On November 19th, three of us: Emma Quayle, Erin Mychele, and myself, embarked on a journey to a remote part of the California desert for four weeks of what I envisioned would be a restful, relaxing time enjoying the natural hot springs present there. I was longing for a spiritual reset, a way to shift my deeply ingrained patterns that keep my body over-producing cortisol. My friends joined in part in support of their own quests and in part to be with me in mine, entrusting themselves to my stories about the place, where I had been many times between 1989 and 2004.

On November 19th, three of us: Emma Quayle, Erin Mychele, and myself, embarked on a journey to a remote part of the California desert for four weeks of what I envisioned would be a restful, relaxing time enjoying the natural hot springs present there. I was longing for a spiritual reset, a way to shift my deeply ingrained patterns that keep my body over-producing cortisol. My friends joined in part in support of their own quests and in part to be with me in mine, entrusting themselves to my stories about the place, where I had been many times between 1989 and 2004.

This time turned into one of the highlights of my whole life so far, and similarly for my friends. The path there bore no resemblance to what we imagined would happen, and the result was love beyond measure, clarity of purpose, individually and collectively, and significant visceral and conceptual understanding about what it takes to break free, individually and collectively (in small groups, at least), from our patriarchal predicament.

The path included very difficult physical conditions and hefty relational challenges. We persevered, in a flash flood, in a leaking tent, in the cold, in the conflict, in everything, through a profound commitment to liberation and truth. There were several days, especially in the earlier part, in which I really wanted to get out of there. I wanted rest, and instead experienced hard work; I wanted peace, and was instead part of a lot of conflict; I wanted relief from responsibility, and instead needed to mobilize, repeatedly, in support of our threesome. Part of what kept us at it was the simple fact that it wasn’t possible to exit and we depended on each other for our very basic survival. With each new challenge, we learned how to be together. With each conflict, we modified our agreements to support our capacity. We held back less and less over time, and finally when it came time to go back, at least part of each of us didn’t want to part ways.

The path included very difficult physical conditions and hefty relational challenges. We persevered, in a flash flood, in a leaking tent, in the cold, in the conflict, in everything, through a profound commitment to liberation and truth. There were several days, especially in the earlier part, in which I really wanted to get out of there. I wanted rest, and instead experienced hard work; I wanted peace, and was instead part of a lot of conflict; I wanted relief from responsibility, and instead needed to mobilize, repeatedly, in support of our threesome. Part of what kept us at it was the simple fact that it wasn’t possible to exit and we depended on each other for our very basic survival. With each new challenge, we learned how to be together. With each conflict, we modified our agreements to support our capacity. We held back less and less over time, and finally when it came time to go back, at least part of each of us didn’t want to part ways.

We were deeply conscious, all along, of wanting to learn and then share with others what we learned. We documented everything we did, and then put it all together in a document that we agreed to share with anyone who is interested. It includes our purpose, the mission that we embraced to accomplish the purpose, our theory of change that grounded our trust that our mission would support the purpose, and the agreements that we came up with and continued to refine till after the last day. It also includes principles we extracted from our experience that we believe can support others, in whatever configurations, in establishing their own ways of functioning if they have a similar kind of purpose. This post is, in some ways, a guide to reading that document. Given the intensity and depth of the experience we had, this post is by necessity cherry picking, focusing on some parts of what we did while ignoring others. The way I chose what to focus on is based on an intuitive sense of what would be most likely to contribute to others and be understandable enough in written form without going through the experience with us.

What I am completely leaving out is all the personal experience of being in that desert; all the breathtaking beauty (some of which is at least included in pictures); the thrill of adventure and the sheer fun of so many moments; and, overall, just what it was like to be there, to experience all of it, both what I am sharing below, and what I’m not.

What I am completely leaving out is all the personal experience of being in that desert; all the breathtaking beauty (some of which is at least included in pictures); the thrill of adventure and the sheer fun of so many moments; and, overall, just what it was like to be there, to experience all of it, both what I am sharing below, and what I’m not.

Basic Framework: A Systemic Response

Two of us came into this experience with full clarity that in order to function well we would need to have clear agreements about how we wanted to function, and the third one was willing to engage in this way based on trust and without really knowing what we meant by agreements. And it was a big learning experience, both for her and for the rest of us.

We started out with a very minimal set of agreements that came from an earlier time when we were all together, inspired by Uma Lo: that we would check in each morning to review and modify whatever agreements we have, and that, over dinner, we would share information with each other about any negative impacts we experienced that day as a result of something any of us did. As we started meeting each morning – for many hours in the first few days, gradually diminishing to less than 45 minutes – we expanded the container to include a purpose, a mission, and a theory of change. For our values, we used the existing ones from NGL, to which we have some proposed changes I document further below. Our agreements, and everything in our containers, evolved organically through trial and error. Every conflict, every misunderstanding, every lapse in function, and every challenge led to looking at our agreements freshly and enhancing them. This was the key to all: looking at things from a systemic perspective means that anything that doesn’t work would be seen as a hole in our container rather than as individual dysfunction. Instead of implicitly or explicitly waiting for any of us to magically change or heal individually, we looked for what we can do collectively to provide sufficient support that will create conditions for all of us to thrive. Although this approach is not new to us, this is the furthest we’ve ever applied it, and we now have a visceral sense of how much a systemic, support-based response to challenges is necessary in these times of global crisis, as individual changes are far too slow and resource-intensive to make a dent fast enough.

Purpose: an Algorithm to Prioritize Needs

We had our first draft of purpose within one day. Given our commitment to liberation from patriarchy, we started out with a purpose that was focused on transcending scarcity, separation, and powerlessness, the core pillars of patriarchy as we see it. We then added what we wanted to reach, and eventually left only that within the purpose. At that time, the purpose read: “to restore in full our individual and collective capacity to live from choice, togetherness, and flow.” Over time, and especially as we started to support each other in coming up with our individual purpose statements for our respective lives, we came to recognize that this is an overarching purpose for anyone who wants to align in this direction through this lens, and that there was something specific and unique about our purpose for while we were together and in the desert. From this, we came to understand that a useful purpose statement within this framework would be one that points to the specific gifts, attributes, and context that the purpose emerges from and speaks to. At that time, it became absolutely clear what our purpose would then be. Here is the final statement that we arrived at:

To mobilize our dedication to purpose and to one another, and our willingness to surrender to the desert under all f^&*ing conditions, to restore in full our individual and collective capacity to live in choice, togetherness, and flow.

Here, below, is my own purpose that I articulated while there, which I share here in support of clarity about how varied such purpose statements can be:

To mobilize my conceptual clarity and commitment to nonviolence to share with others what I learn about what it takes, in a time of global crisis, to restore in full our individual and collective capacity to live in choice, togetherness, and flow.

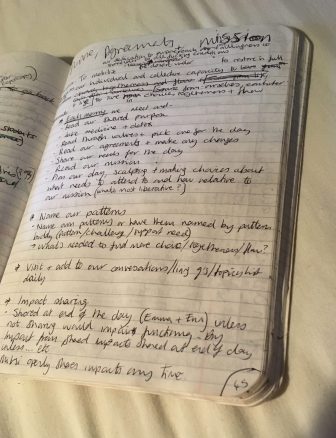

A page from Emma’s notebook, where we kept notes, taking it to all of our meetings, including when we met in the hot springs!

The same configuration of people coming together for a different purpose would do different things. When purpose is made front and central, it becomes a tool for making decisions, and, most especially, for prioritizing which needs to put on the table and how to integrate various desires into one plan that works for everyone.

Even within the same purpose, focusing on different aspects of the mission would yield different results. For example, one of the elements of our mission was “to learn from everything that happens between us.” For the first while, this was almost all we did. Later, this aspect of the mission became less central, and this changed our way of planning and thinking about which needs to bring to our planning time and how to attend to them. Eventually, we let go of this aspect altogether as we wanted to attend to other ones, and learning from everything is a really huge commitment. Our current intuition is that any group that aims to come together with an intention of full liberation will need some period of time to engage in this kind of deep, intensive way, and not forever.

Values: How We Approach What We Do

We decided right from the start that we would use the set of values that have been supporting the Nonviolent Global Liberation community. We quickly agreed to pick a value each morning to guide our actions and ways of being that day, and to evaluate how we managed with the value by the end of the day. Like all decisions, we made the choice about value intuitive and consensual. We were only three people, with liberation being our primary focus, and thus aiming for consensus, including the risk that it would be a huge investment of energy, made sense to us.

NGL currently has a list of thirteen values, and we are proposing to add three more. Even before the additions, that’s a lot of values to hold. One of the core insights that NGL is based on is precisely that values that aren’t anchored in specific agreements that form systems are less likely to influence behavior: an intention is not strong enough to provide an antidote to a habit or pattern. Patriarchy has instilled in us a set of habits and patterns that are based on its core values, which rest on scarcity, separation, and powerlessness, and focus on mechanisms of control, either/or, right/wrong thinking, and motivation by fear, shame, obligation, or, conversely, impulse. Those are deeply ingrained and upheld by societal agreements, both laws and norms, which reinforce them. Just naming, for example, that “only that happens for which there is wholehearted willingness and availability” will not, by itself, change people’s patterns of overdoing or underdoing. Rather, for this kind of change, mechanisms are needed that regularly check if anyone has stepped out of this value, as well as specific agreements put in place tailored to specific groups or individuals where active support is needed and sought in order to counter the weight of patriarchy.

Given all this, choosing only one value a day supported us, both in terms of being able to focus, and in terms of noticing what was missing from our agreements and what we might want to add or refine for our next day.

Needs, Impacts, and Resources

In the last several months, I have been focusing on a simple framework that I have found extremely helpful: that when all the known needs, all the known impacts (including anticipated ones), and all the known available resources are put on the table, decisions about what to do can be made with much simplicity and clarity. Unfortunately, one of the results of living in patriarchal societies is pervasive mistrust and lack of skill in working out differences, both of which lead to immense difficulties in having this information. As an oversimplification, under conditions of patriarchy we are likely to put shoulds and concepts on the table instead of needs; shame and blame instead of impacts; and patterns of scarcity instead of clarity about available resources. In some ways it’s fruitful, within this framework, to see the work that people like me do as removing the obstacles to having all this information on the table, available to make decisions with.

At this desert retreat, without initially taking on this framework explicitly, we discovered that we were effectively doing precisely this. We shared impacts, in a level of truth in sharing and lack of defensiveness in receiving that moved each of us to tears in different moments. There was nothing easy about it. Each of us, in different moments, was invited to confront our own limitations in being able to engage in this way. Multiple times things broke down temporarily.  Having no exit created an external insistence on togetherness that is sorely missing in our modern, individualized, fast-paced lives, full of so many more options than are truly needed. We discovered, to our amazement, that having fewer options supports more freedom and choice. Every breakdown eventually led to greater clarity, revised agreements, and more love. Eventually, we added a line to our mission to capture the depth of our spontaneous process: “To discover and transform limitations to sourcing from ourselves, each other, and life.”

Having no exit created an external insistence on togetherness that is sorely missing in our modern, individualized, fast-paced lives, full of so many more options than are truly needed. We discovered, to our amazement, that having fewer options supports more freedom and choice. Every breakdown eventually led to greater clarity, revised agreements, and more love. Eventually, we added a line to our mission to capture the depth of our spontaneous process: “To discover and transform limitations to sourcing from ourselves, each other, and life.”

I learned, for example, that, in just about all circumstances, I automatically focus on integration and convergence. We named me, semi-facetiously, a togetherness engineer. It’s often very helpful to the whole, and yet I have not been fully enough conscious of what I do, and thus have not been transparent about it. The result is that the work I am doing, the care that goes into it, and the cost to me, all remain invisible. Neither my needs nor my stretching are seen and known. My own needs are not seen because I adapt my strategies without naming my preferences more often than not. At the same time, because I don’t say what I am doing, it appears to others, more often that serves anyone, that I am only advocating for what I want, because I integrate so seamlessly.

In part to counteract the invisibility of impacts on me from this extra work I do, we had an unequal and “unfair” agreement for most of our time: the other two, Emma and Erin, would be sharing impacts on them only at dinner time, unless withholding impacts until then would compromise our capacity to function as a whole; while I was invited, encouraged, and supported to share impacts on me at all times, in their full intensity, even when it was beyond Emma or Erin’s capacity to take in. They still encouraged me. Sure, it was messy. And, nonetheless, it was transformative at a time when I was focusing on liberating myself from the extreme extra work I’ve been doing for so many years. Eventually, as we built individual and collective capacity, we were able to share more and more impacts with more and more capacity to hear them. In parallel, we also focused on sharing impacts in a way that would be most conducive to others being able to hear them, in full self-responsibility, without blame, shame, or subtle criticism; only impact, not assessment of the other person. My sense is that our collective willingness to share and hear impacts is the single factor that most got us to this place of immense love. Whenever we don’t share impacts – which is most of the time for most of us given the level of mistrust and separation that exists in our cultures – it limits closeness.

We also discovered the cost of not putting needs on the table at the time, during our morning  meeting, when we were making the plan for the day. The set of activities possible in the desert when we were there was super limited: eat, sleep, walk, soak, talk, cook, make tea, clean up, read, go to the toilet. Not all of them could be done at all times, as it was sometimes too cold to sit and talk or read. So planning was basic, and, still, we wanted our planning to include as many as possible of our individual needs, collective needs, and purpose-related needs. Not including them, for any of us, meant that later in the day things wouldn’t work for one or more of us, and unexpected impacts would ensue. This was the point, one day, after one more breakdown, where we realized that the depth of our respective patterns of not putting our needs on the table was such that any agreement to include all of our needs could not be legislated. The change in agreements had to happen at another part of the day. And so we came up with an agreement that exposed the impacts of not sharing needs and thus increased the motivation to create inner shifts. The agreement was one that I wish all groups to have: that anything that wasn’t included in a decision made or a plan created and showed up later would be brought up at a different threshold. The preferred solution would be for that person to absorb the impact on them. If that wasn’t accessible to them, the second option would be to check to see if there is low to no impact on others, and only create a change if the impact was within those parameters. And, of course, being humans and thus always having choice, if the need to create change in a plan was that significant, the last option would be to make the change and take responsibility for the consequences. The only thing that we ruled out, in effect, is the kind of magical thinking we so often want to hold on to: that we can change our minds about something and have no impact on others as a result.

meeting, when we were making the plan for the day. The set of activities possible in the desert when we were there was super limited: eat, sleep, walk, soak, talk, cook, make tea, clean up, read, go to the toilet. Not all of them could be done at all times, as it was sometimes too cold to sit and talk or read. So planning was basic, and, still, we wanted our planning to include as many as possible of our individual needs, collective needs, and purpose-related needs. Not including them, for any of us, meant that later in the day things wouldn’t work for one or more of us, and unexpected impacts would ensue. This was the point, one day, after one more breakdown, where we realized that the depth of our respective patterns of not putting our needs on the table was such that any agreement to include all of our needs could not be legislated. The change in agreements had to happen at another part of the day. And so we came up with an agreement that exposed the impacts of not sharing needs and thus increased the motivation to create inner shifts. The agreement was one that I wish all groups to have: that anything that wasn’t included in a decision made or a plan created and showed up later would be brought up at a different threshold. The preferred solution would be for that person to absorb the impact on them. If that wasn’t accessible to them, the second option would be to check to see if there is low to no impact on others, and only create a change if the impact was within those parameters. And, of course, being humans and thus always having choice, if the need to create change in a plan was that significant, the last option would be to make the change and take responsibility for the consequences. The only thing that we ruled out, in effect, is the kind of magical thinking we so often want to hold on to: that we can change our minds about something and have no impact on others as a result.

Over our weeks in the desert, on the other side of our many challenges, we got into more and more capacity to engage with ourselves, each other, and life, from precisely that elusive intersection of choice, togetherness, and flow that we sought to reach. Our flow was interrupted less and less often; when our togetherness broke down, we repaired it more easily; and we experienced full choice in how we responded to life and to each other more of the time.

Mindful Consumption

Our weakest link in our mission was the item we called mindful consumption. Given we were in a really remote place (several hours on a dirt road and through mountain passes to the next place) and without electricity for so long, we needed to bring with us all the food we would consume for the entire time. This meant almost no fresh food. Thanks to the availability of veggie powders and freeze dried food, we were able to have enough vegetables and fruits for our nutritional needs. The main challenge was snacking, not meals. While we managed to have a number of deep and meaningful conversations, and touch the vulnerability of our collective addictions to comfort, to taste, to ease, and to self-soothing through food, we didn’t manage to shift our actual habits in any significant way. In the end, when we looked at our mission, we noticed that the line about conscious consumption was the only one that didn’t have a verb at the beginning, and we wondered whether there was any connection between that and the fact that the agreement about snacking was the one we rarely kept. Our conclusion is that anchoring that commitment in actual agreements that would create shifts in behavior would take more than we did. Had we stayed longer in the desert, this would have been our next area to look even more deeply into to come up with more robust and capacity-based agreements; the one we had was simply too aspirational.

Lessons for Other Contexts?

Clearly, the circumstances we were in and co-created with each other were unique and the specific agreements we created would not be useful for most other situations except for ones in which a small group of people comes together for a similar kind of what we have now come to call a “liberation retreat.” Even for the two of us who are still together, in a new setting, these agreements are no longer useful, and we are working quite diligently to create a new container for the new circumstances. Still, one of our mission elements was precisely about identifying replicable principles, and we succeeded in identifying over thirty principles that we believe could apply to any group of people that are aiming to function in ways that are significantly different from the mainstream, patriarchal cultures in which we live. The document includes all of them, and here I want to highlight just a few.

Robust Conflict Systems

We knew that we needed to have agreements about what we do about conflict. We didn’t make these agreements right away, as some of us teach others to do! We waited until we had a conflict significant enough that our existing agreements didn’t hold it, and then we added an agreement about conflict. Even then, we didn’t keep the entire agreement, most especially we forgot to check regularly if there was any conflict open somewhere among us. As we reflected on it, this is likely to be the case for many groups in patriarchal societies. Conflict, as I understand it, arises from a tear in togetherness. It requires, therefore, even more togetherness to attend to it. That is a particularly big stretch for the parties most directly involved, because we tend to be immersed in our own experience of any conflict we are part of. This is precisely why a robust system is needed, including active scouting to identify conflicts and activate the system. The larger the group, the more important it’s likely to be to have the system come toward the people rather than expecting individuals to transcend patterns of conflict avoidance and initiate it.

Transitions

Panoramic view as we were driving in

Whatever the setting, whoever the people are, and whatever the purpose and values, transitions are the moments in which agreements are most at risk. In moments of transitions, whatever flow exists based on whatever agreements are in place is interrupted, and new decisions need to be made to attend to the transition. Without active, tender, and conscious engagement, we are more vulnerable, during transitions, to revert to unconscious habits simply to manage the various reactions we have to change and shifts. This is especially true if the transition is external, such as the many times we end things based on specific time agreements, and not organic, when an activity ends when it’s clear that it’s over. We learned through our experience that, during transitions, slowing down and bringing conscious choice and togetherness to the process of transitioning and to the inevitable new decisions that then arise will often result in renewed flow.

Capacity

I want to conclude this post with what I already alluded to before: the more we are rigorous about creating agreements that are based on true capacity rather than what we wish were true, the more likely it is that such agreements will be kept. This is a rigorous practice because we are deeply habituated to think of agreements as “rules” that “must” be followed, and we are trained to hide places where our capacity may be compromised. The result is often agreements that will be broken regularly, because, if we can’t do something, we won’t, no matter how much we tell ourselves that we should do it, and no matter how much we tell others that we will. This, in times of great peril, is a key principle to remember. So much energy is lost because we make aspirational agreements and then use them as weapons against each other when they are broken. There is tenderness in investigating and accepting where our true capacity is as well as that of others. And in updating this as things change, discovering what actual capacity we have in these new circumstances, and, based on that, what agreements would actually work (questions that the two of us who are still together now are quite actively grappling with now).

We know this and are aiming to apply it: When all of us can hold with tenderness that all of us will have limited capacity under conditions of patriarchy and that these are collective challenges, not individual deficiencies, we will be able to make agreements that attend to systemic lack of capacity, and that therefore are more possible to keep. Then, as if by magic, the keeping of the agreements, in itself, becomes a path to building capacity within the group, and over time our agreements can become more and more aligned with the world and life we want to create.

Photo Credits: First, Second, Third and Sixth by Vance Selover; Fourth, Fifth and Seventh by Emma Quayle