What do the Hallmark Channel, the Present Occupant of the White House, and some of my left-wing friends have in common? Hint: it’s not a thorough understanding of human rights.

Yesterday was Human Rights Day, celebrating the 71st anniversary of the adoption of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This noble document, written by survivors of World War II, marks a milestone in human history, the emergence of human rights as universal, not to be transgressed in the name of any cause or regime.

There is always a gap between any declaration—aspiration—and lived reality, to be sure. But my topic today is how fully and fulsomely the gap has been stuffed with indifference and hate by politicians, by commercial culture, by the embodiments of unquestioned entitlement. And my examples run that gamut.

First, a tribute. Eleanor Roosevelt is often mentioned as a key figure in drafting the Declaration, and deserves honor for her role. But my favorite character in the Declaration’s story is Rene Cassin, a hero and sage of human rights. You can read more about him and link to the Jewish human rights organization bearing his name in an essay I wrote honoring him in 2007.

I am in no way an essentialist. I see no evidence that any religion, skin color, gender, orientation, or condition renders any group of human beings superior to the rest. I am repelled by the corrupt habit of mind that ranks us by complexion, historical suffering, association, as if oppression were a contest. When I say that human rights are indivisible, I mean both the world and our minds can hold knowledge of and empathy for many experiences simultaneously. Compassion can stretch to infinity. There is no need to conserve or withhold it for fear of running out.

I am sad at how many experiences I’ve had—how many others I’ve heard about—that treat the way Jews are made use of by bigots and the entitled as something negligible. How often it is seen as not worthy of the attention, compassion, action that flow toward other invidious prejudices. And I am angry at the way some Jews collaborate with this bigotry.

I’ll start with them.

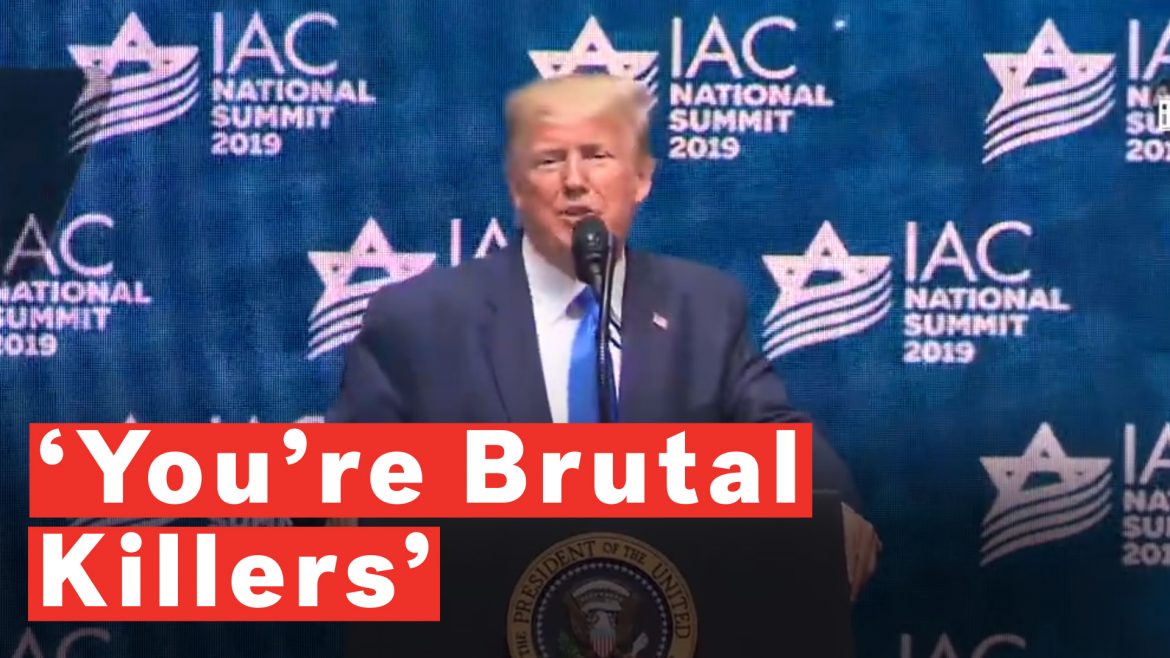

The Present Occupant of the White House made a speech last week to a conservative Jewish group that was a long string of bigoted insults packaged as confiding insider jokes, for example:

“A lot of you are in the real estate business, because I know you very well. You’re brutal killers, not nice people at all,” he said. “But you have to vote for me — you have no choice. You’re not gonna vote for Pocahontas, I can tell you that. You’re not gonna vote for the wealth tax.”

He got laughs. And cheers. You can read a detailed account of his speech here. And an account of the objections it raised here.

The wealthy and right-leaning Jews gathered for the speech in no way represent American Jews as a class. As the second Washington Post article cites, a Gallup poll puts Trump’s approval rating among Jews at 29 percent (as opposed to 31 percent of Latinos); and as a Paul Krugman column on the same topic cites, only 17 percent of Jews voted Republican in the last election. What the Jews who showed up for Trump in Florida represent is the sizeable proportion of Republicans, regardless of ethnicity or religion, who vote for their personal profit over all other considerations. They should be ashamed.

(Responding to an avalanche of criticism for his speech, the president will today sign an executive order declaring Judaism a nationality. Ostensibly undertaken to protect free speech on campus, the order separates Jews from other Americans. Think back to other times and places in which Jews were assigned a status apart from other citizens. What could possibly go wrong?)

But what about this moment in U.S. history? Now is the time in which a president of the United States feels utterly free to make such statements, just as he felt free to say some of the Nazis who marched on Charlottesville were “very fine people.”

Trump is the excrescence, of course, the malignant growth thrusting out of the darkness. So is the vandalization of the 6th and I Synagogue in Washington, DC, last week. So are the murders in Pittsburgh, Poway, Kansas City, and elsewhere in the last few years. So is the sharp upturn in incidents of antisemitic violence: “ADL’s most recent Audit of Anti-Semitic incidents in the United States recorded 1,879 acts in 2018, with a dramatic increase in physical assaults, including the deadliest attack on Jews in U.S. history.” And I’m only talking about things that happened in the U.S.

But what is the humus, the soil from which these virulent growths spring?

It’s a culture that has turned its back on the indivisibility of human rights, instead parsing prejudices and oppressions, making excuses, choosing not to notice.

I always feel it at this time of year, when the ubiquity of Christmas and all the cultural exclusion it symbolizes start to impinge on my goodwill. A friend recently asked me why this season gets me down, and I sent her a couple of links to earlier essays answering that question. Read “Christmas in America,” which I described when it was published in 2005 as “a cathartic essay.” Then I invite you to read “My Xmas Kvetch” from 2012 for a exploration of cultural hegemony, symbolized by the far-right’s campaign again a so-called “war on Christmas.”

Long ago and far away? Read Britni de la Cretaz’ opinion piece in the Washington Post about her optimism on hearing there were two new Hallmark Hanukkah movies being released, and her pained disappointment at realizing…

There’s just one problem: Neither movie is a Hanukkah movie. They are Christmas movies with Jewish characters. And they rely on some of the oldest anti-Semitic tropes in the book.

The thing that made me saddest lately was encountering a fellow progressive, a fellow Jew, who insists that there is no meaningful antisemitism in the U.S. (and yes, he has not been living on Mars; he knows about the Nazis marching to “Jews will not replace us” and the dead bodies at the Tree of Life Synagogue). His argument? That “Jews have become white; and that so many Jews are in powerful positions–politics, money, media, the arts,” and that this somehow cancels the seriousness of impact of antisemitic acts, even the most violent ones.

This is an absurd argument, in that there are powerful people in every racial, ethnic, and religious category this society uses to cull its members—a black president (though so far never a Jewish one), Jay-Z and Beyonce as billionaires, the median income for Asian Americans 40 percent higher than for all Americans…and so on. The fact that some members of a group hold political and economic power in no way cancels acts of hatred and violence against them. How could it? I could never imagine the man who laughed off antisemitism telling an African American friend to laugh off a police murder or church fire because after all, we had a black president and a ton of black celebrities are rich. Or a Muslim friend to laugh off that mosque fire because Hasan Minaj has his own show on Netflix, Ilhan Omar is in Congress, and Sahid Khan owns an NFL team.

As for the “Jews have become white” part of the argument, it contains a truth and a falsehood. The truth is that whiteness as a privileged status has been granted to various immigrant groups in this country, including pale-skinned Jews. But a second truth is omitted: this status is always provisional. It can be revoked at any time, and that fact is indeed relevant, as I explored in this 2017 essay. In it you’ll see links to several important analyses, including Eric Ward’s brilliant “Skin in The Game.”

The falsehood is that by no stretch of the imagination are all Jews white. Did you read about Tiffany Haddish’s “Black Mitzvah?” Have you heard of Be’chol Lashon? The Jewish Multiracial Network? The Jews of Color Field Building Initiative?

I could go on listing, but here’s the point: when even progressive Jews who espouse values of justice and equity find a way to dismiss hatred of and violence against Jews, something is very wrong with our understanding of human rights. I’ll say it again: human rights are indivisible. If you make an exception for any group—if you paint a picture of the world in which attacks against certain groups are more forgivable, amusing, and benign than against others—the consequences will crash down on all heads. The death of universal human rights is an equal-opportunity plague. Let’s not let it loose.

Here’s the song I offered with “My Xmas Kvetch” seven years ago: “Far Away Christmas Blues” featuring Esther Phillips, Mel Walker, and Johnny Otis. Worth another listen.