In 2020, when Emma Quayle and I started vagabonding in earnest, one of our criteria for what we wanted our next steps to be as we journeyed further was “unmasking the impact of patriarchy and allowing us to experience first-hand the intensity of its manifestation.” We intuited what was later confirmed by experience: that we would increase our learning by moving away from the comfort of being embedded within the global North system as residents of one location. What we have learned has deepened our resolve to continue to walk away from existing systems and towards creating an island of interdependent living together with a potent vision of an interconnected global web of visionary communities.

Over the years of vagabonding, one of the most intensive lessons has been seeing more and more clearly the depth and pervasiveness of violence that’s built into the system. Everywhere we look, we see the ways that this violence is exported, outsourced, masked, justified, and even denied in service to the illusion of progress for all. This applies to people, the larger web of life, and all other elements that make up the intricate system called planet Earth.

Mundane violence in a tourist beach town

In October 2023 we were given an astonishing gift of an apartment to live in for up to two years without rent, covering only the costs. The woman who offered it to us is inspired by our work and this is her way of supporting us. The result is that we are living in a place that we would be extremely unlikely to live in under any other conditions. The combination of the extraordinary beauty of the coastline and the extreme instrumentalization that is so characteristic of tourist towns has been an intense daily experience as I take my daily walks.

When I say “instrumentalization” I am not talking in abstractions. I am talking about very concrete, harsh, and material events and actions. Most specifically, I am talking about how plants, who are living beings just like us, are treated. All the housing complexes here are manicured, which means, effectively, that living beings are constantly clipped, pruned, cut, shaped, or uprooted. I shudder, cringe, mourn, despair, rage, and often numb out at the relentlessness with which the intensity and unruliness of life is forced into the shapes that someone decides are what counts as beautiful and fit for the people who come to these towns for a few days or weeks. The hedges are made to be straight, the bushes in the median strip are made to be round, and either way, this brings death upon the plants, not more life. The tender, green, new branches are exactly the ones that get clipped, and it’s the old, brown, tired branches that remain, so the proportion of green keeps diminishing, year by year, month by month. As I walk to the shore, I feel the cry of the plants, as if they speak to me and ask me to do something about it.

Why is life being attacked so much?

Life as wanting and movement

I encountered Nonviolent Communication (NVC) in 1993 and made it central to my life path in 1995. It still took some time before I grasped the fullness of the shift of putting needs at the center of what it means to be human. I can’t remember if it was a gradual process or a sudden insight that finally got me to grasp what Marshall Rosenberg said so simply in an interview: “The needs come because we’re alive.” From there, another crucial step was branching beyond the human into all life, eventually to understand life as the fundamental process of wanting and then moving towards the wanting, endlessly cycling and interacting with all other life, to where I eventually understood life to be “the constant rearranging of everything in the continual integration of all volitions” (from the Realigning with Life article).

Two years earlier, in 2017, I had another understanding that complements this one: “Life is arranged to care for all that lives through an endless interdependent flow of energy and resources” (from Life, Interdependence, and the Pursuit of Meeting Needs).

Volition, that exquisite combination of desire, will, and choice, is that primal energy of wanting that is all life. The flow of energy and resources is the movement. No life without wanting. No life without movement. This is true of humans of all ages and shapes no more and no less than of the plants, animals, fungi, microbes, viruses, insects, arachnids, and all other creatures I don’t even know about. All of us are life. All of us are expressions of wanting. All of us move, all the time.

And there are some things that are unique to humans even as exactly what that is remains controversial. My sense, despite not being an evolutionary biologist, and likely speaking inaccurately, is that the degree to which our behavior is shaped by social learning far exceeds that of any other living being. The variability of human societies, along multiple dimensions, is immense. Knowing this, and having lived in multiple countries and cultures over the course of my life, I am very able to imagine ways of being radically different from what is present in modern, global North countries. This helps me in imagining human societies from the long ago past as possibly very, very different from our own. From all I have read, I have embraced the perspective that for 97% of our existence as a species we lived within life, in trust of this flow, in mostly peaceful and egalitarian societies, and in surrender to the cycles of birth, growth, decay, death, and re-birth, which was understood quite literally.

And then came patriarchy.

Patriarchy and life

Patriarchy, as I have said many times before, emerged from scarcity, which is an expression of loss of trust in life. Such loss of trust arose for specific reasons. When we think about the more recent events such as colonization and the tearing of people away from land and community, enslavement, and witch hunts, we can point to specific people who did specific things on specific dates, because we have records. It takes rigorous imagination to grasp that the same is true of everything that has ever happened to humans, including early calamities that we don’t have a record of. There was always some event that happened on some particular day that involved some particular people and that led to loss of trust in life. That loss of trust in life is the deepest seed of what we are still living today, thousands of generations later: the shift from living within life to exiting, separating from, and controlling life. Calling it patriarchy is because at some point that cycle of control and trauma began being attached to fathering, at which point women had to be controlled. And that painful twist to it is well outside the scope of this particular post. What’s devastatingly central to what I am focusing on here is that controlling life means restricting movement through coercion and suppressing wanting through shaming.

This is where mulberry trees and then babies come into this story.

We can’t shame trees

When we came to this town, the mulberries had already been cut. So much so, that they were unrecognizable to my eyes, and I didn’t know I was looking at mulberries. For the winter months, I only knew that the trees I was passing by every day on my walk by the sea had been subjected to immense casual violence, like other plants here and elsewhere. The image I selected below, although already after leaves and fruits started appearing, still shows the extent of wounding to the trees. The center of the image looks to me like one massive scar.

I have since read about pruning mulberries, with repeated warnings not to cut branches that are wider than 5 cm (2 inches), because they don’t heal well. Who, then, decides to cut them so intensively? And why would anyone do that? This isn’t a rhetorical question. I really don’t understand, both at the level of not getting the intention and at the level of the impact on a living being. Even knowing that this is a fancy tourist town I don’t understand why anyone would think that this could be more pleasing to the eye than the flowing images of a healthy mulberry tree that I was seeing everywhere in Ankara, Turkey, during the months of living there in 2023. And, regardless, what has happened to us that we can be so cavalier about cutting, trimming, clipping, and in any way controlling the movement of fellow creatures without even noticing it?

Then came the spring, and I started seeing fruits and leaves popping up on bare trunks and pointing upwards instead of hanging from branches and covered by leaves. That’s when I understood more viscerally than ever before the raw tenacity of life. All winter long, the living spirit of the tree gathers up energy, waiting without knowing what “waiting” means until the moment comes to find new pathways for fruit, leaves, and new branches to greet the warming days. And if the configuration of branches that is what the tree would naturally unfold within is not there, the force of life will lead to distorted versions of a mulberry tree, seeking to continue life, with all the might they have, despite whatever conditions they are put under. They can be coerced and prevented from growing how they want, and they will never stop wanting and trying.

Only shaming can stop any living being from wanting.

Shaming babies by making belonging conditional

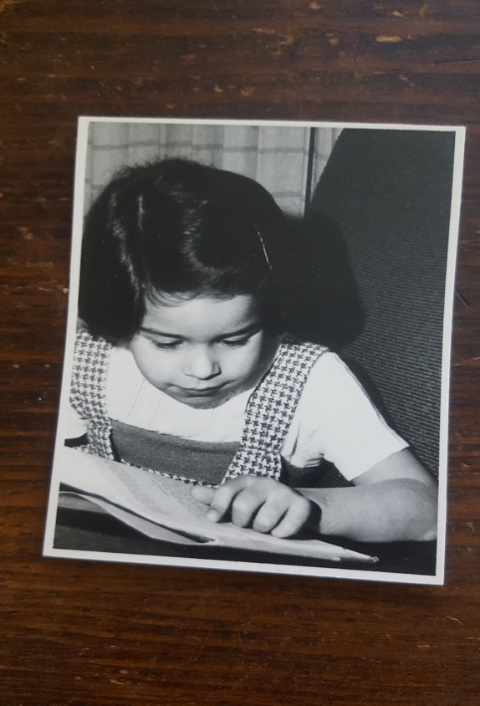

My mother kept a diary about me when I was young. Most of the entries are from when I was five and six years old, and there are some few entries from the first weeks and months, some of which I am reproducing below with commentary to point to what I think of as shaming:

Here’s what she wrote only twenty-eight hours after I was born: “They brought you to me for a 10 am meal. …. You were fast asleep and I couldn’t feed you. The nurse spanked you on the butt until you woke up crying and started learning the craft of suckling.”

This early in life, the message is already clear: my own needs, rhythm, and what I want are made secondary to the needs and rhythms of the adults. This is still “only” coercion, without shaming.

And three days later, only four days into my life, the seed of making the wanting itself problematic is already present: “What a night you made for us. On grandmother’s advice (and I decided to follow her advice), I responded to your crying and fed you. So you ate almost every hour and a half. This has got to stop.”

Here, for a moment, she is actually orienting to what I clearly needed (why else would I cry?), and in the same breath is condemning it.

And, at four months old: “It’s been a few days that you have been a very bad girl. After dinner you start crying a lot. Friday night we had guests, but you were not considerate at all, and stayed up until 3 am.”

It’s rare, I believe, to have such a direct look at the thinking that goes into how modern humans orient to children. I don’t believe my mother was exceptional in any way. Everyone I have asked knows exactly what counts as a good or bad baby. The idea that a four-month-old, fresh and vibrant human being, could be “bad” or “not considerate” is wrenching for me. That the goal would be a “good” and “considerate” baby, and that this would mean fully orienting to the needs and rhythms of the adults, is scary. It’s not about it having happened to me, because I managed to resist this.

Here’s an entry from when I was two years and seven months which shows exactly that: “You are remarkably independent, and it’s scary what a strong character you have. It’s very hard to get you to change your mind.” As a 68-year-old, I take immense pleasure in knowing that I managed to retain my wanting.

Tragically, most of us succumb to the immense pressure and choose being “good,” whatever that means in our environments. This is how we are inducted into the existing social order.

Understanding why we do this takes us into a deep journey into making sense of patriarchal socialization, which leans heavily on coercion and shaming. This is a big piece of what my sister Arnina has dedicated years to investigating while working with hundreds of people from multiple cultures. What she discovered, and which we wrote about in an article called “Parenting without Obedience,” is the presence of an unspoken, implicit, raw deal that is the essence of patriarchal socialization. We are told that in order to belong, we must give up our freedom. Just like trees, no amount of coercion by itself would be enough for that. Coercion is enough to severely restrict our movement, both as babies and as adults (just think about immigration laws), and not to eliminate it. For as a long as we hold on to what we want, we will never fully give up our freedom. Like the mulberry trees, we may distort and reshape our movement, and, still, within the confines of what is possible, we will find a way. I almost always have.

Only shaming can induce us to give up on knowing what we want, because it attacks our belonging directly. It’s not for nothing that the old Jewish sages said that humiliating someone in public is tantamount to killing them. Our existence, as social beings, is entirely wrapped up in belonging to a group, which is why shame is so unbearable to experience and stops us on our tracks, eventually causing us to join with others in believing there is something wrong with who we are. This is how we internalize it all. And once we do, far less coercion is needed, because we comply seemingly voluntarily. The distortions we have needed to adopt in order to survive at all then appear to us to be who we are. We forget something else is possible. And, eventually, we coerce and shame the babies that come here through us.

I want to be like the mulberry trees.

Image credits

Images created by and used with permission from Miki Kashtan, excepted:

Mulberry tree on the beach, Calella de Palafrugell, image created by and used with permission from Luca Incorvaia

Mulberry tree in Ankara, image created by and used with permission from Alper Süzer