As the author of this “appreciation,” it is more than a little ironic that when I first encountered Herbert Levine’s poetry, I was in no mood to appreciate poetry of any kind, especially (given my wholly secular outlook) religious poetry.

I only started browsing through Levine’s Words for Blessing the World: Poems in English and Hebrew at the urging of my Rabbi sister who assured me that this was a work that would resonate with me as it did with her- despite our theological differences.

And she was right. Levine’s poems, far from the self-absorbed obscurity that characterizes so much of modern American poetry, actually did have something important to say to me. The poems jolted me awake with their clarity, insight, and fresh expression of a new Judaism that is both intellectually enlightened and spiritually uplifting: a new Judaism in which the possibility of a religious-secular humanism is fully realized.

A tall order indeed! But Levine, using the format of side-by-side English and Hebrew versions, had found a way to make the journey to Jewish spirituality accessible, pleasurable, and memorable.

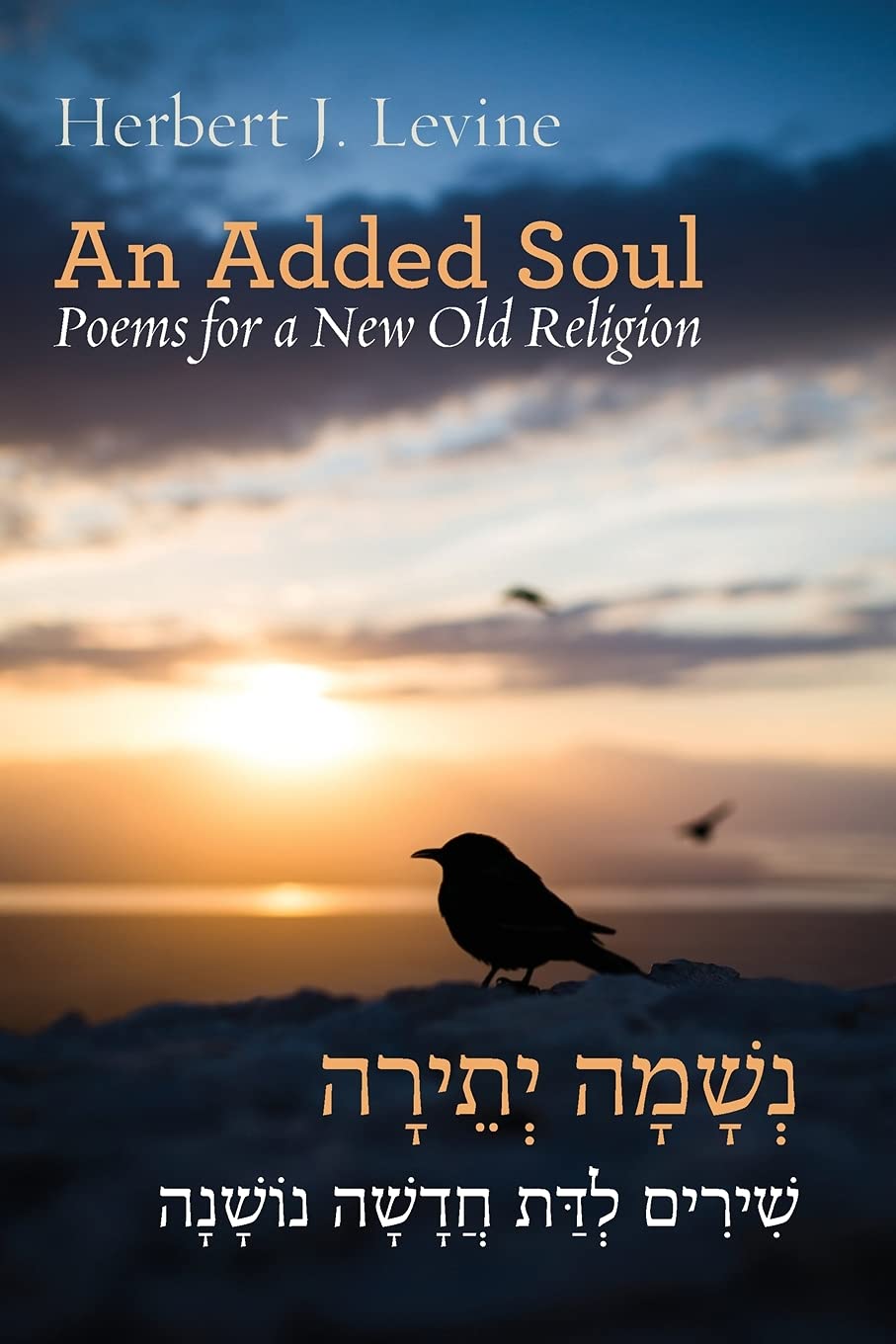

In his new work, An Added Soul: Poems for a New Old Religion, Levine continues on this journey, extending and amplifying the themes he developed in the first volume. For readers who may be new to Levine’s work, I’d like to offer a few words on why I think it’s a worthwhile journey to take, especially for those of us who seek to outgrow the limitations both of secular humanism and traditional Judaism.

Levine’s poetry is suffused throughout by a singular vision of an evolving Judaism that replicates his own spiritual growth. Deeply respectful of his ancient Hebrew roots, Levine sees a transition of Judaism away from God-worship, not as a departure from Jewish tradition, but as a continuation of the iconoclastic challenge taken up by our earliest patriarch:

Just as the lad Abram put a hammer

In the hand of the biggest idol

In his father’s workshop

and pointed to it as the one who shattered

all the rest, so our father Abraham

put that self-same hammer in our hands…

But the fulfillment of young Abraham’s mission, Levine makes it clear, is not simply the destruction of false gods, nor even their replacement by a single divine entity. It is, rather, the recognition that the proper object of worship is the world itself.

. . . . .so that we might destroy images of God

which, since then, have screened us from seeing

that there is nothing holier than the world.

“Don’t Think There Is No Prayer,” in Words for Blessing the World, p. 8.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

The recognition that one need not look further than the very world we live in to experience a profound sense of awe and gratitude is central to the “New Old Religion” that Levine envisions. This vision of a sanctified, holy, but very real world is essential not only to Levine’s conception of an evolving Judaism, but is also central to Levine’s own spiritual growth. The foundational stories of the great Western religions are seen for what they are: naive fantasies from our tribal ancestors that fail to address the needs of a modern global community:

The sea splits, the heavens open,

a man dead for three days walks the highway.

horse and rider fly through the air to the holy city,

the fat man comes down the chimney—

O civilized world,

drowning in a sea of unreality.

What we need, Levine writes, is “A New Kaddish” that sanctifies our immense, diverse but interconnected world:

Let’s create the next version:

make the world holy

without old stories, without masks.

paint with all the hues,

play with all the instruments of the orchestra,

speak with all the languages, write with each alphabet

names of all creatures who have ever lived;

from these, let us make a great name,

shmay rabba that includes them all,

serving us as both lament and prayer.

Yitgadal v’yitkadash—

Let us make that great name

great and holy.

“A New Kaddish,” in An Added Soul, p. 2

A more personal and painful step forward emerges in “I Make A Covenant Of Peace With You.”

I make a covenant of peace with you,

Reb Meshullam Zalman Schachter-Shalomi.

Thirty years I followed your lead;

I sought to bless and draw blessings from the universe

through the language of our ancient prayers.

I no longer can. To birth the future

like you I strike at the rock of the past.

Zalman, a colorful and charismatic leader of the Jewish Renewal movement, offered many young Jews, disaffected by the emptiness of the conventional religion of their parents, a wholly new appreciation of their ancient religion by encouraging them to experience the intense spirituality they were searching for through music, meditation and a creatively reinvented liturgy centered on a mystical union with, rather than mere obedience to the God of the Torah. Stepping away from Zalman’s inspiring influence must have been a tumultuous experience, but Levine’s powerful insight that the world itself- with all its faults- is reason enough to pray, compelled him to declare his independence from the veneration of all deities, however creatively re-defined:

….To birth the future

like you I strike at the rock of the past.

“I Make A Covenant Of Peace With You,” in Words for Blessing the World, p. 44.

But as much as Levin sought to go beyond the limitations of a God-centered spirituality, his acute awareness of the spiritual dimension of our world, awakened through his immersion in Zalman’s Jewish renewal, enabled him to see the limitations of the secular humanist alternative to traditional Judaism.

In “Blessed are you, World,” Levine acknowledges the chutzpah of a pioneer kibbutznik from the 1920s whose Passover Kiddush is dedicated not to the Biblical God who delivered us from Egypt, but to the community that Jews of his generation built with their own hands:

In the archives of Kibbutz Beit-HaShita,

I discovered forgotten hand-written notes

for a Passover Seder from 1927.

Instead of the Kiddush,

the author wrote, “Blessed are you,

kibbutz”….

But Levine knows that, when we come together at Passover to express thankfulness, the object of our gratitude must go beyond our human achievements, no matter how laudable, and should extend to this wondrous, magical world that we are blessed to inhabit.

….In his footsteps, I widen the blessing circle

and say, blessed are you, world —

to praise your fragile, complex beauty.

“Blessed are you, World,” in Words for Blessing the World, p. 2.

Here, Levine envisions a new Judaism that, while fully embracing secular political and ethical values, is not confined to the realm of secular humanism. To that end, he offers us not a polemic, a sermon, or a “parsha”, but rather a love song to our “blessed world.”

For Levine, the emergence of a “New Old Religion” of secular spirituality is not some distant goal. It already exists in the everyday experience of Jews throughout the world, especially among those for whom traditional Jewish practices have become an impediment rather than a stimulus to genuine spirituality and ethical sanity. Echoing the sentiments of the Living Theater, Levine understands that we need not await the coming of a Messiah to achieve “Paradise Now.” It is attainable now, in our own lifetime; not by obedience to a set of divine commandments, prophecies, or ritualistic formulas, but by the exercise of fundamental human values:

A new old religion

without gods and holy worship

and commandments engraved in stone,

without ecstatic dances,

without prophets and crazy riddles:

At its center,

how Ruth followed Naomi out of love,

how Boaz opened his hand and his heart to Naomi and Ruth,

how he gave them six overflowing measures of barley,

how he prevented his young men

from harassing the attractive stranger.

how he bought an unneeded field

to heal a broken Naomi.

The lion will not lie down with the lamb.

With kindness, the world to come can come now.

“A New Old Religion,” in An Added Soul, p. 30.

Of course for many modern Jews, Levine’s proposals for a new secular Judaism are already quite familiar. Levine’s most important contribution, therefore, is not so much the articulation or the envisionment of secular Jewish spirituality as it is the creation of a unique poetic medium for its expression. The music of poetry, beyond mere words on paper, goes directly to the heart. It is not only communicative of our spiritual yearnings but is, by its very nature, a pathway – a vehicle- for experiencing the spiritual dimension of our world; a lesson Levine undoubtedly learned from his “rebbe,” Walt Whitman:

From my grandfather I inherited tefillin

and an old volume of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

Mornings, I put on his tefillin and read in his book,

“Why should I wish to see God more than this day?…

In the faces of men and women I see God

and in my own face in the mirror.” Like him,

I know with every atom of my body

that all men and women are my holy brothers and sisters

and that my spirit is also tied to the plants in the field

and to the far stars.

Every time I read in his book, I come to know,

as did my unknown grandfather,

that I will follow this rebbe all the days of my life.

“What I Received as an Inheritance,” in Words for a Blessed World, p. 42.

Because poetry offers unique communicative possibilities beyond the reach of prose, (which, alas, tends merely to confirm what we already believe), Levine’s important insights become accessible to a wide diversity of seekers- from traditional believers in search of intellectual integrity and non-believers in search of authentic spirituality.

Then too, Levine’s use of side-by-side, English and Hebrew versions of his work offers much more than the opportunity to reach a wider audience. It deepens the appreciation not only for those able to compare the texts but also for people like me whose Hebrew education is limited to long-forgotten Bar Mitzvah lessons.

For me, the significance of the Hebrew text lies precisely in its mystery and archaic solemnity-

its direct linkage with the very words read and sounds uttered by countless generations of my ancestors. Standing alone without the facing Hebrew version, Levine’s poems would still have a powerful impact- but positioned alongside the Hebrew text, they become part of our collective history.

Imagining Levine’s poetry arising from the mouths of our ancestors helps fortify our hopeful conviction that the movement away from a God-dependent Judaism is not a departure from our heritage, but rather a legitimate, necessary evolutionary development.

It’s as if our ancestors have given their blessing to the emergence of a vital new branch of our menorah.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.