[Editor’s Note: Tikkun hopes to support all the different religious and spiritual communities of our world, even while critiquing the extent to any one of them is distorted to the extent that it has been influenced by racism, sexism, homophobia, antisemitism, or any other form of nationalism and triumphalism. While many of us have been influenced by our experiences in one or another Jewish path, or by Jewish Atheism or Agnosticism, we all have faced the need to challenge some aspects of our tradition.

– Rabbi Michael Lerner, Editor of Tikkun and author of the national best-seller, Jewish Renewal: A Past to Healing and Transformation, published by Harper.]

Jewish Injustice

On the Role of Women Witnesses

By Rena Beatrice Goldstein

“We have to question the intentions of any group that insists on disdain toward other people as a membership requirement. It may be disguised as belonging, but real belonging doesn’t necessitate disdain.”

“Religion is another example of social contract disengagement. First, disengagement is often the result of leaders not living by the same values they’re preaching. Second, in an uncertain world, we often feel desperate for absolutes. It’s the human response to fear.”

– Brené Brown, Daring Greatly: How the Courage To Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead

A friend of mine (I’ll call her Rebecca) is getting married. She asked me a year before her wedding to sign her ketubah (in Hebrew כתובה; Jewish marriage contract) as a witness. Three weeks before her wedding, Rebecca calls. My signature, she explains, cannot validate the marriage because I am a woman. Some Orthodox and Conservative sects of Judaism do not validate ketubot signed by women witnesses. Rebecca wants her child(ren) to have the option to become orthodox if they choose. She does not want any doubt about the legitimacy of her marriage.

Rebecca apologizes for the change in plan. I was gracious on the phone, kindly reassuring her that I understood. I’ll be honest, though, I felt sad. Rebecca decided to follow the law: only men’s signatures legitimize a marriage contract. Rebecca and her fiancé (whom I’ll call Isaac), a soon-to-be Rabbi, are supporting a negative view about the reliability of women’s testimony. In other words, this law is a call back to a time when women were not considered reliable testifiers. As a philosopher who writes on testimonial injustices, how could I possibly support her? I am troubled by such thinking.

From Rebecca’s perspective, she wants her children to have all the opportunities available to them in the Jewish community—any Jewish community—that they may wish to one day embrace. This means that their marriage, and hence the ketubah, must be beyond reproach. Some couples choose to have two separate ketubahs, but Rebecca and Isaac were sensitive to legal questions about the validity of the ketubah. Given the constraints, Rebecca’s decision is understandable. She is thinking about what’s in the best interest of her future child(ren).

I am aware that those who subscribe to the orthodox position rely on rabbinic sources to justify interpretations of the law. Maimonides, for instance, argued that the exclusion of women is justified on the basis that the Torah refers to witnesses using masculine language. For this reason (amongst others I’ll discuss later) women are not qualified to serve as witnesses. Rabbi Susan Grossman (2004), on the other hand, has questioned whether prohibition of women testifiers falls under “gezerart HaMelech, [or] an immutable command from God our sovereign” (p. 2). That is, the prohibitions of women testifiers come from the best effort of the sages to understand God’s will as expressed in the Torah. Some contend that the sage’s interpretations occur within a specific social-political climate that must be taken into account. The orthodoxy tends to leave aside the lived experience of Toraitic sources. While I do not agree with it, I understand that excluding women as a witness (even in limited cases like that of capital punishment) is a hermeneutical position taken by the orthodox.

Should modern Toraitic interpretations account for past social-political climates? If so, then to what extent? It is this question that Conservative Rabbis must always contend. This question gives rise to a dichotomy between changing practice to meet modern social norms and adhering to traditional biblical interpretations. As Rabbi Grossman writes, “the Conservative Movement is built upon the balance between tradition and change” (p. 11).

Some Conservative Rabbis also adhere to the orthodox hermeneutical position. This means that they take the interpretations settled in the Mishna or the Talmud as the law. Maimonides argued that women are to be excluded as witnesses. Therefore, women are not to be witnesses. Other Conservative Rabbis may not adhere to the orthodox hermeneutical position, but they might have justifiable reasons for maintaining such legal practices. Some might recommend adherence to such legal practices in effort to protect their congregants. In the case of the ketubah, there could be consequences if a ketubah is not in keeping with standard practices: it may not be considered valid. A Conservative Rabbi suggesting only men sign ketubot as witnesses may not agree with the legal practice but may recommend it given the current social-political realities.

For context, Rebecca and I grew up in the Conservative Jewish movement. My upbringing straddled both the Jewish community of Las Vegas and Los Angeles, while Rebecca grew up in Los Angeles. We met after Bat Mitzvah age (14-15 years old), attended weekend programs during the school year with United Synagogue Youth (a Conservative Jewish youth group), and spent summers together at Camp JCA Shalom (a non-denominational Jewish summer camp in Malibu, California). Isaac did not grow up in Los Angeles but moved here when he began the rabbinical program at the American Jewish University in Los Angeles.

Growing up as a woman in the Conservative Jewish movement in the western United States has been challenging. Without question, there has been progress for women’s inclusion in ceremonial rituals. I had a Bat Mitzvah, though many of my mother’s generation did not. I can sit with the men in a Conservative synagogue during services. I went to Hebrew School, and my father studied Torah with me every Saturday. I am educated. I can read and write Hebrew. These are just some of the equitable changes which have been made in the Conservative Jewish movement to more justly incorporate women.

In the Conservative movement, I’m constantly coming up against an invisible barrier. For instance, my father is a Kohen ( ןֵהֹּכ ; priest), but I can’t inherit the Kohen bloodline or participate in the high holiday ritual blessing. I don’t count in a minyon ( ןָיְנִ מ ; minimum number required for collective prayer). In my synagogue, it was never a requirement for a woman to wear a kippa ( הָיפִ כ ; head covering) or tallit (יתִ לַט ; prayer shawl), yet for my brother it was. My brother was gifted t’fillin (יןִ לִ פְּ ת; two square boxes with scriptural passages worn on the forehand and the left arm) at his Bar Mitzvah, though my sisters and I never were. These are just some of the traditional rites in which women are still not fully equal; the exclusion is subtle. Not everyone thinks that these practices (like it being optional for women to wear kippot in shul) are exclusionary. Yet the optionality of some ritual practices signals women are less important than men. It signals women are still second class.

I am going to point to one more subtle exclusion, one more invisible barrier: the qualifications of being a witness. Considerable attention has been paid to the ketubah as contractual document in Jewish theology. You can find books written on its history, and articles on how to rephrase the sexist, archaic language for the modern age. But little attention has been paid to the gendered role of the witness, a role that still to this day excludes women from the practice. For the remainder of the article, I discuss the role of the witness, specifically the role that men occupy and the rule by which women are excluded. I will argue that Rabbis in the Conservative movement ought to solidify their stance on the role that women have in religious ceremonial practices, specifically the practice of witnessing signings of ketubot. I suggest that Rabbis should base the qualification for being a witness on values rather than biology.

Witnesses of the Ketubah

Ketubah (כתובה) translates to “written instrument” (Epstein 2004, p. 4). As is to be expected, there are debates as to the historical origin of the ketubah. Some believe the ketubah was identical to the Shetar Kiddushin and is thus the oldest marriage contract. While others argue that the two are not the same, and indeed the Shetar is older, with the ketubah having been instituted as a reform to the Shetar (Zeitlin 1933, p. 2). Similarly, there are debates over whether the ketubah validated a marriage (that is, consummated it) or merely recorded the obligations of the husband as a legal protection for the bride (Epstein 2004, p. 5-6). Louis Epstein argues that (at least part of the purpose of) the ketubah was to make sure the groom could not put off marriage or easily divorce if he grew tired of her (2004, pgs. 20-24). It eventually became practice that the ketubah be in the safekeeping of the bride.

Whatever its historical origin, we know today that in the western United States, in the Conservative Jewish movement the role of the ketubah is merely ceremonial. It does not consummate marriages, for those betrothed must still obtain a marriage license from the secular county. Epstein (2004, p. 31) argues that the adoption of the ketubah, and other writs by the Jewish people developed due to secular economic interests. He notes from the lack of reference to a ketubah between such biblical figures as Rebecca and Isaac, Jacob and Leah, Jacob and Rachel, and Ruth and Boaz the ketubah is not an original Jewish institution but is, in fact, originally an institution of Babylonia. Contact between Babylonia and Judea introduced the writ to the Jewish people. Today, language is generalized, the typeface stylized. It does not have the same purpose as a writ of acquisition.

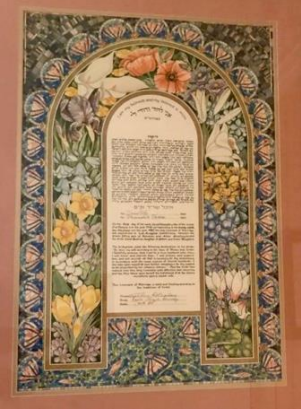

What does the ketubah look like today? Above is the stylized, embellished ketubah of my Sephardic grandparents, Silvy and Carol Alcalay, married in 1953 at the Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel in Los Angeles, California.

It reads:

On the first day of the week, the fifteenth day of the month of Tamuz in the year 5713 corresponding to the twenty-eighth day of June in the year 1953 the holy Covenant of Marriage was entered into in Los Angeles, California between the groom Silvy son of Solomon and Alice Alcalay and the bride Carol Beatrice daughter of Albert and Irene Rugeti.

The bridegroom made the following declaration to his bride: “Be thou, my wife, according to the laws of Moses and Israel. I faithfully promise that I will be a true husband unto thee; I will honor and cherish thee; I will protect and support thee, and will provide all that is necessary for thy sustenance in accordance with the usual custom of Jewish husbands. I also take upon myself all such further obligations for thy support as are prescribed by our religious statues.” And the bride has entered into this holy Covenant with affection and sincerity and has thus taken upon herself the fulfillment of all the duties incumbent upon a Jewish wife.

This Covenant of Marriage is valid and binding according to the tradition of Israel.

This ketubah was witnessed by Samuel Toby and Morris N. Tarica and signed by the groom, the bride, and the Rabbi, Jacob Ott.

What does it take to validate a ketubah? In the mishna it states that the contract is valid on the basis of two witnesses (Gittin 22b).

ר’ אלעזר היא דאמר עדי מסירה כרתי

Here are some translations:

Whosoever killeth any nefesh, the rotze’ach shall be put to death by the mouth of edim (witnesses); but ed echad (one witness) shall not testify against any nefesh to cause him to die. (Bamidbar 35:30).

One witness alone will not be sufficient to convict a person of any offense or sin of any kind; the matter will be established only if there are two or three witnesses testifying against him. (Deuteronomy 19:14-16).

One witness shall not rise up against a man for any iniquity or for any sin, in any sin that he sinneth. By the mouth of two witnesses or by the mouth of three witnesses shall the matter be established (Deuteronomy 19:14-16).

According to Deuteronomy 19:14-16, two witnesses are required to validate ketubot. The classical ketubah is the document conveying the testimony of the two witnesses only. It required their signatures. Not that of groom or bride. Only in the current moment have some included the couple’s signature. The signatures of the witnesses establish that two people saw the same thing. One person can perhaps be bribed or mistaken. But if two people witness the signing of a contract, there is good reason to believe that the contract was signed under appropriate conditions.

Historically, the signing of ketubot was not ceremonial. It was a contract between families. In biblical times, the presence of a Rabbi was not required. Required were two literate witnesses. But we have developed traditions that have been cemented into practice. Indeed, in the mishna it states, “only priests, levites, and those who intermarried with priests signed ketubot” (mishna, as cited by Episten 2004, p. 48). Priests and levites held positions that required literacy. Today, in our vastly more literate society, the qualifications of being a witness vary significantly, largely depending on the interpretation of the law agreed to in of each Jewish denomination.

The reform movement was created to ensure that laws treated congregants equally—it removed the legal separation between men and women. From the reform perspective, there is no problem with women serving as witnesses. The qualification of being witness to a ketubah in the reform movement largely depends on whether one is a decent human being (of any sex) and a mature person (above b’nei mitzvah age). The orthodoxy, on the other hand, adhere to the following four requirements. In most cases, for a witness to be trusted, the witness must be

- Male

- A Sabbath observer

- Follows the laws of kashrut

- Fulfill the requirements of orthodox halakha (Hebrew: הָכָלֲה ; religious law)

Meeting these four requirements establishes the witness as someone is who trustworthy in the eyes of the community. At times, a witness may be trusted on this basis, even if they are not otherwise reliable. Moreover, it can serve as the basis for a get (גט ; divorce document) if a witness is found not to meet one of these requirements.

The Conservative movement has a variety of approaches. Depending on the community, some, more reform-leaning-conservative Rabbis, may follow the base rule that a ketubah must be signed by two witnesses. The witnesses, on this view, are signing a visual contractual agreement, and to be a witness to a contractual agreement does not entail belonging to a sexual category or following a denominationally-specific Jewish religious practice. Other, more orthodox-leaning-conservative Rabbis follow the orthodoxy requirements, entailing that the witnesses must be male. The official law is that women can serve as witnesses. In 1974, the Committee on Jewish Law Standards, acknowledging the change of the social status of women, voted that women can serve as witnesses, including on ketubbot (Grossman, p. 11).

The issue of who counts as a trustworthy witness brings out a difference between the community and the denominational fiat. There is an old Yiddish saying, “Every Rabbi makes the rules of Shabbos for himself.” Within a community, there may be variation among the congregants with regards to ritual practice; that is, who counts as a witness will, in part, depend on the members of the community to validate a trustworthy observer. As established by my own experience, there are Rabbis in the Conservative denomination who adhere to the same requirements for witnesses as the orthodox denominations: a trustworthy witness is someone who is male. Modern social norms, however, dictate that this requirement is prejudicial to women. Thus, the Rabbis in the conservative denominations must struggle with the dichotomy between changing social norms and adhering to tradition.

Rabbis of the Conservative denomination ought to consider that meeting the requirements of #2-4 (Sabbath observer; follows the laws of kashrut; fulfills the requirements of halakha) is quite different than meeting requirement #1 (male). For one thing, requirements #2-4 are choices a person makes in life. These are things one can either do or not do depending on one’s values. Following the laws of kashrut or keeping the sabbath are moral requirements. When one comes of b’nei mitzvah age, one makes the choice to meet these requirements. Consider, too, that requirements #2-4 are easier to misrepresent because it is not written for what period (years, months, days) one must fulfill the halakha before becoming a witness.

Since requirements #2-4 are not easily verified, it is left for conscience. Conscience in the Conservative movement is variable. Adherence to the requirements of halakha can vary between members. Some, like my father, drove to Shul every Saturday. He observed the sabbath in a modern way. After Shul, he napped, studied Torah with his children, and then watched baseball. That’s how he observed the Sabbath. He also kept kashrut both in the out of the home, but he ate at restaurants that weren’t kosher.

Other members of our Conservative congregation only kept kosher in the home but ate non-kosher meat in restaurants. Still, others only kept kosher when in Temple, but in their own homes or at restaurants they did not. Similarly, with the Sabbath, some members only went to Shul to pray on high holidays or during other special events (like for a b’nei mitzvah). Some just sent their children to Hebrew School and never came to services themselves. In the Conservative movement, there is more latitude for fulfilling the requirements of halakha. And this latitude makes adhering to the second, third, and fourth requirements of being a witness (that is being a Sabbath observer, following the laws of kashrut, and fulfilling other requirements of halakha) less certain and less verifiable.

The one requirement that is easily verified is being male. One’s biological anatomy is not a choice, unlike following the laws of halakha. Being male does not demonstrate one’s values. Choosing to fulfill the requirements of halakha does. If we are creating a more egalitarian society, the relevant consideration ought to be based on values, not on predestined biology.

Women As Witnesses

If the relevant consideration of who can and cannot be a witness is based on one’s values, as demonstrated through one’s choices, then biology is not germane. Women should be able to be witnesses if they are Sabbath observers, keep kosher, and fulfill other requirements of halakha— or meet whatever moral responsibilities a community dedicates to reliable observes.

The reason women have been excluded from participating in practices like witnessing is in virtue of a perception of biology and its relation to testimonial reliability. Women have menstrual cycles, and the menstrual cycle is associated with uncleanliness. Uncleanliness is associated with unreliability. Thus, women are not seen as reliable sources of testimony in virtue of their biology.

In an article published in the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly (2001), Rabbi Susan Grossman shows that Rabbis used to consider women’s testimony reliable only in cases when determining fact was necessary. For instance, a woman’s testimony about parentage was often considered reliable. This was quite important, as women carry on the Judaic bloodline. Children are Jewish if the mother is Jewish. A man without a Jewish mother—no matter how religious he is, whether he wears tefillin, doesn’t drive on Shabbat, keeps kosher, or is circumcised—is not himself Jewish.

In other regards, however, women’s testimony was considered unreliable, which disqualified women are witnesses (Grossman 2001, p. 3). This is a strange polarity: on the one hand, women are the bearers of religious progeny; on the other, they are excluded from, among other ceremonial practices, serving as a witness on the ketubah.

Rabbi Grossman argues that such a perception of women reflected the social status women held in society. Yet women’s social statuses have changed. Today, women have more equal rights under the law. Women serve as judges and lawyers, own businesses, and are physicians. The secular testimony of women is held in higher esteem in both Israel and the U.S.. In both the U.S. and in Israel, women serve on the Supreme Courts, as members of congress and parliament, and Governors. Indeed, Rabbi Grossman points out that the Rabbinic qualifications of being an eligible witness have not changed. What has changed is the number of those who now qualify (p. 11).

However, in the Conservative Movement, the legitimacy of women’s testimony is still under discussion. In response to Rabbi Grossman’s argument that women should be able to serve as witnesses, Conservative Rabbi Aaron Mackler argued that there are “great risks” to women serving as witnesses in some cases, such as divorce (2004, p. 2). He writes, “At the current time, the risks entailed by women witnessing gittin (divorce) are unacceptable. A woman’s witnessing a get would render that document ineffective for virtually all Orthodox rabbis, and some Conservative rabbis” (p. 4). He argues that the same can be said of marriage documents as well, although the “risks are small enough that, in many cases, a rabbi could in good conscious accept and even recommend such witnessing” (p. 4). Rabbi Mackler “hope(s) and expect(s) that the activity of women as witnesses will enjoy overwhelming acceptance among Conservative Jews…but that time has not yet arrived” (p. 4).

More recently, in The Theory and Practice of Universal Ethics – The Noahide Laws (2014), Rabbi Shimon Cowen argues that the Noahide Law (the universal message of Torah to humanity) makes women the determinant of familial relationships. This determination justifies the exclusion of women as testifiers on the basis that women have emotional reach, yet “justice calls for fixity in perception and a stilling of emotion” (p.261). He notes that excluding women as a sole witness applies only in the case of capital punishment. The reason is that taking the life of a criminal defendant (“the greatest ‘right’ of the human being) must be done with “dispassionate reference to the ‘abstract rights and universal norms’ set out by Divine—Noahide—law” (p. 263). Women “deliver, nurture, and protect life” (p. 262). As such, they cannot dispassionately judge cases of capital punishment.

This interpretation of Noahide Law as presently justifying the exclusion of women’s testimony, even in limited cases like that of capital punishment, circles a question I pose in my article: to what extent should modern concepts and/or arguments be taken into account? For instance, philosophers of science, since the ’70s, have challenged the assumption that ‘bad’ rational (or scientific) decision-making results if the practice is shaped by values, interests, and commitments (see, e.g., Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolution, 1970). Such arguments have been extended to medical decision-making, where knowledge (narrowly stipulated) requires a kind of transcending base experiences, which includes emotionality (see, e.g., Lorraine Code’ What Can She Know 1990). Code argues that requiring our concept of knowledge to be that which transcends experience creates a kind double-bind for women. Stereotypes that represent women as more emotional and less incapable of abstract thought indicate that women only have access to experience and are not capable of acquiring the relevant methodological tools required for knowledge (à la Aristotle). Indeed, exclusionary practices that keep women from authoritative positions as knowers are often rationalized on the grounds that men have access to both knowledge and experience and that women have inferior capabilities. Dichotomizing knowledge and experience in this way converge to keep women “within undervalued cognitive domains and thwart their efforts to gain recognition as authoritative members in epistemic communities” (p. 223). As Code, and others, have argued, knowledge does not transcend experience or emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence indicates the degree to which one understands how emotions affect one’s judgment. This kind of intelligence requires, not excluding emotion from rational judgments but rather, an understanding of what an emotion communicates about the situation and one’s interaction with it. It is a form of understanding one’s subjective location within the world and evaluating that location during the process of producing knowledge claims.

The debate within Conservative Judaism leaves my friends, Rebecca and Isaac, in a precarious position as they think about their future and the Jewish future of their children. They want to make sure that their children are recognized as Jewish. They want there to be no question about the validity of their marriage. What throws this into question is the fact that there are denominations of Judaism that would doubt a contract signed by a woman. This is a difference between what the law says and what is done in social practice.

It seems trivial not to allow women to sign ketubahs as witnesses. If women can’t be witnesses, what’s the value of a woman’s signature on the document? You can see where my grandmother signed her name in Figure 1. Her signature on the document indicates that she agrees to the contract. Rebecca will be signing her ketubah. It won’t be her father signing the contract on her behalf (as was once done). Rebecca’s signature validates the contract. But if Rebecca were to sign as a witness it would not be valid. A woman’s signature on the ketubah seems both valid and invalid.

When we come to a contradiction in our practices, it gives us good reason to reevaluate them.

Judaism is not inflexible. It is flexible in many ways. We are commanded to rest on the Sabbath, however, a doctor is permitted to work if a life is at risk. We are commanded to fast on Yom Kippur, however, it is acceptable to drink water or eat in conjunction medications. One witness is acceptable if it is impossible to find two to sign a contract. The priorities in Judaism have always been health (or life circumstances) then rules.

Indeed, the act of witnessing has undergone multiple changes. Epstein argues that, at one point, the witnesses weren’t required to sign the ketubah. Witnesses were only required to be named as present for the transaction. It was later reported in the mishna that a rabbinic enactment made signatures obligatory “for the convenience of the public” (Epstein 2004, p. 46-7). That is, at one point the law changed so that witnesses were required. With the rabbinic enactment, literacy became important for these transactions.

Another change to the act of witnessing occurred when it became impractical to witness deeds in person. The old way required both the witnesses and the contracting parties to be at the same place at the same time to validate the contract (Epstein, p. 49). As commerce expanded, this became less practical. The law was changed. The role of the witness diverged. One could be a witness as the ‘ede mesirah, that is to physically witness the transaction (p. 49), or one could be an ‘ede hatimah, a witness who signed the writ (p. 50).

Another change occurred when oral pronouncements of marriage were replaced by written contracts (p. 55). Originally, the marriage was pronounced by the bride’s father. In the Bible it is written, “Thus Laban says to Eliezer, ‘Behold, Rebecca is before thee, take her and go, and she be wife to thy master’s son” (Genesis 24, 51). Later the Talmud required the husband to make the pronouncement: “Behold, thou art consecrated unto me according to the law of Moses and Israel” (p. 56). Not only was there a change between oral and written pronouncements, but there was also a change with regards to who makes the pronouncement. The bride’s father was replaced by the husband.

Similarly, there were changes around the practice of the mohar (Hebrew מוהר , “the purchase price”). First, it was paid to the bride’s father, but later it was paid directly to the bride. At first, the mohar was a marriage price, later a divorce cost.

The best change of all occurred when women finally had to agree to the marriage contract, rather than just being like some beef sold. Eventually, she had to sign the contract herself.

Some areas of Jewish practice have no flexibility. The rules that exclude women from practice tend to be strict. This isn’t a Jewish or religious matter—it’s societal. Recall that it was through contact with Babylonia that the practice of a writ was introduced to the Jewish people. The Shetar, and the ketubah developed from it, was borrowed from a secular practice. That it was adopted from a secular practice reinforces the idea that the qualifications of being a witness ought to be flexible as secular practice changes.

If women are excluded as witnesses on ketubot, it reflects poorly on the relationship between words and deeds. Conservative Rabbis say they support the rights of women. However, the disparate actions of Conservative Rabbis, some refusing women as witnesses, demonstrates the opposite behavior. Disallowing women to serve as witnesses perpetuates injustice against women. The Conservative Jewish Movement should cement the requirements of being a witness on ketubot. Without cemented requirements, there is confusion, and women within the Conservative movement continue to be excluded.

Acknowledgment: My most heartfelt thanks to Rabbi Bernard Cohen for his guidance on the thoughts presented in this article. These ideas would not have been developed but for his kind direction. Many thanks also to my father, Mark H. Goldstein, for conversations and for finding the relevant literature sources, and also to my uncle, Neal Goldstein, for editing earlier drafts.

Share on Social Media:

References

21st Century King James Version. Copyright © 1994 by Deuel Enterprises, Inc. Complete Jewish Bible, Copyright © 1998 by David H. Stern.

Epstein, L. M. (2004). The Jewish Marriage Contract: A Study in the Status of the Woman in Jewish Law. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd.

Gittin 22B:1. Sefaria. (n.d.). Retrieved April 26, 2022

Grossman, R. S. (2001). Edut Nashim K’Edut Anashim: The Testimony of Women is as the Testimony of Men. Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly (HM 35:14.2001b).

Mackler, Aaron (2004). Edut Nashim K’Edut Anashim: The Testimony of Women is as the Testimony of Men: A Concurring Opinion. Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly (HM 35:14.2004d).

Orthodox Jewish Bible, Copyright © 2002, 2003, 2008, 2010, 2011 by Artists for Israel International.