My romance with Emmanuel Levinas was something of a whirlwind — short-lived, all in my mind but dramatic, the way such hook-ups tended to be during the shutdown: The pandemic intensified everything, even an unrequited love affair with a deceased philosopher. I preferred to cross it off, to consign the diary I kept to oblivion. But when I came across Reading Levinas and Talmud in a Time of Plague by Steven Shankman, I realized that my springtime entanglement left me with insights into love, loss and Levinas that are worth sharing.

I never expected it to happen. I wasn’t looking for a new relationship, intellectual or otherwise. A neighbor on the Upper West Side left the city for the duration of the pandemic, handing me her keys. A few days later, I retreat to her apartment one flight down, enchanted by her wonderland of plants, books, and CDs. On the first afternoon, my eyes land on a slim volume: Nine Talmudic Readings by Emmanuel Levinas.

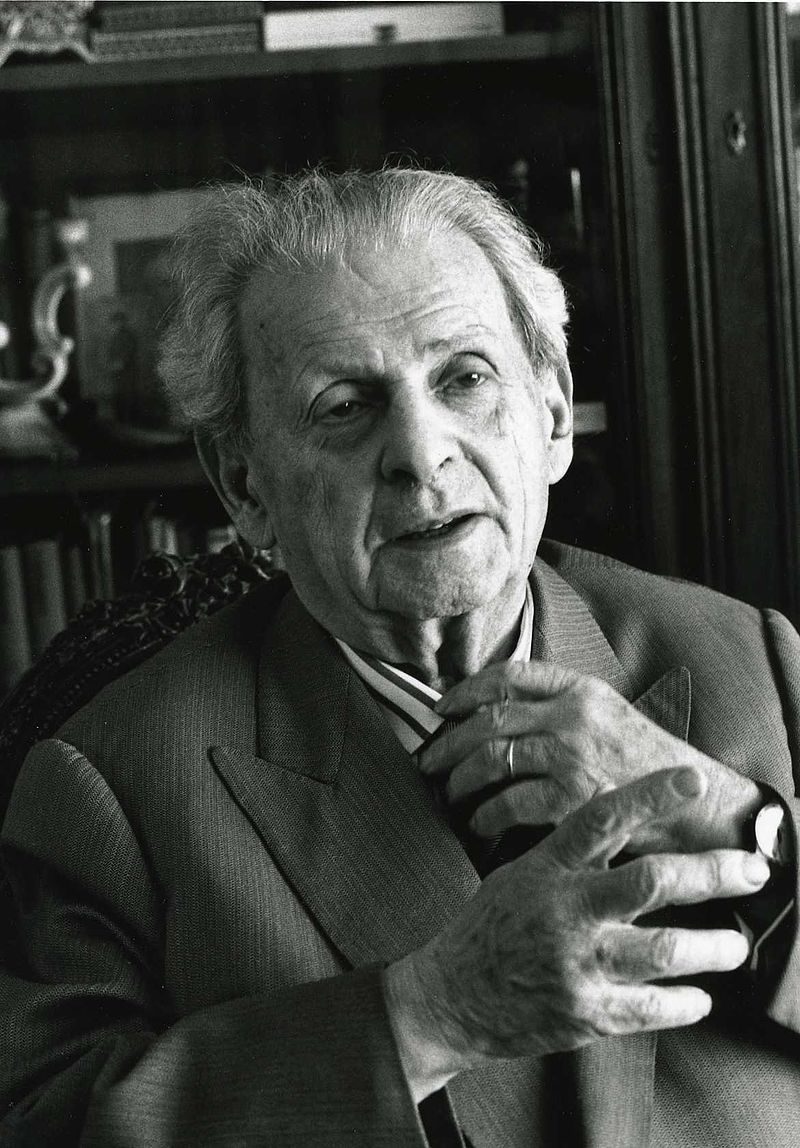

I know just a little about Levinas beyond his towering stature as a 20th-century French Jewish philosopher, a man I assume is too complex for the untutored to decipher. Still, it feels like something larger than myself has brought Levinas to me at this particular time. He is the man with the most to say about our responsibility for the other. Levinas stands out as our most radical ethicist and Covid-19 is screaming that the matter of responsibility for others cannot remain peripheral for another day, maybe not even for another hour. This whole thing has an aura of the bash’ert, the match that is just-in-time and meant-to-be.

I’m not feeling connected, much less essential, bereft of a sense of agency. But in Levinas’ ethics, there are no bystanders, there is only infinite responsibility. The ego, le moi, must turn away from its isolation and its greed. Fifty years ago, Levinas taught that the future of humanity depends on our dedication to caring and connectedness. Suddenly, that life and death urgency is literally true. According to Levinas, there are no boundaries; each of us owes the other all. Isolation Nation …we have all been sent to our rooms to realize how desperately we need a corrective – we sequester because we are inextricably bound one to the other. As I write, a car horn beeps and cooking pots clang. I hear claps and shouts: It’s the 7 PM citywide cheer for those on the front lines. They are essential; I am not at all sure that I am. Still, I rush down to cheer, feeling more connected as soon as I hit the street, with Levinas’ words stirring my heart.

My absentee neighbor is a Ph.D. in clinical psychology, retired now from her analytic practice, a scion of an old Protestant family. So why is her apartment overflowing with books by, and commentaries on, Levinas? She texts me in immediate response to my question: She spent years in a study group led by Dr. Donna Orange deliberating on Levinas’ “achingly rigorous ethical requirements.” For mental health practitioners, Levinas’ standards raised questions about boundaries to be maintained – or not – with their patients. My neighbor goes on to text that “radical Christianity also requires radical unselfishness.” She has always been interested in “how one retains enough of one’s self to give one’s self away,” which is where psychoanalysis might be said to meet Levinasian ethics – and love too, for that matter. The convergence of the unexpected at the right time in the right place has always seemed a prelude to something big, maybe even manifest destiny. Suddenly, my destiny meets Levinas, meets Covid meets love.

But, seriously, what is there between Emmanuel Levinas and me that I should read and fall hard for him? For one thing, I lived more than two decades of my adult life in France, throughout the 80’s and 90’s when, until his death in 1995, Levinas was a prominent Paris-based thinker. On some level we speak one another’s language; this feels promising indeed.

And there are more biographical affinities: The introduction to Nine Talmudic Readings by its translator Annette Aronowicz tells us that during his childhood in Kovno, Lithuania, Emmanuel Levinas, born in 1904, had a thorough religious education. But, for the first part of his adult life in France, his interest in the Jewish sources with which he was well-acquainted in childhood “receded” – as did my own. It was non-Jewish cultural influences that “aroused his passions and commanded his time.” Like Levinas, I spent decades of my adult life in Paris… mundane, multilingual, cosmopolitan spiritual exiles, who, like many Eastern European Jews, were in love with la belle France. Life was good. Style was elevated to a personal creed, the cafes were full, the wine was flowing. We were immersed in what Levinas calls “Greek” civilization, a metaphor he uses for languages and customs Jews have in common with others of the Western world, but which are not specifically Jewish. Greek is the currency of modern times; life was glamorously Greek to me.

With the rise of fascism in the 1930’s Levinas returned to the specificity of Judaism, saying that modern Jewish consciousness should satisfy its “almost instinctive nostalgia for the first, limpid sources of its inspiration.” As for tradition, Levinas would show us “the certitude of its worth, its dignity, its mission.” My return from an expatriate life in France after twenty-two years was a similar reconciliation, a renewal of frayed ties to my profound Jewish roots.

Then there is his interest in the Talmud, a central yet convoluted text that in the past decades has awakened my own passions. In his essay called Temptation of Temptation, Levinas prefaces his work with an apology of sorts. “I am embarrassed that I always comment on the aggadic texts of the Talmud and never venture forth into the Halakhah. But what can I do? The Halakha demands an intellectual muscle that is not given to everyone. I cannot lay claim to it.” For the past decade, I too have become a self-styled student of the Talmud, focusing on the Aggadah or narratives rather than the ‘Halakhah’ or finely-nuanced legal disputes.

Ever humble, in no way comparing my intellect to his, I nonetheless am buoyed by his validation of my own preferences. How reassuring to me that Levinas, like me, finds in Aggadah many opportunities for “us moderns to derive richness from the text.”

I digress for a moment, much as the Talmud does on every page. I am attracted to Levinas not the least for his quirkiness, the way his sort-of-humor is eerily timely. When commenting on an aggadic narrative where a rabbi gets himself in trouble by mouthing off in a tavern, Levinas goes off on a discourse on the dangers of the modern-day equivalent of taverns – or cafes. I come across this on the very day I learn that in a Covid containment measure the French authorities have ordered all the cafes of Paris closed. (This is something that has never happened, not through the whole of World War II). Levinas, for one, would not rue the closing, He writes, “The cafe holds open house, at street level. It is a place of casual social intercourse and no mutual responsibility. One goes in without needing to. One drinks without being thirsty. All because one does not want to stay in one’s room. You know that all evils occur as a result of our incapacity to stay alone in our room.”

Oh, Monsieur Levinas, just look at us now!

If we reframe these restrictions according to Levinas, we are not being punished or even limited; rather, we are being saved from ourselves. Finally, this temptation, these ground level houses of libation and games, places of distraction and dissolution, has, as if by some miracle, itself dissolved. I’ve always been drawn to guys who could work a little spin magic.

So much for our affinities. As with any new and unanticipated romance, soon enough I am challenged by our differences. As I read on, I am made aware that Levinas was a conservative thinker, not a position I share. The nine essays in Talmudic Readings were delivered as lectures at meetings of the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Paris from 1963 to 1975, spanning the great uprising of French students that reached its peak in 1968. But Levinas was never a friend of the excesses of youthful (and to him, reckless) resistance. Unlike his famous Existentialist contemporaries, Sartre, Camus and de Beauvoir, Levinas awards no pride of place to such values as freedom, agency, authenticity. He even finds terms like “dialogue” and “creativity” suspect. In contrast, Levinas finds a text from Sanhedrin in the Talmud reassuring: “There were three rows of students of the Law. They sat before the Judges. Each one knew his place.”

Jagged edges aside, I still find so much that is reassuring in this relationship, or at least I try to convince myself that I do. When Levinas writes of Aggadah that “it contains more than it contains,” but that this textual richness “becomes manifest only when each of us comes to unlock the potential meaning,” he is encouraging me in my nascent endeavor. Along with others, I’ve been going back to Talmud, specifically the Aggadah, and reading through a new, critical lens – that is, from a feminist perspective. I hear in Levinas a posthumous cheer for our seeking against-the-grain meaning, in our venturing beyond the obvious misogyny. I’m thinking with mounting joy that my women colleagues and I will find a champion for our feminist critique in Levinas. My delusional bubble is soon about to be burst.

Turns out, I’m late to the party. There has already been a lot of discussion within academic feminist circles about Levinas’ opposition to gender parity. That’s right. Levinas the radical ethicist is not a believer in gender equality. The face of the other which is the call to the highest impulses in each of us, may well, in his lexicon be feminine. But that does not mean he releases real life women from social oppression. Levinas buys into the male-privileged, hierarchical world of the rabbis and this without apology. I read with deepening shock his commentary on creation: “To create a world, he had to subordinate them, one to the other. There had to be a difference .. and hence a certain preeminence of man, a woman coming later, and as woman, an appendage of the human… Subordination was needed.”

Nor is Levinas free from the Talmudic rabbis’ deep distrust of women. He quotes a rabbinic discussion in which the question is asked: If a man is obliged to walk across a narrow bridge but has a choice to either walk behind a lion or walk behind a woman, which should he choose? Rabbi Johanan says, “It is better to walk behind the lion” and Levinas agrees that the woman poses the greater danger. “To walk behind the lion: to live, struggle, and ambition. To experience all the cruelties of life, always in contact with lions or, at least with human guides, who can suddenly turn around and show you their lion face.”

Even the man who turns on you savagely is a safer bet than the woman. After all, he at least is a human guide !?? But in the woman lies coiled the greater danger of intimacy. For Levinas, like the rabbis, there is no peace in the intimacy of love between a man and a woman. He writes, “The text of the Gemara prefers the danger of the lions to this intimacy. The feminine has been much defended today, as if the relationship with the feminine were only the meeting of the other… What of evasions, of all the ambiguity of the famed love life? What of all the abysses, the betrayals, the perfidiousness, the pettiness?” For once Levinas speaks plainly in a language all can understand. This does little to soften my shock at hearing him cry out in ( to me, the pathetic) tones of the spurned and cowardly courtier.

So then while the shut-down and the pandemic are far from over, for me, the romance with Emmanuel Levinas really is. How can a thinker who worships the feminine as the face of alterity to which we owe our all see no problem in real life women’s subservience to men? Does he not at this point hemorrhage credibility? I dig into the secondary sources, to find that umbrage is not mine alone. Levinas is the first to be criticized by Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex for his allegiance to male privilege as a given. And how to explain it? Doubtless, says she and other feminist critics, it is due to his specific immersion in, and loyalty to, Jewish and Talmudic thought.

I spend the rest of the week pouting, upstairs in my own apartment, without him.

Seclusion’s Conclusions

Levinas knew things needed to be radically different and that the power to change comes not from the top but from the actions of each individual. The resources needed are resilience, empathy, generosity, connectivity, selflessness,. These are all qualities which those who today persist in seeing gender-based differences, most often assigned to the feminine. As feminists we meet Levinas in that place of prioritized values even if his gender bias did not free him to see women in the front lines of radical change.

Looking back, je ne regrette rien. I learned a lot from my temporary enchantment with the great if flawed philosopher.. As a woman engaged with my Jewish heritage ( and ipso facto with men), I’m accustomed to the effrontery, the jagged edges, the impossibility of total harmony. As a woman who is drawn to the Talmud I am more than accustomed to unrequited love, to being seen, even by otherwise perceptive men, not as I am but as they fear me to be. I like to cultivate a certain generosity of spirit: If Levinas had lived beyond 1995 I think by now, he would have evolved so as to no longer consign one gender to subservience.

Levinas emphasized Judaism as a source of ethical inspiration; his work does re-affirm “our tradition’s worth, its dignity, its mission.” By now we expect to find radically ethical values in our texts right alongside sexist ( and other forms of bigoted) slander. We all live better once we accept this historical paradox. I will work on my own narcissistic injury in order to keep benefiting from his wisdom. Love, as we adults must know by now, is rarely a perfect fit.

Months into the pandemic which is only growing more virulent it still feels like a larger destiny is invading our lives along with a microscopic killer. My experience with love and loss and Levinas is an invitation to an urgent understanding of what that might mean.