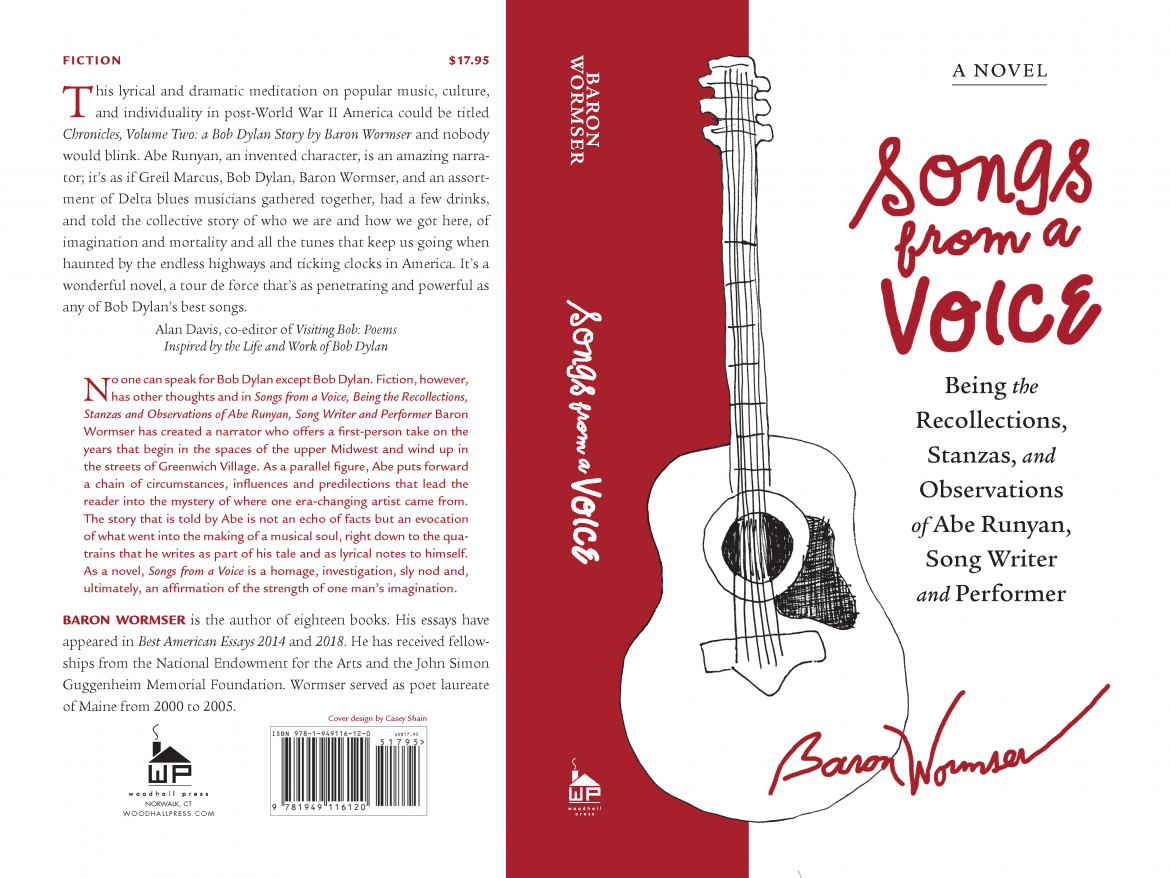

Songs from a Voice

Being the Recollections, Stanzas, and Observations of Abe Runyan, Song Writer and Performer

By Baron Wormser

CT: Woodhall Press, 176 pp. $17.95 (paper)

Where does Jewish music come from?

This novel is about music, imagination and Jewish roots. And about belonging and not belonging, freedom that comes from being an outsider, creativity and fame. It is also a thought-monologue of inner ideas and reality, and musings that the author sustains with no slackening of interest. It’s not easy to write a book like that. This novel’s protagonist, Abe Runyan, an invented character, is a fusion of Bob Dylan and the author, in a sort of symbiosis.

Bob Dylan (born Robert Allan Zimmerman) for more than half a century has been defying musical conventions. His songs from the 60s, especially “Blowing in the Wind” and “The Times They Are A-Changin,” expressed what everyone felt in his bones but could not yet articulate. He went from being influenced by older folk songs to ripping apart folk music with electrified rock instruments, all still within the 60s and before he went back to folk music. His range continues to be astonishing. A true Jewish legend, his versatility continues to the present, always creating new forms in different genres and receiving awards, including the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Abe of this novel continues the breaking of rules to create new forms, new ways to express the deepest part of the self, the Jewish soul and the quest for originality. The author has created a new form of novel, a new genre of inner awareness from a fictional character modeled on the fusion of a real person with the author, plus poetry. Straining for freedom, not to live every moment being told what to do and consequently not to feel alive describes part of the monologue. It is also a process of discovery, of finding himself as an artist, of extricating himself from what he calls “small talk” and finding the “large talk.”

Songs from a Voice opens with a classical temptation scene. The first voice we hear in this tantalizing novel is the snake’s, a rhyming poet itself, informing a young Abe that he will be a successful musician and song writer. Abe has been walking home in his usual dreamy way, filled with doubt, not knowing his destiny and feeling overly proud the way school boys do, when this snake crosses his path. We know the snake from Eden well, the one that Eve answered and Adam cowered before. It offers a deal in a highly rhythmic voice. When Abe quickly answers no equally rhythmically, the snake astutely says: “I get that you’re big on yourself, which is nothing new with your kind—blind human mind, groping and hoping and, as they say, these self-pleased days, coping.” And finally, “My abode is the crossroad where the soul gets sold.” Their banter continues. At the end, we don’t know who won. This prologue reminds me of the Coen Brothers’ film “A Serious Man,” where a Book of Job-type narrative follows its mysterious first scene. But here sweet and easy success follows, the kind yearned for by others in the coffee houses where Abe played the guitar and sang the novel’s unique songs written by Wormser. The action goes from these boyhood Midwestern streets to Greenwich Village to world-wide fame that Abe slips into almost nonchalantly.

The structure is divisions, not chapters, led by quatrains (here a stanza of four stand-alone lines of poetry, two of them rhyming). The quatrain that begins the work, with an end rhyme in lines two and four, is:

“The vanquished nights were dark and cold—

Words froze in brittle air—

I looked for light in the silent sky—

My heart so unaware.” p. 5.

The quatrains that fill the spectacular novel can match Dylan’s own easily, and Wormser’s lyrics travel higher into the world of poetry. Abe talks to himself and readers as he spills out his deep and brilliant mind generously.

Where does Jewish music come from?

This novel is an ode to imagination. In real life, both Bob Dylan and Abe are Jewish, neither from a cultural center, and both create poetry that comes solely from their imaginations or the mystery of nowhere known. Dylan and Wormser both said the lyrics came to him from someplace else. “Even the songs I made weren’t of my making. They issued from something much larger than I was.” (p. 77) Abe talks and thinks about the poet’s visions as being more real than reality, greater than the surface of the real. (p. 131)

Dylan is Jewish on both sides, but he doesn’t go to synagogue or live as a conventional Jew. Wormser is a Jew on both sides who also is secular. Both, however, have deep Jewish roots and an inescapable Jewish soul. A primary inspiration of this novel is the feel of silent and noisy Jewish roots.

In the discourses on universal themes, Abe gives his deep and brilliant views on many disparate subjects. On metaphor and the earth, he writes: “Metaphor, one thing turning into another, both startles and reassures. Through its far-and-near reaching, you feel how everything is connected and how that’s not presumptuous bull but more like literal, more how we tend to be busy and aren’t listening, more like how what seems incongruous isn’t. If we were listening, we’d hear some—always a fraction, though—of what’s spoken by the trees and rivers and the creatures too, the famous birds and bees. When I learned that whales sing to each other, I wasn’t surprised.” (p. 37)

About love and loss: “Loss may be the deepest feeling…. Love runs around and makes noises, but loss sits there on the splintery bench and broods.”

“Her love became a taunting fire—

The fire turned cold and gray—

The dark became the morning sky—

Blessing another day.” (p. 40)

He writes about folk songs passed on from generation to generation having something holy about them, whereas in the US everything is about today and not yesterday. The old folk songs had true feeling and not this false happiness, a happiness for the whites, not the blacks, he mentions. Abe was from the heartland like Woody Guthrie, but he came later and was Jewish and hungered for poetry.

“I sang the son about new love—

I sang the one of grief—

I stood and watched you go your way—

My voice beyond belief.” (p. 44)

He revisits the 50s, his childhood, the nightmare of the ‘bomb’ that could destroy anything, anyone, the air raid drills, and fear of the Russians dropping their bomb.

“I felt the heat, a blast on my face—

My body began to fade—

Everything fell—

The sky fell too—

All the making unmade.” (p. 51)

Rock ‘n’ roll brings Abe to life, “…the sound was like the crackle of a fire turned into music” and “…stung like a tribe of bees.” (pp. 66-7)

He says: “My ancestors’ songs were in my head too—the wailing of repentance, the Jewish blues. Once when I was visiting one of my mom’s brothers, it was Yom Kippur; we went to the synagogue and I heard it for myself, that long thin line of perishable sound.” (p. 81)

The author puts the words in Abe’s mouth about the immensity of the immortal.

Abe too veers away from college, a profession, what he calls “a settled life” with professional degrees. Instead he has songs in his head. He has to find who he is, and home prevents him from doing just that, a familiar story. Old feeling from ancient times reverberates into cutting-age modern, revolutionary, but tied to the rhythms and sounds of Judaism, though the rhythm seems close to hip hop.

“The heaven-sent stories collapsed—

I’d have to write my fate—

The crucial actor fell asleep—

The watchman came too late.” (p. 103)

Aloneness and being cut-off are themes in today’s world. The long monologue, also expresses isolation. He writes about reading Frost whom he found a little too sure of himself but who represented a life of words. He writes, “He probably would have had his problems with me. That I was Jewish and from some small town in the Midwest would have been too freaky. How could someone like me be a poet? There was nothing poetic about a life of “Pass the meatloaf,” or “It’s going to rain tomorrow.” Life ground the words down to dust.” (p. 123) He writes about dropping out of school, making his parents unhappy. “Jews are people of the book, not the guitar.” (p. 124) His parents were upset that he was throwing away his orderly life for singing for spare change. That is an old story and hardly peculiar to Jewish parents.

Where does Jewish music come from?

The end pages of this innovative novel are about the Jewish condition. “Part of the stranger role is … a few thousand years of being on the outside and looking in. It seems natural that I’ve wanted to take on the characteristics and situations I’ve made up in my songs. I’m making up for lost time. I’m making up for what was denied to my forbears. And I’m staking my claim—me too, mine too. There’s a special reverberation to the emptiness for me. My people kept to themselves and were kept to themselves. I remember when I first came upon the word “ghetto” and looked it up. What was that about? How could we be that wicked? How did we live? Barely and deeply, I came to realize.

“…how the Jewish part of me never goes away. How could I lose something that ingrained? Every time I speak, I hear it in my intonation, that sort of bemused whine.” (pp 135-6)

In high school, a girl he had been going with for a couple of months breaks up with him because he’s Jewish. “”Abe,” she said, “we’re not going together anymore.” She paused to finger a necklace she was wearing, a thin chair of glass beads. “I’m afraid what they say about Jews is true.” She turned and walked out of the room.” (p. 137) “You wouldn’t say what Mary said if I were another Christian American.” “The invisible mark was on me, the one that went back forever, the one I had ignored because who cared about such an old story that took place in a desert?” He contemplates this old story that keeps taking place and finds a familiar solution. “You could focus on what people thought you were, or you could elude those thoughts by making up your own. I wasn’t going to hide, but I wasn’t going to believe what Mary or anyone told me about myself.” (p. 139)

A relative speaks nostalgically about the old country, Ukraine.

“Grandma Reva used to talk about the old country, back in Russia where there were peasants and mud, dark bread and the czar’s soldiers. She would go into a kind of singsong lament about the Jews and how hard they had it, how America was the end of their bondage. She wasn’t, by any stretch, what you could call a patriot. American ways were permanently peculiar to her…I never visited the old country, but I’ve imagined myself being at home there. That’s more about the slowness of life, conserving what might be precious, how hurry is never the way to go.” (p. 144)

Abe misses ballads: “What’s kept speaking to me in the old ballads is their unswerving feeling—the testimony of blind passions and hovering darkness. There’s a knife’s edge in those songs: lost love, abandonment, sudden death, revenge, stolen kisses, rivalries, the feeling that we’re held in the tangle of our memorable circumstances, some of our own making and some not. The ballads gave me a pleasure that was historical, the feeling of drama as both located and timeless, but also something else, the feeling that people lived a step or two away from every kind of duress—what once got called ‘Fate”—and that it would be a mistake to push that insight aside.” (p. 145)

“I got off a boat and looked around—

Fear looking back at me—

Found some rooms, a wife, a job—

Murdered my childhood country.” (p. 147)

Unlike most in the coffee house, Abe is noticed, gets a good review in the newspaper, slides to fame. It’s music, not the snake, that tests him.

If you love music, the coffee house milieu with folk music, or if you are interested in the search for belonging even with a history of not belonging; or the search for becoming who you are; Jewish roots and all its pleasures and sorrows; if you love poetry—then this novel is a home.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.