My sense of safety and belonging as a Jew in America was shattered in 2017 by the White supremacist riot in Charlottesville and Donald Trump’s claim that there were “nice people on both sides.” Then came a barrage of anti-Semitic hate crimes: The massacre at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue. The killings in the kosher market in Jersey City. The home invasion on Hanukkah of a rabbi’s residence in Monsey. The assaults on Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn. The signs and symbols brandished by the Trump insurrectionists who stormed the Capitol: “Camp Auschwitz.” Swastikas. Crusader Crosses. The Proud Boys slogan, “6MWE”—Six Million Wasn’t Enough.” Not to mention the avalanche of malicious memes and neo-Nazi dog whistles on the internet. And just the other day, the terrifying eleven-hour siege by a hostage taker at a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas.

When it gets really scary, the child within me takes cover in the cellar of my psyche shouldering the same dread she felt when she was waiting for Hitler to invade Queens. Then I trusted my parents and their fellow air raid wardens to protect us from a shock attack. Now I worry because, before the pandemic my synagogue on the Upper West Side, a neighborhood synonymous with Jewish New York, posted at our front door a small gray-haired gentleman who checked everyone’s backpacks with a flashlight while shuls all over the country were conducting active-shooter drills and hiring armed guards to buttress police security patrols. On the High Holy Days, with a thousand Jewish worshippers inside and only two NYPD cops assigned to us, I felt exposed and vulnerable. Before COVID, when we were still attending shabbat services in person, I found myself gravitating to a seat close to an exit. And after news broke that the feds had foiled a terrorist plot against a Jewish Federation in the Midwest, I thought twice about attending an event at the Manhattan JCC, where concrete barricades already sprout like mushrooms from the sidewalk to protect the building against a car bomb. Suddenly, grim questions that would have been unthinkable five years ago pushed to the front of my paranoid reveries: Where will they hit next—a Jewish wedding, conference, senior center, day camp, kosher restaurant? How bad does it have to get before we pack up and leave? Where would we go? How would we persuade our kids and grandkids to go with us?

As if those concerns weren’t chilling enough, I became increasingly troubled by a newly energized, if ancient, phenomenon that, in its way, was as alarming as the spike in anti-Semitic violence. I’m referring to attacks on Jews by Jews, or, in the words of Jeffrey Goldberg, editor of The Atlantic, “the intimate-enemy problem.”

The problem crystallized for me when a number of Jewish intellectuals and pundits vilified Peter Beinart, a gifted writer, political analyst, and all-around “credit to our people”—Yale graduate, Rhodes scholar, former editor of the New Republic, professor at CUNY, contributor to prestigious periodicals, observant Jew who attends an Orthodox synagogue and sends his children to a Jewish day school—for the article he published in 2010 in the New York Review of Books and expanded in his book The Crisis of Zionism. His crime was to critique Israeli policies in the West Bank and condemn the American Jewish Establishment for its knee-jerk support of Israel’s government regardless of the morality of its actions. At that point Beinart identified as a liberal Zionist, and in the interest of the Jewish State, he warned the American Jewish community that our youth were feeling increasingly alienated from Israel because they could not reconcile their progressive liberalism with the increasingly hardline Zionism of their elders.

A barrage of acid-barbed arrows came at Beinart from all directions: “Why does he hate Israel so?” asked Daniel Gordis, a conservative, in the Jerusalem Post, before offering his own answer, that “Beinart’s problem isn’t really with Israel. It’s with Judaism.” Bret Stephens, then a columnist for the Wall Street Journal, called the book “an act of moral solipsism.” Jonathan Rosen, an editor and novelist, writing in the New York Times Book Review, accused Beinart of employing “formulations favored by antisemites.” Jeffrey Goldberg, of The Atlantic, said, rather than “devise ways to get Israel to do what he wants,” Beinart chose instead to “make himself feel good about his moral superiority.” Summing up the ad hominem onslaught, New Yorker editor, David Remnick correctly observed, “There is a big difference between critiquing Peter Beinart’s book on the basis of what you might think of his argument and attacking Peter Beinart personally.”

In 2014, I was the target of a mini version of the personal assault on Peter. It happened at a political meeting in Midtown Manhattan. I’d just finished signing the attendance sheet when the woman at the registration table, noticing my name, suddenly shouted, “Letty Cottin Pogrebin!” in a voice loud enough to summon a taxi. Then, wagging her finger in my face, she snarled, “Why are you trying to destroy The Jewish People?”

“Excuse me?” I’d never met the woman before and the meeting was about pro-choice Democratic candidates not about Jews, yet she kept yelling that I was an “enemy of Israel,” a “traitor to The Jewish People,” and a “self-hating Jew.” Kids in my old Queens neighborhood responded to name-calling with, “Sticks and stones can break my bones, but words can never hurt me!” The woman didn’t hurt me; she scared me. No Jew had ever looked at me with that much hate.

It took me a while to deduce the source of her wrath: an open letter to Mayor Bill de Blasio published in the New York Times in which I and fifty other progressive Jewish activists had objected to the mayor having met with leaders of AIPAC, the Israel lobby, and promised them that “City Hall will always be open to you because that’s my job.” Our letter stated that pandering to lobbyists for a foreign country appears nowhere in the mayor’s job description. I assured my hot-headed adversary that I would be equally critical of de Blasio had he promised an Arab American group privileged access to lobby him on behalf of the Palestinians. That neither satisfied nor stopped her. She continued her harangue as if shaming me in front of everyone within earshot would inoculate me against ever again expressing an opinion about AIPAC, Israel, The Jewish People, or anything else. Her strategy—to silence by vilification— has become distressingly familiar.

I survived more than my share of scabrous sexist vilification in the early days of the women’s movement, so I’m pretty impervious to personal attacks. As I did in response to antifeminist smears, I try to meet hostility about my views on the Middle East, whether from the left or right, with as much reason and dignity as I can muster. If a fellow Jew accuses me of condemning Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians while ignoring other nations’ egregious human rights records, I explain that, though I follow world news, Israel is the only country besides my own whose actions affect me viscerally and since I’m a citizen of the US and a soul mate of the State of Israel, I choose to make those two countries my priority. If a fellow Jew asks me how come there are no Palestinians as critical of their people’s misconduct as I am of Israel’s misconduct, I say, many Palestinians have called out corruption in the Palestinian Authority or bad acts by Arab extremists, but the media only pay attention to Palestinians when they ramp up the violence. My question is, why should Palestinians have to act morally before I can pass judgment on Jews who don’t?

If a fellow Jew accuses me of focusing disproportionately on Israel’s political missteps rather than taking pride in the miracle of the nation’s technological and scientific achievements, I tell them I’m immensely proud of Israeli innovation and many other things about the Jewish State. To name a few, the fact that per capita it leads the world in university degrees, PhDs, physicians, engineers, museums, orchestras, books read and published; and it’s the only country in the Middle East where Christians, Muslims, and Jews are all free to vote, and women and homosexuals enjoy full political rights. However, what a country does right, however impressive, must not be used to whitewash what it does wrong.

I feel entitled to criticize Israel not just on the grounds of free speech but because I think of Israelis “as family.” That phrase used to sound corny coming out of my mouth until I learned from a national survey that more than 70 percent of Jews in the US employ the same metaphor. The poll conducted in 2019 by the American Jewish Committee found that 13 percent of US Jews consider Israeli Jews as siblings, 15 percent see them as first cousins, and 43 percent as extended family. When I was small and my dad was always rushing off to meetings, I thought he loved Zionism more than he loved me. You might say Israel was my sibling rival. But on May 14, 1948, a month before my ninth birthday, when the UN declared Israel a state, and my parents and I literally danced in the street outside the Jamaica Jewish Center, the new nation and its hardy pioneers acquired a utopian glow and a familial connection. Israel and I grew up together. I witnessed its wonders and worried through its wars. And, over time, as its flaws and misdeeds became widely known and could no longer be explained away, I felt about Israel as I would about a cousin I love but whose behavior troubles me deeply, a cousin I believe can do better.

These fulminations came to a boil in 2018 when the Israeli Knesset passed the “Nation-State Law,” which, with the stroke of a pen, diminished the civil rights of the country’s non-Jewish citizens and demoted Arabic from its formerly equal status with Hebrew as an official language of the state. When the law was first proposed, Mordechai Kremnitzer, former dean of Hebrew University Law School and a senior fellow at The Israel Democracy Institute, expressed the opinion of many Jews around the world when he said, “This is not a deed worthy of being called legislation, this is an aberrant use of the arbitrary force of the majority to deliberately harm the minority. If this is allowed to pass, we won’t have anywhere to hide our shame.”

Once the bill became law, Kremnitzer went on the radio, broke down in tears, and said he was “ashamed as a Zionist patriot.” Passage of the Nation-State Law also became a breaking point for Avrum Burg, an Israeli with impeccable Zionist credentials. The son of the Orthodox rabbi who founded the National Religious Party and represented the NRP in the Israeli Cabinet, Burg himself was a former leader of the Labor Party, speaker of the Israeli Knesset, and chair of The Jewish Agency. Referring to the new law, Burg declared that non-Jews “will suffer from having an inferior status, similar to what the Jews suffered for untold generations. What is abhorrent to us, we are now doing to our non-Jewish citizens.” (Emphasis added.) His abject shame at this erosion of fundamental democratic rights drove Burg in 2020 to petition the Israeli Supreme Court to do something unthinkable just a few years before: he asked them to rescind his national status as a Jew. Like Kremnitzer and Burg, many Jews around the world feel personally shamed by the Knesset’s brazen contradiction of the bedrock principles contained in the nation’s Declaration of Independence, its foundational document, which explicitly guarantees that the State of Israel “will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race, or sex.” Complete equality.

The Nation-State Law also violates sacred Jewish texts. It flies in the face of “You shall not oppress the stranger for you were strangers in the land of Egypt,” the only commandment in the Torah that is repeated thirty-six times. It flouts one of the most powerful edicts in the Book of Deuteronomy, “Tzedek tzedek tirdof” (Justice justice shalt thou pursue). If, as believing Jews maintain, nothing in the Torah is superfluous and every word is there for a reason, then neither the doubling of the powerful noun “justice” nor the choice of the action verb “pursue” is accidental. As one young social activist put it, “The Torah is jumping up and down and waving its arms at us” to underscore something basic to the ethos of Judaism: that it is not enough for Jews to pray for, long for, commit to, or espouse justice. We must pursue it until every injustice is obliterated. With these texts and this heritage, I cannot understand how any Jew could not be ashamed of Israel’s Nation-State Law, which blatantly reifies unconscionable acts committed by our people against another people whose powerlessness and yearning for self-determination should remind us of our own.

Painful as it is to criticize a beloved family member, I find it harder to stand on the sidelines while the state that began as a gleam in the eyes of its founders, and the people whom God intended to become a “light unto the nations” continue to stumble into the dark night of a xenophobic theocracy. Just as a cousin’s misdeeds are more disquieting to us than the misdeeds of a stranger, it’s inevitable for a Jew like me to experience greater distress when Israel violates its democratic ideals than when, say, Poland or Venezuela does something patently autocratic. And just as I never mistook the Trump administration for “the American people,” I refused to conflate Israel’s right-wing governments with “the Israelis” or “The Jewish People.” I’m with Mark Twain who said, “The only rational patriotism is loyalty to the Nation all the time, loyalty to the Government when it deserves it.

The late David Hartman, a revered American Israeli rabbi, writer, philosopher, and founder of the Hartman Institute, once advised Jews who live in the diaspora, “When you criticize Israel, do it like a mother, not a mother-in-law.” I take his point. Most mothers criticize out of love with the goal of improving their children. I don’t mean to stereotype mothers-in-law since I am one, but it stands to reason that, compared to one’s mother, a mother-in-law’s motives may be less pure. When I criticize Israel’s shandas—be it the IDF’s dehumanizing treatment of Palestinians, the racist or undemocratic laws passed by the Knesset, or the unchecked power of ultra-Orthodox rabbis to decide who may marry whom or pray at the Western Wall—I do it from a place of love. My shame is an expression of the values I learned from my faith and my family.

And those values do not permit me to stand idly by when proponents of Israel-right-or-wrong attack their ideological opponents as enemies of the state or self-hating Jews, or employ other shaming epithets to stifle the free exchange of ideas.

In 2021, Israel’s military chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Aviv Kochavi, recalled the disastrous results of Jews’ lack of solidarity in the distant past. Referring to the armies of the future Roman emperor, he said: “While Titus’s troops gathered outside Jerusalem, the Jewish fighters refused to unite within, and when factionalism pre-vailed over patriotism, the Romans prevailed over the Jews.” Faced with contemporary White supremacists such as David Duke and Richard Spencer, or Jew-hating acolytes of Louis Farrakhan, now is not the time for us to be setting each other on fire. If factional rifts continue to divide our ranks, we will soon find ourselves incapable of unity and solidarity against today’s equivalents of the Romans and the very real threat they pose to our rights, safety, and someday, God forbid, our lives.

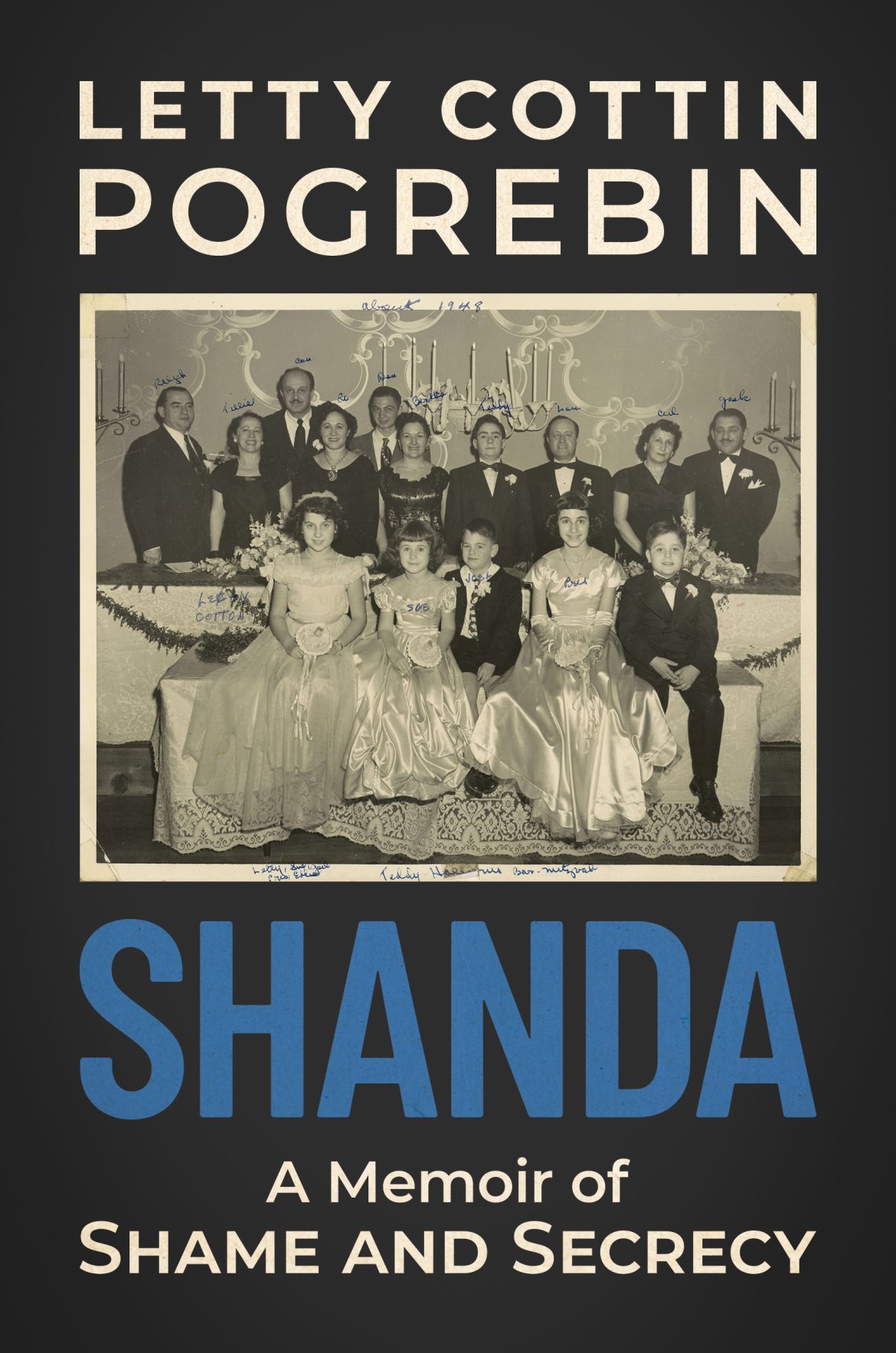

From Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy (c) 2022 Letty Cottin Pogrebin

Published by Post Hill Press. Used with Permission.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin, a writer, social justice activist, and national lecturer, is a founding editor of Ms. magazine, and the author of twelve books. Her works include the feminist classic, Deborah, Golda, and Me: Being Female and Jewish in America, the novel, Single Jewish Male Seeking Soul Mate, and her latest title Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy, to be published this month. (Post Hill Press). She has been a member of Tikkun’s Editorial Advisory board since the magazine’s inception.