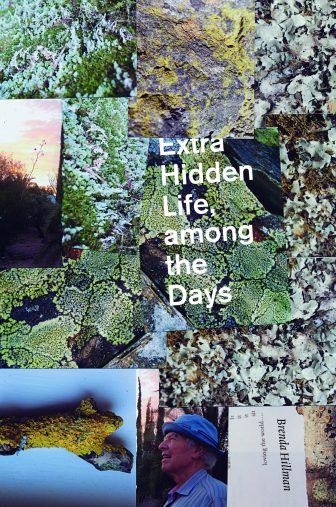

Extra Hidden Life, among the Days

Wesleyan University Press, Feb 2019

Cover image courtesy of Wesleyan University Press.

Brenda Hillman’s newest collection, Extra Hidden Life, among the Days, is the first since her elemental tetralogy (Cascadia, 2001; Pieces of Air in the Epic, 2005; Practical Water, 2009; and Seasonal Works With Letters on Fire, 2013), an ambitious project which used the four elements to explore the role of poetry in the face of climate change. The tetralogy’s scope – and each book’s achievement both as an individual collection and as part of an epic, decades in the making – is uniquely bracing in contemporary poetry. “When they ask ‘What are you working on now that the elements are finished,’” writes Hillman, anticipating the kind of question that follows in the wake of a big project, “i say the elements are never finished; in China they have metal, in India they have ether, in the West we are short on time” (“Whose Woods These Are We Think”). In the same way that the elements conceptually organized each previous book, the “element of time” is essential to Extra Hidden Life, an ecopoetical elegy for Hillman’s loved ones, for nature, and for political activism. The concerns vital to her tetralogy – the relationship between body and environment, the efficacy of activism, the role we play in climate change – remain present in her new collection, but the speaker views them through a lens of grief, speaking as one who has been granted “extra life,” or an “element of time,” past each object of mourning.

Such multi-valent mourning is not just a theme in Hillman’s new book, it’s baked into her language itself. In his review of Seasonal Works With Letters on Fire, which appeared in the spring 2015 issue of Tikkun, Michael Morse describes the importance of prepositions in Hillman’s work, noting that prepositions serve as a “tethering tool … that locate [the poem’s] emergence in time and place and in juxtaposition with other phenomena.” In Extra Hidden Life, among the Days, Hillman turns prepositions towards the work of negotiating grief. She frames her newest collection with an epigraph from Judith Butler on what it means to bear grief, and what to do when grief feels unbearable: “is there another way to live with it that is not the same as bearing it?” Hillman’s collection responds with particular pressure on the phrase “with it.” Her poetry treats grief as an object that can be traded or swapped; she questions what the mourner can “put in its place,” and what it means to have been given “extra life,” life that extends past those she mourns. And there are many things to mourn: the grief of losing those close to her, the sense of futility that often accompanies political activism, and the grief that accompanies climate change and the devaluation of ecological experience. Hillman suggests that poetry is a means by which we can “bear” grief – be with it, among it, and make room in our everyday lives for it; grief itself can be a form of activism. Grief is generative; mourning is response, and so a form of responsibility.

Throughout Extra Hidden Life, Hillman engages with one of the core dualities of activism: its vitality and its futility. In “Hearing La Boheme after the March” – which occurs on an airplane after the 2017 Women’s March in Washington D.C. – the speaker says that “broken songs are not for rallies They’re to keep nearby/ while you prepare to act without results,” but adds that “The day was pretty magical / That’s not a lie / There’s energy / in some complaining.” In “Crypto-animist Introvert Activism,” Hillman tackles the way activism often feels like it doesn’t make a difference – and grief that accompanies this sentiment: “Every week for about a decade some of us at school have been standing at lunch hour to protest … It’s an absurd situation & it changes nothing”; however, for the speaker, “the protest is absurd but i admire these forms of absurdity.” Activism is a means to live past grief and employ her “extra life”: “When the revolution comes … some will rise & some will dance & some will lay our bodies down.” Here, the action of grieving becomes a form of protest. Grief carries with it a sense of powerlessness, but Hillman’s transformation of grief into protest – a protest both of what’s lost, and the fact that the speaker remains behind – enables her to reposition and reclaim grief.

Nature and global warming are as crucial to Hillman’s newest collection as they were to

her elemental tetralogy. The book ends with two odes to nature – one to a national forest, the other to a national seashore – which interrogate nature’s ability to provide an avenue through grief. These are poems of replenishment, in which “after such sorrow / we dreamed a red ladder of / birth & death being set down,” where the sun “greet[s] the soul / of the day,” and “humans walked to the edge of the sand / through a bank of verbena and fog; / they thought they’d never get over / the deaths, but they were starting to.” Although nature is solace, it causes her to grieve as well; it is both problem and solution. Nature provides no true way “past this impossible sorrow” implicit to her collection, and Hillman pushes back against allusions to the English Romantics, especially their tendency to personify nature, as the lichen “warn each other in teal / or celadon & humans assign / meaning to this, saying they are distressed / or full of longing.” Nature may provide a way to “bear” grief, to live alongside it; but it does not provide a way to transform grief, or a way out of mourning.

Hillman’s investment in naming, and poetry’s capacity to fix nature in time, is another example of the speaker’s attempt to contain and make use of grief. In the book’s third section, she catalogs the taxonomy of lichen, which then becomes a linguistic network that ties together personal, cultural, and environmental grief: “Xanthoria break- /ing things down, ‘fairly common on bark …’/ if you peel a piece of it from history the rest continues – ”. Her impetus to name nature before it’s destroyed feels urgent; Hillman calls poetry “the ambulance of art”; nature “will last for a while in your poem / But you can’t write the names of species / Fast enough before they disappear.” This feeling of powerlessness echoes the experience of living in a political climate in which nature is systematically devalued, and where a constant in our lives – the environment – is rapidly, and irrevocably, changing. While “a metaphor,” to the speaker, may be “a form of action,” the poet knows, too, that the medium of writing has little capability to keep nature from harm:

the humans tarry, looking down at high waves crashing,

green with its leader into gray, crashing over what is lost;

the humans name what is lost while going home where

they live in violence & hope & inconceivable longing –

Elsewhere, Hillman sees the “cadence” of butterflies “become … our anxiety,” and notes that “some like to avoid the word nature / but what to put in its place?” She addresses the grief of losing an entire environment, a climate, a place of permanent residence. One of the most painful elements of grief is the sense of accompanying powerlessness – the feeling that there is nothing to “put in the place” of what you’ve lost. Another aspect of this powerlessness is the uncomfortable feeling of being left behind; the speaker asks

what had been in us before?

a life that asks for mostly

wanting freedom to get things done

in order to feel less

helpless about the end

of things alone–;

This sentiment carries guilt; it is uncomfortable; it is one of the clearest examples of why grief feels unbearable.

What can poetry do in the face of such grief? Poetry, in Hillman’s collection, is a way to sit inside the discomfort of grief, to make something of this discomfort. As she argues in her elegy for C. D. Wright:

When people ask why we need poetry

they know

they know what it is

We don’t read recipes at the grave

We don’t read tracts & theories at the graves

Poetry doesn’t provide a solution, a formula; it provides a through rather than an out, and gives us “power for changing / not-life into lives.” In “Whose Woods These Are We Think” – the same poem in which Hillman says that the “element of time” is a means to move past the work she accomplished in her tetralogy – she offers a direction for Extra Hidden Life:

What do people need from poetry during the changes? The changes are immeasurable … many people need calm poetry … & i would certainly write that way if i believed calm were key to any of it, but if what woods are left are lovely, dark, deep, they are also oblique, obscure, magical, owned for profit, full of fragile unnamed species, scarce on time, time that barely exists though people base their lives on imagining it does. i hoped to find some wisdom to send back to you & that is what i am working on now, my present hopeful wild & unknown friends …

It may not be fashionable to say, but Hillman’s collection is full of wisdom: these poems are “oblique” and “wild” and full of energy. They bring us into the poet’s grief, and give us a way to move through and out. They remind us what we stand to lose – personally, culturally, even existentially – but they give us a way to both bear and claim these losses.