It was a chance meeting in the valley that divides my Galilean Kibbutz Hannaton from the Bedouin village of Bir al Maksur, that planted the seed for the storyline of my debut novel, Hope Valley. I was out walking my dog when I saw Hussein, a shepherd who frequents the valley, out with his sheep; but this time, his wife was with him. She was foraging.

“Sabah el kher,” I said.

“Sabakh el nur,” she answered.

Despite my elementary Arabic and her non-existent Hebrew and English, we found a way to communicate, especially with the help of Hussein’s translation. When she asked me how old I was, and I told her, she started to cry. Her daughter, who had recently died from cancer, was my age.

When she told me more about her daughter, I said I wished I had met her. And that was the truth. I began to think how, if we had met, we might have connected over living with illness, despite the cultural differences and history of conflict between our two peoples. I live with a degenerative neuromuscular disease called fascio scapular humeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD). It is not necessarily fatal, but as the disease progresses, it can be, as at a later stage, it can spread to the respiratory system. I am already experiencing the effects of a weak diaphragm.

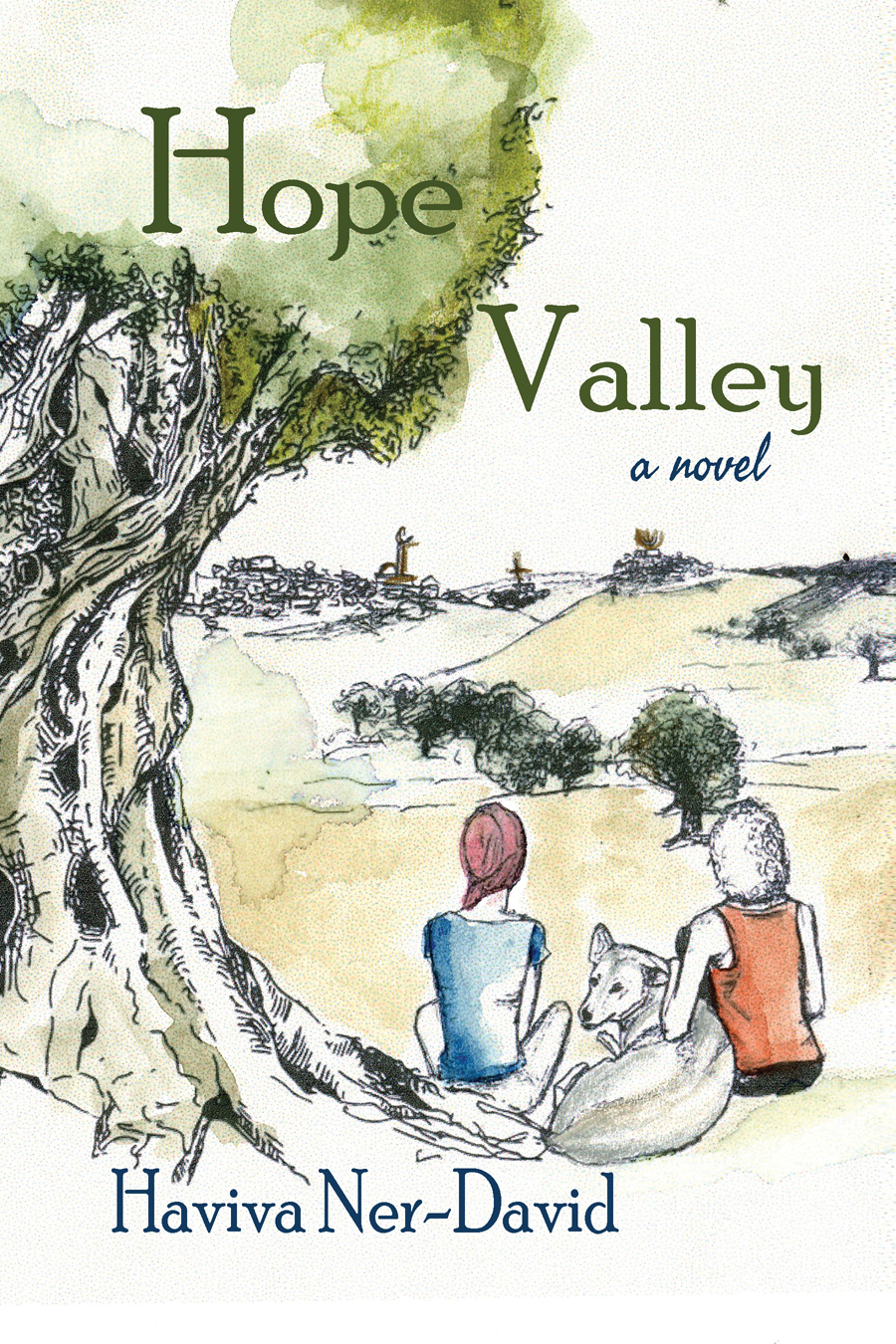

And thus, my novel, Hope Valley was conceived. It was born eight years later and tells the story of the unexpected friendship between a Jewish-Israeli woman U.S. ex-pat with multiple sclerosis, Tikvah, and a Palestinian-Israeli woman, Rabia (or Ruby), who returned from 25 years living abroad, to be treated for lung cancer. The two women meet one day during the summer of 2000, right before the outbreak of the 2nd intifada, in the Galilean valley that divides Tikvah’s moshav from Ruby’s village.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

While at first there is suspicion and resentment between the two women, who are both artists (although Tikvah is experiencing artist’s block and Ruby is well-known and successful), they slowly become friends. Tikvah is not me, but there are aspects of her with which I identify and wanted to explore in the novel.

For example, multiple sclerosis is not FSHD, but it is also a degenerative neuromuscular disease. And while I am not an artist, I am a writer, which is a kind of art.

There are other similarities as well. Tikvah, too, moved to Israel out of Zionist ideology, although hers was not from her upbringing, as mine was. Instead, she was attracted to her Zionist youth movement in search of a feeling of belonging — as her parents, Holocaust survivors but not Zionists, were distant as a result of the trauma they endured.

Like me, Tikvah, too, becomes more aware of the Palestinian narrative, although she does so through her friendship with Ruby. I, on the other hand, became aware of the Palestinian narrative through many friendships, not just one. And Tikvah, like me, has a daughter with a Palestinian-Israeli life partner (an important element of the story) who grew up in Jaffa — although her daughter and her partner are very different from my daughter and her partner. Tikvah’s daughter’s relationship plays an important role in her opening to the Palestinian narrative, while I was already on this path when my daughter and her partner met.

I will not give away the plot of the novel. In the first drafts, the story was told all from the point of view of Tikvah. After all, that is the story I felt most comfortable telling. But something was missing. I tried writing from the shifting points of view of Tikvah and her husband, Alon. But that, too, did not feel right. Writing from the point of view of Tikvah, the Jewish character, felt natural. She was not me, but she was close enough that I was comfortable stepping into her shoes and speaking in her voice.

I was in the process of figuring out the best way to tell this story, and all along, I think I knew, that the best way to make the story come alive would be to try stepping into Ruby’s shoes. But I did not know if I could manage it. It was a challenging task. Over the years, however, Ruby became a friend, a character I walked around with in my head and heart. At some point, I felt up to the challenge, and I gave it a try.

That is when the novel came into its own. I do not know if I did justice to portraying a Palestinian-Israeli woman, but I do think I did justice to portraying Ruby. And that is the point. She is an amalgamation of various Palestinian-Israeli women I know, as well as a unique character unto herself. I see many of my Palestinian-Israeli friends in her, and she is the result of the years I spent listening to their stories.

I am a member of a Palestinian-Jewish narrative-sharing group in my area. We get together once a month to hear life stories around the conflict. This may sound simple, but the idea is to not only listen, but to listen in non-judgment. To witness and be present, to hold space for the other, without letting your own story, thoughts, or national narrative, get in the way. It is an amazingly healing and opening process. Transformative, really. And this is part of what I was trying to get across in the book.

My younger children also attend a bi-lingual (Arabic and Hebrew) multicultural primary school. The school is not only for the children who study there, however. The organization that runs this network of Hand-in-Hand schools across the country, provides a rich community for the adults as well, with a wide variety of activities to help bridge these two sectors that are unfortunately highly segregated in Israeli society.

During the process of the book’s publication, the controversy over the novel American Dirt erupted. This is a novel about the Mexican migrant experience written by a woman, Jeanine Cummins, who is not herself Mexican. Reviewers accused the author and her publisher of cultural appropriation and “trauma porn”, of fetishizing the pain of another people. I worried Hope Valley might receive the same criticism, since I am a Jewish-Israeli woman who had the nerve to attempt writing from a Palestinian-Israeli woman’s point of view.

But attempting to step into the shoes of those with different experiences than ours is part of how we grow as humans. We are told in Pirkei Avot, Ethics of our Elders (2:4) not to judge another human until we stand in their place. Writing from another’s point of view is an extension of that concept. If we all practiced this exercise regularly, we would judge others less, which would create less animosity and conflict. The world would be on its way to healing and repair.

By attempting to step into my Palestinian-Israeli friends’ and son-in-law’s points of view, I am able to at least come closer to understanding the pain of having lost their family villages and/or homes in the 1948 Nakba (which means catastrophe in Arabic), and of living as a discriminated (and in some cases, threatened) minority in Israel — even if I can never feel it completely. As I could never be them. Just as they can never be me and know what it feels like to be born Jewish two decades after the Shoah (the Israeli term for the Holocaust that also means catastrophe, in Hebrew), and to live in Israel knowing I am resented (and sometimes even threatened) by my Palestinian neighbors.

Even if I myself have evolved ideologically and politically since I moved to this place and no longer support the idea of a Law of Return for Jews only in this country, I am still seen as a Jewish oppressor. Especially since I, an immigrant from the U.S., took advantage of the Law of Return in order to obtain automatic Israeli citizenship. I have Palestinian friends whose families cannot return to live here, or who themselves are here without citizenship in spite of (or perhaps even because of) the fact that their families lived on this land before 1948.

Hope Valley is not a one-sided novel. It is told from both points of view, because that is the message I am hoping to impart with the novel: that there are two parallel narratives that can sit side-by-side, and can merge to create a shared peaceful narrative moving forward. But this will require leaving our comfort zones and not only listening to each other’s narratives of trauma, but also processing our own collective trauma and integrating it, so that we can move past it together.

There are various levels upon which to read Hope Valley. It is a novel written by a Jewish-Israeli ex-pat from the U.S. coming to terms with her own responsibility as someone living as a Jew in the empowered majority in Israel, writing about (and from the partial point of view of) a Jewish-Israeli ex-pat from the U.S. who is doing the same.

It is also a novel written by a Jewish-Israeli woman attempting to feel into what it might be like to live in Israel as a Palestinian-Israeli, written partially from the point of view of a Palestinian-Israeli woman slowly befriending and growing to trust a Jewish-Israeli woman, despite her own resentments and family history.

That is the structure of the book. It would not have been possible to tell this story effectively without my attempting to speak from Ruby’s viewpoint. I know, because I tried. Plus, I did have Palestinian-Israeli friends read the book to check for plausibility of character and situation. But not to see if they identified with Ruby or would have said or done what she did, as they are not Ruby. Only Ruby is Ruby, and while she is a composite of various people I know and stories I’ve heard from their mouths and from research I’ve done, ultimately, she is the character I created for my novel.

It is possible what I am saying is not politically correct. But as a human being, a rabbi and interfaith minister, a spiritual companion and educator, I am not concerned with labels. I am concerned with the nuances of living in this complicated, challenging and sometimes beautiful-in-spite-of-it-all life. And as a writer – not only of fiction, but also memoir and personal essay — I am concerned with doing my best to portray life in all of its complexity.

Moreover, as the author of Hope Valley, I am concerned with drawing the reader into the reality of living in our times in this tiny strip of land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. This the reality I live and am steeped in and want to write about – it is not a reality from which I am far removed — but to do so only from only a Jewish character’s point of view would be perpetuating the problem. My hope is that I did the subject justice.

Following are two excerpts from the novel, both dialogues between Tikvah and Ruby. The first is from the scene when Ruby and Tikvah first meet, which is told from Ruby’s point of view. The context is that Tikvah is out walking her dog, Cane (who is part Canaan and acts as a bridge between the two women), and hears a gunshot. Cane takes off running, finds Ruby foraging in the valley, and leads her to Tikvah, who has a minor fainting spell and leans on Ruby, who walks her to a rock beneath an olive tree to rest. She leads Tikvah to believe, for a moment, that the gunshot was a terrorist attack.

Ruby sat next to the woman, took her knapsack off of her shoulder, and put

it on the rock beside her. She indicated for the woman to drink more from the

thermos. She was mildly sorry she had scared her. “Don’t worry. It was probably

some kids fooling around, or someone from my village out shooting porcupines

or wild boars.” She gave the woman a quizzical look. “What did you say your

name was?”

“I didn’t. You didn’t ask.”

“Well, what is it?”

“Tikvah. My name is Tikvah.”

“Which means what, again?” she asked even though she knew that word

as the name of Israel’s national anthem. In fact, she remembered some of her

Hebrew from when she had studied at the University of Haifa years ago. At

least the Jews had brought a co-ed university, and even secondary schools in the

villages, to Galilee.

“It means Hope.”

“Like the name of this valley.”

“This valley has a name?”

“Yes. Maybe not an official one, on your people’s maps, but all of the Arab

villagers around here know it. Hope Valley. Marjat Amal. And my village, there,

up on the hill across from your moshav, Bir al-Demue—that is on your maps,

so I assume you know what that means . . .” Tikvah shook her head. “Well, it

means Well of Tears. There’s a historic well in the village where women would

come to cry, their tears mixing with the water in the well. Hopes and tears.

Appropriate, considering the history of the area.”

Tikvah took another sip of water from her thermos and tried to stand. But

Ruby could see that she still felt too shaky to go anywhere.

“This tree we’re sitting inside, it has a name, too. Tree of Hope. Shajarat al-

Amal. This is the oldest olive tree in the valley. These trunks are all part of one

tree. My father used to take me here often when I was a kid. He said he named

the tree himself, before I was even born.” Ruby ran her fingers along the rough

bark of one of the tree’s trunks. “I used to say the tree had wrinkles. Legend has

it that this tree is around two thousand years old, and that it was planted by

Joseph when Jesus was born.”

“That would make sense. It’s a Jewish custom to plant a tree when a child’s

born. Joseph was Jewish. Jesus, too, as you must know.”

Ruby watched Tikvah examine the three gnarled and knotty tree trunks

and then look up, to where thick winding branches tangled together into a

canopy of thin oblong leaves, dense enough to shade the women from the

blazing sun.

“Well, this tree is amazing, whether or not Jesus’ father planted it . . .” Tikvah

looked at Ruby, somewhat apologetically. “I’m afraid I didn’t know any of this.

Not about the tree’s history, and not even its name.” Her tone was tentative.

“But speaking of names, what’s yours?” she asked, her voice becoming more

cheery, her body more animated.

“Rabia.”

“What does that mean?” Tikvah screwed the top of her thermos back on and

returned it to her knapsack.

Ruby decided she could at least educate this woman about the language of

the people who had lived here before she and the rest of those moshavnikim

came. Hebrew may have been an older language than Arabic, but it was used

only as a written language in Galilee for centuries until the Zionists came and

revived it as a spoken language. “It has the connotation of companion for life,

because Rabia ibn Keb was the prophet Muhammad’s companion. But it’s literal

meaning is spring.”

“As in the season?”

“Precisely. But people outside the village call me Ruby. It’s my professional

name. Just Ruby. No family-name. I’m an artist. The only Ruby Palestinian-Israeli

woman artist around. I’m pretty well-known internationally—although

less so here—even if I never had huge commercial success. Good enough to get

by, though. So I’m not complaining.”

Tikvah looked at her with interest. “Well, do you know what the name of

my moshav means? Sapir?”

“No, not really,” Ruby said, although she knew all too well what it meant.

“Well, it means sapphire. Not exactly ruby, but pretty close.”

Should Ruby tell this woman what the name of her father’s village had been?

What it felt like to be reminded of all her family had lost each time she heard

the name of this woman’s moshav? It was as if the Jews were waving an eternal

victory flag in the villagers’ faces.

“Are you feeling better now?” she asked, purposely changing the subject.

“A little.” Tikvah breathed deeply and closed her eyes for a few moments.

“Probably just a little dehydrated.”

Possible, considering the heat. Still, this woman looked generally unsteady.

Weak and shaky. Like it was more than just dehydration that ailed her. But

Ruby did not want to pry. She knew what it was like to want to talk about other

things, to think about other things. The thought that this woman might also

be unwell made her less antagonistic, less anxious to end the conversation as

quickly as she had wanted to just moments before. Even if the woman lived on

that moshav.

“Here, try this,” she said, releasing the buckle of her knapsack. She reached

inside and took out her burlap foraging sack, which she opened. She removed

from the sack one of the ugly brown roots she had collected earlier that morning.

“This is turmeric. You may know it as a spice in curry, but it’s also medicinal.

It’s an anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant, among other things. Do you want

to try some?” She took a pocket knife out of her bag and scraped some of the

outer layer off of the root. She loved watching the bright orange flesh of the root

slowly appear, like a sun rising up from behind the arid mountains.

Tikvah hesitated.

“Go on. I won’t poison you.”

Tikvah stretched out her arm. Ruby scraped some of the peelings into the

palm of her hand, and the woman put some in her mouth. “Yuck!” she said,

spitting the partially chewed root back out into her cupped hands.

Ruby laughed and took a bite. “Yes, raw it is pungent,” she said as she

chewed. “But you get used to the taste. My mother has me eating it constantly.

She makes tea out of it, too. With an herbal Bedouin remedy from the south.

Sheicha, or fragrant star. She says it’s a cure.”

“For what?”

She swallowed what was in her mouth. “Cancer, of course. Did you think

this was hijab I’m wearing here?” She lifted her hand to her head scarf and

pushed it back ever so slightly, to show there was no hair underneath. “I have

not covered myself since I left this place years ago. If a man has a problem with

me showing my hair, it is his problem, not mine.” She shifted her weight from

her right leg to her left. “Was his problem, I mean.”

“I’m sorry. It must be hard.”

It was hard. Even if this woman was living on the moshav, she did seem

sympathetic. Ruby did not have anyone she could talk to about her illness.

She did not want to worry her family. If this woman, too, was ill, she might

understand. No need to tell her the depressing details of her prognosis, though.

She just met the woman. “I was living in Manhattan when I was diagnosed. I

came back for treatments. This country is not a choice place to live if you’re an

Arab, in case you haven’t noticed. There are worse, but there are better, too. And

my village is not a choice place to live if you’re a woman artist with a mind of

her own. But I don’t have too many options at the moment. My healthcare is

covered here. I’m a citizen.”

“Well, that is important. Healthcare coverage.” Tikvah looked like she was

speaking from personal experience, but, again, Ruby did not want to pry.

“You lived in Manhattan? I grew up in New York. On Long Island. So I guess we’re

both transplants in one way or another. But I’ve been in this country longer than

I lived in the U.S. I have dual citizenship.”

Again, Ruby held herself back from attacking this woman, who could just

step off of a plane and get Israeli citizenship because she is Jewish, while Ruby’s

father’s family who were born here but had fled to Lebanon after their village

was destroyed in 1948, could not even return, let alone become Israeli citizens.

“Well, lucky for you,” she mumbled under her breath, but she said no more.

“And I’m lucky my family was living in Galilee and not the occupied territories,

or in Al-Quds—”

“—Al-What? Where?” Tikvah asked.

“Al-Quds. That’s the name for Jerusalem in Arabic. All of your cities have

Arabic names, too, in case you didn’t know. Nazareth, or Natzrat in Hebrew, is

an-Nasira in Arabic. Jaffa, Yafo, is Yaffa in Arabic. And Haifa is Hayfa.”

“Ok. So you’re glad your family’s not from Jerusalem? Why?”

“I mean East Jerusalem, where I doubt you’ve ever been. Like most Jewish

Israelis. Things are heating up there, and in the occupied territories, too, as we

speak . . .”

Tikvah looked at Ruby with curiosity and fear. Ruby decided to drop the

subject of the Palestinian cause. She could have reminded Tikvah of how

the Arabs did not have it so great here in Galilee either, what with the land

confiscations and the Judaization of the area, but she decided to give the poor

woman a break. She took another burlap bag out of her knapsack.

“Here. Try this,” she said, as she handed a leaf to Tikvah. “Saltbush. Returns

minerals to the system. It’s the desert version of spinach. Grows all year round,

even in this heat.” She wondered if she shouldn’t continue, but she couldn’t help

herself. When it came to her father’s village and the moshav, she let her emotions

get the better of her. “It’s native to Palestine, but they call it the desert colonizer.

It occupies places disturbed by human or natural processes. I’ll bet your moshav

is full of it.”

“Excuse me?”

“Well, if you call the Nakba a human disturbance.”

“Nakba?”

Ruby stood and stared at Tikvah. “Yes, Nakba,” she confirmed, with her free

hand on her hip bone, which she felt protruding from behind the fabric of her

jeans. “It means catastrophe. What you call the War of Independence, we call

the Catastrophe. Some people’s disasters provide benefits for other people, as the

old Arabic saying goes. My father’s village was destroyed, so your people could

build your moshav in its place.” She looked at Tikvah sharply, detecting surprise

in her face. “You didn’t know?”

Tikvah shook her head, slowly.

How could this woman not know? The privilege of winning the war. The

victors get to decide which story to tell and erase any trace of a different version.

“Well, they were expelled when you Jews captured the village in ’48, and were

never let back in. You really didn’t know this?”

Tikvah looked away. “I didn’t realize it was like that, exactly.” She looked

frazzled. “The story sounded different the way I heard it. You know, my parents

were refugees, too.”

“Refugees?”

“From Europe. World War II. What we call the Shoah. The Catastrophe. Our

catastrophe.”

Ruby’s face was getting hotter by the minute. “Well, being the victims of

victims doesn’t make it any easier for my people, if that is what you’re implying.”

And now an excerpt from Tikvah’s point of view. This scene takes place the next day, when Tikvah’a daughter, Talya, calls her while she is out walking Cane and tells her mother she is in a romantic relationship with a Palestinian-Israeli man. While they are talking, Tikvah does not realize that Cane has pulled her to the hole in the fence they had gone through the day before when they met Ruby. Ruby told Tikvah then that she and Alon are living in the house Ruby’s father’s family lost when their village was destroyed (except for that one house) in 1948:

Tikvah looked around to see where Cane had gone now that she was free.

There she was, standing in front of that same hole in the fence Tikvah had

walked through the day before. Apparently, no one from the moshav had gotten

to mending it yet. Cane was looking up at Tikvah. Come on, she was telling her

with mischief in her eyes. Tikvah stood and walked over to the dog.

“You want to go through again? Ruby liked you, didn’t she?” she said,

fingering Cane’s tail. “She appreciated you right away. And she did invite us back

to learn to forage. I’ve wanted to learn that for a long time. Wild mushrooms,

especially.”

One side of Tikvah wanted to run from the woman and never see her again.

What did Ruby want her to do, anyway? Even on the far-fetched chance the

house had once belonged to her father’s family at some point, was it Tikvah’s

fault someone had sold her and Alon the house?

Cane looked up at Tikvah and then at the hole in the fence.

But the other side of Tikvah was intrigued by the woman, felt drawn to her,

even, despite her belligerent exterior. She sensed her interior was softer than she

let on. She had never thought of an Arab as a tzabar, but why not? She too was

born and raised on this land. Perhaps she too had the qualities of a prickly pear.

And she was sick, too. Perhaps she was someone in whom Tikvah could confide

about her illness. Perhaps she would understand.

Cane gave one last look at Tikvah and climbed through the hole, her long

gray body fitting exactly between the wires, like thread through the eye of a

needle. Immediately, the dog headed straight towards the valley and began

frolicking in the meadow, running in circles and jumping at something—

perhaps a butterfly—in the air.

Tikvah put one leg through the hole. She pushed the loose fencing from her

face and lifted her other leg through, closing her eyes to protect them from the

sharp wire, even with her sunglasses partially shielding them. Once on the other

side of the fence, she surveyed her surroundings. The hills on the opposite side

of the valley, where the village of Bir al-Demue stood, were brown and barren

from the summer’s dry heat. They too were waiting for rain. Tikvah’s skin was

dry and chapped; she put cream on many times a day, only to need it more.

Her whole body craved the first rain of the season, which even had a name of

its own—the yoreh. She wondered if there was a name for it in Arabic, too—a

question that would not have occurred to her before yesterday.

Where was Cane? That dog was so hard to pin down. Tikvah had to keep

reminding herself that was not her goal. Only Cane could know what was

best for her. Yet, Tikvah was finding it increasingly challenging to give the dog

her freedom the more attached she became. She did not want to lose her new

companion. Ruby’s given name had something to do with being a companion,

she had said. Rabia. Companion for life. A beautiful name, really.

“Cane! Where are you?”

Tikvah started towards the olive groves, calling for the dog as she stumbled

further down into the valley, trying not to fall. And then there she was, up

ahead, coming towards Tikvah with Ruby by her side.

“Sabah el kher!” Ruby called out.

Tikvah did not understand. “What does that mean?” she asked, when Ruby

was just a few steps away.

“It means a blessed morning. Now you are supposed to answer, Sabah el

nur.”

“Okay. Sabah el nur,” Tikvah said. “What does that mean?”

“A morning of light.”

“Like in the Hebrew. When you tell someone boker tov, good morning, they

answer, boker or, a morning of light.”

“There are many similarities between the two languages,” Ruby said, as she

fed Cane pieces of something from her bag. Cane was jumping excitedly to grab

them with her mouth. “I almost gave up on you. It was beginning to seem like

you were standing me up.”

“I didn’t realize we had a date.” Tikvah had left their chance meeting with a

feeling that she would never see this woman again. At least not out of her own

volition. Had she been fooling herself? After all, here she was on the other side

of the fence, talking to her again, only a day after they had met.

Ruby abruptly took an empty burlap bag out of her knapsack and handed it

to Tikvah. “Follow me,” she said, and marched ahead, with Cane at her heels.

Tikvah followed too.

“What are we looking for?” Tikvah asked when she caught up with them.

“Saltbush,” Ruby said, stopping. She leaned over and started picking greens

and putting them into her bag.

“You mean that salty spinach-like leaf you showed me yesterday?”

“Yes. It’s all over the place this time of year.” Ruby handed her a leaf. “My

father lived off of the stuff when he was camped out here in the summer months.

And mallow in winter. After the war.”

Tikvah looked at the leaf in her hand. It reminded her of an arrowhead. “The

War of Independence? Or whatever you called it . . . ? The Nakma?” Ruby was

obviously convinced of this story her father had told her.

“Nakba, not Nakma. But you were listening to me, weren’t you? Yesterday.

Thank you.” Ruby looked at Tikvah and threw her a half-smile.

Tikvah and Ruby foraged in silence. Tikvah wondered what it was like for

Ruby to be back home after she had been away for so long. She wondered

what made her leave in the first place. But she was not sure she should ask such

personal questions.

“Have you ever made a mistake?” Tikvah asked again. She was still curious.

Ruby flinched and looked at Tikvah questioningly.

“I mean, foraging. You never answered me yesterday when I asked.”

“No, not really. I grew up with it. Like I said, it’s instinct at this point.” Ruby

looked up from her foraging. Her face became more serious. She looked down.

“But I did have a pretty close call once,” she added, lowering her voice. “When I

was inexperienced. With a husband, I mean. Not a plant. Those I can count on.”

Tikvah peered at Ruby. “You were married?” She had trouble picturing this

woman with a husband. She seemed so free. Unattached. And not easy to get

along with, either.

“Traditional Arabs don’t date. They marry. So it’s hard to judge if the shoe

fits without trying it on first. And then it’s too late to return it. But I managed

to get away, at least. Once he started hitting me.”

Tikvah stopped foraging. “He beat you?” This was even harder for her to

wrap her head around than picturing this woman married.

“Sure. I wasn’t born like this,” Ruby said, pointing to the bump on her

crooked nose.

Tikvah listened, stunned, and impressed by Ruby’s frankness.

“I found a shelter and bought a ticket out of the country as soon as I could.

I feared for my life.”

“Yes, of course.”

“Not just him. His family, too. I was branded rebellious for leaving.”

“His family would have killed you?”

Ruby put her hands on her protruding hip bones. “Of course. What planet

do you live on? Sitting on that hilltop—”

“—Listen, I’m not the enemy. That was your own people who pushed you

away.”

“True . . .” Ruby looked sorry for her outburst. “Chip on my shoulder.

Remember?” She leaned to one side, mocking being weighed down by a heavy

burden.

Tikvah felt sorry for Ruby, whose expression was saying she could use a

friend, despite her tough demeanor. “Aren’t you scared they’ll harm you now?”

“He’s gone. Went to live with family in Jordan and study engineering. He

married his cousin and stayed there. Started a family.” There was bitterness in

Ruby’s tone. “Apparently, he’s doing well for himself. And his father, his brothers,

well, it was a long time ago, and they wouldn’t dare kill a dying woman.”

“Was that meant to be a joke?”

“Am I laughing?”

“That’s absurd.”

“So is life, if you haven’t noticed.”

Tikvah had noticed. She thought of her telephone conversation with her

daughter less than an hour before. Of her own illness. Of Alon’s trauma. Of her

parents’ lost families and childhoods.

“I wish it all could have been different, but at least I got out of that marriage.

Because of that I was forced to leave the village. I saw the world, pursued my art.

If I had stayed here, I would have been dead. Even if not physically, emotionally

for sure.” She wiped the traces of tears from her cheeks with the backs of her

hands. “I never did marry again, though. Lots of relationships, but I enjoy my

freedom too much to settle down.” Tikvah sensed some reservation in Ruby’s

voice. “I learned from my mistake.”

Perhaps this new acquaintance could help her shed some light on Talya’s

relationship. There was no one else in her life she could talk to about this news.

“Well, my daughter just informed me now, on the phone, that she is seeing an

Arab man, from a Muslim family. In Jaffa. Apparently it is quite serious already.

What do you think of that?”

Ruby looked stunned. “From Yaffa? Interesting. But I told you Arabs don’t

date. Especially not Muslims. They respect Arab women too much.”

“Like your husband respected you?”

“I see your point. But they respect non-Arab women even less. Or they

respect them even more, but too much to marry them. Trust me on this one. I

know of what I speak. They see them as practice. Sexually, I mean. Or too much

as equals to marry them. When it comes to marriage, they want their own. They

want someone who accepts their cultural norms. I think I was too much of an

equal for Mustafa. That threatened him.”

Tikvah shuddered. “Well, I have to say, hearing your story makes me even

more nervous than I was already. And now this is making it worse. Talya, my

daughter, she says her boyfriend isn’t religious. His family is. He left religion.

Besides, I’m sure there are exceptions. You’re generalizing.”

“Sure, there can be exceptions. I assumed my ex was one, too. But often the

best swimmer is the one who stays on the shore, as my mother likes to say. And

there’s his family too. I told you what happened with my was-band”—Ruby

made quotation marks with her fingers—“and his family.”

This was not what Tikvah wanted to hear. “I’m also afraid of how my husband

might react if he finds out.”

“Is he violent?”

“Oh, no, nothing like that,” Tikvah said, shaking her head. “He’s just . . .

protective.”

“A hothead, then.” Ruby had her hands on her hips again, her fists clenched,

as if ready to return a punch if it came.

“No.” Alon was one of the most principled and disciplined men Tikvah

knew. Gentle, even. He had never come close to abusing her. Alon was like a big

mother grizzly bear; he’d protect his own with his life. She was sure of it.

“I said he isn’t like that. But I don’t think he could be rational about it. He

fought in Lebanon . . .”

“A soldier, eh?”

“He was an officer. He worked with dogs, training them for military use.

He’s retired now. He left the army after Lebanon. That war changed him.” Alon

had come home from Lebanon without Roi, but in the dog’s place in Alon’s

heart, there was a terrified creature who prevented him from letting anyone else

in.

“There’s no excuse for domestic violence. Not in the home and not in the

homeland.”

“Ah, ummm . . . Of course not,” Tikvah stammered. She had not been

expecting Ruby to react this way. “You know, I think you’d like Alon if you got

to know him. What you told me about your father reminds me of him, actually.

He too camped near the ruins of his childhood home. It was destroyed by the

Israeli government about two decades after you said your father’s village was,

although for different reasons. His mother, a dog trainer and breeder, had been

squatting. For twenty years.”

Tikvah thought she saw a glint of empathy in Ruby’s eyes, and for a moment

she believed that she and Ruby could become friends, that maybe she could even

bring Ruby home to meet Alon, and that had Ruby’s father still been alive, he

and Alon would have had a lot in common. If only history had not intervened.

Perhaps she and Ruby could make up for that.

“And his father? Where was he in 1948?”

“He too was a dog trainer. But Alon doesn’t remember him.” Tikvah lowered

her voice. “He worked with military dogs in 1948. In the Haganah. He died in

the war, apparently.”

The empathy Tikvah thought she had detected in Ruby’s eyes disappeared as

they clouded over with a look of resentment. “How can you compare kicking

out a squatter to razing an entire village? Don’t fool yourself. The only way your

husband and my father could have become friends would have been if he had

come to him years ago to apologize for what his father, for what the Haganah,

did. You know, that’s what my father said hurt him most—that no one from the

government, after the war was won and the State was firmly established, came

to say they were sorry.”

Tikvah felt personally attacked by Ruby, like she had before by Talya. What

were either of them expecting her to do now? Ruby refused to acknowledge even

one drop of pain her parents, Alon’s parents, or even she and Alon may have

suffered. Ruby may have been an artist, and she may have been sick, but she did

not understand Tikvah at all. She did not understand Alon at all. And she did

not understand their life at all. She wasn’t even making her feel any better about

Talya’s new romance.

“Alon would never hit me. Never. That’s your story, not mine,” Tikvah said.

“And now, I think I better go.”

Tikvah called Cane and walked off towards her side of the valley. She was

sorry she had confided in this woman. She should have trusted her original

instincts. Perhaps she would even sign that petition on her way home. But then

she remembered Talya and thought better of it.

Hope Valley’s ebook and paperback edition is available now on Amazon, as well as on Barnes & Noble, Apple Books and Kobo.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.