Flow is made up of trust and information. Flow is the state in which we are aligned with life, where things are effortless, individually and with each other. When there is enough trust, we constantly rearrange what is happening, in small or large measure, in an endless dance of integrating new information. New information can be just about anything: a new need from within or from without, an event happening, someone’s action has an impact on someone else, we run out of something. The process of integration is many small or large decisions about what to do next given the new information. Specifically, given the current configuration of the information, we decide how available resources would flow to known needs with the least amount of impact. Usually, we make those decisions based on existing agreements, including implicit ones. When no specific agreements that cover the particular situation exist, we base the decisions on our general agreements such as values or purpose, and sometimes we just lean on intuition.

The dance of flow is cared for by three systems: resource flow, information flow, and feedback flow. They are three of the five systems that every group, community, or organization needs in order to function.1

Invariably, a moment comes when we just don’t know what to do next. None of the existing agreements cover the situation. Maybe we look at our values and we are still unclear. Maybe several pathways are consistent with purpose and we don’t know which one to choose, or even how. Maybe a major impact happened, and we don’t know how to create the conditions for metabolizing it into learning. Not knowing what to do next, and not having a clear pathway for discovering that means that the flow is interrupted.

Flow can also be interrupted because of loss of trust. There may well be agreements that are enough for the moment if there were trust, and the loss of trust could lead to the agreements themselves not being trusted. Maybe there is a difficult impact large enough that existing mechanisms of feedback crack under the weight of it. Even if pathways exist in theory, and even if some of us see them, pointing to them and inviting others to follow them can further entrench the mistrust. This, again, means that, collectively, we don’t know what to do next, and the flow is interrupted.

Returning to flow: the basics

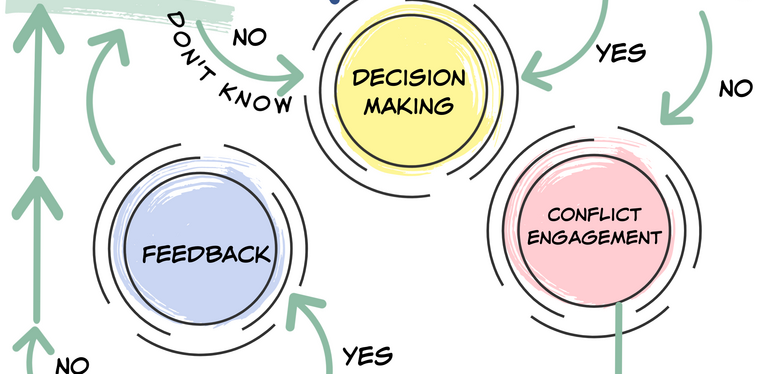

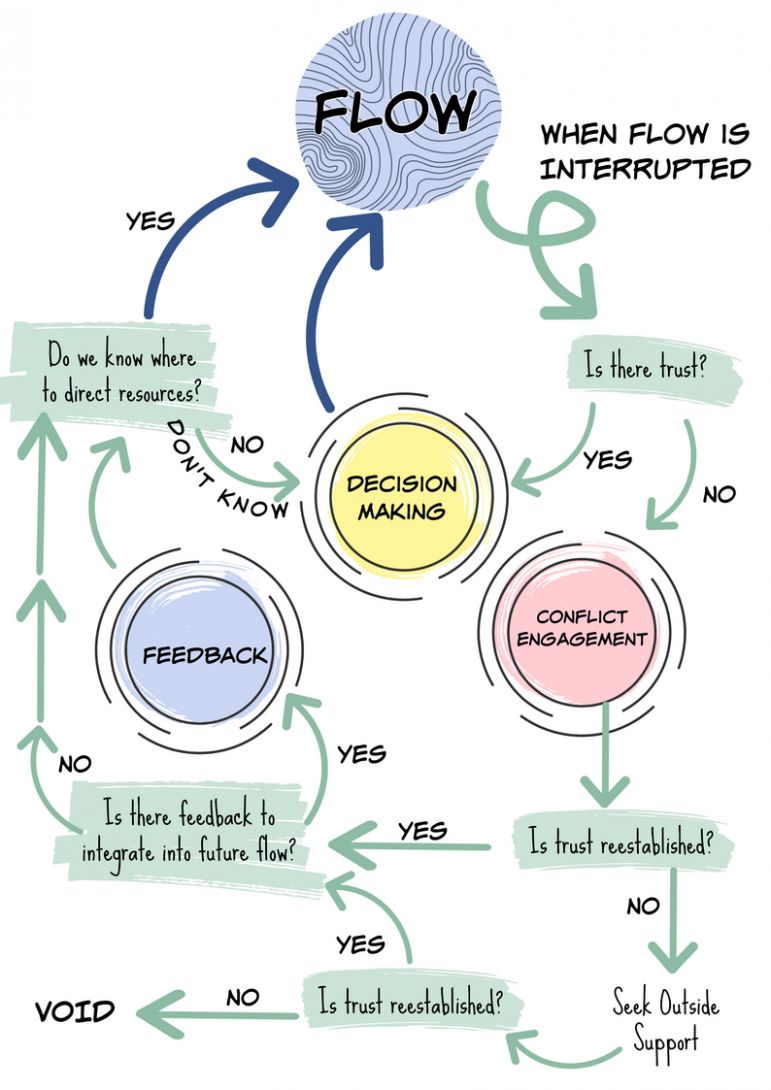

In an oversimplified way, when flow is interrupted, we need to activate either the decision-making system or the conflict system. It’s not like there aren’t decisions within flow. We make decisions all the time, and this is one of our amazing capacities. We make them within the agreements that sustain our flow, which include looking to values, purpose, or intuition to make the decision. The purpose of a decision-making system, as I see it, is to provide pathways for making decisions when we are outside flow already. This means that the amount of information to be decided about overextends existing flow agreements.

Similarly, we also deal with would-be conflict within flow, and we handle it by giving each other feedback, learning, adapting flow agreements as needed, and continuing on. As I see it, the purpose of a conflict system is to create the conditions to metabolize conflict that has overextended existing flow agreements so as to transmute the conflict into feedback by restoring trust and gleaning all the information in it.

How do we know which system to activate? Again, to oversimplify: if there is enough trust to engage with the information, we activate the decision-making system. If even that little bit of trust isn’t there, we activate the conflict system.

You may have noticed that this, in itself, is already a decision to be made: is there or is there not enough trust? Who makes that assessment, and how, is a separate question to which I return in a future post. For now, I want to walk through the steps of how we return to flow sidestepping the question of how we actually make the decision about which of the steps to take.

Decision making

We activate the decision-making system when we face decisions that we don’t already know how to make. For decisions that we are already clear about, we just make them, within flow. We are likely to have clear agreements about how to make certain types of decisions, such as who coordinates a decision-making process, who participates, who gives input, who finds out about it, and who prefers to be out of the loop. You can see an example of what such a set of agreements can rely on here. And those are not the kind of decisions I am talking about here.

The decision-making agreements I am talking about here are those that can guide us on how to make decisions that are outside flow. These agreements rely on the information about decision making that is within flow. For example, if our decision-making system calls for activating a Convergent Facilitation process under certain conditions, we are likely to use the agreements about decisions that are within flow to know who to invite to the process. This is because those agreements provide an approximation of who might be impacted, who is likely to have expertise, and who may have resources needed for implementing any decision in the area we are in.

Once we are within any decision-making process that was activated, we enter flow within it. Again, in this example, once we started a Convergent Facilitation process, we are in it until it’s done. It has its own flow in the sense that information within it is integrated. And, like all flow, it runs the risk of breaking down if trust is sufficiently low. So long as trust persists, we integrate the information that arrives during the process until we reach a clear decision about what to do. The outcome of the process can be seen as a set of agreements about where and how to re-enter flow.

Why conflict

One way of describing conflict is that it points to a situation in which the level of trust is low enough that feedback cannot be shared as a way to attend to the situation before it becomes a full-blown conflict. For any situation to require activation of the conflict system, all available mechanisms within flow, by definition, have been exhausted. This could mean that maybe the available resources are insufficient to attend to the known needs without creating further impacts and at least some people get paralyzed. Or maybe the severity of impacts is bigger than the feedback agreements make possible to metabolize. Or maybe trauma somewhere creates sufficient stress that even a small degree of disagreement about how to proceed can evoke serious disconnection. Or maybe internalized oppression in the context of power differences leads to some people losing their sense of agency, and/or some others exercising power over others. There is nothing in any disagreement in and of itself that creates conflict; it’s only the relationship between the nature of the situation and the available pathways for attending to it.

For as long as we have enough agreements that attend to enough kinds of situations and that are sufficiently within capacity, we are likely to have little conflict. No doubt, this sounds ideal given the chronic low trust within which so many of us live most of the time in our current global configurations. Those of us within the Nonviolent Global Liberation (NGL) community who have been actively experimenting with agreements within the Vision Mobilization framework have had experiences that led to two preliminary conclusions that are still startling for us. One is that we have conscious choice about how much conflict we have. The other is that calibrating the degree of conflict for different priorities and purposes is more useful on the long journey to liberation than automatically aiming to prevent or reduce conflict.

A full exploration of what the considerations might be is something I want to come back to another day. One simple principle is that when we want to create change, we are likely to need to generate more conflict to make new integration possible, however odd it may sound that generating conflict could possibly be something we would want. Conversely, when we want to integrate and rest, we are likely to need to calibrate agreements more to existing capacity to reduce the amount of conflict.

For inner change, when we want to pull our collective capacity more towards vision, we may make our agreements more aspirational, so that we can be called upon to integrate our values more fully into our way of functioning through the conflicts that will then likely ensue. Similarly, for outer change, when we aim to create change in an external system that we perceive as oppressive or threatening of life, we may move towards more conflict with some segments of society.

Nonviolent resistance, for example, can be seen through this lens as a refusal to continue to uphold agreements that may appear smooth to those in power while being at high cost to others, cost that is also often rendered invisible unless we embark on noncooperation or direct action. Given the immense gap between our current collective global capacity and the vision of a world that works for all, in order to sustain our capacity over the long haul we will also need to have periods of sufficient rest from conflict to be able to mourn, learn, and nurture ourselves to be able to recover sufficiently for the next leg of liberation. I mourn deeply just how little rest from conflict I have seen in activist communities, and I suspect that not attending to this need for rest is key to why so many people burn out so quickly.

Part of the tragedy, that all conflict systems need to reckon with, is that all of us living now, almost everywhere, carry within us impacts from thousands of years of patriarchal systems filtered through our own individual socialization and compounded by the impacts of being in whatever specific social location we are: our class, our ethnicity, where we grew up, our gender, and so on. We bring this individual and collective trauma with us anywhere we go, and it results in heightened mistrust. Many more situations then result in some degree of would-be conflict than our flow systems can metabolize; more even than most conflict systems can support us in metabolizing. Our current conclusion is that, overall, those of us currently working for change need to put concerted efforts into creating systems, in all areas, with agreements that are much closer to capacity than aspiration if we want to sustain capacity over time.

Conflict engagement

Once the conflict system gets activated, it has two functions. One is to restore trust, and the other is to support learning by releasing the information stored within the conflict that was previously unavailable because of the low trust. Sometimes it only takes all parties being heard to restore trust, and sometimes it requires substantial action to undo the effects of sustained oppression, and anything in between. It is vital for the trust to be restored, as much as possible, before attempting the learning.

Restoring trust may only take all parties being heard, may require substantial action to undo the effects of sustained oppression, and may be anything in between. Sometimes, restoring trust may take a generation or two if the impacts are deeper than the capacity to create change.

The field of conflict engagement is extensive, with a vast literature that is fully beyond the very particular focus of this piece. Still, some words seem essential in relation to one layer of complexity, which is that many approaches to conflict end up easily reproducing the existing social order, while in all I write my commitment is to plant seeds for a visionary future, water them with every experiment in applying them, and describe the resulting learning in further writing.

Because of this particular complexity, I want to call attention to Restorative Circles, a systemic approach to conflict initially observed and described by Dominic Barter in Brazil, which is now an open field of research on all continents. Similar to Paulo Freire’s approach to popular education, which he called “critical pedagogy,” and Manfred Max-Neef’s approach to economic development, which he called “human-scale development,” Dominic’s work with Restorative Circles engages a community or organization’s latent capacities. Nothing is imposed; there is no set method; and the processes and agreements emerge within the community. In his words: Restorative Circles “develops the dialogical conditions for unique local practices emerging out of endogenous community wisdom.”

I am mentioning this here for two reasons. One is that I see Restorative Circles as a significant example of applying vision in the world as it is, without waiting for conditions to be perfect, simply by focusing on sufficient local conditions. The other is to support humility for all of us. After 25 years of participating in, inspiring, witnessing, and supporting work in 50 countries, with enormous visible and transformative results, Dominic cautions us that many of the systems that came into being have both struggled to survive and, because of accepting heavy-duty compromises, some of them end up “effectively sustaining the policies they were implemented to change, by absorbing painful conflict rather than facilitating its progress into transformative action.”

What I learn from this is that we can’t assume that just because we are committed to some version of the vision of a world that works for all we would ever be immune to what Dominic calls “punitive drift.” For me, this is an ongoing reminder that our vision needs to be anchored in sufficient agreements to serve as counterforce to this drift. As I see it, one part of why conflict is so prevalent in movements and communities committed to a transformative vision is because we don’t usually put in enough agreements to care for the gap between our commitments and our capacity. In the absence of enough agreements that specifically anchor our vision, we default to patriarchal conditioning, both individually and collectively. This is part of what I see as the function of a transformative conflict system: to provide a context where our conditioned responses are revealed to all of us, and we can then hold together the tragedy that befell us, globally and wherever we are, so that we can take the next step in the direction of vision. This, again, is why we need to restore trust before the learning can be effective. Without it, our learning will be far less effective, and we are too likely to remain immersed in reaction, especially in shaming self or other, and less able to simply look at the specific phenomena in operation.

At the time of writing this, a group of us engaging in a 3-month community experiment in Portugal are in the process of putting together a new conflict engagement system that began to emerge in the last months from hard-won insights from previous experiences of being involved in many conflict fields and being overstretched by them. There are many reasons why conflict fields can overstretch us. In my own case, there is personal trauma history of immense criticism, bullying, and more, and there is the reality that being in a leadership position means more people engage with me and there is likely to be more conflict because of the nature of the work being visionary and raising lots of hopes for people that are then dashed. And, beyond my personal experience, the core insight is systemic.

We are now questioning the prevalence of the assumption that conflict processes require people to hear each other’s full expression to (re)establish trust. We are questioning it from the capacity lens: within conflict, everyone’s capacity, both to speak and to listen, are heavily compromised. Our preliminary idea for the conflict system arises from the center of the capacity perspective: conflict, and lost trust, are indicators of low capacity. This leads to the new approach we are beginning to experiment with. When a group, family, organization, or community faces a significant conflict, we are now looking for and systematizing ways in which anyone, regardless of their involvement within the conflict, can bring exactly the capacity they have to the whole in service to increasing capacity. In this way, we believe, trust is restored to the extent that there is enough capacity within the system to digest what has happened that led to the conflict and make visible and usable the information stored within the conflict.

Integrating new information

The information that is made newly available after restoring trust often reveals the incapacity in the other systems, both the flow systems (including resources, information, and feedback) and the decision-making system. Once the incapacity is known within a field of trust, learning can happen. Such learning is not interpersonal, though it may contain interpersonal bits that would need to be embedded within agreements to match them to actual capacity. Mostly, such learning is about where agreements may have been either too aspirational or missing altogether, leaving gaps that feed the incapacity and the mistrust.

When I have introduced groups of people to the five-system model, often they take out their notebooks and start writing extensive notes when I talk about decision-making, and often they get lost when I get to talking about conflict being, in part, a pointer to systemic gaps. The idea that conflict is an interpersonal phenomenon rooted only in personality differences, communication styles, or psychological issues is so deeply entrenched that the systemic lens is largely invisible. A particularly significant moment in my own capacity to see and show the systemic context from within which conflict often arises, was when I heard Marie Miyashiro give a brief introduction to the framework she developed to work with organizations, called “Integrated Clarity,” in which she used an example of how a blurriness in decision-making can be the source a conflict that could reappear in a different spot even as each instance of it is “resolved” at the interpersonal level. That insight stayed with me and was perhaps one of the reasons why I was able to address a conflict I was asked to facilitate with such dramatic success.

I was called into a high-tech startup company by the CEO to see if I could help him resolve a conflict between two of his top executives. He valued both of them for the work they were doing and was beside himself thinking he would have to lose one of them because of a conflict between them. He was quite certain that there was a personality clash and was reluctant to invest a lot of energy into it. He asked me in as a kind of last resort, pretty much assuming I would confirm his worry and support him in bringing about the painful closure he dreaded.

Instead, what happened was a near miracle for everyone involved. I met with each of the two executives for 30 min each to understand their picture of what was going on. By the end of the 2nd meeting, I had zeroed in on what I thought was the core issue, locating it in blurry lines about decision-making. One of the executives was VP of product development, and the other was VP of IT services. Given that this was a high-tech company meant that the product itself was tech-based, and there were no agreements about many decisions. Once they were both sitting together in the office with me, I asked them, together, a few more questions, and my diagnosis rang entirely true to them. Not too long afterward, we had a simple proposal to offer the CEO. We invited him in, made the proposal, and 30 min later we had the problem addressed. The solution was so simple I was almost embarrassed to make it: a weekly meeting including a representative from each of the two departments with the CEO to review all decisions that were in the blurry areas. He agreed. The whole thing took less than three hours. The last time I checked, three years later, both executives were still there, and no further conflict had arisen between them. Neither of them had to make any personal changes or adopt any new practices. Despite the intensity that the conflict presented, it was entirely based on a gap in the decision-making system. Once the gap was filled, the conflict evaporated.

Because each conflict is unique, we cannot ever predict, before engaging with the conflict, what it contains within it. Much of the potential of conflicts to move us closer to vision through increasing capacity and/or contributing to change gets lost when we hold a picture of what’s commonly called conflict resolution. Conflict resolution tends to focus only on the restoration of trust and only on the interpersonal, without looking for the information that usually awaits afterwards about gaps in other systems. I made that error many times myself, confusing the release of tension and visible sense of connection at the end of a process such as mediation with the idea that the conflict was over, only to see it resurface hours, days, or weeks later as the conditions that gave rise to it were not attended to. I believe that Marshall Rosenberg contributed to this lack of understanding when he said, many times over, that whenever both parties to a conflict have fully understood and can reflect their understanding of each other’s needs, the problem can be solved within 20 minutes – and then didn’t demonstrate what it would look like to find actual strategies to attend to the source of the conflict, nor emphasized sufficiently just how vital it is to do this. If not for Dominic Barter, who brought Restorative Circles, and with it the results of many years of experimenting and learning in Brazil, to the global north NVC communities, we would still not see it. He showed many of us the danger of attending to conflicts solely through relying on momentary connection that isn’t anchored in decisions about what comes next.

The desert community experiment three of us engaged in in the fall of 2019 was a leap in understanding about engaging with and learning from conflict. We were in a no exit situation, and there was simply no option of walking away from conflict. I wrote about this experience in an earlier post called “Liberation Lessons from the Desert.” The repeated experience of seeing that each conflict we engaged with led to new or changed agreements, and seeing how, over time, slowly, we had longer stretches of flow between conflicts, laid a strong foundation for the vagabonding and for all the community experiments since. These experiments and their results are the main reason why the flow chart that accompanies this post includes checking about feedback integration before going back to flow. Any conflict well-metabolized contributes to increased function.

(Diagram by Selene Aswell, based on conversation download with me)

Before moving to resuming flow, I want to acknowledge that I am writing about conflict and about conflict systems, an area in which I’ve had many conversations with Dominic Barter about the work that he and his colleagues have developed in Brazil. When Dominic has brought Restorative Circles to the global north, much of what has unfolded has followed deeply grooved global patterns of “cultural appropriation.” Because part of the challenge of such patterns involves disputes about the nature and extent of influence, and because Dominic and I have had many conversations about his work, none of us have any way of knowing, in this case as well as others surrounding our work within NGL, whether and to what extent the pattern is active in our experimentation. Even as the main focus of our experiments has not been about conflict, we have still had to bump up against conflict and have had to learn about it while engaging with the work we are focusing on about purpose and values; work from which arose the Vision Mobilization framework. I want to name and mourn this inherent inability to know and its impacts, and to surrender to the overall tragedy of the vastness of global patterns that keep us from sufficiently being able to find trust and learn together, everywhere.

Resuming flow

After all new information is integrated into revised agreements, and once we have a clear entryway back into flow, it is a distinct pleasure to see how often the revised agreements support better flow for all, including often for those who may have resisted them for some time. This pleasure is a source of energy that is part of what sustains me through the harder times.

I have yet to experience engaging with conflict as pleasure. I do, however, experience pleasure in the process of making decisions with others even in moments when we look at a pile of needs and impacts and don’t see a way for the resources to flow well towards the needs, either at all, or only with more impacts than we would want to accept. I still enjoy it because I usually have sufficient trust that one of us will eventually come up with a pathway, or we will mourn our lack of capacity and accept, together, a less-than-ideal outcome. Like all living beings, I thrive on flow. Flow, for me, is like flying, gracefully making decisions with people in such flow that it almost seems like we are just one person. As my trust in life itself continues to increase, perhaps a day may still come that the knowledge I now lean on based on pure will – that a conflict well-engaged with yields greater capacity – might seep into my cellular makeup and I can stay fully alive and confident even in the midst of conflict.

REFERENCE

1 – If you are interested in understanding more, you are invited to read the “Aligning Systems with Purpose and Values” section of the Nonviolent Global Liberation website before continuing. Any reference to the “five system model” or to five systems is to this configuration.

PHOTO CREDIT

Student Pyramid by Josh Berglund on Flickr