“I would like to end this conversation now and focus elsewhere. Is there anything else you want to share before I do that?” This is a simple question, so simple you may wonder why I would start a blog post with it. I chose to start with it, because it is a doorway into understanding what I started calling “needs choreography.” The first person I shared this term with, outside the context in which it was born, wanted to know why “choreography” and not “dance.” The answer is simple and sad: I believe we were evolutionarily designed to do needs dance all the time, without any choreography other than what life provides organically. I also believe patriarchy has diminished our capacity to do that to such a degree that the dance requires rebooting, which is where actual choreography is required, at least in the global north, where living in consciously interdependent relationships is rare. I am writing this piece because having named this capacity and practice, I can now write about what it is, how it functions, why it’s rare, the systemic conditions that prevent this capacity from growing and growing within us, and what we can do, with others, to make this practice more common.

Now comes the context for the question, without which it may sound almost unfriendly, as if I am putting my own desire to do something else in someone’s face. This question was the beginning of training in needs choreography, by request from Emma who, in response to an intuitive invitation from the editor of this post, is making a brief personal appearance to say: “needs choreography is one of the areas where I have limitations in my capacity. At the same time, I see it as an important capacity for being able to move towards the world where we can all thrive. I wanted to take on learning how to do it, and also to open up to sharing here in this post, because I want my experience of building this capacity to be a gift towards the potential blooming of more need choreographers and increased collective capacity to walk towards the vision of a world that works for all.”

Emma and I are in a purpose partnership. One of the ways we sustain the energy required to be as mobilized towards purpose as we both are, is a deep dip we take, every morning, into intimate sharing. Prior to the beginning of this experiment that I am documenting here, we had had a longstanding dynamic, painful for both of us, in which we couldn’t seem to align our spontaneous flow so that we could reliably end that morning time in a place of togetherness. All too often, either I stayed in the conversation longer than I wanted, or Emma was left behind still wanting to talk and complete something which remained dangling for her. More often than not, I was the one to stretch to stay longer until Emma felt complete, at some ongoing cost to me. Finally the day came, recently, when this dynamic itself became the topic of our conversation. That’s when the term “needs choreography” was born.

The next morning, we started the training with the question with which I opened this piece. What this question does, explicitly, is what until then was missing in the implicit needs dance Emma and I had been doing. In only a few weeks, we almost completely shifted out of this dynamic into full co-holding of what we each bring to these moments and many others like them. This piece, written over several weeks, is mostly about that initial dense conversation. It is vulnerable for both of us to share this publicly. We are doing it squarely within our shared purpose, as part of our contribution to collective liberation through our own experimentation.

In few words, what I said that morning gave Emma full information about me: that my spontaneous flow is elsewhere; that I have full willingness to remain in the conversation to bring it to closure; and that the window for that is not indefinitely large. This is the raw material of needs choreography, which, ultimately, is about consciously distributing the resources – in this case of our attention and energy – in a way that cares for all the needs and impacts known to us. This often means shifting, stretching, readjusting, or reconsidering our own needs and attention in the moment in relation to what else is there. This mutual influencing is what, at the deepest level, is my understanding of what life is about: the constant rearranging of everything in continual integration of all volitions.

This is precisely what we lost, all because of the depth of scarcity we have been living in for some millennia, initially in isolated spots on the planet, now almost everywhere.

Beyond scarcity: stepping into needs choreography

Here, again, is the question I asked Emma: “I would like to end this conversation now and focus elsewhere. Is there anything else you want to share before I do that?” Emma’s response was that she had tension in her; a vigilance around the needs choreography thing and a sense of not knowing how to do that yet. I recognized that vigilance as a manifestation of Emma still being in scarcity thinking, within which any of us could be aware of our own flow and contract at the risk of it being clipped if we weave our needs with those of others. Emma is far from alone in this predicament. Some weeks later, on one of my coaching calls, a woman shared a painfully intense version of the same contraction: she literally can’t hear others’ needs for fear she will then give up on her own needs and go along with something that won’t work for her. It’s painfully common.

Scarcity thinking is an either/or frame through which we look at needs and resources: to attend to your needs, I need to give up mine; to assert mine, I ignore yours, or even coerce you. The starting point of needs choreography is a leap into the choice to hold all the needs at once. This is exactly the spot where choreography is needed: we lost the original trust with which almost all of us came into the world; the trust that makes the needs dance possible. I will, quote, as I often do, from Humberto Maturana and Gerda Verden-Zöller: “A baby is born in the operational trust that there is a world ready to satisfy in love and care all that he or she may require for his or her living, and is therefore not helpless.”[1] Each time I read this sentence I am shook up, again, from the radical implications of it. First, that dependence is a feature of being human, especially a new human, rather than a deficiency to overcome. Second, that helplessness is acquired, and is a reaction to conditions we encounter in which others are not orienting to our needs. Helplessness, in other words, is an acquired feature within a patriarchal world that rejects needs and biology, and with them, vulnerability and the unknown.

The relationship between helplessness and dependence is similar to the one between scarcity and finitude. Both emerge, I believe, when the natural, organic mechanisms of flow are interfered with by mechanisms of control. Needs choreography is an attempt, by any of us who have the capacity to do it, to inject sufficient trust and togetherness into the environment so everyone can resume the dance. The dance itself is the simple practice of putting all the needs on the table, seeing what the known and anticipated impacts are of whatever happens, evaluating what resources are available, and making decisions about the flow of those resources, second by second, in infinite togetherness.

Any little bit of scarcity will interfere. Add to that separation and powerlessness, the other two building blocks of our patriarchal mindset, and it’s a miracle we work out anything, ever, with anyone. If we are going to reboot the dance, some of us, those who are both willing and have the capacity, will need to do more than our proverbial share, as simple as that. Instead of only holding our needs and being influenced by those of others, we create a larger imaginary container within ourselves that has room within it for the larger whole. This isn’t just an abstract metaphor. It is quite literal. For me, it means doing the integration within me of all that I hear from all involved in any moment in which the implicit flow of movement is insufficient to care for all that’s unfolding.

Within this container I hold my needs, others’ needs, including the specific desires within them; the constraints; the impacts; and the available resources. Everything in that pile is in constant flux, and my task is to track it, as much as I possibly can, to decide a next step. Only a next step, not the outcome. The outcome is inherently unknowable precisely because everything changes all the time. Hence, the first deep principle of needs choreography is expanding our capacity to let go and relax into the unknown. It’s entirely impossible to do needs choreography, or even needs dancing, if we want to control the outcome. This is the habitual response to living in scarcity: clutching our way into control. This is what we are most fully called to antidote by our needs choreography: our own and others’ attempt to control outcomes. Needs choreography, the commitment to reboot the dance, is our deepest attempt to realign humanity with the flow of life.

Beyond separation: shaping the contours of mutual influencing

Despite the assault on our being that is part and parcel of the domestication that patriarchal socialization imposes on us, all of us retain something of the original flow of our being with which we arrived here, ready to play. When we embrace needs choreography, we can only do it from within and in response to what we have. For Emma, her entryway into needs choreography starts from recognizing that she retained an unusually strong capacity to be aware of her inner flow. This means that as she begins her conscious attempt to focus on both of us, it would still easily happen that her flow will take up the whole space and leave little room for me. Given, in particular, that I have a deep and longstanding pattern, myself, of not making room for my needs when others don’t make room for them, needs choreography with me would mean taking on awareness of my capacity limits. Since needs choreography is aimed at having everyone’s needs tracked and informing each step of the way, that fact that she has such connection with her flow means that in order to form the creative tension the practice relies on, she will need to focus on my needs, as hard as it may be. That’s what will most likely keep both of our needs in the picture. She can only do that from within the trust that I, with my very strong togetherness grounding, would be easily influenced by her needs, by whatever she says, moment by moment. Needs choreography is always about the specific people or other entities present; not a fixed set of steps. It’s always fresh, always attentive to the moment, always changeable.

As we kept tracking Emma’s experience and giving her this input, the next layer that came to the surface was that even though she wanted to let me go, she didn’t know how to do so without feeling it as some sort of violence towards herself, because of the experience of rejection within herself that would lead her to tear herself away rather than let go. Even this was enough to give me a bit more space, because I had more information about Emma’s state, and because what she said indicated at least some degree of holding me within her awareness in the form of wanting to let me go even while not knowing how. Any amount that someone else holds with us is an amount we are not holding alone within ourselves. This is the weaving of togetherness that is a vital element of needs choreography.

The next step in the training was to focus Emma’s attention on tracking larger and larger loops. I asked for what Emma thought was the state of my inner stretching. Once she focused her attention there, Emma was completely accurate in tracking that I still had willingness to engage with her, and that the stretch was growing as we stayed longer in the conversation, and soon would be an overstretch.

This awareness and the practices that emerge from it are what gave rise to the skill of setting thresholds within Convergent Facilitation. It is about mutual influencing, based on relative desire and stretch. The very first question of that morning training could look three different ways and shape the outcome in three different ways:

The original: I would like to end this conversation now and focus elsewhere. Is there anything else you want to share before I do that?

Lower threshold, easier to cross: I would like to end this conversation now and focus elsewhere. Would having another five minutes support you in transitioning with ease? If not, how long?

Higher threshold, harder to cross: I would like to end this conversation now and focus elsewhere. Is there anything else that is truly important for you to share before I do that?

Try these on, and likely you will feel the different energy field that each of them creates. These are some of the ways we convey to each other the necessary information, nuanced, adapted to what we know about ourselves and the other person, open to change. I vastly prefer this to any standardized questions such as “would you be willing for me to do this now?” which I, for one, often find confusing because willingness is a spectrum, not an on/off switch. When I did road trips with my nephew years ago, we had a simple system to measure willingness: green, yellow, red. When one of us said green, it was a sign of easy willingness, so easy that it’s almost a way to say that our own desire was already aligned, or fully shifted, when hearing what the other wanted. Yellow meant it was a stretch, and still an easy stretch. Red meant it was a big stretch that whoever said it would only be willing to do if it was really important for the other. This last one is particularly important for understanding mutual influencing: the more I know about what you need and why it’s important to you, the more I orient in that direction and find greater willingness.

One core insight I learned from Genevieve Vaughan’s work on the maternal roots of the gift economy (see her edited collection by that title) is that we are a mothering species. This means all of us, not just mothers: all of us are alive because of the willingness of someone, usually though not always our own mother, to give to us unilaterally and unconditionally. We came into being through receiving gifts. When we are exposed to this way of being throughout our life and not only in infancy, and when this way of being happens in community with others and not only in relationship to one individual, we learn the needs dance. When we don’t, needs choreography is vitally essential.

In the absence of both, negotiation is the best we know to do. Negotiation happens across a very clear line of separation. Sometimes it looks almost like a civilized “fight.” And, still, from the vantage point of thinking about needs, it’s obvious to me that even negotiation couldn’t exist without our human capacity for mutual influencing. What feels like a loss to me is that in our separation, we have lost our trust that our needs, by themselves, have the capacity to influence others. Instead, we have been trained, for millennia, to provide compelling reasons for our positions, so as to be able to wrest more from the other party in an adversarial process that is, ultimately, rooted in deep mistrust that we matter, that we have the power to co-create outcomes with other people, and that solutions that work for all could emerge if we hold things with sufficient togetherness.

Togetherness is the heart of needs choreography. This is why I, and a few others I know who spontaneously do needs choreography, focus much more on establishing togetherness than on the specific outcome. With enough togetherness, even when we don’t find a solution, we can still be together and mourn. Without it, it’s harder to mobilize the energy to look for something that will truly work for all. With it, we almost can’t not do it.

Beyond powerlessness: finding the yes and the no

The intensity of the reaction that we so often have when we are immersed in the scarcity mindset is likely to be larger than anyone can carry, no matter how strong their needs choreography capacities. In this case, what was important next was simply to bring tenderness to the reaction; to soften it rather than attempt to find a solution that will attend to the fullness of the needs present. Both Emma and I acknowledged that her needs were more than what I had to give at that moment. All we could do – and that’s already a lot! – was to recognize, together, that the experience of being left was going to be there no matter what I did. That was a huge relief for me, because I, too, have been shaped by patriarchy, which means I still carry the either/or within me, to some extent too. The form it takes is some sense of deep responsibility to care for all that comes my way, without honoring my own limits.

Instead, we came to see that what was needed, which would empower Emma, was to shift things to a dialogue within herself, not with me. That I would go and focus on what was within my flow and purpose, and the rest of the work would happen without me there. It was clear Emma would easily let go if she perceived a greater need within me, such as an appointment with someone in distress, or a physical limit. That meant that it was possible, and it involves choice in a place that, for many of us, is extremely fragile and almost non-existent: the possibility of stretching into a “yes” in this case, and the possibility of stretching into a “no” in other situations. In that moment, Emma found the strength to take in my limits, to say yes to them, and to let go. It was the beginning of seeing the possibility that her own flow could be strong enough to flow with others.

In stark and perhaps counterintuitive terms: rebooting the needs dance cannot happen without finding choice, without learning to say yes and to say no with full simplicity and openness, and without learning to receive a no from others and find other creative paths.

We need the fullness of our power to be able to dance with others. To say yes we need to reconnect with generosity, the ease and joy of saying yes from orienting to others’ needs, and with the trust that giving won’t take away from us; that the same flow we give to is enough to also care for each of us.

To say no we need to reconnect with the full trust that nothing depends, specifically, on any one person or one strategy. Our “no” is important information without which a true solution that works for all can’t be found. It is only through holding all the needs, all the impacts, and all the resources that are available that we can find a solution that works for all.

To receive a no and remain open and connected requires trust in our own mattering that is deep enough it no longer depends on others affirming it. We all needed that affirmation early on in life. Neither Emma nor just about everyone else has received enough early affirmation that our presence, our needs, impacts on us, our pains and joys, our gifts, and everything else about us made a dent in others’ choices and orientation. This is the initial shock of being born into a patriarchal world that I recently wrote about in my article “The Power of the Soft Qualities to Transform Patriarchy.” This is how we lose our power: the no we receive upon entry is bigger than our capacity to metabolize it. While no one can ever give us, as adults, what we could only get as infants, we can share with each other a soft landing for the work of mourning that loss. And, through that, to regain trust in life even with all that has happened to us, individually and collectively.

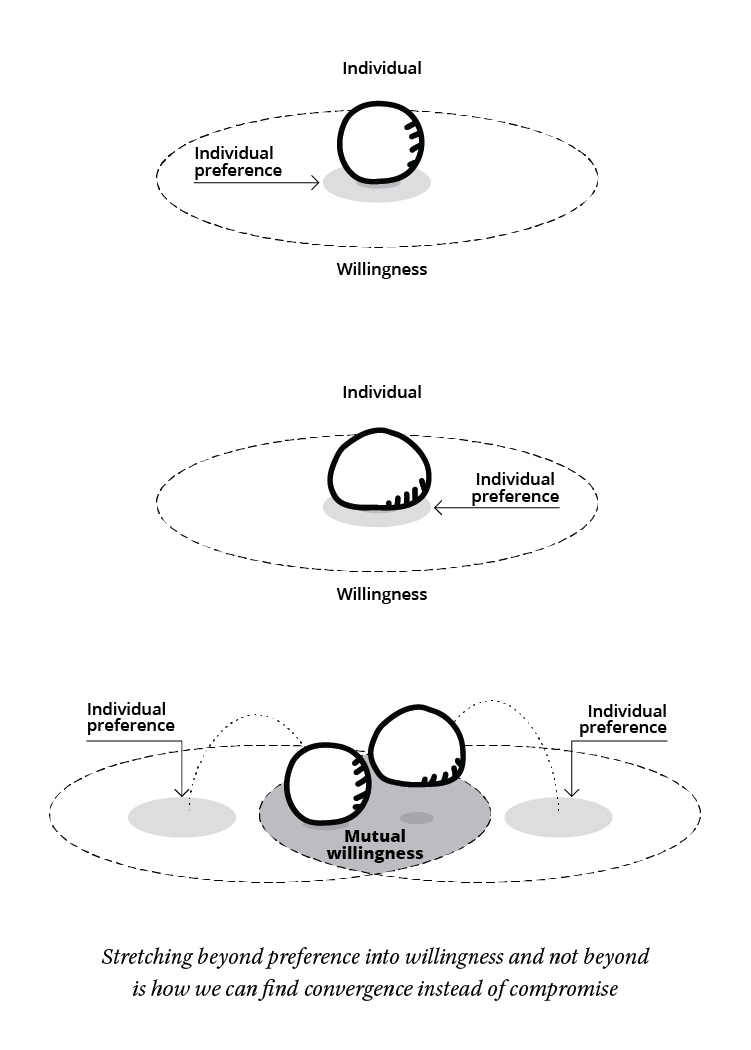

When we can do it, the end point of the dance is finding where willingness exists. Knowing what I want, you shift. Knowing what you want, I shift. My willingness grows as I learn of your circumstances. Your willingness grows as you learn of my circumstances. Our yes and our no interact. Eventually, even as our preferences remain and are decidedly not aligned, we will find a place of mutual willingness within which we can both attend to what matters to us and continually reweave togetherness and restore trust in the flow. This understanding is one of the deepest insights that makes Convergent Facilitation possible.

The journey of liberation never ends

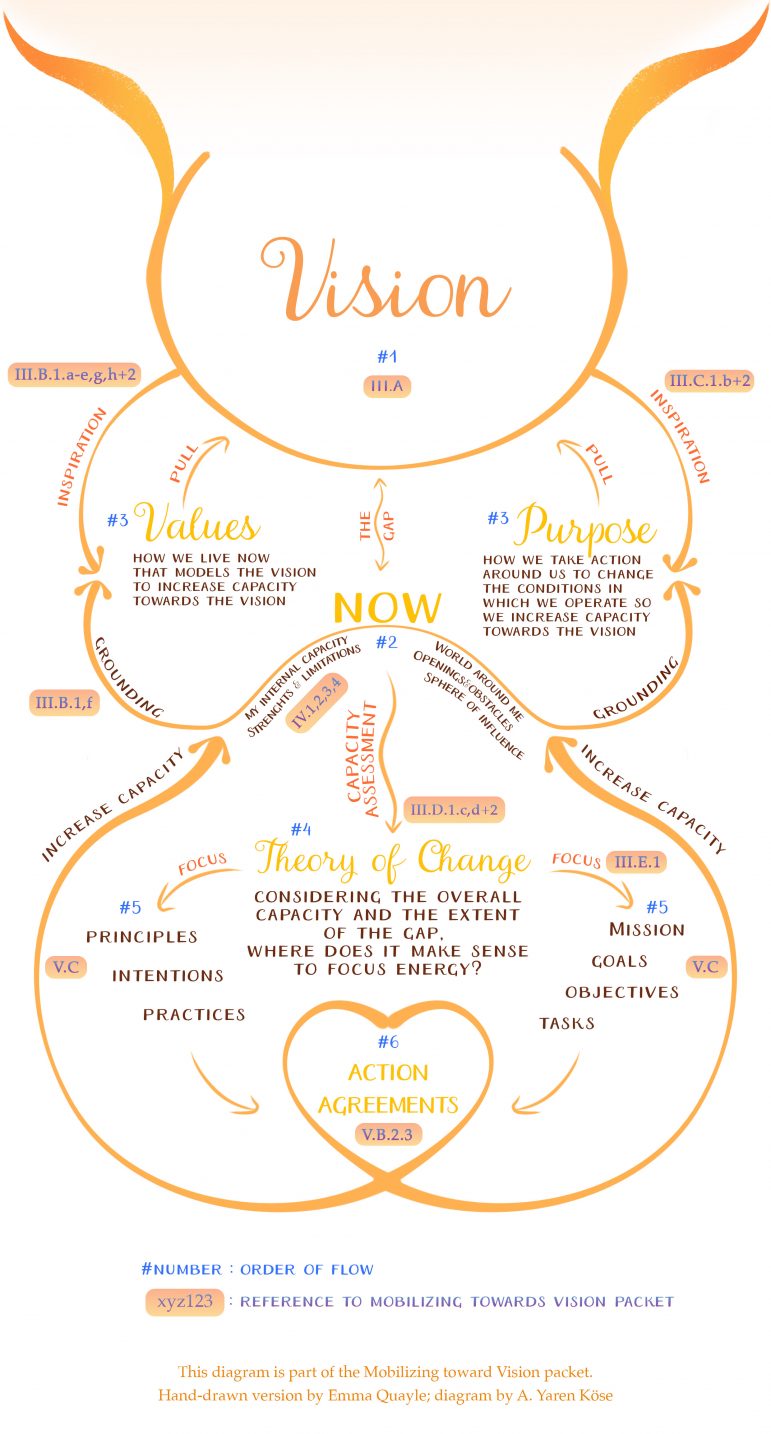

With the degree of commitment to liberation that Emma and I share, I am by now not surprised we found a way forward and out of the dynamic that had previously been so deeply entrenched. In addition to each of us having our own fierce commitment to liberation, it is deeply anchored within our purpose partnership, and we are surrounded by others who are fully committed to their own liberation and to supporting all of us on our journeys. All of us are working with the Vision Mobilization framework that is now central to the work of the Nonviolent Global Liberation community.

All of us use agreements with ourselves and others to support us in aligning, ever more rapidly and fully, with the largest vision possible, doing all and only the necessary healing for that, no more and no less. It’s breathtaking in its intensity and beauty. We are less and less alone by the day, setting ourselves and each other with support to engage with the obstacles along the way. And they are many.

For myself, as a needs choreographer for many years, I had adopted a very strong practice of yes, and an extremely weak practice of no. From a deep orientation to others’ needs, I was committed to saying yes unless it clashes with integrity. Nothing in this commitment attended to the limits of my capacity. I had put on myself an immense weight which others saw more than I did. I now see that it, too, emerged from some version of scarcity: that if I don’t say yes, there would be no other strategy to care for what’s important to whoever made the request of me. It is getting clearer to me now, one more step on the path to liberation: I didn’t learn fast enough to say “no” more often to match the increase in my visibility in the world. I kept stretching, beyond capacity, because of immense care. I still want no one to suffer impositions or aloneness. And I kept overdoing it. I still do, though less. And this overstretching impacted my resilience. This lack of resilience also means that I carry a lot of grief about people not seeing the care I put into all that I do, and thus I still become reactive and less able than I want to receive feedback.

Then I took on, about a year ago, the practice of putting my needs on the table, exposing impacts on me, and honoring my limits. There has been so much learning and shifting from that, and still not enough. Now, recently, I have taken on a broader and more rigorous practice of saying no, which includes and goes beyond asserting my needs, impacts on me, and my limits. Because saying no, for me, is not just when requests are made of me. It’s about saying no to overstretching as a whole. I have a “no buddy” that I share with what I am saying no to, why, and what I mourn about it. I am stunned by seeing how often, already, my functioning in this way has had a significant positive impact on projects and relationships, even if it results in immediate discomfort for some. I am mourning, more often than not, that I hadn’t said no before, even seven years before in some cases. I am mourning that the conditions are such that I would need to say the no instead of there being more alignment with purpose and values elsewhere that would require me to say no less often. Some of the time I mourn that I actively want to say yes to more than I have capacity for. And some of the time I mourn, simply, the impact of the no on another person. Each no makes the next one easier and increases the range of situations within which I find capacity to assert myself. I hope improving my no practice will also increase my capacity to remain open to hearing feedback about the impact of my actions, even when based on not seeing the care that’s there, even when based in reactivity or patriarchal interpretations. I want to, and this, too, may be beyond my capacity given my history of being bullied and being so different for so many years. I don’t know whether or when that will happen.

And the journey is incomplete. It still feels utterly awful at times to even imagine saying no. It feels like I am joining the bullies and becoming like them. And at the very same time it feels absolutely necessary to learn how to embrace this more and to learn to do this with softness. That appears to be my next task. I quote from one of my supporters in the last few weeks: “I am recognizing the importance of what you say about holding the edges of your stretching. Tenderly. With softness both for the other who bumps up against them and for yourself for having edges, current limitations. Owning the limits that permit your continued existence. When you stop doing that you are sacrificing yourself. It could be a decision to make. If the issue and sacrifice would contribute more than your continued living is likely to do. Meanwhile, there’s that limit to your stretching.”

Yes. I want to be one of those who stretch more than others, because we can. We need to have enough of us to reboot the dance. Some of us who will commit to practicing unilateral integration of needs, impacts, and resources, even when others are steeped in scarcity, separation, or powerlessness and unable to participate. And we will need to learn, also, to include in the integration our own needs, the impacts on us, and the limits of our capacity. These are the tasks of the needs choreographers. Before I die, I hope to leave behind enough needs choreographers who are on a self-correcting path of liberation. I can’t think of a better contribution I can make to the possibility of a livable future.

- The Origins of Humanness in the Biology of Love, 214. ↑

Photo Credit

Early affirmation – Barney Moss on Flickr