How can one understand the importance of the philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas? Jacques Derrida in his eulogy at Levinas’s memorial service explained it as a certain bending. Levinas started as a translator and expositor of phenomenology and ontology but gradually bent these philosophical systems in the direction of a certain form of Judaism and an ethical responsibility based on otherness and difference, not on sameness or commonality. This bending not only permeated philosophy but many other academic disciplines and even affected culture in its many forms. For a few Levinas-infused decades, there was much talk about otherness and how to find more ethical ways to orient ourselves to all kinds of differences such as ethnic, religious, and sexual.

To what extent Trumpism—which is both essentially anti-Semitic and a refusal and even mockery of the very idea of ethical responsibility—has succeeded in bending our own American culture back in a direction quite opposite of Levinasian ethical responsibility for otherness is a question that presses upon all of us now. In most of America it takes only one trip to the grocery store to convince you that most Americans at this point are just so done with all this ethical responsibility to others!

I agree completely with Derrida’s view of Levinas’s work as an extremely powerful bending, but I am sure he would also agree that even that does not exhaust the importance of this work. The majority of Levinas scholars agree that his philosophy is radically affected by the Holocaust, that it is a philosophical response to the Holocaust, and in some way the Holocaust is always present in his philosophy. They would say, along with Robert Eaglestone, that the Holocaust “suffuses” Levinas’s philosophy and that his response to it “is enacted in and by his philosophy.” Yet Eaglestone himself and several other Levinas scholars are also honest enough to say that even as we argue that Levinas is a post-Holocaust philosopher, he hardly ever mentions the Holocaust in his major philosophical works. Compared to other post-Holocaust philosophers such as Adorno, Fackenheim, and Rubenstein, he simply does not write much about it. As a result of this paucity, scholars are led over and over again to the same short text, the 1982 Levinas essay about the problem of theodicy, “Useless Suffering,” the one place where Levinas does directly discuss the Holocaust, Auschwitz, the final solution.

This issue of the Holocaust in Levinas’s philosophy is an important and perplexing problem. It is, in fact, rather confounding. The philosopher many of us would say is the most powerful post-Holocaust philosopher is at the same time a philosopher who only rarely mentions the Holocaust. One way to make sense of this is to look for traces or images of the Holocaust in his major works. A perfect example of this is what Robert Eaglestone says about Levinas’s discussion in Totality and Infinity of the importance of good soup. Eaglestone eagerly grabs on to these passages because he claims they show how Auschwitz and the death camp experiences are revealed in Levinas’s work. However, the reality is that Levinas spent five long years in POW camps in Germany during the war, not in Auschwitz; he probably has plenty of his own experiences of the importance of good soup that have nothing to do with Auschwitz or death camps so the claim doesn’t hold up. Scholars search his major works for other images or traces of Auschwitz and death camps—cattle cars, showers, poison gas, Zyklon B, Musselmanner—but do not find them because they simply are not there.

I believe and have argued that approaching the problem of the Holocaust as only Auschwitz and death camps in Levinas’s work is an often-tried hermeneutical dead end. We can make much more progress if we approach the question of what the Holocaust is in a more complex fashion and if we pay more attention than Levinas scholars usually do to the horrible lived reality of his own life.

Levinas, of course, was not in a Nazi death camp but in German POW camps for nearly the entire length of the Second World War in Europe. His long imprisonment is often mentioned by Levinas scholars, but what is mentioned much less frequently, and in many secondary sources not at all, is the horrible reality of what happened to Levinas’s birth family in Kaunas, Lithuania, while he was in the POW camps. His parents, his two brothers, and his wife’s father were all murdered by German Einsatzrgruppe forces and Lithuanian collaborators in the early, Holocaust-by-bullets phase. It astonishes me that several scholars who argue strongly that his philosophy should be seen as post-Holocaust nevertheless do not even mention these horrible murders. If Levinas had been in Auschwitz or another death camp even for a short time, the first thing we would say about him is that he is a Holocaust survivor.

But we can’t say that about him. Although he lived most of his adult life in the Holocaust’s horrible shadow, he was not a survivor in the way most people use that term. Very often, his experience is not mentioned even by scholars who believe strongly that his philosophy is post-Holocaust. They leave out entirely his own very painful and traumatic personal relationship to what Levinas himself often called “Holocaust horror.”

Part of the reason scholars don’t mention this fact is that he himself does not talk about it. Aside from the dedication to his murdered parents and brothers and in-laws at the beginning of Otherwise Than Being or Beyond Essence, Levinas never mentions what happened. His biographer and close friend, Salmon Malka, after lengthy conversations with Levinas’s own two adult children, Simone and Michael, states: “The whole family was annihilated, the grandfather, the grandmother, the two uncles, Boris and Aminadav. Levinas never spoke about it. Not in his writings, not in conversations with friends, not even with his family. It was an open wound in his core, a deep wound.”

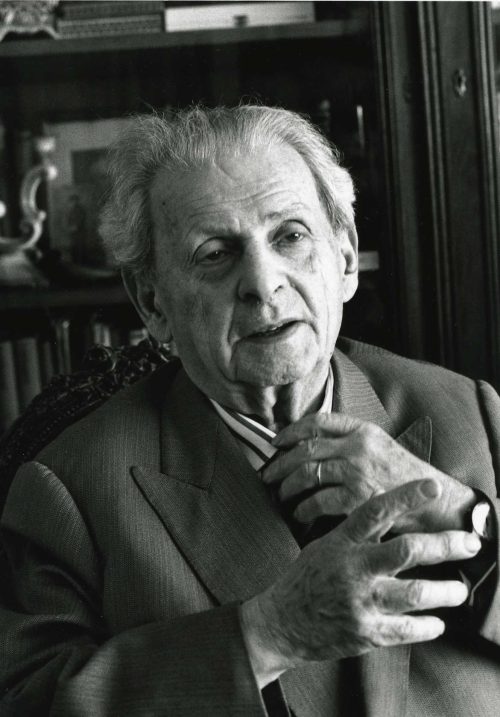

When I was finishing my dissertation on Levinas and Heidegger, I wrote to Professor Levinas and he wrote me back (actual letters!) and kindly invited me to come to Paris to talk to him. We met three times in his apartment in November of 1989. Levinas told me that because of the Shoah he vowed never to step foot in Germany again, a vow he kept. I wanted to ask him about Lithuania. I hesitated and never did. How could I bring up such a painful subject with a kind, older gentleman who was offering such gracious hospitality to a young American stranger?

I have become convinced that if we read Levinas’s philosophy and think of the Holocaust as Auschwitz and death camps, we get nowhere. But if we think of the Holocaust in a much broader way, the way it often was in its earlier phases in Kaunas, throughout Lithuania, and in so many other places—sudden, hateful, murderous violence—and if we ask if there are images or traces of this Holocaust in Levinas’s philosophical work, we have to say that there are many such images and traces.

We start with Levinas’s first philosophical classic, Totality and Infinity, a beautiful tribute to the face of the other person and the command to ethics, goodness, justice, and peace. Levinas can be a maddeningly repetitive philosopher. He repeats this call to ethical responsibility over and over, dozens, maybe even hundreds of times in Totality and Infinity, but within this constant repetition are several startling passages about hatred, physical violence, and murder. He posits that hatred desires supreme suffering in murdering the other. The face of the other also tempts me to murder. Fear of death is not just fear of the mortality I cannot escape. It is fear of being suddenly seized and murdered. “Murder, at the origin of death, reveals a cruel world, but one to the scale of human relations.” The language about sudden violence and murder is not repeated dozens of times, but it is there as a constantly haunting, ominous presence.

The great later work, so different, so strange in so many ways, Otherwise Than Being or Beyond Essence is perhaps even more haunting, more ominous. Here Levinas largely abandons beautiful tributes to the ethical meaning of the face; he tries to describe what evades all description or explanation, the anarchic nature of ethical responsibility prior to the self’s own choice or decision. To make this argument Levinas uses such an extraordinary set of metaphors that Paul Ricoeur asked in exasperation “Why such extreme terms?” Ricoeur of course was asking about the extreme, violent language in this later text: “hostage, sneaked in like a thief, persecution, trauma, hunted down, hunted down even in one’s own home, other in one’s skin, the trauma of persecution.” There is so much traumatic and violent language in Otherwise Than Being or Beyond Essence that Ricoeur referred to it as “verbal terrorism.”

Why does Levinas describe how the self comes to be ethically responsible with such haunted, even violent language? I admit that I have wondered all these years since I met Levinas how what he called “Holocaust horror” lived within him. It is a question about what he referred to only once as “a tumor in the memory.” I do believe that tumor in the memory had a great deal to do with sudden, hateful violence of eager collaborator and Einsatzgruppe horror. I do think we can hear, see, and feel images and traces of this violence and horror in Levinas’s great and extremely important philosophical works.

What I have come to believe about Levinas’s philosophy is in a way oddly mirrored by what has been happening in Kaunas. I did some volunteer teaching of English in Kaunas in the summer of 1997 because I wanted to live at least for a few weeks in Levinas’s city. I also wanted to go to the forts on the outskirts of the city, sites of the massacres of Jews by the Nazis and by their Lithuanian accomplices. I felt in some way I owed that to this great philosopher who had been so kind to me. By the time I was in Kaunas—a not large but beautiful city, eager for increased visibility and tourism in the new Lithuania and European Union—Levinas was quickly becoming more famous. I remember wondering back then what would happen if this city one day decides to publicly commemorate its perhaps most famous citizen? How does a city commemorate a famous citizen when some of the people in that city helped murder the parents and the brothers of that same famous citizen?

This is exactly what has been and is happening. There is now the Emmanuel Levinas Center at the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences in Kaunas. This endeavor was supported by Levinas’s daughter Simone, a physician, and her son, David Hansel, who spoke at the celebration for the new center in December 2021. On this occasion, the Hansel family recognized the heroic efforts of Dr. Ona Jablonskytè-Landsbergiene, one of the Righteous Among the Nations, who hid and saved the life of one of Levinas’s aunts and whose daughter is a physician and administrator of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. One can easily imagine what an amazing experience it was for the Hansel family to work with the daughter of this heroic rescuer in the establishment of this center named in honor of their father and grandfather, the great philosopher from Kaunas.

However, Levinas’s son Michael, a pianist and composer, has publicly opposed the establishment of any center in Kaunas bearing the name of his father. In doing so he may help explain what Levinas himself did not explain even when he mentioned his own “tumor in the memory.” These murders of his family, his son says, are why his father refused to return to Lithuania. He insists that the vow Levinas made was not only about Germany, but also about Lithuania. His explanation for his position against what is and has been happening in Kaunas does, I think, shed light on what Levinas referred to only one time as “the tumor in the memory.” That tumor has, I believe, a great deal to do with Kaunas and what happened there. Levinas did not talk about it. But there are, I believe, traces and images of its horror in Levinas’s major philosophical works. It is time for us to understand this as we think again about the many reasons why this man, Emmanuel Levinas, is widely considered one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century.