggests that both GDP and health are ultimately driven by the amount of schooling children receive. This finding has enormous implications for development priorities in national and global policy. For decades, the neoliberal mantra, based on Preston’s Curve, has dominated mainstream thinking—raise a country’s GDP and health benefits will follow. Lutz and Kebede show that a more effective policy would be to invest in schooling for children, with all the ensuing benefits in quality of life that will bring.

Pinker’s joke has come full circle. In reality, for the past few decades, the dean chose the money. Now, he can look at the data and mutter: “I should have taken the wisdom.”

Graph 7: False Equivalencies, False Dichotomies

As we can increasingly see, many of Pinker’s missteps arise from the fact that he conflates two different dynamics of the past few centuries: improvements in many aspects of the human experience, and the rise of neoliberal, laissez-faire capitalism. Whether this is because of faulty reasoning on his part, or a conscious strategy to obfuscate, the result is the same. Most readers will walk away from his book with the indelible impression that free market capitalism is an underlying driver of human progress.

Pinker himself states the importance of avoiding this kind of conflation. “Progress,” he declares, “consists not in accepting every change as part of an indivisible package… Progress consists of unbundling the features of a social process as much as we can to maximize the human benefits while minimizing the harms.” If only he took his own admonition more seriously!

Instead, he laces his book with an unending stream of false equivalencies and false dichotomies that lead a reader inexorably to the conclusion that progress and capitalism are part of the same package. One of his favorite tropes is to create a false equivalency between right-wing extremism and the progressive movement on the left. He tells us that the regressive factions that undergirded Donald Trump’s presidency were “abetted by a narrative shared by many of their fiercest opponents, in which the institutions of modernity have failed and every aspect of life is in deepening crisis—the two sides in macabre agreement that wrecking those institutions will make the world a better place.” He even goes so far as to implicate Bernie Sanders in the 2016 election debacle: “The left and right ends of the political spectrum,” he opines, “incensed by economic inequality for their different reasons, curled around to meet each other, and their shared cynicism about the modern economy helped elect the most radical American president in recent times.”

Implicit in Pinker’s political model is the belief that progress can only arise from the brand of centrist politics espoused by many in the mainstream Democratic Party. He perpetuates a false dichotomy of “right versus left” based on a twentieth-century version of politics that has been irrelevant for more than a generation. “The left,” he writes, “has missed the boat in its contempt for the market and its romance with Marxism.” He contrasts “industrial capitalism,” on the one hand, which has rescued humanity from universal poverty, with communism, which has “brought the world terror-famines, purges, gulags, genocides, Chernobyl, megadeath revolutionary wars, and North Korea–style poverty before collapsing everywhere else of its own internal contradictions.”

By painting this black and white, Manichean landscape of capitalist good versus communist evil, Pinker obliterates from view the complex, sophisticated models of a hopeful future that have been diligently constructed over decades by a wide range of progressive thinkers. These fresh perspectives eschew the Pinker-style false dichotomy of traditional left versus right. Instead, they explore the possibilities of replacing a destructive global economic system with one that offers potential for greater fairness, sustainability, and human flourishing. In short, a model for continued progress for the twenty-first century.

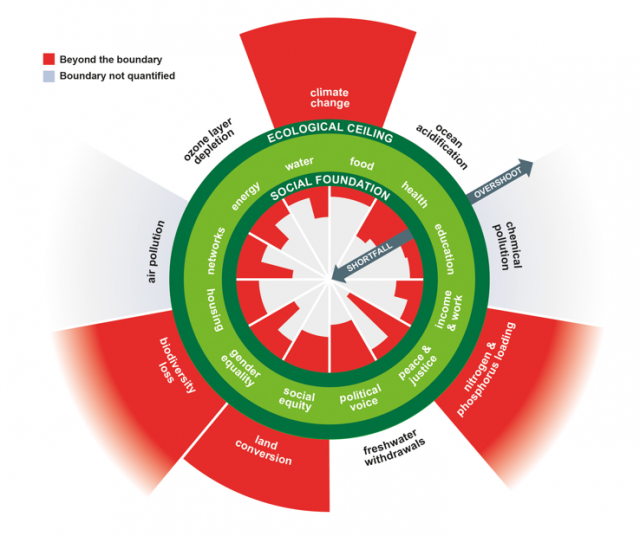

While the thought leaders of the progressive movement are too numerous to mention here, an illustration of this kind of thinking is seen in Graph 7. It shows an integrated model of the economy, aptly called “Doughnut Economics,” that has been developed by pioneering economist Kate Raworth. The inner ring, called Social Foundation, represents the minimum level of life’s essentials, such as food, water, and housing, required for the possibility of a healthy and wholesome life. The outer ring, called Ecological Ceiling, represents the boundaries of Earth’s life-giving systems, such as a stable climate and healthy oceans, within which we must remain to achieve sustained wellbeing for this and future generations. The red areas within the ring show the current shortfall in the availability of bare necessities to the world’s population; the red zones outside the ring illustrate the extent to which we have already overshot the safe boundaries in several essential earth systems. Humanity’s goal, within this model, is to develop policies that bring us within the safe and just space of the “doughnut” between the two rings.

Figure 7: Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economic Model. Source: Kate Raworth; Christian Guthier/The Lancet Planetary Health

Raworth, along with many others who care passionately about humanity’s future progress, focus their efforts, not on the kind of zero-sum, false dichotomies propagated by Pinker, but on developing fresh approaches to building a future that works for all on a sustainable and flourishing earth.

Graph 8: Progress Is Caused By… Progressives!

This brings us to the final graph, which is actually one of Pinker’s own. It shows the decline in recent years of web searches for sexist, racist, and homophobic jokes. Along with other statistics, he uses this as evidence in his argument that, contrary to what we read in the daily headlines, retrograde prejudices based on gender, race, and sexual orientation are actually on the decline. He attributes this in large part to “the benign taboos on racism, sexism, and homophobia that have become second nature to the mainstream.”

How, we might ask, did this happen? As Pinker himself expresses, we can’t assume that this kind of moral progress just happened on its own. “If you see that a pile of laundry has gone down,” he avers, “it does not mean the clothes washed themselves; it means someone washed the clothes. If a type of violence has gone down, then some change in the social, cultural, or material milieu has caused it to go down… That makes it important to find out what the causes are, so we can try to intensify them and apply them more widely.”

Looking back into history, Pinker recognizes that changes in moral norms came about because progressive minds broke out of their society’s normative frames and applied new ethics based on a higher level of morality, dragging the mainstream reluctantly in their wake, until the next generation grew up adopting a new moral baseline. “Global shaming campaigns,” he explains, “even when they start out as purely aspirational, have in the past led to dramatic reductions in slavery, dueling, whaling, foot-binding, piracy, privateering, chemical warfare, apartheid, and atmospheric nuclear testing.”

It is hard to comprehend how the same person who wrote these words can then turn around and hurl invectives against what he decries as “political correctness police, and social justice warriors” caught up in “identity politics,” not to mention his loathing for an environmental movement that “subordinates human interests to a transcendent entity, the ecosystem.” Pinker seems to view all ethical development from prehistory to the present day as “progress,” but any pressure to shift society further along its moral arc as anathema.

This is the great irony of Pinker’s book. In writing a paean to historical progress, he then takes a staunchly conservative stance to those who want to continue it. It’s as though he sees himself at the mountain’s peak, holding up a placard saying “All progress stops here, unless it’s on my terms.”

In reality, many of the great steps made in securing the moral progress Pinker applauds came from brave individuals who had to resist the opprobrium of the Steven Pinkers of their time while they devoted their lives to reducing the suffering of others. When Thomas Paine affirmed the “Rights of Man” back in 1792, he was tried and convicted in absentia by the British for seditious libel. It would be another 150 years before his visionary idea was universally recognized in the United Nations. Emily Pankhurst was arrested seven times in her struggle to obtain women’s suffrage and was constantly berated by “moderates” of the time for her radical approach in striving for something that has now become the unquestioned norm. When Rachel Carson published Silent Spring in 1962, with the first public exposé of the indiscriminate use of pesticides, her solitary stance was denounced as hysterical and unscientific. Just eight years later, twenty million Americans marched to protect the environment in the first Earth Day.

These great strides in moral progress continue to this day. It’s hard to see them in the swirl of daily events, but they’re all around us: in the legalization of same sex marriage, in the spread of the Black Lives Matter movement, and most recently in the way the #MeToo movement is beginning to shift norms in the workplace. Not surprisingly, the current steps in social progress are vehemently opposed by Steven Pinker, who has approvingly retweeted articles attacking both Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, and who rails at the World Economic Forum against what he terms “political correctness.”

It’s time to reclaim the mantle of “Progress” for progressives. By slyly tethering the concept of progress to free market economics and centrist values, Steven Pinker has tried to appropriate a great idea for which he has no rightful claim. Progress in the quality of life, for humans and nonhumans alike, is something that anyone with a heart should celebrate. It did not come about through capitalism, and in many cases, it has been achieved despite the “free market” that Pinker espouses. Personally, I’m proud to be a progressive, and along with many others, to devote my energy to achieve progress for this and future generations. And if and when we do so, it won’t be thanks to Steven Pinker and his specious arguments.

Jeremy Lent is author of The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning, which investigates how different cultures have made sense of the universe and how their underlying values have changed the course of history. He is founder of the nonprofit Liology Institute, dedicated to fostering a sustainable worldview. For more information visit jeremylent.com.

Originally posted in Patterns of Meaning blog, May 17, 2018

We have used more resources in the last 40 years than in the last 40 000 years .And we are not slowing down this is progress towards our own demise.

This is basic, we are using more than the planet can suatain.