Everyone, especially the most vulnerable among us, requires assistance and has the right to have access to necessary care. This is even more evident in these times when all of us are called to combat the pandemic, and vaccines are an essential tool in this fight. In the spirit that the vaccine should be international, in a spirit of global responsibility, [I call on us] to commit to overcoming delays in the distribution of vaccines and to facilitate their distribution, especially in the poorest countries.

I understand him very well, not just because we were both born, raised, and walked the same streets of Buenos Aires in Argentina and have witnessed the same inequities. The pope’s words resonate with me because these scandalous differences become more visible every day when those who are suffering and dying because of COVID-19 in countries like mine, with fewer economic resources, could be saved if vaccines arrived on

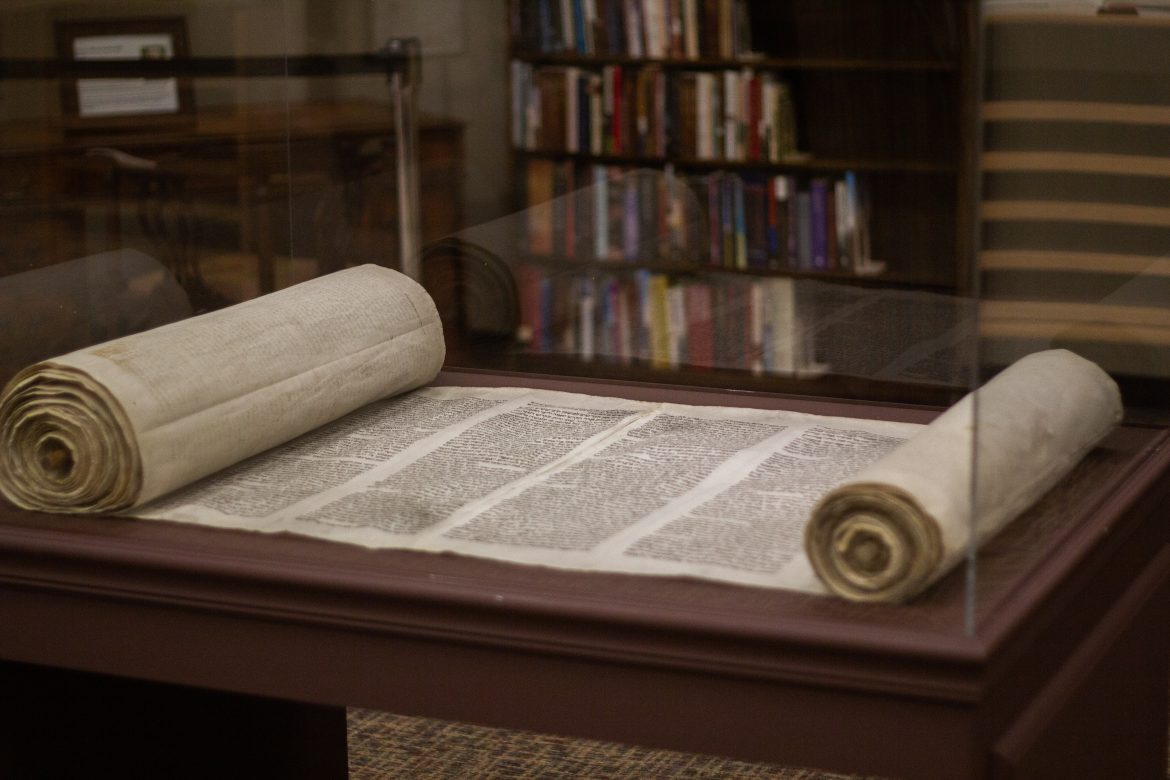

This week’s Torah reading of Parshat Kedoshim questions us about our human relationships, how we treat our siblings, and how we relate to our neighbors to make this world a better place to live. So here I go back to the beginning. When I read in Kedoshim, “Do not stand before the blood of your neighbor” (Leviticus 19:16), I feel the moral obligation to shout that it is not nationality that makes a life something sacred and that we have the responsibility to watch over our neighbors. Each and every one of them. “Kol Israel arevim ze bazé.” All Jews are responsible for each other, say the sages of the Talmud in Shevuot 39a. And in the words of Emmanuel Levinas, we are all infinitely responsible for each other. That means that once we see their face, their need and humanity, we can’t turn our eyes the other way.

A few days ago I read a tweet that said “We are all in the same storm but not in the same boat.” This, I think, is meant to be a critique of the common expression, “We’re all in the same boat,” but to me the rebuttal misses the point in both directions. I cannot conceive a humanity that does not believe that it has a common destiny. The ship is one and this is how the rabbis of our Midrash teach us:

Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai taught a parable: Men were on a ship. One of them took a drill and started drilling underneath him. The others said to him: What are you doing?! He replied: What do you care? Is this not underneath my area that I am drilling?! They said to him: But the water will rise and flood us all on this ship. (Leviticus Rabbah 4:6)

But it’s not just that. In addition to the fact that the ship is one, there are those who are not even inside it, but are floating adrift.

It is a harsh image that goes beyond a metaphor. We have seen thousands drowned in the sea trying to reach more prosperous places to have a better life and future. We don’t even make room for them on the boat.

Kedoshim means holiness. It is not an acquired right but an aspiration, a place to reach. “Kedoshim tihiyu,” says God, using the future tense; not “Kedoshim atem,” stating a present condition.

This challenging time calls us to recover the project of humanity that we seem to have lost.

This article appeared first on T’ruah the rabbinic call for human rights.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.