Bounding up the stairs of Wrightwood 659, a stark, modern, three-story gallery in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood, I am waylaid by a painting of two men at night in front of a brick walk-up. One of the men wears a mask and holds a putter. The other is seated, wearing a Black Lives Matter t-shirt. A hollow-eyed rat surveys the scene. The uncanny setting reminds me of something from my own life, but I’m not sure what. I move closer and breathe in the aroma of the oils. The surface of the painting seems to glow from within.

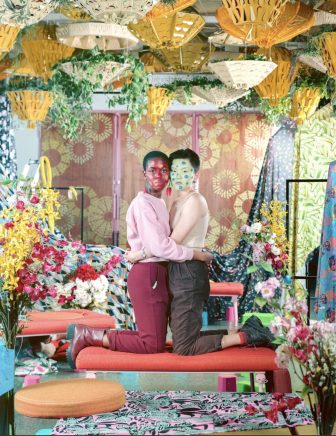

Leonard Suryajaya, Two Bodies, 2017, Archival inkjet print, 50 x 40 in.

Upstairs I hear the start of the artist’s talk for which I am now late—it’s the opening symposium of About Face: Stonewall, Revolt and New Queer Art. The painting that has frozen me in my tracks is one of the 450+ works that are on view in the exhibition, which spotlights an international, inter-generational, interracial, multi-gendered roster of more than 40 queer artists.

I tear myself away from the painting and hurry up to the symposium. Afterwards, I am introduced to the painting’s maker: Attila Richard Lukacs. He tells me the story of the painting. The man in the mask is him, and the man in the chair was a dear friend. A few days after Lukacs finished the painting, his friend died.

The more Lukacs tells me about his life and work, the smaller I feel for some reason. There’s no doubt I connected with his painting, but the more I know about its narrative source, the less proud I am of my reaction to it. I usually report on abstract art. It’s my comfort zone, so even though this painting was clearly telling a story I connected not with the subject matter, but with the formalist aspects of the art object—the texture, the color, the medium, the light, the scale. I buy in to the notion that these plastic elements are universal; that keeps me at arm’s length from the subjectivity and personal emotion of the artist.

I perused the exhibition again, this time trying to look beyond the plastic elements to see what else is in the work. Afterward, I met Jonathan David Katz, the exhibition’s curator. I told him about my experience, and he reassured me—the impulse to assign universal status to personal perceptions is human nature.

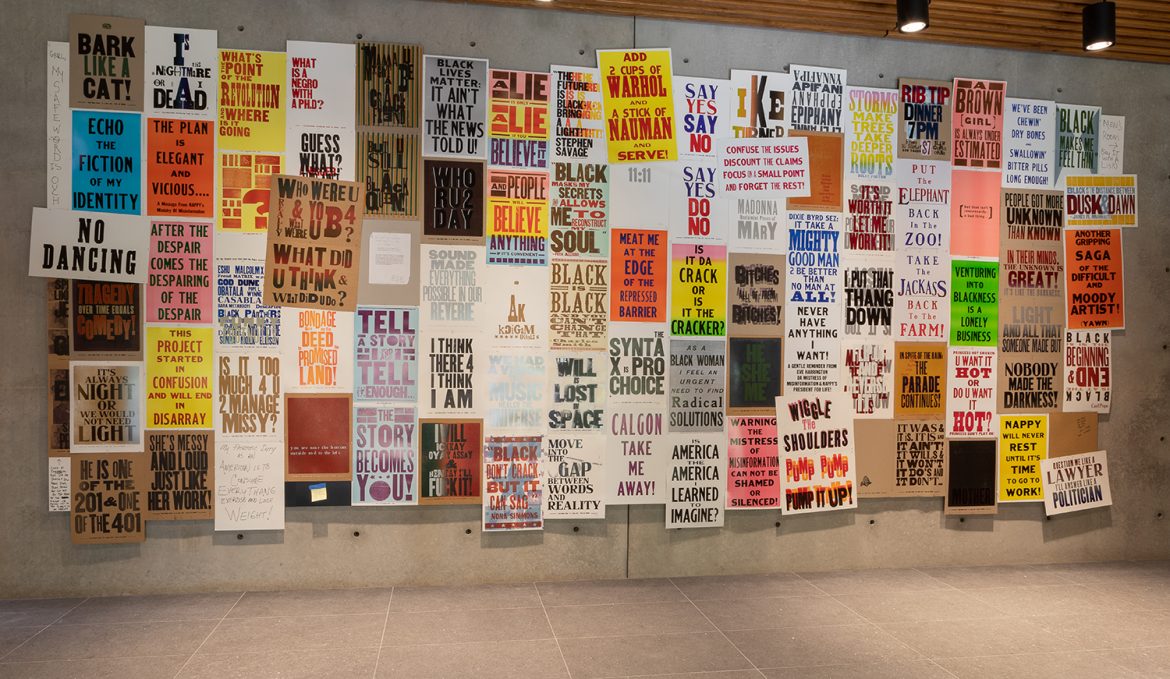

Installation view of Deborah Kass paintings.

“There’s a great deal of seductive power to the idea of the universal,” says Katz. “One always wants one’s perspective to be writ large. It makes one feel at the center of the universe. But to claim a universality that doesn’t first other is to claim a universality that’s written in the image of power and authority.”

Katz calls this “constructive othering.” In the context of a painting, it means acknowledging that status of the artist as an other, and not just colonizing their work by claiming the viewer’s entitlement to impose meaning on it without first seeking out and respecting the subjectivity of their perspective. That’s a tall order for an art critic. But constructive othering fascinates me—it’s subjectification over objectification.

“In order to get past our differences,” says Katz, “we have to acknowledge them. In order to create a world of equality of opportunity, we need to acknowledge there are certain individuals who, by virtue of birth, have greater access to that opportunity. Then we have to self-consciously build rectification of that system.”

Katz hopes the wildly different perspectives he has assembled in About Face will take the viewer through a journey of subjective experiences of the world that will work to decenter any residual universalism they may have about their identity, in favor of what he calls “a much firmer foundation in a different kind of universality—the universality of our most basic needs.”

This way, he says, we can become invested in trying to understand not identity, but identification.

Identity is a passive acknowledgement of where one comes from, or as Katz calls it, “The re-ification, or self-satisfied stasis of where you are by an accident of genetics and circumstance.” Identification, he explains, is an active role of empathy, “that allows us to find, despite our differences, points of commonality. If we build a politics based on identity, we will only reinforce differences. Identification will allow us to bridge them.”

As a cis, white, hetero male touring this exhibition, I found myself confronted at almost every turn by opportunities to identify. More than once, this process made me feel less alienated; less alone.

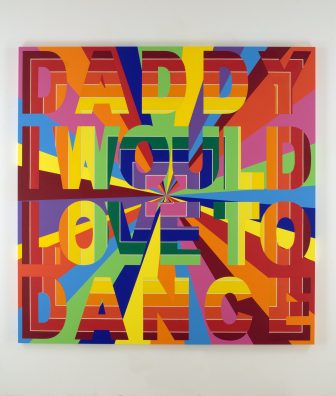

Deborah Kass, Daddy I Would Love to Dance, 2008, Acrylic on canvas, 78 x 78 in

A lovingly personal Keith Haring painting made me aware of the humanity I had not previously acknowledged in his oeuvre; a rare photograph by Harvey Milk delighted me, and cured my total ignorance that this first openly gay American elected official also nurtured an art practice; a Soundsuit by Nick Cave vividly animated for me the terrain separating identity and identification; while works by Deborah Kass, Tianzhou Chen, Carl Pope, Roger Brown, and several others, made me laugh out loud with their wit-filled manifestations of the multitudinal self.

The next night, New York-based multi-media artist Keijaun Thomas staged a performance in the atrium of Wrightwood 659 that made crystal clear what Katz had told me about Constructive othering. Thomas invited people of color onto the green where they were served wine and water solicitously while white people were told to turn away and face the walls. As privilege was assigned and then weaponized, individuation disappeared before the audience’s eyes.

Says Katz:

“At first during Thomas’ performance, like a lot of white people, I was distressed that so firmly was my race made a marker of my politics and identity; that I was assimilated into my race. But as the performance went on, it became clear that this is a social and political reality that people of color experience daily. Not only was what I was feeling empathetic with what they experience, but it ended with all of us who were present entering the green and avowing each other with an affirmative hug.”

By directly acknowledging, and then moving beyond an artificial cultural separation, Thomas plainly contextualized the opportunity Katz faced as he planned this exhibition to mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots—the series of violent demonstrations that began on the morning of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York, which helped spark the contemporary LGBTQ rights movement.

“With my curation, I really wanted to push back against what I felt were historical inaccuracies in the account of Stonewall,” says Katz, “which have tended towards understanding that moment as the beginning of a binary account of sexuality, the birth of gay and lesbian cultural separation. The queer movement has been dedicated to erasing borders and boundaries, towards eliminating the idea of a binary schema, resting on the idea that sexuality is not a significant or profound difference between people. Secondarily, the idea of the refusal of an oppositional schema seemed particularly apt at this historical moment, as we have a president who seems invested in separating everyone he can as a tool for cynical politics. I wanted to push back against historical inaccuracy and evil cynical politicking.”

Kent Monkman, Installation view of Dance to the Berdashe, 2008, Five-channel video and mixed media installation, dimensions variable

The name of the exhibition embodies his hope for an existential turnaround.

“We wanted a title that suggested a shift or a change at Stonewall,” says Katz, “but one that didn’t reify the notion of a divide. About Face suggests a turn—broadly from shame to pride—but doesn’t specify what that change entailed. And I liked the punning on face, and its connection to voguing, a movement that seemed to me to emblematize the inclusive politics of a very queer political difference, one in which, say, African American socially marginal men could compete over who did the best rich, white woman.”

Also essential to Katz’ curation is a total embrace of sex positivity.

“I wanted to use sexuality in a way that sought to counter the notion so often in evidence in museums that heterosexuality is the universal norm and it goes unremarked,” says Katz. “You can look at countless images of female nudes from a hetero male perspective and that’s considered classical. I wanted to create a bubbling cauldron of queer sexuality in all of its guises that immerses one in the notion that this is normative sexuality in all of its phases. The great thing about Wrightwood 659 is that this wasn’t a problem. I’ve curated shows in other institutions in which it was a problem, because they allowed outside forces to manipulate the politics around the exhibition. For example I did the exhibition Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, which was at the Smithsonian, and the Catholic League and its mindless minions attacked the show for what they said was its anti-christian purposes.”

Wrightwood 659 façade. Image courtesy of William Zbaren.

What upset them, says Katz, was that it was a queer art show being validated by the mainstream.

“Suddenly they realized that objecting to queerness wasn’t going to pay dividends in this contemporary political environment, so they shifted their attack and called the show anti-christian. Enemies will mutate as required in order to attack what is, in the final analyses, the key objection, which is having a museum lend a platform to the other and otherness. It just seems to me clear evidence of the fact that they recognize how endangered their position really is. Rather than seeing these attacks as evidence of my vulnerability, I see them as evidence of our power.”

About Face: Stonewall, Revolt and New Queer Art is on view at Wrightwood 659 in Chicago through August 3rd, 2019.