C.T.Vivian and John Lewis, two extraordinary men who committed their lives to the work of justice have died. They have joined the ancestors. They have moved from time to eternity after having lived lives of Maat.

Maat is an ancient Egyptian system of thought that understands that each individual is part of a cosmic order, We are connected to each other, all of nature and creation. It is part of our moral responsibility to live a way of life that establishes and maintains truth, justice and righteousness. In the ethics of Maat, when human beings live lives of truth, justice, and righteousness, they bring their own characters and lives in harmony with the cosmos. Truth begets truth. Justice begets more justice. Righteousness begets more righteousness. When we act with courage, we become more courageous. Maat was part of a system of philosophy and religion that was already ancient before biblical times. It exists in many systems of philosophy and religion especially when individuals realize their oneness with all of Being.

C.T.Vivian and John Lewis lived lives of Maat, not episodically, but their entire lives were examples of a total commitment to justice and peace, using the methodology of nonviolent resistance. In 1947, C.T.Vivian, the elder of the two, participated in his first sit-in in Peoria, Illinois to integrate Barton’s Cafeteria. In 1960, when he was a student at American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee, he and Lewis, also a student there, joined with Diane Nash and other students from Fisk and Tennessee State Universities to desegregate lunch counters in Nashville. It was during this time that both Vivian and Lewis learned the philosophy and techniques of nonviolent resistance taught by James Lawson. Lewis was on the front line with Nash, Angela Butler, and others marching to the stores. The wider Black community supported the sit-ins with a boycott of downtown businesses. Vivian stood with Nash as she confronted Nashville’s mayor, asking him directly, human being to human being, if he thought segregation was moral. Mayor Ben West answered “no”. Three weeks later, the lunch counters were desegregated.

In 1960, when the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) decided to challenge segregation on interstate buses, John Lewis felt something inside, urging him on to volunteer to be a Freedom Rider. In a letter to CORE stating his desire to join the Freedom Riders, John Lewis says that human dignity was more important than his formal education. He wanted to help justice and freedom come to the deep South. Within the context of Maat, as courage begets courage,the courage Lewis needed to face the violence perpetrated against the students sitting-in at lunch counters become strong when he and other freedom riders faced the violence of vicious mobs who were willing to kill to preserve segregation and white supremacy.

Courage is the ability to move forward, to do what ought to be done, in the face of fear. However, fear was not the emotion Lewis says he felt when the trip started. He says: “I felt good. I felt happy. I felt liberated. I was like a soldier in a nonviolent army. I was ready.”

In an oral history connected with the documentary “Eyes on the Prize” and Washington University, C.T.Vivian explains that the movement started with desegregation of lunch counters and buses because these were the spaces of daily injustice and humiliations. On city buses, Black people had to pay the fare at the front of the bus then board the bus from the back door. If the bus was full, they would have to give up their seats to a White person. In interstate bus travel, Black people had to go to the back of the bus when they reached the apartheid south. When Black people went shopping, it was an injustice, a humiliation, to be refused the right to sit at a lunch counter and eat when the store was perfectly willing to take their money in retail exchange. Maat is truth, justice, and righteousness in cosmic unity and harmony. Segregation is based upon the lie of white supremacy. It is unjust and unrighteousness because it denies the humanity and the holiness of people based on the color of their skin. It turns White people into monsters willing to kill to preserve untruth.

When the freedom rides almost came to an end because of violence in Alabama, students from Nashville came to keep them going from Alabama into Mississippi. Lewis stayed, even after having been beaten. C.T.Vivian and others joined. Vivian described the reaction of Black people as the Freedom Riders passed by: “We’d take off across country. We can see people on porches and Black people on porches. Going through the Black part of town, they’re just waving, you know, and we’re waving back. It was really tremendous, old folks sitting on the porch as they normally do, and it was really a wonderful thing. Their hopes were on us, you know, and we were supposed in fact to do what we were doing and to make it so that one day their children would not have to put up with what they had to put up with.”

Vivian, Lewis, and others were working for the human dignity of both present and future generations. In Mississippi, the Freedom Riders did not face mob violence, but they did face institutional violence, being sent directly to Parchman prison once they exited the buses and went into the white section of the bus terminal. More students came, black and white, from across the nation. Parchman prison became a pedagogical space where people of various races and religions taught each other. Lewis describes it: “The people who took a seat on these buses, that went to jail in Jackson, that went to Parcchman, they were never the same. We had moments there to learn, to teach each other the way of nonviolence, the way of love, the way of peace. The Freedom Riders created an unbelievable sense of yes, we’ll make it, yes we will survive and that nothing but nothing was going to stop this movement.” In Maat, truth begets truth. The Freedom Riders were successful because in September of 1961 the Interstate Commerce Commission passed a regulation that ended segregation on buses. It has been described as an unambiguous victory.

In 1963, a long-term vision of A. Philip Randolph became a reality when the various civil rights organizations come together to plan and to execute a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom with Bayard Rustin as its principle organizer. As chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lewis had a speaking role. However, his speech was militant. He spoke with the impatience of youth and invoked General Sherman’s march to the sea during the Civil War to speak of the destruction of white supremacy in the South. Such imagery was unacceptable to the Kennedy administration, keeping an eye on southern votes for the 1964 election. The other leaders implored Lewis to edit his text. He did. Still, it is important to listen to the entire speech.

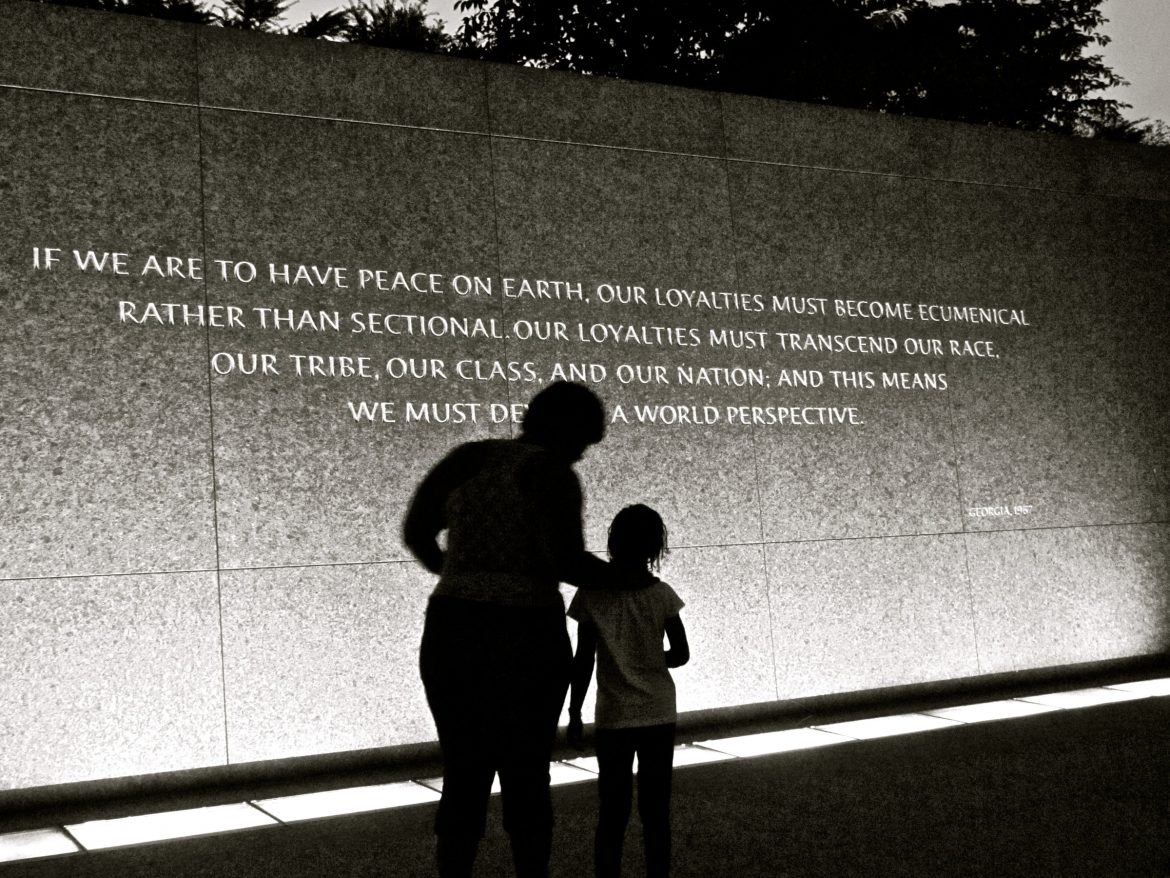

Lewis spoke of people who still lived in circumstances from which he came. He spoke of people working for starvation wages and of sharecroppers; he spoke of students who could not be at the march because they were sitting in jail; he spoke of the need for federal law to protect peaceful demonstrators; he spoke of voting rights. He criticized both political parties, stating a need for a party of principles. He demanded freedom now: “How long can we be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now? We do not want to go to jail. But we will go to jail if this is the price we must pay for love, brotherhood, and true peace.” Lewis called on the entire nation to join “this great revolution that is sweeping this nation.” Rather than invoking Sherman, He finally said: “If we do not get meaningful legislation out of this Congress, the time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington . . . . But we will march with the spirit of love and with the sprit of dignity that we have shown here today. By the force of our demands, our determination, and our numbers, we shall splinter the segregated south into a thousand pieces and put them together in the image of God and democracy We must say: Wake up America! Wake up!” For we cannot stop and we will not and cannot be patient.”

A few weeks later, September 15, four little girls were killed when the forces of stubborn hateful white supremacy bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The 16th Street Baptist Church had been the location from which King and SCLC launched the Birmingham Confrontation in the Spring of 1963. This is where King had been jailed, from which he penned the classic “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” It was the Birmingham confrontation that stunned the nation and the world with images of demonstrators attacked with dogs and firehoses. It was also the confrontation that allowed children to participate in justice and freedom work. That Sunday, four little girls — Addie Mae Collins, Carol Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson — were killed by a bombing. In a Spike Lee documentary “4 Little Girls”, James Bevel and Diane Nash both say that the movement was faced with two options: 1) to locate and kill the people responsible for the bombing 2) work for voting rights. Diane Nash says:”That if Blacks in Alabama got the right to vote, they could protect their children.” According to Bevel, the Selma right to vote movement was born.

For more than a year, SNCC worked in Selma organizing Black people to vote when Selma’s Black leaders called on King and the SCLC. Then, the two groups worked together on voting rights. Confrontations happened with Sheriff Jim Clark on the courthouse steps. C.T.Vivian confronted both Clark and his deputies: “This is not a local problem gentlemen. This is a national problem in the United States. You can’t keep anyone from voting without hurting the rights of other citizens. Democracy is built on this. This is why every man has a right to vote regardless.” There is a sense of oneness and connection in Maat. Vivian told Clark and his deputies that he was willing to be beaten for democracy.

According to Vivian, the confrontation for voting rights was deeper than the vote. It was a confrontation with human dignity at stake: “With Jim Clark, it was a clear engagement between the forces of movement and the forces of the structures that would destroy movement. It was a clear engagement between those who wished the fullness of their personalities to be met and those that would destroy us physically and psychologically. You do not walk away from that. This is what movement meant. Movement that finally we were encountering on a mass scale the evil that was destroying us on a mass scale. You do not walk away from that. You continue to answer it.” This is an insistence upon justice. This is Maat.

On February 18, Jimmie Lee Jackson was beaten and shot during a demonstration for voting rights in Marion, Alabama. Eight days later, he died. In response to this death, as a nonviolent technique to channel the anger of the justice workers into the work, SCLC decided to march from Selma to Montgomery. SNCC did not agree with this strategy, but John Lewis, still chairman, decided to participate. He not only joined the march, but he led it. He stood with Hosea Williams at the front of the line to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in what would come to be known as “Bloody Sunday.” John Lewis was beaten to unconsciousness. Others were also brutally beaten. However, as was the case with the boycotts and the sit-ins and the freedom rides, the movement refused to allow violence to stop the movement.

Joined now by King, the SCLC put out a call for others to participate in a Selma to Montgomery march. Many people answered the call, including 450 white clergy. The march was scheduled to begin the Tuesday after Bloody Sunday, but a federal judge issued an injunction against the march. King led approximately 2,000 marchers to the bridge where they knelt and prayed when they confronted Alabama state police. After the prayer, King turned the march around because he did not want to violate a federal injunction. He asked those who had come from around the country to stay. James Reeb, a white Unitarian Universalist minister and activist was with two other clergy when they were attacked by segregationists. Two days later, Reeb died of his injuries. Reeb’s death caused nationwide outrage, and people took to the streets in protest. March 15, President Johnson spoke before Congress calling for a voting rights act. Then, the judge lifted the injunction and ruled that the march could proceed.

On Mach 21, the third attempt of a Selma to Montgomery march started. Now, the number of marchers had grown to 25 thousand. Old and young, black and white, people from a variety of religious traditions, people from across the nation, marched for five days. Again, John Lewis was on the front line. It was during this march that SNCC joined and started to organize a black political party, the Black Panther Party, in Lowndes County.

In August of 1965, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. After this, SNCC’s commitment to nonviolence started to wane. Stokely Carmichael with a nationalist ideology and a rhetoric of black power became chairman. Lewis moved to New York to work for an organization involved with issues of poverty. When Robert Kennedy decided to run for president in 1968, Lewis again raised his hand to go to the front lines. He wrote to Kennedy and volunteered for the campaign. He was with Kennedy in Indianapolis, Indiana when Martin Luther King, Jr, was killed. He campaigned with Cesar Chavez in California, and he was in the campaign suite in the Ambassador Hotel the night Robert Kennedy was killed. Charles Evers, Medgar Evers’ brother who also died recently, was also present that night. Lewis knew that he could not give up, so he ran to be a delegate to the Democratic convention in Chicago.

During this time, the gaze of the popular culture shifted from nonviolent civil rights to the radical chic of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. They presented a very different image in natural aftros, black leather jackets, black berets, and openly carrying long guns into the California state capitol. They also advanced a radical multiracial revolutionary program that influenced other grass roots organizations such as the American Indian Movement and Chicano liberation groups. J. Edgar Hoover saw these groups as dangerous to the status quo, so much so that he sought to destroy these organizations through a counterintelligence program known as COINTELPRO. The tactics of the FBI ranged from internal surveillance through informants to outright murder using local police as the murderers. This was the case with the deaths of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in Chicago. All the while, Vivian and Lewis never lost their commitment to truth, justice, righteousness, and cosmic harmony. They never lost their commitment to Maat.

There is a line in the song “Everything Must Change” that says: “The young become the old and mysteries do unfold cause that’s the way of time nothing and no one goes unchanged.” C.T. Vivian and John Lewis lived to be old men.They lived to not only tell the story of the civil rights and human rights movements, but they lived to inspire and share their experiences with younger generations. They lived to allow us to see what a lifetime of living breathing Maat looks like. President Barack Obama remembered meeting John Lewis when he was a student at Harvard Law school. He met him again when he was a United States senator, and as president, he awarded both Lewis and Vivian the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Lewis never stopped reaching out to young people through popular culture writing a serious of graphic novels. The last public photo of Lewis was him standing on Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, DC.

In an essay published in the New York Times on the day of his funeral, an essay written when he knew his death was near, Lewis wrote: “You must also study and learn the lessons of history because humanity has been involved in the soul-wrenching, existential struggle for a very long time. People on every continent have stood in your shoes, through decades and centuries before you. The truth does not change, and that is why the answers worked out long ago can help you find solutions to the challenges of our time. Continue to build union between movements stretching across the globe because we must put away our willingness to profit from the exploitations of others.”

This is Maat. It is truth as eternal as the cosmos that tells us that the work of justice, righteousness, harmony and balance is the reason for our living on this earth. And when our time on this earth is over, we will have done our part to help the moral evolution of humanity so that all may live lives of sustenance and joy, so we all may live lives of Maat.