“The true art of the untrammeled cartoonist is now being developed and …will be one of the most inspiring factors in the propaganda of the revolution.” Eugene Debs’ introduction to “The Red Portfolio: Cartoons for Socialism” (1912)

Eugene Debs might have been writing the introduction to the recently published graphic biography devoted to his life. Eugene V. Debs: A Graphic Biography, has just come out, edited by Paul Buhle, with Steve Max and Dave Nance, and with art by Noah Van Sciver. Paul Buhle was editor of the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) journal Radical America. From 1967 through the 1970’s, Radical America was devoted to educating the New Left about the history of American radicalism, about theoretical currents in the international left, about independent Marxist thinkers like E.P. Thompson, C.L.R. James and Guy Debord, as well as about the humanism of Marx’s early 1844 Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts. It was my great honor to work with Paul as a co-editor of that magazine for a short time in the late 60’s. In a 2015 interview in Viewpoint Magazine about his work on Radical America, Buhle has said he asked himself such questions of radical history as, “What are the lessons that can be learned? And what hidden strengths…can be grasped by social history?” All these years later, these same questions are informing Buhle’s graphic novel projects*. Whether or not this book fully answers these questions or whether or not it falls into what Debs referred to as the “propaganda of the revolution” remains to be seen. This particular graphic biography, unlike others in the series, is significantly sponsored by Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), and is intended to help educate a new generation of young millennials, opened to the idea of socialism by the 2015 campaign of Bernie Sanders. It is also intended to show the history of DSA in the context of the era of Debsian socialism. I believe this joining of historiography and the DSA accounts for both the book’s strengths and its weaknesses.

A Graphic biography of Debs and Debsian socialism

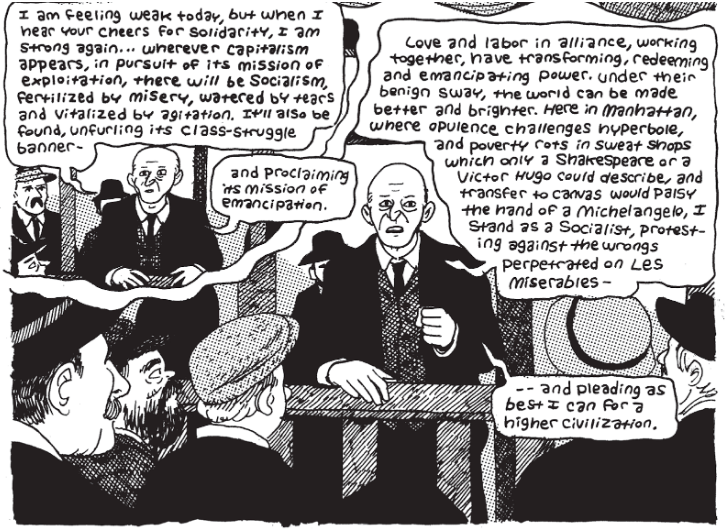

One of the strengths of this book is its timing. It is a welcome and inspiring illustration of the heyday of American socialism just when we anticipate a neo-McCarthyist style attack on “socialism” from the right—the harbinger of which was evident in Trump’s State of the Union address. The book provides an engaging and enjoyable broad history of early American socialism as the background for a look at the life of Eugene V. Debs, the only American socialist who got nearly a million votes in his campaign for the US presidency in 1912. The graphics are another of the book’s strengths–it is in the graphics, wonderful straightforward line drawings by Noah Van Sciver, in a style reminiscent of the great socialist cartoonist Art Young that the book comes to life. Beginning in almost a storybook fashion with an idyllic view of Terra Haute, Indiana (one is reminded of the opening scenes of American farm life in Garth William’s illustrations for Charlotte’s Web), the book shows Deb’s family origins. He was born in 1855, just eight years after Karl Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto, after the February Revolution ended the French monarchy and wave of revolutions swept through Europe. His parents were French immigrants who, with social conscience, named their son after the novelists Eugene Sue and Victor Hugo.

Text and graphics take us through the evolution of Debs’ life and politics– from his early utopianism to labor unionism and his commitment to organizing both skilled and unskilled workers in the American Railway Union, through the Pullman strike and its drawing together of many unions and many races, and finally, to socialism. We see in procession some of the important names in socialist history, with wonderful characterizations of Robert Ingersoll, Daniel De Leon, Big Bill Haywood, with whom Debs started the IWW (the Wobblies), Samuel Gompers, with whom Debs argued against the “labor aristocracy,” and Victor Berger, whose anti-immigrant racism Debs challenged. We see, too, Debs’ association with artists and writers, like Jack London and Mark Twain, and his appreciation of the importance of a cultural dimension to radical politics.

What is Debsian Socialism?

Image courtesy of Verso Books.

This graphic biography cannot be, nor does it attempt to be, a complete history of socialism, or of Debs. For that complete and more complex history, readers should turn to the classic Debs biography by Ray Ginger, The Bending Cross, or the more recent biography by Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs:Citizen and Socialist. The power of graphics and cartoons is their ability to, as Art Spiegelman puts it, “essentialize” topics. In the process of “essentializing”, however, graphics run the risk of simplification, unable to really grapple with complex issues, such as the nature of Debsian socialism, about which many books and articles have been written, and many heated debates have ensued. This book’s picture of Debsian socialism emphasizes some it its aspects–Debs’ ability to attract multitudes to the idea of, and to vote for, socialism, and for his strong stance on the solidarity necessary between skilled and unskilled labor, for his fight against racism in unions and in the Socialist Party. Other aspects are not emphasized. What thrilled me when I, as a young college student, learned about Eugene Debs, was not his voter appeal, but his humanism and his notion of leadership. His humanism was manifest in his faith in and commitment to the self-activity of the workers to achieve a socialism which would elevate all of humanity. “Love and labor in alliance, working together, have transforming power. Under their benign sway, the world can be made better and brighter.” Debsian socialism was about the process of creating a future in which men and women, of all races and ethnic backgrounds, would be free to realize fully their humanity. It was his profound and confident belief in the ability of people to create socialism as they struggled to achieve it that empowered and attracted so many people to his Socialist Party.

Debsian socialism was not about great or charismatic leaders providing socialist or even reformist, policies for the people or even about winning elections–it was about people themselves creating their own future. As Debs so articulately put it in his Canton, Ohio speech (1918), “I am suspicious of leaders…Give me the rank and file every day in the week…when I rise it will be with the ranks, and not from the ranks.” This followed consistently from many remarks he made over the years, the most famous of which was in 1906, and only paraphrased in the book’s introduction, when he spoke to a group in Detroit. It deserves full exposition:

“I am not a Labor Leader; I do not want you to follow me or anyone else; if you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of this capitalist wilderness, you will stay right where you are. I would not lead you into the promised land if I could, because if I lead you in, someone else would lead you out. You must use your heads as well as your hands, and get yourself out of your present condition…”

The question of legacy

The last section of the book gives the reader a rapid course in the history of “the left” since the death of Debs—some aspects in detail, others get barely a mention, such as the importance of NAM (New American Movement), and its eventual merger with the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee to form DSA. In this section of the book, the complexities and problems of joining history with DSA become apparent. We go through the decline of the Socialist Party, the destructive effects of nationalism during WWI, the rise of Norman Thomas, Michael Harrington, and…Bernie Sanders. I certainly credit Sanders with making the word “socialism” so popular among young people that DSA ranks rose to over 50,000—maybe more by now. But Sanders’ definition of socialism has never gone beyond railing against “the 1%”, and stating that the New Deal, and Medicare represent examples of American socialism. It is here that we see the uncomfortable issue with which DSA struggles, and that is the problematic relationship with the Democratic Party. If we are to return to Paul Buhle’s own questions, “What are the lessons that can be learned?”, I think we would have to say that the lesson Debsian socialism teaches us is that the New Deal, the Democratic Party and neo-liberalism in general have dispensed policies and legislation, sometimes with tangible benefits, but have handed them down from ruling elites, policy wonks and technocrats, to the people, while keeping power and control firmly in their own hands. And as Debs so presciently pointed out, if it is handed down from above, it can, as easily, be taken away—a process which becomes frighteningly imminent with the Trump administration’s evisceration of some of the reforms of the Obama administration. In his Canton speech, Debs said, “In the Republican and Democratic parties you of the common herd are not expected to think. That is not only unnecessary but might lead you astray…They do the thinking and you do the voting. They ride in carriages at the front where the band plays and you tramp in the mud, bringing up the read with great enthusiasm.”

The issue, I think, especially for contemporary newcomers to the idea of socialism, is really about the meaning of socialism. Educating these newcomers should give them the ability to fight back against the attacks on socialism from the right, in a way that can attract, not antagonize, people who might be potential allies. For this task, they will need the ability to distinguish socialism dispensed from above (either in left wing authoritarian societies of the Stalinist variety, or in liberal policies of the Democratic or social-democratic parties), from socialism created from below, the socialism of rank and file actions on the part of today’s working class and their allies. These would be teachers, hotel workers, airline workers, healthcare workers, fights for union democracy, and the mobilization of people in blighted urban areas, in the rust belt, and among women, and within the LGBTQ communities. The socialism of Eugene Debs teaches us that socialism is not just a party platform, or a liberal policy, nor even merely control of the means of production, but is the activity of people in the process of achieving their own freedom, and their own spiritual growth, as they transform society. The book includes, at its end, a list of books for further reading. To that list I would add the as yet unparalleled Two Souls of Socialism, by Hal Draper.

That being said, this Debs graphic biography is important, and will be valuable to young and old readers alike, as it enriches a history that shouldn’t be forgotten, but must be built upon. The book offers a treasure trove of American socialist history, and will spark important discussions about socialism, and the relationship of social theory to social and political activism—this, I think, is the book’s primary goal, and one that it has masterfully achieved.

*Other books in this series: Red Rosa, The Young C.L.R.James, The Beats, SDS, Emma Goldman, A People’s History of American Empire.